Masterpieces from the Pijpenkabinet

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Topstukken uit het Pijpenkabinet

Publication Year:

2010

Publisher:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description:

Web presentation illustrating and discussing fifty masterpieces from the Pijpenkabinet collection in Amsterdam

Preface

With its 27,500 objects, the Pijpenkabinet Foundation manages an extensive collection of smoking equipment and related objects. In this web presentation, a choice of over fifty objects will be highlighted and explained in more detail. The selection is representative of the wide variation within the collection. What binds the objects is that they are masterpieces, but in different respects. Often they are special pieces because of their historical value, sometimes they are visitors favourites, in other cases objects with a remarkable beauty or a bizarre appearance. The story behind the object can also play a role in the choice. All these museum objects form a link in the history of smoking, a worldwide history that has an infinite number of aspects. Scroll down and read more about the unexpected aspects of the global smoking culture.

Those who want to orient themselves on the best pieces from the Pijpenkabinet collection can use the link below to make a wider selection. Then more than five hundred objects emerge that are qualified as the most characteristic by the curator. However, these are not described as the fifty toppers and explained with their own story. They are taken directly from the collection database. Of course, this choice is also subjective. The collection of the Pijpenkabinet contains numerous remarkable objects that would qualify as well for inclusion in that list. In addition, the top five hundred even contains relatively ordinary objects that are of great importance for the history of the pipe, but do not always have a high attraction value.

Prehistoric

Mythological animal

The primal shape of the tobacco pipe does not show the pipe bowl as we know it, with a hollow stem, but has the shape of a tube. This so-called tubular extends from the mouthpiece to the other end in a kind of pipe bowl or furnace. Here the tobacco can be packed. The tubular remains a simple but popular shape for a smoking pipe for centuries.

Several such tubular pipes are known from Ecuador, which are occasionally embellished in a beautiful and original way by figuration. This happened mainly at the Jama-Coaque in the Manabi region. This tribe did not have the wish to make a comfortable stemmed pipe with an upright pipe bowl. They were used to the tubular shape, which was in line with the attitude and rite of smoking. However, there was great interest in decorating the tubular pipe by making a figural shape. With a successful product, the artistic decoration completely overshadows the pipe shape.

The illustrated pipe is a fine example. The simple tubular shape is completely hidden in a lying mythological animal, the representation of a wolf or lion. The technique of manufacturing is remarkable. The basic shape of the pipe is made by hand, the tail of the animal being the mouthpiece of the pipe. The legs on both sides of the stem are hand-sculpted. Subsequently, a mask-like head, applied to the upper side, was produced with a simple printing mould. Finally, details such as earrings and a tongue were hand formed and added by hand.

The representation is particularly successful, the animal is in a defensive position and the head is surrounded by a broad geometric headdress. A triangular flared tongue and comma-shaped earrings complete the figure. Characteristic of the tubular pipe is of course the fact that the bowl is located at the front and is not positioned at an angle of ninety degrees to the stem. In the latter case, it would end up behind the head of the animal, as is usual with the standard pipe. After the product was baked, some details were probably polychrome, so that a colourful end result was obtained. These colours has faded in the course of more than two millennia.

Such objects from the Jama-Coaque culture date from 550 BC. This specimen will date from the fifth or fourth century. These are rare archaeological examples from the prehistory of smoking that prove with their artistic element that tobacco use evoked inspiration already in the earliest phase.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 13.513

The mescaline cactus as inspiration

The most characteristic pre-Columbian pipe has a bowl shape that is inspired by nature. For the pipe bowl the mescaline cactus was copied: a spherical cactus with vertical cooling fins. The mescaline cactus is a common plant in those areas, often with an aerial root that is depicted in the pipe stem. When the cactus blooms, one large flower appears in the crown, initially as a cylindrical bud but spreading out to a calyx in full bloom. In smoking pipes according to the example of this cactus, the different stages of flowering are shown, with full bloom being the most common. Rare is the representation of a cactus without a flower. The pipe shown is particularly special because the flower is still shown in the bud, which rises from the cactus like a cylindrical box.

In the stem of the pipe, the maker depicted an aerial root and thus gave an extra realistic dimension to his creation. Referring to the root structure, the stems are often provided with a repetitive pattern of imprinted stripes. The two legs at the bottom of the bowl are for the pipe to be put down, typical for the use in Mexico. Cactus pipes are finished in different ways. Sometimes the pipe has the colour of the baking from greyish to terracotta red but usually with slip colour accents. With this pipe, the greyish colour of the ceramic stands out against the striking effect through partial polishing. The mouthpiece is appropriately accentuated with white engobe, which is also polished.

The mescaline cactus itself was used as a stimulant by the Indian tribes. At religious festivals people ate dried pieces, called peyotl or pellote. They provided hour-long nebulisation and associated colour visions. Reason to portray this cactus in a pipe is certainly not in the need to process nature in utensils, that is not typical of that culture. Rather, a relationship has been established between the hallucinogenic effect of the cactus and the disfunctioning effect of the nicotine in the tobacco. The extent to which the dried pieces of cactus were also smoked is unknown.

It remains an unanswerable question whether the makers of the cactus pipes have known the function of the cooling fins or have merely copied the natural shape of their beloved cactus. In any case, the ribs provide surface enlargement and thus better heat dissipation to the environment. As a result, the temperature of the burning tobacco decreases so that cooler smoke is released that tastes milder. However, the fairly massive design of most cactus pipes negates this cooling effect to a certain extend.

Literature: Don Duco, A pipe to nature, design aspects in pre-Columbian tobacco pipes, Amsterdam, 1995

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 9.622

The primeval pipe in full

It is certain that the European clay pipe has been developed from the native American tobacco pipe. Yet the number of striking similarities between pipes from both cultures is not very large. Many pre-Columbian pipes have a free design in addition to a much larger size. The pipes from Central America were in fact formed by hand and could therefore have any desired appearance with a funnel-shaped or rounded bowl, either in a smooth design or with decorations.

The pre-Columbian pipe depicted here shows the greatest resemblance to the pipe shape that became popular in Europe. It is a simple pipe made of grey ceramic. After modelling the surface is provided with a red slip or engobe which has subsequently been smoothed. A more or less regular pattern of stripes is obtained by brushing along the leather dry clay with a hard polishing tool. After baking this ensured a lasting shine.

As expected, the dimensions of the American pipe are completely different from those of the early European counterparts. For example, the bowl has a height of almost eight centimetres and is therefore more than three times higher than that of the Dutch clay pipes from the first generation. The stem, on the other hand, is not correspondingly longer, it only measures 11.5 centimetres. Because it is thick at the beginning and tapers thinly towards the mouthpiece, the diminishing of the diameter of the stem is much stronger than we see in the Dutch pipes. Despite these differences, the appearance of this American pipe with its double conical bowl, flattened underside and short, straight stem is in line with the original shape of the European tobacco pipe.

We are uncertain about the age of this pipe. It must date between 500 and 1500. For decades this object was part of the well-known SEITA collection, the museum of the French tobacco monopoly. That museum acquired the pipe from Eugène Jance's famous collection. Jance lived in Marseille and collected everything related to tobacco and smoking for decades. Unfortunately, insufficient attention was paid to documenting the material during the transfer of that collection. Eventually, Jance's notes got lost. With it, the object information about the date, location and circumstance of excavating, including the name of the person who found this item, was lost for posterity.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 19.923

Archaeological

A pipe like a horn

The Dutch clay pipe is a typical serial article. It is made in large numbers in a press mould and is therefore uniform in shape. Only during the finishing some additional actions could increase the quality. In rare cases does the pipe maker feels the need to come up with something original and therefor interrupts the serial production. Then he moulds a special object out of a piece of pipe clay, with or without pre-formed parts from a mould. An example of this is the pipe shown here in the form of a bent horn.

Although this pipe is largely made by hand, it is really a product by a regular pipe maker. The bowl was pressed in a standard two-piece press mould that was only available at the pipe makers’ workshop. Subsequently, a much thicker stem was made on this pipe bowl, which was connected to the largest diameter of the pipe bowl and was strongly tapering towards the end. This probably happened on the wire, the pin that was normally used to make the smoke channel. After the surface was smoothed and the iron wire removed, the clay roll was bent in a large upward bend with an opposite bend at the mouthpiece. A stamped decoration, consisting of three batches of lilies in diamonds, is arranged as a finish, each group separated by three concentric rings of millings.

Such pipes can be made anywhere in the Netherlands, although the tools point to manufacture in the city of Gouda. Firstly, the press mould used has the so-called dikkop size, a pipe shape that was launched in Gouda in the 1640s and has only been popular for a short time. In addition, the use of a specific milling stamp and the stamp to make the diamond shape filled with a lily are characteristic for the city of Gouda pipes. This version of the lily motif is in Gouda in use between 1645 and 1650, after which it changes its size and appearance. The date of the stamp corresponds to the production period of the press mould used.

You would expect that such a hand-modelled pipe is unique, but that does not seem to be the case. More often fragments of such pipes were found, but because they were small pieces, we remained uncertain about the shape of the complete pipe. This discovery from the city centre of Leiden means that we now know what a complete pipe has looked like. The way of making indicates that it cannot be unique, rather a product made in a small series. The method of manufacture is too perfect and above all too sophisticated to be a piece on its own. Although the bent horn as a pipe has been a temporary phenomenon and only became known among a small group of smokers, the spread is still wider than one would expect. Most surprising, however, is that fragments have been excavated in Virginia from a nearly identical curved horn pipe, made locally but unmistakably with an example of such a Gouda specimen.

Literature: Don Duco, Thoughts around a mysterious find complex, 1995.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 9.601

An exotic from the polder

Most of the pipes found in the soil are ordinary pipes in common shape, sold by the thousands, generally smoked and then thrown away. It is only rarely that an alternative smoking instrument is found, coming from a smoker who liked to show off with something special. Such a remarkable discovery was made in 2001 in Schermerhorn near Alkmaar. From an ditch fill a most exotic pipe emerged, which apparently came to the province of North Holland as a souvenir.

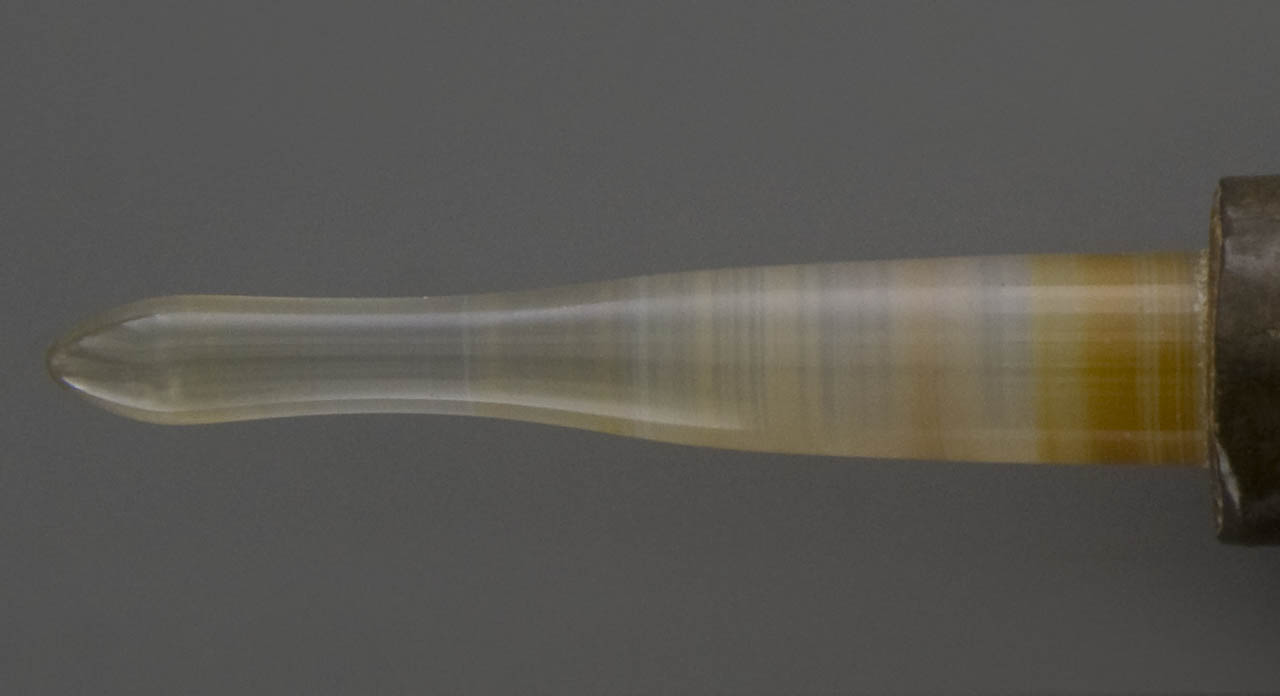

It is a so-called stub stemmed pipe, a pipe with a truncated stem to which a separate stem was attached. The pipe bowl is made of a relatively soft baked light grey clay. As a result, the pipe guarantees an optimal absorption of the tar and nicotine juices released during smoking, resulting in dry and therefore tasteful smoking. For the Dutch smoker the bowl is generous in size, the local pipes were certainly three times smaller. This pipe bowl has a cylindrical shape with a slight reinforcement at the opening. A dish-shaped widening has been applied at the base, which turns into a semi-circular underside. A kind of rat tail is visible as marking of the underside and as a prelude to the stem. The pipe is provided with a rising stem that is reinforced with a cuff band with a semi-circular profile. Although the stem ends with a cuff, it still runs through the same diameter. All these characteristics indicate an origin in the Ottoman Empire.

Completely opposite to the Dutch clay pipe, this product is not printed in a two-part mould but is made on a potter’s wheel. Bowl and stem are turned separately and then glued together with some moist clay, the so-called rat tail functions as reinforcement. Then the seams were carefully smoothed out. Finally, a decoration was stamped that made the last traces of gluing the two parts invisible. During the stamping of the decoration, a repetitive pattern was created, separated by ropes and chain lines. How seriously this decorating was done is proven by the fact that 120 individual imprints have been made. It is striking that the four different stamps that were used alternatively differ so little in detail that the effect with one and the same stamp was hardly any less.

In addition to the fact that the pipe bowl still is in perfect condition, it is unique to this find that the original stem was also found. Against everyone's expectations, it is not a stem made of reed, wood or bone, but in lead. This might be a local replacement for a previous one that was blocked or broken. Especially the stem end is remarkable: this is cut out so that it gives the impression of being copied from the original twisted stem end. By the way, lead is not a suitable material for a pipe stem, it gives off taste and does not absorb moisture. Fortunately, the latter, negative factor is more than compensated by the porous bowl, so that the pipe will still have smoked pleasantly.

The fact that such an exotic pipe was found in the rural Schermerhorn is unexpected but not completely strange. The population lived there from fishing and shipping. It is possible that one of them signed on a ship heading for Gibraltar and ended up in the eastern Mediterranean. For example, this pipe made at a distance of at least two thousand kilometres can end up as a travel souvenir in Schermerhorn. In view of the finding conditions, this must have been between 1665 and 1685. At home, the smoker was in any case assured of all attention for his exotic smoking equipment.

Literature: Don Duco, An exotic pipe from Schermerhorn, Amsterdam, 2003

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 16.824

The Stadtholder as party pipe

Over the centuries the House of Orange has always been a source of inspiration for making special pipes. Not surprisingly, the House of Orange was widely supported and a pipe devoted to a happy or memorable event could count on good sale. This topic has already been discussed extensively in the publication De tabakpijp als Oranjepropaganda (The tobacco pipe as propaganda for the House of Orange) and is illustrated with dozens of commemorative pipes. A specimen that does not appear in that book is this special tobacco pipe. When the Orange book came out it was still uncertain who was depicted in the pipe, especially because at that time only fragments were known.

It is a large-sized tobacco pipe that differs in every respect from what was regular in that period, the end of the seventeenth century. With a height of 9.5 centimetres and a diameter of over 5, this pipe is many times larger than the standard bowl size at the time. The standard pipe bowl was at that time about four centimetres high with a diameter of less than two. Figural pipes from that time are also an exception, but in this format it is certainly an exceptional showpiece.

The pipe represents Stadtholder William IIIrd, by his marriage raised to King of England in the year 1689. With his hair and bow he is dressed to the fashion of his time. Although more statesmen, high officers and naval heroes were dressed in this way, this is unmistakably the Stadtholder-King, as he is known from formal portraits and the numerous prints derived from them. The date of this pipe is therefore between 1690 and 1700, possibly several years later.

The prototype for this portrait pipe can be seen as being modelled out of hand and the result is little sculptural. The face is rather flat, the eyes, nose and mouth not very pronounced. The face is surrounded by a wig made up of small semi-spheres and only at the back the hair is shown in straight lines that form an unexpected contrast with the curls. All in all not a very naturalistic representation. At the transition from the bowl to the stem you can see a scarf, the pleated end of which hangs over the stem. A bow to the fashion of the days around 1700. On the stem the image is continued with a few clothing buttons, an little ring round the stem indicates the waist of the sitter. The plan to create a full-plastic, three-dimensional portrait head is only moderately successful.

Special about this pipe is the method of manufacture. Clay pipes are pressed into a two-part metal mould, but certainly no metal is used for this specimen, but rather ceramics, to be concluded by the blurry impression. The giant mould did not close in the usual way with a left and a right half, but the seam runs along both sides of the pipe bowl. The mould box therefore consists of a lower and an upper half, which is ingeniously conceived in itself. Partly because of this, the pipe makers' mark could be applied in the mould and did not have to be printed separately.

How large the circulation of this giant pipe has been can only be guessed. It is certain that it was a serial article that was made in plural. A ceramic mould, however, wears quickly of, so after a few hundred pieces the sharpness has decreased. In the meantime fragments from the same printing mould have been known from various find spots in the Netherlands.

Several specimens of this pipe are provided with a moulded crown, which gives the pipe bowl a height of twelve centimetres. Also with this pipe, the onset of it is still visible, the crown itself is apparently broken off and lost. When the printing mould had lost its sharpness, the pipe maker felt the need to compensate the wear with additional modelling work. The worn form seam was obscured by suggesting a wig here, which was provided with simple circular prints to resemble pipe curls. It is hardly a beautification. The modelling work on the pipe does indicate the atmosphere of production, which was certainly serial, but still remained limited in numbers. We can wonder if the wig was an attempt to depict a portrait of the French king Louis XIV, instead of approaching the Stadtholder. The Sun King had a very similar appearance but a much more impressive wig.

The initials HIS on the heel refer to the maker, a man named Hendrick Jansz. Sprot from Gouda. Because of his second marriage in 1687, Sprot ends up in the pipe industry via his father-in-law. He learns the trade and finishes his master's proof in 1690. Presumably he worked in the company of his father in law. A few years later Hendrick will take over this workshop and his mark the tea pot. His own mark, the initial mark HIS, does appear in the guild administration but is rarely found on pipes. The pipe making workshop of his father-in-law was sufficiently lucrative to provide a good existence. Nevertheless, Sprot has been looking for new sales opportunities.

Inevitably, such a special pipe raises questions. Technically about what the mould looked like. Also how large the production numbers have been and whether this pipe was made incidentally or at the occasion of some special event. In addition, we can speculate about the use. The pipe can be used as a smoking pipe, but can the smoker afford so much tobacco? In view of the smoke traces in our example, this pipe was smoked at least once. Of course, the pipe can also be used as a hang-out sign for a pipe store. Some fragments have been pierced at the heel, so that the pipe could be easily hung. With such a big pipe you make more effective advertising than with a standard product and in addition you confess your sympathy for the House of Orange. In a special case, this object could also have circulated as a drinking utensil in the pub, for example when drinking an orange liquor.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 20,250

Pipes made of clay

A mysterious standard Gouda pipe

From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the name maatpijp, standard pipe is a fixed concept. It is a long clay pipe from Gouda with a straight stem. Initially these pipes were 17 thumb or inches long, then 19 inches to end up at 21 inches or more than fifty centimetres. Pipes with this stem length and a standard oval bowl shape fit into an industry with high product standardization and fierce competition. The maatpijp has been a common article for two centuries. Everyone knew them and wanted to smoke them. The pipe tasted pleasant because of the long stem that cooled the smoke well.

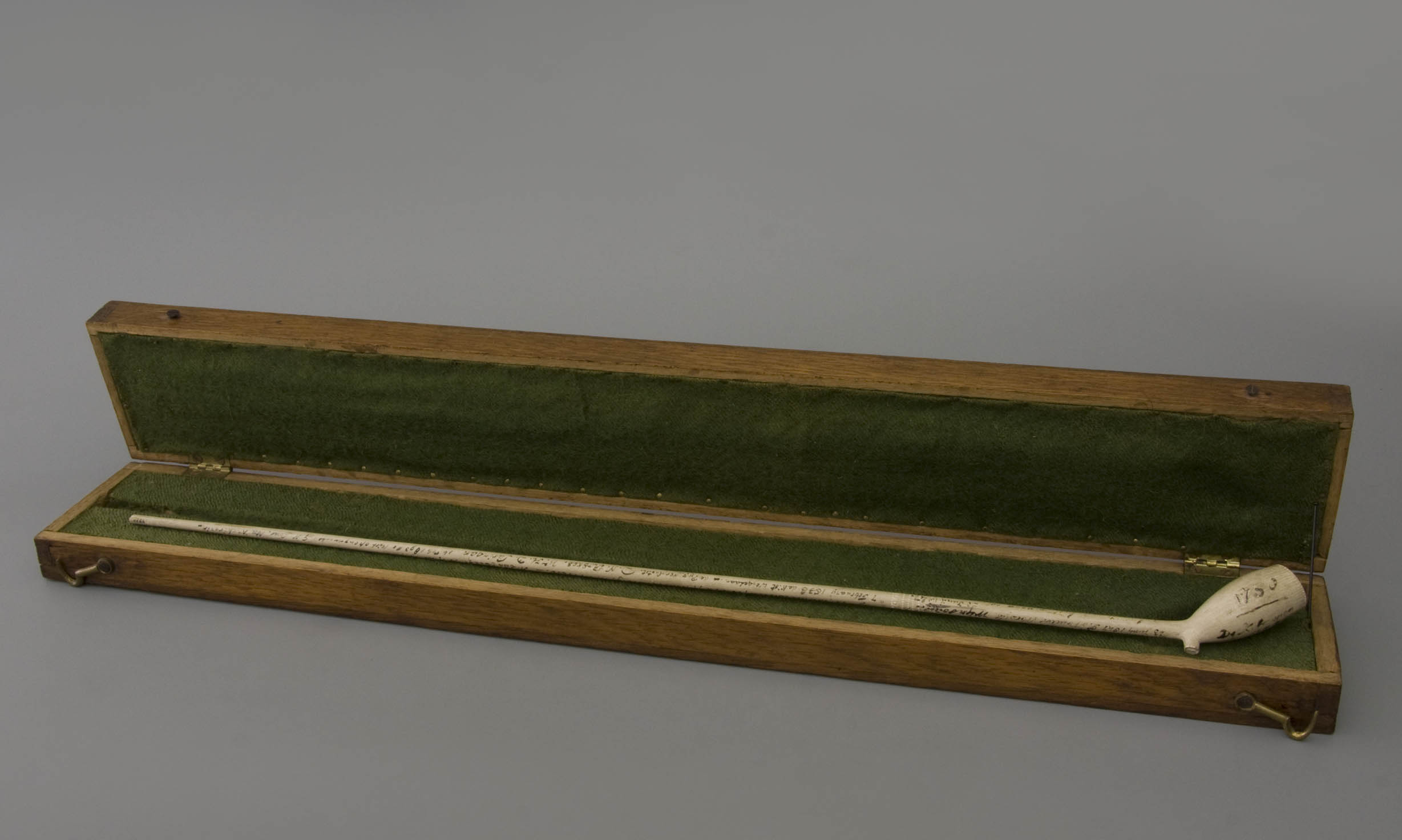

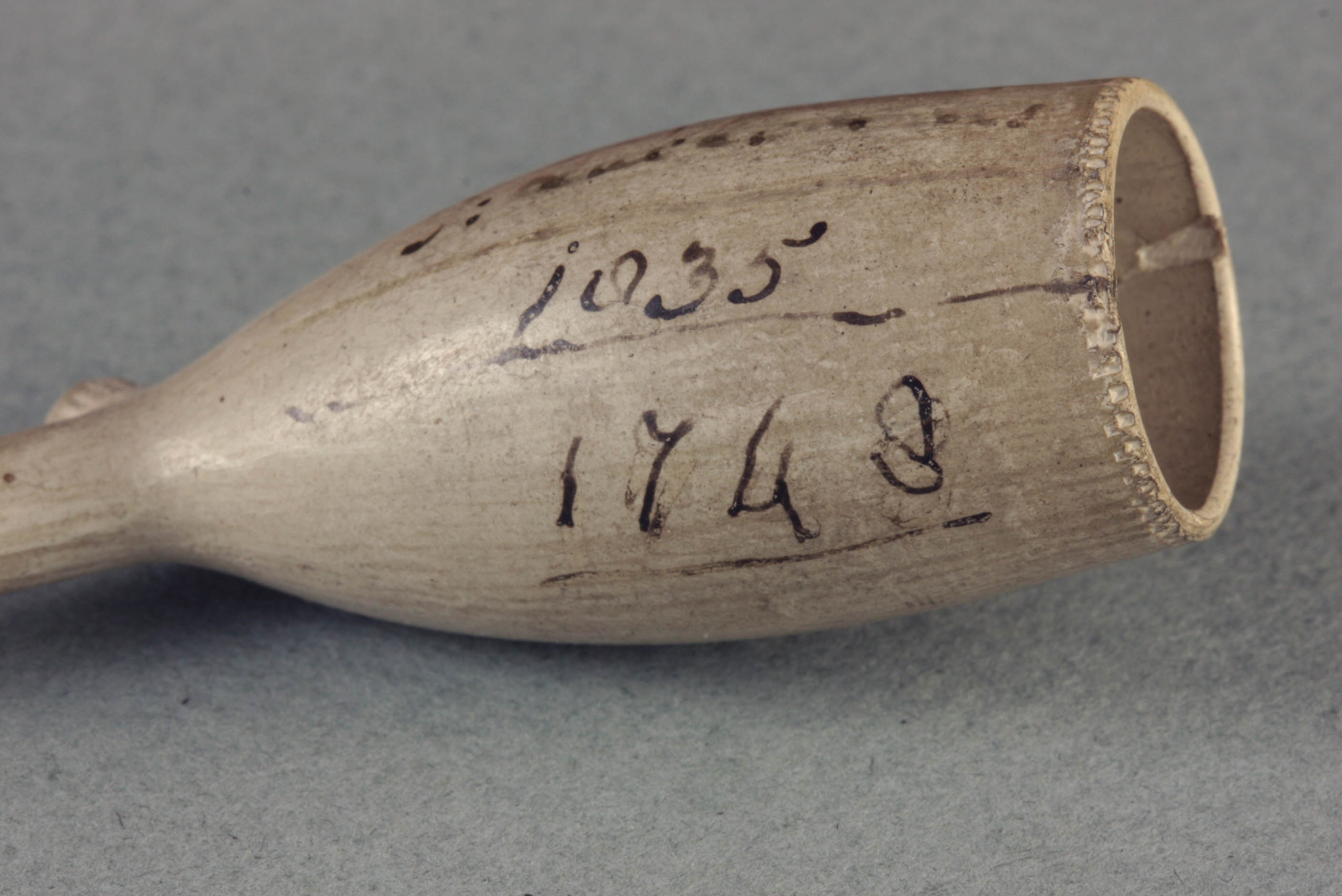

There was always a fresh supply of the maatpijp and apparently nothing changed on the product. Therefore, no-one has ever had a reason to preserve such a pipe as a time-bound object. The article was always repurchased and used copies were smoked without mercy until the end. So, the more rare it is when by chance such an ordinary pipe has been preserved. That is the case with the clay pipe depicted here, which is neatly protected in a box for breakage and thus survived the centuries.

The elongated oak storage box closes with two brass hooks and in the interior is hollowed out in order to provide a safe space for the pipe to comfortably rest on a green cloth. This way the clay pipe remained intact and eventually won the predicate “oldest preserved maatpijp in the world”. Thanks to the marks, we know the origin. On the stem is stamped "I: WOERLE" and "IN GOUDA" which refers to the Gouda pipe maker Jan Woerlee, active from 1736 to 1777.

Special about this pipe is that the bowl and stem show inscriptions. It appears that this pipe was in use by the regents of the poorhouse in Leiden. The series of 23 different names on the stem corresponds with the regents of this alms house in different years. It seems that the pipe has served as a ceremonial object. When the gentlemen regents met, they wrote their names and the year on the bowl or on the stem of the pipe in ink. That use started in 1748 and as continued until the last time in 1893.

Unfortunately, we can only guess at the circumstances of this wondrous use. Especially a few in-betweens give opportunity for further speculation. For example, from the inscription of 7 February 1838: "the box removed, the pipe moved" or that of 30 March 1844 "the box has been opened and the pipe has been moved". A remarkable text is also: "Congratulations to the further readers" even though the word smokers had been better placed for a pipe here.

Mentioning the box does not seem to refer to the wooden box of the pipe itself, but rather to a larger chest in which the pipe with box and all was kept. Did they mean the cash box of the poorhouse in which the assets were kept? Then the names should be that of the treasurers. Strange is that the box was only opened once every few years, sometimes even at great intervals. Should the valuable contents of the chest not be inspected more often? For the time being it seems that this riddle is not solved and that is the intriguing added value of this oldest preserved maatpijp. In any case, one thing is certain: no-one has ever enjoyed the smoking of this pipe, tobacco has never burned in this pipe, so the bowl is still virgin white inside.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 4.970

The cigar holder by Andries Van Houten

In the second half of the eighteenth century smoking cigars became known, initially with thin cigars that were rolled completely by hand. The taste is a new sensation for the smoker. Until now people were used to a combination of American tobacco cut and mixed with local leaves from Gelderland or Alsace, the cigarillo made people get acquainted with a heavier and fuller taste. An important change was also the appearance for the smoker, who became more free, more casual. The cigar could be smoked with more nonchalance while at the same time it stood for greater luxury and a striking way of tobacco consumption.

In the Netherlands, cigar makers quickly started a production in imitating the Caribbean cigars. The Dutch thrift led to the admixture of cheaper domestic tobacco with the positive result that the cigar was also affordable for the middle class. In order to emphasize the sophisticated way of smoking, cigar pipes appear soon on the market: simple straight tubular clay pipes in which the cigar is placed. They are called cigar pin.

The pipe makers in Gouda respond to this new smoking habit and make simple cigar holders. In line with the Gouda industry, they are finished just as beautifully as the Gouda tobacco pipe. After pressing in a mould and cleaning the mould seams, the surface is polished with agate to give the pipe a nice shiny appearance. In this way they fit the luxurious cigar with its dark matt appearance that contrasts beautifully with these bright white pipes.

One Gouda pipe manufacturer, however, designs a cigar holder that witnesses to a special luxury and extravagance. This pipe is not short but long and measures 21.5 centimetres. Moreover, this pipe is not smooth polished but decorated over the full length with an embossed decoration applied in the press mould. The pattern of this decoration is based on the usual decoration on the stems of the long Gouda pipes: a swinging tendril with leaves and flowers, interspersed with some animals such as a sitting pigeon on top and between the branches two minute flying birds.

Because an explicit pipe bowl is missing in this long, tubular pipe, the bowl part remains somewhat unobtrusive even if it is marked in the decoration. On the bowl part the manufacturer placed his mark crowned 73 between concentric rings with some foliage. On the reverse he placed the coat of arms of Gouda in a wreath of thorns as a sign for the place of origin. The makers’ pride is shown also in the addition of his name "A.VAN HOUTE" and "IN GOUDA". It is remarkable that this exceptional pipe design is based on the well-known Gouda decoration patterns; apparently, both Van Houten and the mould maker lacked the originality to think of a completely new decoration. Even the manner of finishing testifies to a certain rigidity. For example, a milling around the bowl opening has been made, in this case actually a superfluous luxury.

The Van Houten House was a totally atypical workshop. Where most companies in Gouda focused on the standard goods and mainly specialized in a certain length and quality, Van Houten mainly produced exceptional models. They sold these pipes as an assortment supplement to the standard products Van Houten bought from other workshops. This wonderful cigar pin fits perfectly in Van Houten's varied range.

That this fragile cigar pipe survived time is an absolute miracle. The production date will be between 1760 and 1790. The cigar holder has served as a regular pipe for years, the smoke traces testify to this. After that, the pipe will be stored as a curiosity. Eventually the object landed in Ruhla where it was mounted to German standard with a meerschaum bowl insert and an amber mouthpiece. Thanks to the fact that a protective case was added at the same time, the pipe was further safeguarded against breakage. In this way he could easily survive another century undamaged.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 18.959

A figural pipe with a lid

In the 1830s a new craze developed in the pipe industry. After the fashion of the figural pipe had become a great success and the pipe was the conversation piece for the smoker, a following phenomenon occurred: the lifelike portrait head who could smoke himself! Different manufacturers bring such pipes more or less simultaneously on the market. These are heads with a lid that obscures the annoying circular cut of the bowl opening and makes the pipe into a full sculpture. Gradually that lid was provided with an added joke, which we see in the pipe shown here.

The pipe bowl shows a man's head with open mouth, a face that seems to peek between ears of corn and flowers. Undoubtedly the smoker knew exactly who was being portrayed at the time, but the meaning was lost over time. Incidentally, the face is beautifully modelled and striking is the well-formed opened mouth. With its round facial expression, the face forms a beautiful contrast with the sharp forms of the flora. The lid on the pipe bowl is part of the image: it is the hat of the person, as it were, but there is something unusual about that lid. It is not equipped with air intakes as usual to draw the pipe, but it is completely closed and that is the trick. The manufacturer introduced a smoke tube in the bowl wall from the forehead downwards up to the mouth of the depicted. The mouth therefore acts as an air inlet. This system made it possible that you can simply smoke out of the pipe.

After you filled and lit the pipe, you put the lid back on the pipe bowl. If you do not smoke but blow gently into the pipe stem, the smoke starts to come out of the mouth spontaneously. And what entertainment will that have given!

The maker is Crétal & Gallard from Rennes, an important factory we know little about. Thanks to the signature on the stem of the pipe we can make the attribution. The stem shows the shape number 462 with the addition that the design is patented, although without a government guarantee as the inscription says. The patenting of inventions by factories was common at that time. In February 1856, Crétal & Gallard received a fifteen-year license for "une pipe à trou d'air renversé" as the system described here was explained. Although it seems to be a unique discovery of the Rennes factory, that may not be the case. In 1858 a patent for a similar system for Belgium was obtained by Wingender in Chokier near Liège. It is almost certain that pipes with this system were already being used extensively in France and Germany. In that respect, the patent is not always indicative for the moment of production. The copy shown here must have been made between 1856 and 1860. In later times this model was made without the ingenious system.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 9.372

Braided pipes for the queen

For the residents of Gouda, 24 April 1897 was a special day. On that date, Queen Regent Emma and her daughter Princess Wilhelmina would visit the city of Gouda. The program included a visit to the candle factory and a look at the Saint John Church for the famous stained glass windows, next to a visit to a pipe factory. The honour was given to the firm P. Goedewaagen & Zoon, not surprising because the firm's owner, Pieter Goedewaagen, was member of the municipal board of Gouda.

The local newspaper Goudsche Courant gives an impression of the preparations for the Royal visit one day before the event. It turns out that at Goedewaagen the entire factory has been cleaned, an impossible task in a ceramic factory full of clay dust. At the entrance of the factory even a sort of boudoir was arranged to receive the Queen Mother and her daughter in a dignified way. On the way to this reception hall they built a canopy consisting entirely of long stemmed Gouda pipes.

A day later we read an extensive report in the local newspaper. The queens have then seen the longest kind of pipes being made by the most skilled master pipe makers. The other workers were watching along the wall dressed in their Sunday suit. This longest type of pipe is decorated with the coat of arms of the House Hannover, in fact the English royal family, but for the occasion the pipes were renamed pipes with the arms of Stadtholder-King William III. A dozen of the long clay pipes made in presence of the two royals were combined during the visit to an exceptional plait. Around it are some other figures that make the whole into an art work of clay pipes.

After the visit the braided pipes were baked and were given a place in the reception room of the factory as a reminder of the royal visit. The fact that the manufacturer was very honoured is also apparent from a silk-bound guest book, in which the two queens have written their names with the addition of the date of their visit. On the cover of this beautiful cahier, the Dutch coat of arms appears in gold. That book was since then shown at the reception of important relations.

Until the 1970s, the artwork of pipes hung in the Koninklijke Goedewaagen factory. Initially on the Raam, from 1909 on the Nieuwe Vaart in a brand new factory building. In the 1950s the piece moved from the showroom to the boardroom. At that time it was incorporated in a modern wooden panelling. It was not dismantled until 1974 and two years later this special object was transferred to the Pijpenkabinet Foundation. The factory management found a museum destination more appropriate. The original frame has been restored since then and the object could be exhibited in its original way. It is now in full glory as one of the most special clay pipes in the main room of the Pijpenkabinet in Amsterdam.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 10.831

Ceramic smoking pipes

A dedicated Staffordshire pipe

The term Staffordshire pottery is a collective name for ceramics from the English region of Staffordshire. In six places close to each other, of which Hanley and Stoke are the best known, earthenware has been made with a great variety for centuries. In the narrow sense, the term Staffordshire also stands for folk ceramics that are often formed in figures and provided with coloured glaze. The pipe depicted here satisfies all aspects of this definition.

The ceramic tradition in Staffordshire developed so well thanks to the fine plastic clay that was locally extracted and which produced a beautiful white baking product. In the course of time, the potters gained ample experience in working with colourful under glaze. In addition, the figuration of the products became a passion in itself. Tobacco pipes are included in the supply between 1790 and 1840. The most famous family that made this ware was Pratt, which is why the Englishman often speaks of Prattware, although the word Staffordshire remains more accurate.

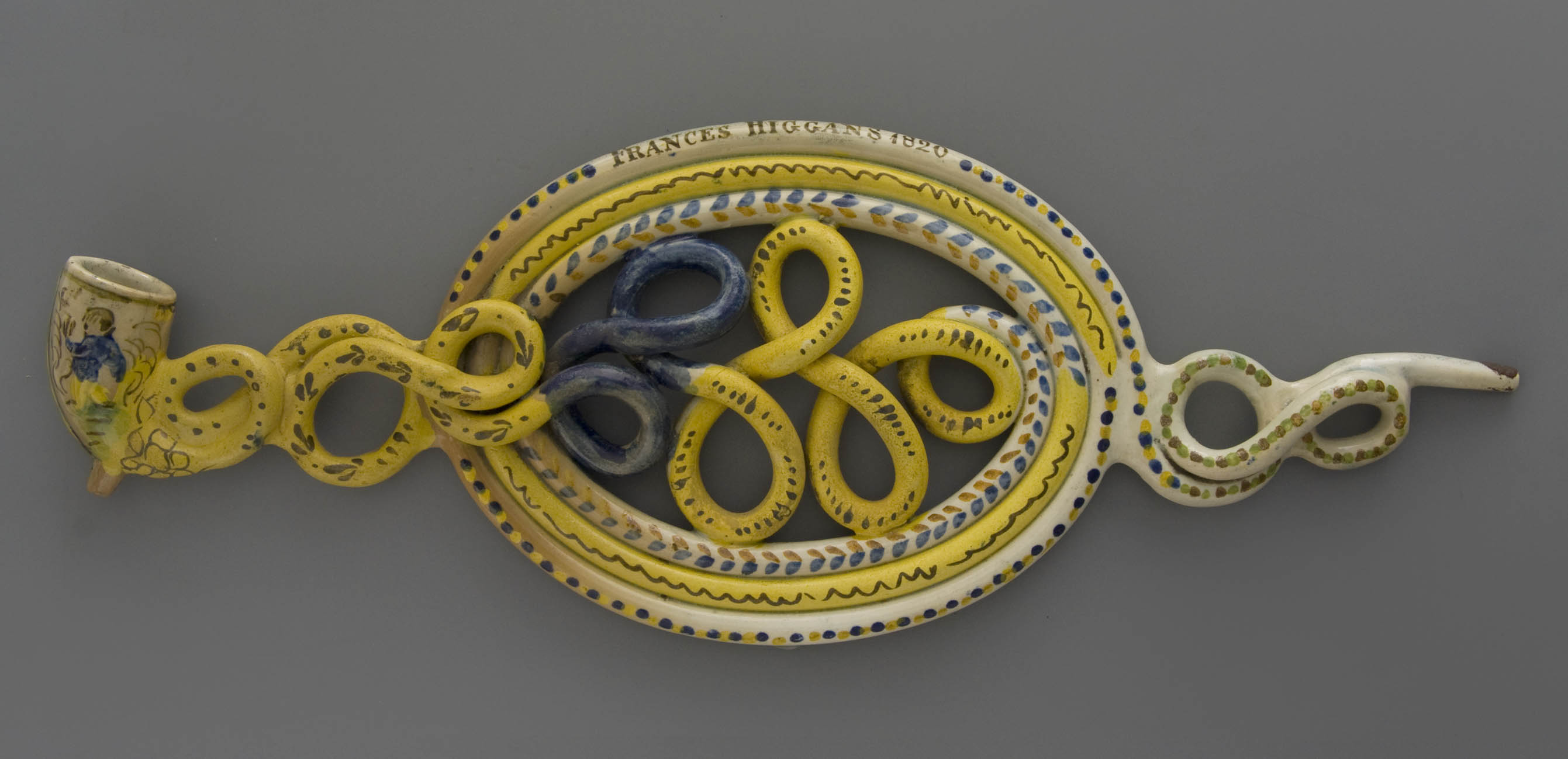

The best known are the pipes in the shape of a curled snake, the pipe bowl appears from the mouth of the animal, the tail is the mouthpiece. They were dotted in under glaze colours with a preference for ochre and blue, the colours green and brown are less common. Many of these snake pipes were made into two halves in a printing mould and then joined together. They are serial items that were in high demand, especially among the rural people, as an entertaining decorative item.

More surprising are the so-called puzzle pipes, whose stems are curled and woven into imaginative motifs. That puzzle ware is not made by hand as one would expect, but with the aid of an ingenious device with which endlessly long stems can be produced. The art was in coiling in the most intricate forms. Such a coiled pipe is depicted here and when you follow with your eye the path from mouthpiece to the pipe bowl, you automatically become dizzy. Besides numerous ellipses your eyes will make all kinds of hairpin bends and zigzag movements.

The object has a clear view side which emphasize the show function of this pipe. Yet it is a fully functioning tobacco pipe and they were also normally smoked. This specimen clearly shows the deposit of countless times of cautious smoking. The stem end is smoothed for the smoker with some red sealing wax. The pipe bowl itself has a so-called curved shape that is characteristic of the English pipes from the first half of the nineteenth century. On the bowl we see embossed a standing man with three leaves in hand on both sides.

The most remarkable is the stem. The main shape is a lying oval of three turns with pieces turned on both sides, the oval is filled with braid even on the inside. The stem is painted with dots, stripes and zigzag lines. On the upper winding the inscription "FRANCES HIGGANS 1820" is placed on demand. It indicates that this item was commissioned and provided with the name of the donor. It must be a special gift for her father, husband or otherwise for a staff member who received the pipe after years of loyal service. As a showpiece, these kind of pipes often have a long life. They were only smoked on special occasions and were given a safe place behind a glass door of the display case. So they survived over time.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 4.560

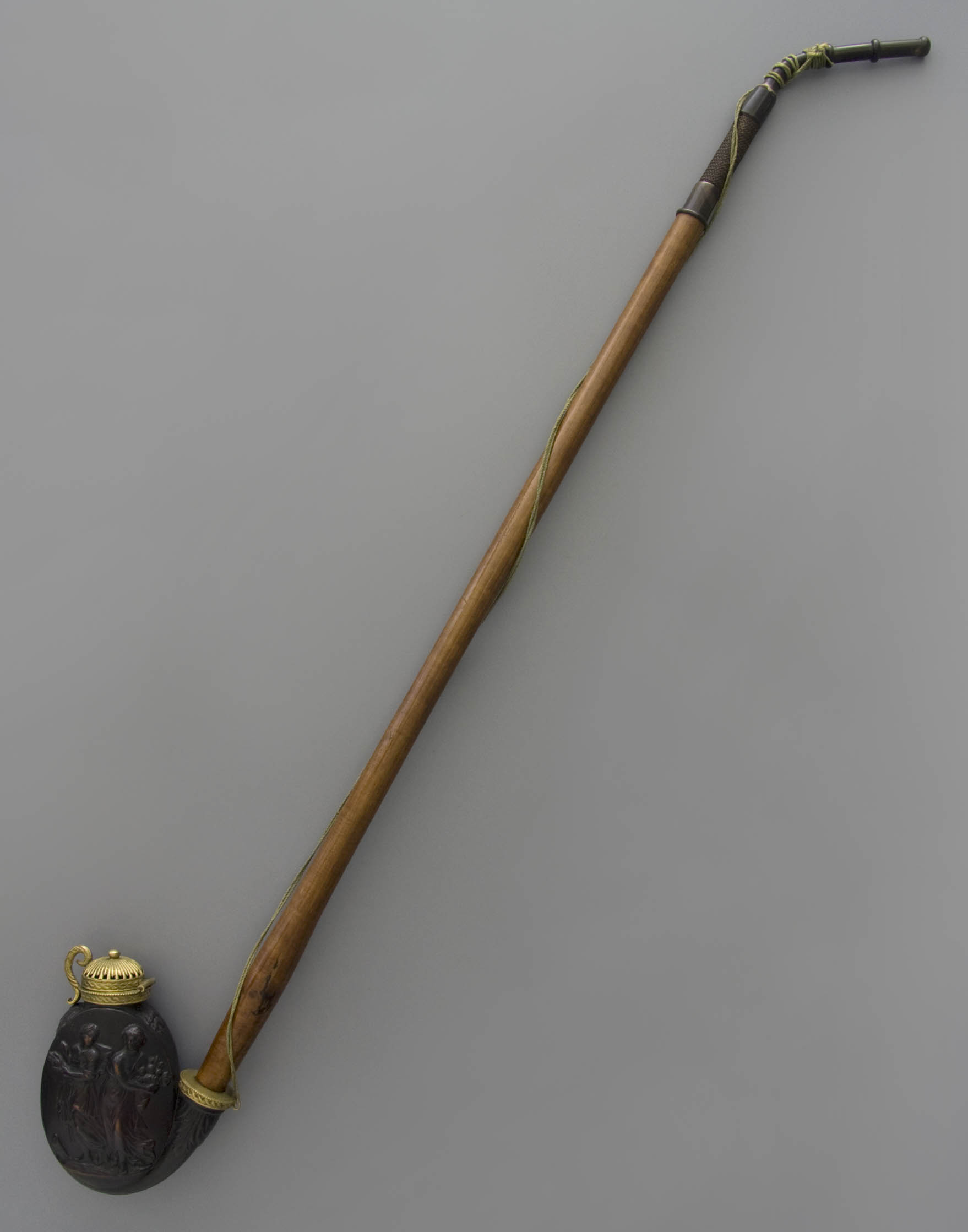

High quality from Ruhla

The shape of this tobacco pipe is special and very time-bound. It has a two-sided flattened bowl with a nice oval shape that refers to the Empire period. On both sides an extraordinarily artistic relief has been applied. On the left we see two standing women in pleated dress, the left woman with a cornucopia with fruits, the right holding a bowl with flame. The ground on which they stand shows a tree stump on the left. The right side of the bowl is similarly decorated, again with two standing women, the left with a flower basket, the right one holds three leaves.

Special about the pipe is the perfection of the oval shape in combination with the extraordinarily artistically modelled figures. It is clear that a professional has made the mould for this pipe and that, in doing so, he took classic examples as a starting point, reshaping them into the fashion of the day. The urge to perfection can also be seen in the details. For example, the bowl shows a mask head with grapes in the hair at the front. A leaf motif is arranged on the stem side. The upright stem is decorated on both sides with a palmette, a motif characteristic of the empire style.

The mounting of this pipe completes the whole. Characteristic for the time is the fine bronze casting that is fire-gilded. This work is beautiful in detail as well: watch the fluted motif on the lid with the subtle air inlet along the edge. Around the frame you can see a subtle edge of wavy lines that contrast nicely against the shaded surface. The clamping spring which holds the lid on the pipe bowl has a question mark shape that is also worked. The original stem, still preserved, is of a light wood, assembled with buffalo horn and a safety cord with tassel.

It is nice to philosophize about what the maker meant with this pipe. Did he suggest a wooden pipe with the brown colour? The material, the so-called siderolith, a fine cast clay, however, was more often used to imitate meerschaum. In that case it would be a deep-dark-brown smoked meerschaum pipe. Both options do not seem probable. More likely the mat black appearance would suggest a pipe of the coveted basalt ware: the black stoneware pipes made by Wedgwood in England that the Germans were unable to copy. By giving the surface a deep black colour, a similar result was achieved. Unfortunately, because the paint was insufficiently durable, it disappeared partly over the years and the somewhat disconcerting red shard appeared. That wear now underlines the age of almost two centuries but does not detract from the really successful time-bound design.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 18.475

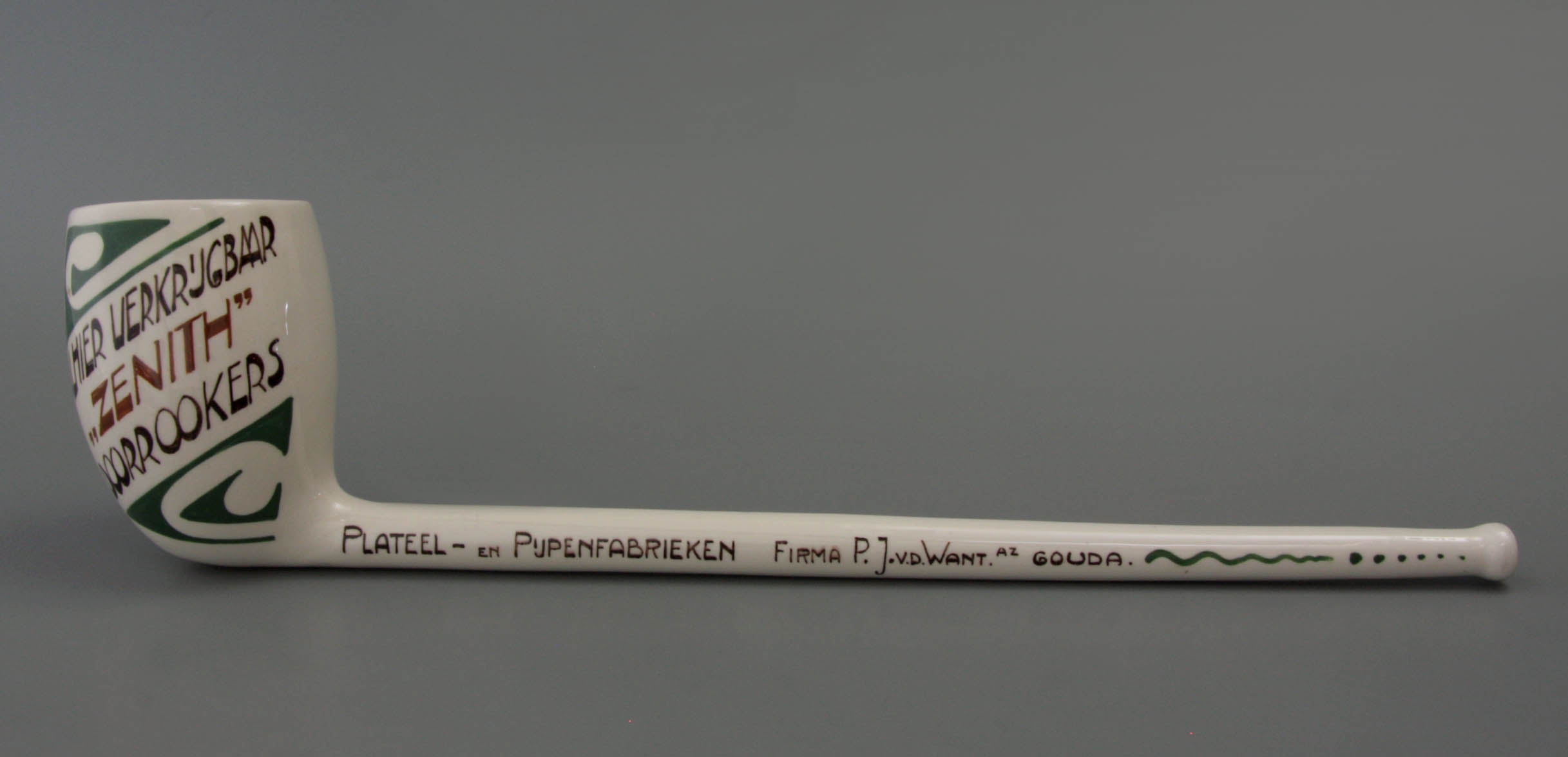

A presentation pipe from Zenith

Shortly after 1900, the Gouda pipe industry experienced major changes. Until the last turn of the century, production was done exclusively with pipe clay, around 1900 a new ceramic method was introduced. Instead of pressing rigid clay into metal moulds, liquid clay was poured into plaster moulds. The porosity appeared to be significantly larger, resulting in a pipe that smoked drier and cooler. Provided with a tight transparent glaze, a pipe with a much more luxurious appearance was created. This is how the Gouda pottery pipe was born, the pipe on which often a picture appeared during smoking, the so-called mystery-pipe. In addition, various alternatives were created, all of which were mounted in a modern way with a metal ferrule and hard rubber mouthpiece.

This newly created product led to great flourish in the four companies in Gouda who enlarged their business with this new production line. Their profit margins increased enormously and logically they advertised as often as possible to bring the new product to the attention of the smokers. When the First World War erupts in 1914, the supply of foreign pipes is impeded and these Gouda manufacturers experience good times with their new, modern slip cast ceramic pipes. With the profits they can start a production line in other ceramic objects, the birth of the Gouda pottery.

In addition to their regular products, two pipe manufacturers put a shop-window pipe on the market, intended for the tobacco retailer to advertise their normal tobacco pipes. Both pipes are a greatly enlarged version of the standard so-called doetel, the clay pipe made in a metal mould that was the most common at that time. At the Goedewaagen company, this shop window pipe is an exact enlargement of the usual doetel and shows the factory name on the stem to make the company better known. Because this shop window pipe referred to a press moulded pipe, the pipe was not glazed. With this, the factory saved the tour de force to provide such a large object with a nice even glaze. At the same time, this meant a missed opportunity to advertise the lucrative mystery pipes.

At P.J. van der Want Azn., better known from 1917 under the name Zenith, significantly more care was taken in the execution of the display window pipe. With this cast product it is decided to not only advertise their clay pipes, but also seizes the opportunity to bring the innovative mystery pipe to the attention. The manufacturer does this by placing a striking advertising inscription on the pipe bowl. For a clear message, the pipe must be glazed, increasing the reference to the luxury ceramic pipe.

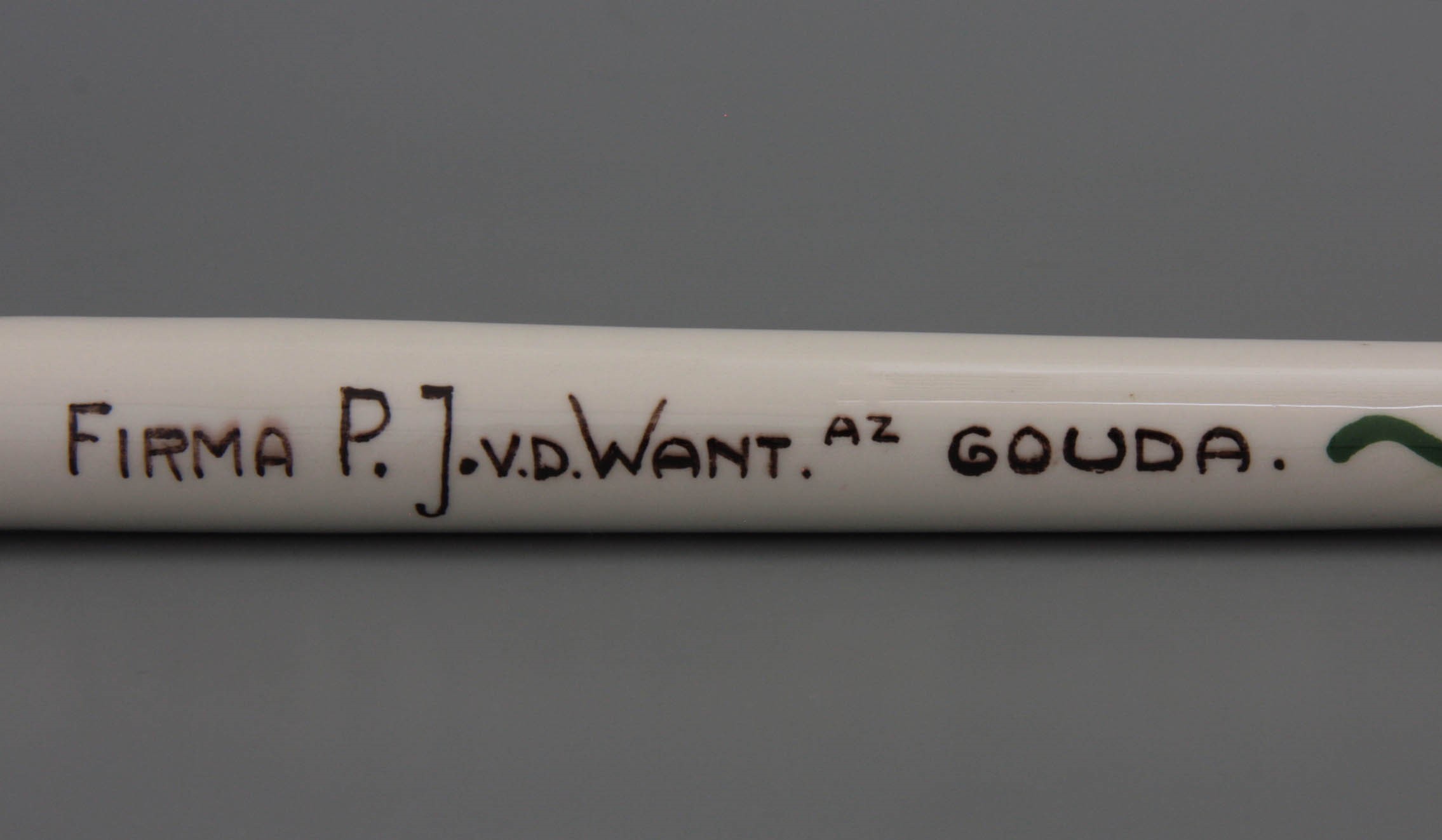

The left side of the display window pipe is chosen as a visible side, so this got a lettering on it. Across the bowl we read "ALHIER VERKRIJGBAAR "ZENITH" DOORROOKERS" (available here "ZENITH" mystery pipes) in beautiful hand-painted letters in two shades of brown. The open space at the top left and bottom right show a green curl, around 1920 a fashionable ornament that fits well with the Art Deco letters. The factory name is painted on the stem "PLATEEL- EN PIJPENFABRIEKEN FIRMA P.J. V.D. WANT AZ. GOUDA" ending with a green line and some dots. With its smoothly glazed finish, the Zenith pipe had become a precious object. The risk that the application of enamel on the long stem would fail, was great and the dropout in production would have been considerable.

Evidently such shop-window pipes were made in small quantities. They were only provided to the more important tobacco retailers who could actually advertise them. A small shop in a backstreet was not worthwhile. Nevertheless, the circulation must have been of a certain size. The manufacturer had to made a special mould and that was only profitable with a reasonable production. Numerous examples of the Goedewaagen pipe have been known, but from the glazed Zenith version this is the only known one so far. The dating of this giant pipe is around 1920.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 18.953

Porcelain as a material

Pipe bowl with three male heads and a monster

A unique design with an unexpected detail, you could call this tobacco pipe. Around the pipe bowl the designer very cleverly modelled three human faces that each share an eye with their neighbour. The three male portraits obtained their own facial expression with a smiling mouth or bared teeth. But those who look better also notice a fourth head, namely that of a monster and ironically the smoker himself has a view on that. With an opened mouth with sharp teeth, it bites into the stem set and its muzzle is hidden in the stem angle. Here, too, the animal lends its eyes to his neighbours, which makes them lie quite far apart, which is very appropriate for a monster head. All in all it is a special pipe bowl with a beautiful, yet rather creepy ornament all around.

This unexpected design was made by Johann Gottlieb Ehder, modeller at the famous Königlichen Sächsischen Porzellan Manufaktur in the city of Meissen. Thanks to the extensive factory archives we know that this pipe bowl was created in June 1743. The famous master-modeller Johann Joachim Kändler, master of Ehder, registered the design in the shape book. Incidentally, that happened only after he had made some refinements, although we do not know which one. A plaster mould was made from the design and then the pipe was taken into production. After the modelling and finishing of the porcelain paste, the first baking process followed. Then the object is glazed. In the painting department, the porcelain object was carefully polychromed and the three faces each received their own identity. To achieve a good distinction, the painter added a moustache or a goatee. The circulation of this article is not known but at Meissen this usually involved no more than a handful of copies because the customer base for such luxury items was extremely limited.

Everything shows that this tobacco pipe was a valuable item in his time. This is demonstrated by the beautiful porcelain, the careful painting but also the fine mounting. The porcelain pipe bowl is in fact provided with a silver framing consisting of an open sawn domed lid and a silver stub ring. With the aid of an equally silver retaining chain, the stem end is attached to a separate buffalo horn stem. This stem consists of two parts that screw together with a fine screw thread. The result is a usable pipe stem with a strong kink.

After more than 250 years the pipe still has its original gift box, a cassette that is a piece of art in itself. It is a rectangular box with bevelled corners and a slightly curved lid. The outside is covered with green shagreen, the inside is lined with red velvet and pink silk. The parts fit in three compartments: the pipe bowl and stem in two parts. It should be clear that such a luxury box with precious content was at the time almost counted to the category of jewellery.

In the 1740s the figural tobacco pipe was on the rise, not only in Meissen, but also at other porcelain factories. Despite the large variety of shapes, it always remained precious objects, as a gift for princes and the high nobility and certainly not for the ordinary smoker. Such luxury objects were usually handled carefully, initially by the smoker who used the pipe for a year or so. Most copies, however, were quickly promoted to a showcase because of the art value. That also happened with this pipe. Of the limited number of pipes produced, only a few have been preserved. Of this design a second is known, which is located in the museum of the city of Regensburg. That copy is made in the same print mould but has a different paint scheme.

Thanks to the powerful modelling, the detailed painting and the luxurious way of assembling and packing, this tobacco pipe is far above the contemporary smoking pipe. The art and rarity value makes this article a desirable object. That is why it nowadays only happens sporadically that such an item appears on the market. As far as this model is concerned, no third copy has yet been found, but perhaps this web page is the incentive!

Literature: Don Duco, Pijpenkop met drie mannenhoofen en een monsterkop, Amsterdam, 2005

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 15.078

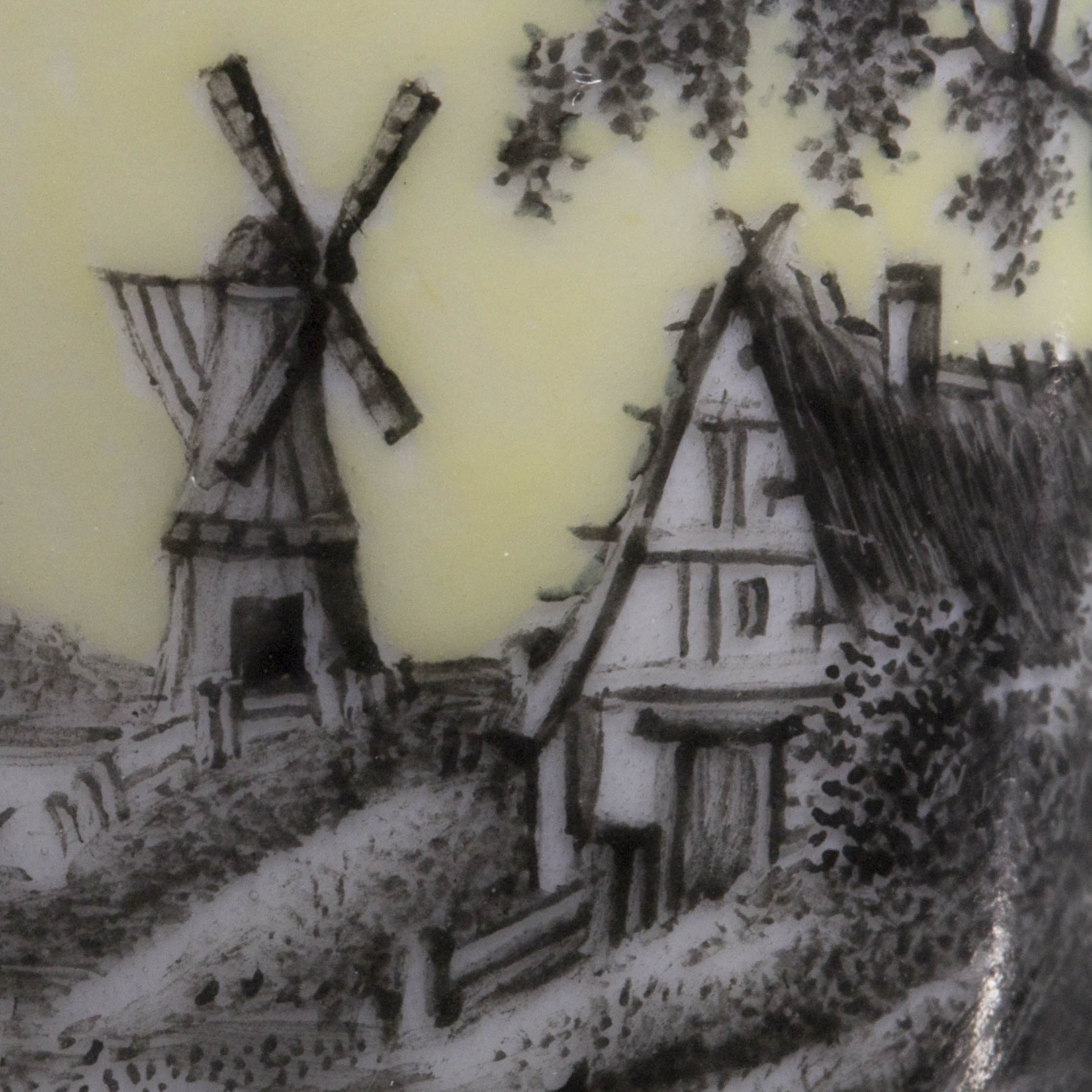

Berlin stummel with Dutch landscape

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a new pipe shape was born in German porcelain factories. It is the Stummel, the shape based on the Gouda clay tobacco pipe. The pipe bowl is oval in shape and equally well balanced as the Gouda example. To get a distinguished appearance, this pipe bowl is even slightly extended in height. At the transition from the bowl to the stem a heel is applied, while the stem is in the same angle as with the clay pipe, at least 120°. What makes the stummel so collectible is the meritorious painting. We see these qualities especially in the first period, after the Biedermeier time the product becomes a mass article in ever diminishing quality.

One of the highlights of porcelain painting shows this stummel from the Königliche Porzellan Manufaktur in Berlin. In addition to Meissen, the Berlin manufacturer enjoyed great prestige as well, being one of the leading porcelain factories in the world. Their great quality of the painting is clearly reflected in this pipe. The image on the front of the bowl falls within a standing oval framed by a double wide band of gold leaf that is artfully pierced and resembles an open-cut band. In this oval an extremely finely painted representation has been applied. This painting is not done in natural colours but in monochrome black, the so-called encre de chine, which testifies to a chic austerity. Pictured is a sloping landscape where a river flows through, right under a tree is a farm, in the back we see a high windmill. In the foreground are a few people at a boat. Despite the small size, the painting was done with the utmost care, it seems that the painter used a brush with only one hair. Quite unexpectedly, the clouds have been coloured with a plain, bright yellow background, a fashion colour for those days that is a bit unexpected for us now.

The date of this pipe is between 1810 and 1820. Production at the German porcelain factories was already highly standardized at that time. For example, one used a format number for the different sizes of stummels. This format number was often printed on the heel, in other cases on the stem. The figure "8" was the most common size, which we see very inconspicuously on the heel of this pipe bowl.

The luxurious painted pipe bowls were mounted with a silver lid edge on which a hinged cover is mounted. With this pipe, the lid is more luxurious than average. Around the bowl a silver pearl fillet is applied just under the air inlet consisting of a sawn edge with upright ovals, as it were, following to the oval picture frame. A so-called clamping spring serves as closure. The pipe bowl is complete with its original silver spherical moist bag with a safety chain to the bowl. This bullet-shaped bag also indicates an early date. All in all, this pipe is a luxury example of a pipe bowl from a highly developed porcelain factory. The careful mounting underlines the special quality.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 4.562

A regiment of Napoleonic soldiers

In the porcelain industry, there has always been great interest in figuration of the pipe. It was the authoritative German factories that had come up with unexpected porcelain designs in the eighteenth century, such as endearing pug-dogs turned into pipes. In the nineteenth century that fashion was partly taken over by the French. The porcelaine de Paris and the work of Jacob Petit might have made a special contribution to the figural pipe, although we do not know the full details of it yet. In addition, some series of figural pipes have been created, which also amaze us. An exclusive set of Napoleonic soldiers, for example, was produced by an unknown factory.

From this series, of which the Pijpenkabinet holds 22 specimen, one copy has been chosen for discussion because it is a really exceptional example. It shows a general with a two-sided stitch on the head with a high feather plume in the colours white, red and blue. Everything about this pipe is over the top, that goes for the flamboyant modelling, the fine finish and the painting in bright colours. Finally, accents were still heightened with dust gold.

We can be certain that these pipes are modelled on existing costume prints depicting the different regiments of soldiers. The modeller studied meticulously the endless series of costumes and he completely faithfully reworked them, an assignment he took very seriously. This went so far as to include the portraits of the depicted men in harmony with their military status. We see faces ranging from iron-eaters and worn-out elderly fighters to immature persons under twenty years of age. The disadvantage of these portraits is that the lips are sometimes too feminine: a plum mouth together with the blushing is not really appropriate for a soldier.

Except that the pipe bowls can be admired aesthetically, we can also appreciate their technical details. In that case, not the artistic merit comes first, but rather the functionality. Well, in terms of usability as pipe, the pipe bowls do not work perfectly. In the case of the general discussed here, for example, the feather plume far above the bowl opening is clearly inconvenient. During smoking, thumb or finger easily hang behind, while emptying the pipe is almost impossible. Because the interior of the bowl is strongly shaped to the outer design of the pipe, it resulted in a rather irregular shape. This is not really convenient for the smoker because inevitably tobacco remains behind in different places. Also the stub of some pipe bowls is not very pronounced, so that it has a risk of breaking when the stem is inserted.

On the inside of the stub, these pipes show an incised shape number in Roman numerals. Those figures increase to far in the forty, so assumedly the complete series has consisted of dozens of different soldiers. This is more an early example of a collecting item than the need for the market to have new models available. Did the manufacturer follow his hobby here? In any case, he ensured that his customers who could afford it would receive a special collectable that could be supplemented almost infinitely. We can assume that the series did not come about in one go, a new copy will be designed at regular intervals. Examination of the different specimens and especially the use of the gold also shows a certain periodization. For example, the gold leaf ornament on the underside of the bust is slightly more extensive at first, while the motif is sometimes even almost gone with later pipe bowls. As a matter of fact, this gold leaf was applied to obscure the prints of the baking support.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 19.501

The magical meerschaum

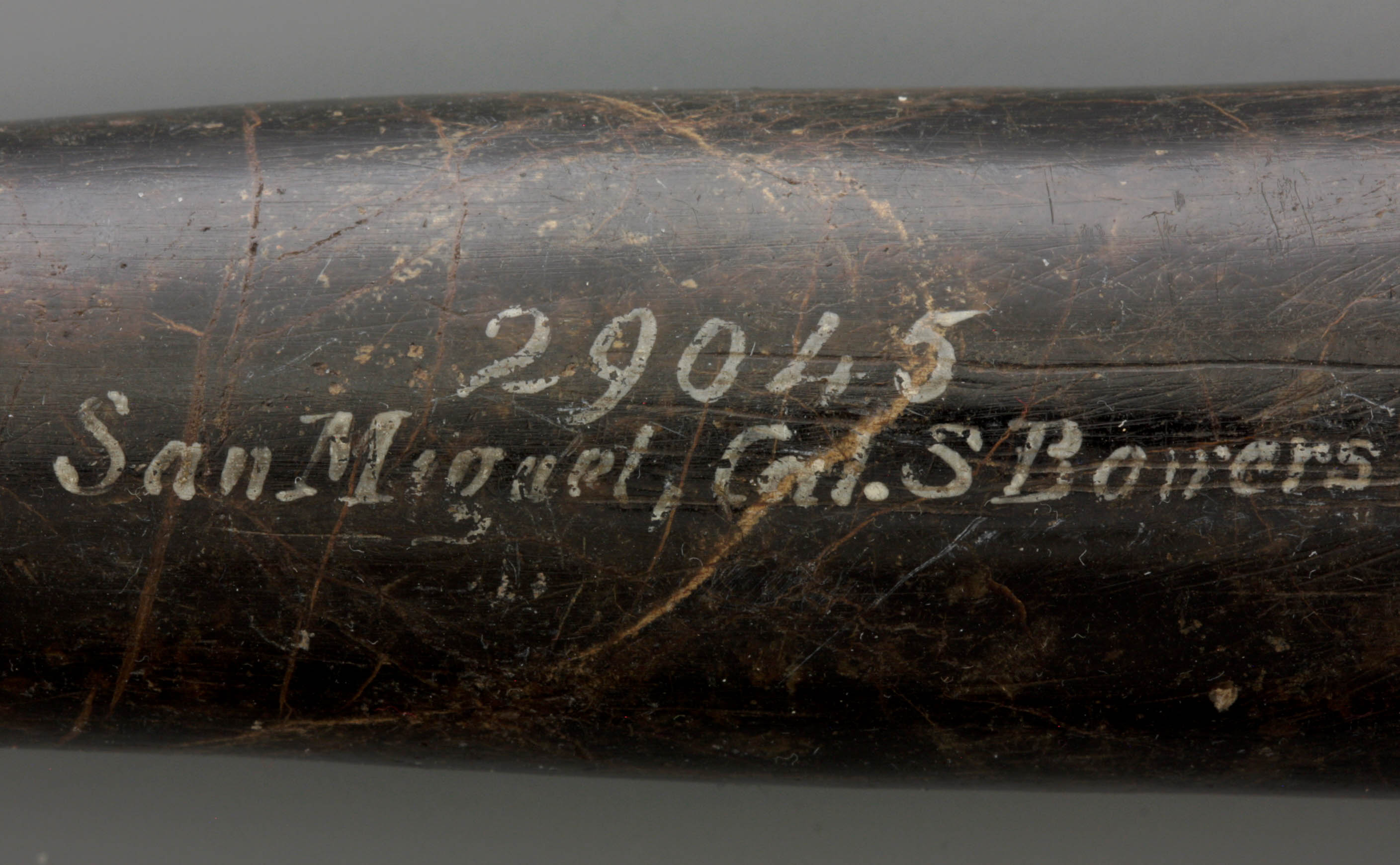

The horses of the San Marco

This seemingly ordinary undecorated pipe bowl in case has a special history. In terms of shape, this pipe with its reinforced bowl base and round bottom is not special. This so-called bag shape is already in vogue in the eighteenth century and this specimen is a very pure example. In the nineteenth century, tens of thousands of pipes will be made in this bag shape. In addition, the quality of the meerschaum can differ, from the most finest first-rate pieces that are maximally light weight to the less popular heavier blocks. For this pipe the best raw material is used which is not surprising. The pipe bowl was intended to be provided with a really special mounting.

At special request of no one less than Emperor Napoleon himself a luxuriously mounted pipe was ordered in 1807 at the skilled goldsmith D. L'Honorey, working at the Quai des Orfèvres in Paris. It was to be a gift from the emperor to his marshal who had made a special act of war shortly before. He conquered the city state of Venice and presented to his emperor as a trophy the famous horses of the San Marco. The four more than life-sized bronze horses had decorated the most important church of Venice since time immemorial and now arrived in Paris.

Very appropriately, the appearance of the imperial gift had to refer to the martial act. L'Honorey did this by designing a lid in the form of a military helmet with visor and placing the four horses of the San Marco as the crest on top of this helmet. The silversmith was not only exceptionally inventive in the artistic part of the design, but also in the technical execution. The lid was high and heavy and should easily be opened to give access to the pipe bowl. At the same time, it had to stay steady while smoking. To achieve this, L'Honorey used a double hinge with an ingenious closing mechanism. By pressing the visor, it slides up and unlocks the lid, which then opens completely with three clicks. The helmet folds back further each step until the pipe bowl is completely free. To make the appearance even more luxurious, parts of the silverware were gilded. Finally, a case maker made a beautiful, fitting casing, internally lined with satin and velvet, on the outside with red leather. The edges were neatly trimmed using stamps with gold leaf and three hooks made sure that the case was properly lockable.

Given the traces of use on the inside of the pipe bowl, the Marshal has not been an avid smoker. The pipe has only been used a few times and was then carefully stored for generations in the casing. Who afterwards have been the owners of this imperial gift remains unclear. The object surfaced in the Parisian antique trade in 1982 and was bought by one of the most renowned Jewish antique dealers in Amsterdam. Twenty years later this special object was handed over to the Pijpenkabinet.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 16.425

Pipe with two river gods

In artistic terms this is the most beautiful pipe from the Pijpenkabinet collection in Amsterdam. It is commonly referred to as the Tweestromenpijp (two rivers pipe). According to tradition, father Rijn and Lorelei were depicted with the arms of a double-headed eagle. The pipe would be a gift from the Habsburg House to a member of the Russian family of czars, although for the rest details remain vague.

Both sculpted persons are shown as stream gods. The Neptune figure fully meets the iconographic pattern. He is depicted as an old man with moustache and long beard, with a wreath of pointed reed leaves around his head. As usual, Neptune is naked with a rag over his loins, as an attribute he holds an oar that brings a vertical accent into the image. His right arm leans on a wide urn from which a river arises. The woman on the right carries vine-like leaves around her head, with the left hand she leans on a watering pitcher, which gives her the title of goddess of the river. At the base is a standing coat of arms with double headed eagle above which the famous Hungarian imperial crown. Around the pipe bowl the scene continues with reeds in which reed plumes on the right and shrubbery left. The sketch has been worked out completely which makes you almost forget that a pipe bowl is hidden in the centre.

At the rear, the pipe stem emerges from the scene, which is smooth and thickens to a cuff towards the end. This cuff is decorated with a wide band with stylized leaf motifs and c-volutes. The cuff is mounted with a silver plate with punched motifs soldered along the folded edge. A conical stem holder is placed centrally on this plate. The silver shows traces of gilding.

When we consider that the basic shape of the pipe bowl is an Hungarian, a high cylindrical shape with a round bottom and an ascending stem, we see that the decoration on the different sides is unevenly expanding. That unexpected asymmetrical shape of the pipe bowl may be related to the method of the carver. His artistic ability enabled him to adjust the figuration to the block of meerschaum available to him so that he could use the raw material to the maximum. He was therefore not rigid and cut away what was undesirable in the decoration but made optimal use of the material and thus came to an unexpected composition. If one looks through the eyelashes, one can still see the original shape of the meerschaum lump.

There is something strange about the handed-down attribution of the pipe to Rhine and Lorelei. The old river god can very well represent the Rhine, one of the longest and most famous rivers in Europe. The Lorelei is not a river but a dangerous rocky point in the German Rhine valley, personified by a woman who watches over the passage. Therefore the name does not match the representation. Based on the fact that the pipe is an Austrian gift, we should perhaps look for the real meaning more eastward. If we identify the ancient river god as the Danube, the second largest European river, the younger and smaller river goddess can represent the Moldau. The Austrian imperial coat of arms then gets a logical meaning because both rivers lie within the Habsburg Empire.

Because of the high artistic content we tend to attribute this pipe to a Viennese workshop. Determining meerschaum pipes to production site is not easy due to lack of knowledge. Vienna is always seen as the main city for artful meerschaum carving, the role of Budapest is always underexposed. But other meerschaum workers were active in other cities as well. Yet that Viennese attribution for this pipe is justified. The exceptional composition and the beautiful effect elevate this object above all common pipes of that moment. That is why this piece deserves to have served as a royal gift. Seen from the Vienna court, this pipe bowl should certainly be made there. Given the decoration, it must have been between 1835 and 1850.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 1.485

Pipe in a rosewood box

A valuable pipe deserves to be stored safely. This usually happens in a pipe box or pipe rack, which used to be found in almost every household. Some pipes, however, are stored individually, in a box or close-fitting casing. A nice example of this is the rosewood box with rectangular shape that can accommodate a single meerschaum tobacco pipe. Below the flat lid we see five compartments. Left is a spacious and deep compartment for the meerschaum pipe bowl, next to it and behind there are shallow pockets for the three parts of the ivory stem. At the far right at the front is again a deeper compartment that serves the three-tassel safety cord. The front of the box is provided with a lock with heart-shaped lock plate of mother-of-pearl. As usual, the box is internally lined with red-brown velvet-like fabric so that the parts will not be damaged.

The tobacco pipe that is stored in this box is not of a great peculiarity, but apparently the smoker's favourite. It is a relatively common meerschaum pipe bowl of the so-called Hungarian shape. The base of the pipe bowl is round and merges into a rising stem with a cuff. At the base, the pipe bowl is provided with a popular motif: a shell shape in relief. That motif consists of six outlined lobes and that is remarkable in itself. It is common that this motif consists of an odd number of lobes so that the middle one runs over the centre of the pipe bowl. This is an unusual deviation from that habit.

The pipe-bowl is according to general use in the nineteenth century equipped with a silver hinged cover. That lid has a lens-shaped top and rests on ten balls that provide an equal air inlet around the bowl. The lid clamps down thanks to a spring in which three tobacco leaves can be seen on a ball. In the bowl ring of the lid we usually find the silver marks, in this case a "13" mark and the makers stamp or year letter "R". The cuff is also reinforced and finished with a ring in silver with a smooth stem holder and locking eye.

Based on the silver marks, it must be a German product. However, what often happened is that parts from different production centres elsewhere were assembled into a complete pipe. The roughly turned pipe bowl for example could have been supplied from Austria or even from Turkey. The accompanying stem can also be made in a different location, because turning ivory is a separate discipline. The same applies to the box, which does look more English than German. The date of this object must lie somewhere between 1840 and 1870. Most certainly, the pipe is cherished in the box because even after a century and a half the tobacco pipe still is in perfect condition.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 19.514

A presentation piece with bloody battle

Because of its large size this meerschaum pipe fits into the category of extraordinary tobacco pipes. The bowl of this showpiece has a height of no less than 23 centimetres and shows around a carved scene of a bloody battle in which sixteen fighters attack each other with axes, knives, swords and bows. In the centre of the scene we see an Arab on a rearing horse who is attacked by a soldier who pierces his chest with a dagger. It is a beautiful depiction that undoubtedly reflects on an existing print of high quality.

In addition to the swirling decoration that has been skilfully worked out with all sorts of interesting details, there is the shape of the pipe bowl itself. With its high cylindrical bowl and heavy stem that flows smoothly from the bowl and ends in a cuff, the shape of the pipe is very characteristic of the 1860s and later. Around the pipe bowl the battle scene decoration follows the shape of the pipe in an attractive bas-relief that is sufficiently picturesque to radiate a great naturalism. The base of the bowl is overgrown with a carved winding foliage, continuing on the stem, alternated with small rocaille-like ornaments. Those motives form a welcome ornament to the long, rather boring shape of the bowl base and stem.

Special is the mounting with a beautifully openwork silver hinged cover with facetted edge, beautifully engraved. The lid itself has the shape of a ten-sided crown consisting of panels with an embossed standing knight. The inside of the crown is cut open and ends in a point shape. The clip spring has an elegant curl. Despite the white colour, the crown is not cast in sterling silver but made of a lower alloy silver. Because most parts of the mounting are gilded, the gold colour obscures the somewhat grey colour of the silver. Two rectangular hall marks are stamped on the edge of the cover with the letters "JK", a mark that appears more often on pipe fittings. The cuff mounting is made of the same material and also features facets and engraving.

All characteristics of this pipe indicate German origin. This applies in the first place to the meerschaum, which we count to the category of mass meerschaum or pseudo-meerschaum. The pipe is not cut from a large stone, but is pressed from a composite of which meerschaum grit is the main raw material. In the period of origin, between 1870 and 1885, large pieces of meerschaum were extremely rare. German factories had long experimented with imitation meerschaum with particularly favourable results. The meerschaum powder was mixed with an adhesive and then moulded. Then it could be cut just like real meerschaum. It even had an advantage for the cutter: the stone was completely homogeneous which made work a lot easier. Finally, the Germans were also masters in creating the patina of the pipe so, even unused it could get the appearance of a long-smoked pipe.

With its solid shape and transparent lid, this showpiece has been a masterpiece among the smoking equipment of a German nobleman. For us in the 21st century, however, the question remains unanswered as to how this pipe was valued at the time. Was the owner aware that he did not have a real meerschaum? Certainly he would have known that the desirable patina was not obtained by smoking but was artificially applied. Apparently, it did not bother him in his pomp and pageantry. Whether the pipe really impressed contemporary connoisseurs remains the question. Anyway, with its somewhat pompous appearance, this product fits perfectly into German culture as we know it from the various country houses. Refinement of material and technology is more an Austrian affair than a German custom. We can see that even in the tobacco pipe.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 17.550

European wooden pipes

Wooden pipe bowl with mirror monogram

The bowl shape of this early wooden pipe is called kalmas, a shape that originated in Turkey. Already in the seventeenth century it became known about Central Europe and is generally followed. The kalmas is characterized by a bulging round lower part of the pipe bowl, a top part that narrows, while the opening widens slightly outwards. The short truncated stem smoothly emerges from the bowl and ends in a slight widening mounted with a silver stem holder.

All around the bowl this wooden pipe bowl is embellished with carving. The main motif is located on the front, placed inside a crowned circle. It shows a mirror monogram consisting of the letters J and A artfully intertwined, both plain and mirrored. This created a beautiful balanced contour that was loved in the period of Louis XIV. The medallion itself is again framed by two palm branches, the symbol of honour. The rest of the pipe bowl is decorated with curled foliage that looks most like acanthus. These leaves are evenly spread over the surface, continuing to the stem.

Such a beautifully carved wooden pipe was regarded as luxury smoking equipment at the time. Completely in style they were provided with a silver mounting. The hinged cover on the bowl was more or less standard for central European pipes. It’s dome-shaped cap with button on top of a circle of flowerlike lobes, shows asymmetrical openwork sawing. The stem end has the same silver fitting, which gives greater strength when mounted on a separate stem. A locking eye serves for secure attachment to this detachable stem. Both mountings are fixed with a sawn edge of leaf motifs that fold over the wooden bowl. In order to appear true to nature, these leaves are engraved with a few engraving stitches.

Given the skill of the carving, this is a regular product, made in series by a pipe maker who understood his métier. Because of the mirror monogram, however, it appears to be an object with a personal accent, made on special order. This monogram does not have to be from the smoker himself, who ordered the pipe. It also happened that a pipe was donated as a gift and that the initials of the donor were cut out. In both cases, however, it is the monogram of the client. The person behind the initials will never be traced.

It is difficult to assign a date to this pipe. The shape was already developed at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the fitting seems to be of a somewhat later date. That could argue for a date between 1730 and 1750. Based on the fact that the pipe industry was often very traditional, such a pipe bowl could even have been made up to fifty years later. Yet it does not seem that way, because, inevitably, in that case a few later style features would have crept into the decoration. We assume that the place of production must have been Germany, although it is not possible to specify where.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 16.716

As curious as meritorious

With some pipes, the maker loses sight of the purpose of use and is focussing exclusively on the design. That seems to be the case with this wooden tobacco pipe whose bowl is shaped as a sitting owl and the moisture reservoir represents another bird. If one is not very keen on decorating and figuration, this is an abomination. On the other hand, anyone who has carved a figure out of wood himself shall realize how much craftsmanship is in this pipe and how original the design is.

Let’s look at the pipe bowl: it follows the usual oval bowl shape, customary for that period and is equipped with a lid as is common in most German pipes. However, the design of a sitting owl is very convincing because the animal exudes the patience and dignity typical for an owl. The pattern of the feathers has been cut out in detail with the utmost care. Very appropriately, the air holes for the lid are quite inconspicuously hidden in the nostrils in the beak of the animal. By adding glass eyes, he gets the sympathetic look of a toy animal.

In the end, this pipe is completely functional. The beautiful fine wood has been doubled on the inside with a sheet-metal mantel to protect it from burning-in. The German pipe makers have been doing that since the seventeenth century. In addition, the drilling to the stem and the moisture reservoir are optimal so that the pipe guarantees a good draft.

The moisture reservoir itself, also a standard part of the German Gesteckpfeife, is designed in a less natural way. The decoration follows the usual bag shape so that the swan with its long neck gets a quite artificial posture. Did the creator attempt to express that the swan had fallen into the claws of the owl or did he not see a better solution for the design? Again, comparable glass eyes were added, which were considered to be more pronounced than to drill pupils into the wood.

Fortunately, the pipe was preserved as a whole with its original mounting of stem and mouthpiece. Here we see how strong the Gesamtkunstwerk (overall work of art) is. The materials including the carving of the stem fit in seamlessly with the pipe bowl. Moreover, the alternation of the brown wood and greenish-black buffalo horn is very attractive. The stem shows a rhythmic pattern of diamond shapes. The horn work, possibly made by a friendly horn turner, has the same rhythm of more sharp points. Colour and material texture provide both strong unity and an attractive contrast.

Those familiar with the design of the German pipe will see that the maker has created a beautifully balanced pipe. It has become a recognizable German Gesteckpfeife, but with an entertaining image of high artistic level. What is unfortunately missing when discussing this pipe is the exact origin. No matter how German of origin it looks, there is no clarity about the exact region of origin nor about the dating. The pipe probably looks more recent than it is. We estimate the date of creation between 1860 and 1890.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 19.837

Pipe of the Prince of the Netherlands

Without doubt, Prince Bernhard, consort of Queen Juliana, is the most famous Dutch pipe smoker of the twentieth century. For the Prince, smoking was not only a hobby for an optimal taste experience, but also an expression of fashion and style, a part of his image, as important as his white buttonhole carnation. For the prince, his pipe became an object to flaunt, always appropriate for the occasion.

Prince Bernhard's favourite brand was Dunhill, the brand for smokers who can distinguish and hanker for quality. On many of his portrait photographs the subtle but exclusive mark of the white dot on the mouthpiece can be discerned. But a prince with panache and charm used the pipe not simply as a status symbol, but especially as a fashion accessory. At no individual one can see so well that the choice of his pipe corresponds to the clothing as it is fitting to a specific occasion. Sporty or just dressed, modest and unobtrusive or just flamboyant and extravert, the pipe goes along with all expressions, if well chosen. Especially for that choice, the prince had the discerning eye: during painting a rusticated meerschaum with gentle bend, for a gala an implacable straight dress with a modest silver band.

But a pipe is not merely an expression of fashion. It is first and foremost a commodity item, comfortable in the hand, with a bowl size that matches the cut of the tobacco and the duration of the moment of smoking. The prince bought his pipes with these criteria: inspecting the shape personally, see if they were well handeable and fit his posture. Fitting a pipe in front of the mirror was not necessary for the prince, he knew how to make his choice. Although he listened carefully to advice, he always took the decision himself.

One pipe smokes better than the other, that secret cannot be provided at purchase but the smoker has to experience that by trial and error. One of Bernhard's favourites was the Dunhill pictured here from the year 1992. An ordinary shape but a top brand. A beloved pipe because it smoked so well, but also because the Prince received this particular pipe as a gift at a personal jubilee. For that occasion the family had engraved the coat of arms of Von Lippe-Biesterfeld in the silver band around the briar stem end. Thus this pipe became even more personal than all other Dunhill’s that the prince possessed. Since then the pipe has been smoked almost to its end, until the pipe repairer even had to put a silver band around the bowl to prevent bursting. Let's be honest, even a Dunhill wears through use.

After ten years of loyal service, it was time to give the pipe a new destination. Prince Bernhard offered it to the Pijpenkabinet, accompanied by a portrait on which he is depicted with his favourite. An ode to pipe smoking but also a token of appreciation for the piece of historical work that the museum performs in preserving the culture of pipe smoking.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collection Pk 16.874

Other European pipes

A clay pipe translated in ivory

The Gouda pipe of white pipe clay has been a source of inspiration for pipe makers for centuries. The bright white colour, the outbalanced bowl shape and the extremely slender stem were admired worldwide. Unfortunately, hardly any materials can be found that makes it possible to imitate the appearance of the clay pipe. The pipe shown here deserves a price in that respect. The pipe was made by an ivory worker from Dieppe after the example of a clay pipe.