Highlights of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Hoogtepunten uit het Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Publication Year:

2020

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Delft jar with Amsterdam weight house

There is a lot of confusion about Delft tobacco jars with a specific egg shape, blue painting and a brass lid. Contrary to popular belief nowadays, they are not jars for cut tobacco. At the time they were used to store snuff tobacco. Furthermore, the pots are exclusively intended for the tobacconist. That is why many of them are made in series. On the shelf in the store, these jars contain various types and flavors of snuff. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth century these jars could be found in every Dutch tobacco shop. Of course varying in size and painting. The shopkeeper used them daily to scoop the requested amount from the jar into a paper bag and put the jar back on the shelf. The authenticity can be seen from the worn foot by the regular sliding over the shelf. By tapping the snuff scoop and closing with the brass lid, the top edge or lip is always slightly damaged.

As usual, these Delft snuff jars have a specific egg shape with a flat bottom, the body bulging from narrow to wide to the top, perfect round schoulder and a narrow outer lip. The lid edge intended to seal fresh snuff airtight, with a piece of parchment or pig's bladder sealed with a string. The visible side of the jar is painted in Delft blue with subjects related to the content. Often these are traders with bales of tobacco, a sailing ship, sometimes accompanied by Indians, supplemented with names of tobacco varieties that are characterized by a certain smell. Regularly there is also a number series, especially when a store could offer a wide range of flavours.

With this hefty snuff jar, it is not the name or the number that dominates, but the depiction. We see a weigh house surrounded by two leafy branches. Below the image, the number "N.16" is placed in a horizontal cartouche. That relatively high number indicates the importance of this tobacco shop, where at least sixteen such pots were lined upon the shelf.

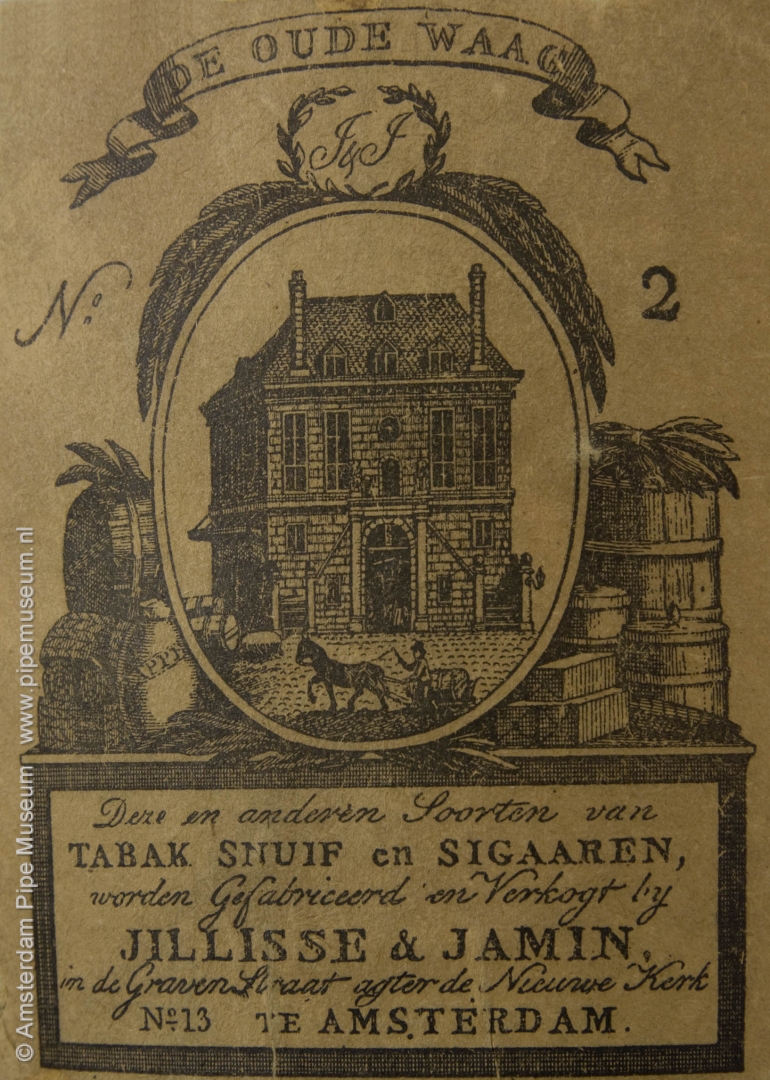

We are quite fortunate that a vignette of the tobacco merchant who carried this brand is stuck on the back of this jar. As a result, we know more about the origin. In the picture we see the same weighing house with a man in front of it on a horse-drawn carriage. It represents the so-called "Oude Waag" in Amsterdam, not the now well-known Waag on the New Market, but the old weight house on Dam square. This building was demolished in 1808 because it obstructed the view of King Louis Napoleon from the Palace. This very functional edifice had been on Dam Square for centuries. It was originally built in 1341, replaced in 1565 and rebuilt again in 1777 in a classical style. We see that last version on the print and on the front of the jar. It is a kind of Waag that we know from countless Dutch cities such as Leiden and Gouda. Most striking is the large central gate behind which we see the enormous weighing scale. But unique to this weigh house is the double staircase on either side of the entrance.

At the top of the label is a small open cartouche "J&J", above it floats a text ribbon with flapping ends reading "DE OUDE WAAG" (the old weight house), on either side "NO. 2". At the bottom we find the address of the tobacconist with the text "DEZE EN ANDEREN SOORTEN VAN TABAK SNUIF EN SIGAAREN WORDEN GEFABRICEERD EN VERKOGT BIJ JILISSE & JAMIN IN DE GRAVENSTRAAT AGTER DE NIEUWE KERK NO. 13 TE AMSTERDAM" ("these and other types of tobacco, snuff and cigars are manufactured and sold at Jilisse and Jamin in Gravenstreet behind the New Church number 13 in Amsterdam"). The Gravenstreet still exists: a narrow street that runs around the New Church. Number 13 turns out to be the corner building with the current Eggertstreet, formerly called Behind the New Church. Cigar warehouse "De Drie Kistjes" (The Three Boxes) would remain here until a little after 1900, incidentally in a new building from 1897. In the fourth quarter of the eighteenth century, the company Jillisse & Jamin apparently chose the newly renovated weigh house as its brand name, using the well-known building that was just visible from the store. That seems like clever marketing if your store is rather hidden.

The tobacco jar was made by the Delft pottery De Vergulde Blom Pot (The Gilt Flower Pot), which was owned by Paulus Verburgh. We know this thanks to the signature in blue on the bottom where "8 B: P" is written. The pot will have been made around 1780. The pottery factory, which dates back to the seventeenth century, continued to exist until 1841.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.823a

A faience vase for Gouda pipes

This beautiful urn is generally called pipe vase. A vase that is meant to exhibit the long clay pipes in a pipe or tobacco shop for selling. This custom was not or hardly known in the Netherlands. The clay pipe was too general and was sold directly from the transport basket. In many European countries, however, these products were significantly more expensive and therefore offered in a more exclusive way. The pipe vase was the most appropriate way to present the precious pipe.

A real pipe vase is not an arbitrary vase in which pipes could have stood, but is an article that is specially intended for exhibiting long Gouwenaars, Gouda pipes. This is expressed in the shape of the vase. This must be stable in order to hold the fragile goods properly. In addition, that also appears from the applied decoration should be related to the function. In the vase discussed here, the shape and decoration are perfectly united.

This beautiful vase has a special shape with a flat foot and a round body from which a long slender neck rises, ending in a thin, rounded edge. The narrow neck determines the position of the pipes, which are fairly upright, so that the vase occupies little space and one will not easily walk against the clay pipes. The limited diameter of the neck also refers to thin stemmed pipes or in other words pipes of the best quality. The sturdy foot and the relatively heavy body ensure that the vase will not easily be knocked over. The obliquity of the object that is clearly tilted is remarkable. This may indicate carelessness of the potter but rather has a practical reason. When the vase was placed on a cupboard, this gave an optically positive effect. In addition, the inclination made that the rear pipes wouldn’t hit the wall.

The painting gives the vase a clear view side. The back of the object remained unpainted, which implies that this side was facing the wall. Very appropriately the same type of vase is painted on the front, albeit that this one shows two s-shaped ornamental ears on the neck. The painting is done in two colours. Purple is used for the so-called trek or draft, the contour lines, the painting is then filled in with blue, so that the purple almost seems to disappear. What strikes is that we now see the pipe vase in use: seven long clay pipes are displayed from the neck. The image is placed in a c-volute garland, decorated with small leaves, ending in a floral top. By painting a vase on a vase, a surprising repetition has been achieved.

The idea of the pipe vase must have been copied from the apothecary jars from the old pharmacy or from the tobacco jars from the snuff store. A fresh bright blue painted vase gives standing and does well in a shop interior. That such a vase was meant for a luxury store is evident. It is a specially made item that certainly was not on the regular market. Incidentally, it was not a very practical tool for the shopkeeper. Arranging the pipes had to be done with great care to prevent fracture. This makes it a showpiece rather than a vase to serve customers.

We can speculate about the contents of the vase: were regular pipes in it, while the merchandise was traded from the pipe basket? It is also possible that the gifts of the pipe baskets, a special decorated pipe, were put in the vase until they could be sold one day at a serious price.

As far as the dating of the vase is concerned, the painting of the pipes confuses us a little. When we look at the shape of the pipe bowls, it is an unbalanced product from around 1735. However, the date of the vase must be later. The transparent way in which the decoration is painted and also the foliage on the belly suggest the Louis XVI period, even though the shape of the pipe bowl was completely oval at that time.

Another question mark is where this product was made. The yellow shard with the white tin glaze and the blue painting evoke the word Delft for the layman. The connoisseur, however, immediately observes that it is not a Dutch product, but rather foreign manufacture. That difference is in the shape of the vase, which does not fit in the Dutch shape range. Even the glaze paste is different so is the way of painting. Despite careful analysis it has not been possible to establish a further production site.

It is worth mentioning that French prints from the nineteenth century regularly show the pipe vase. It can appear in a still life of tobacco products and smoking equipment. When the illustrator went wild, we even see burning pipes in the vase. These vases are simply decorative vases whose shape, or decor has no relation to the function. In that respect the "real" pipe vase remains a rare object.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.095

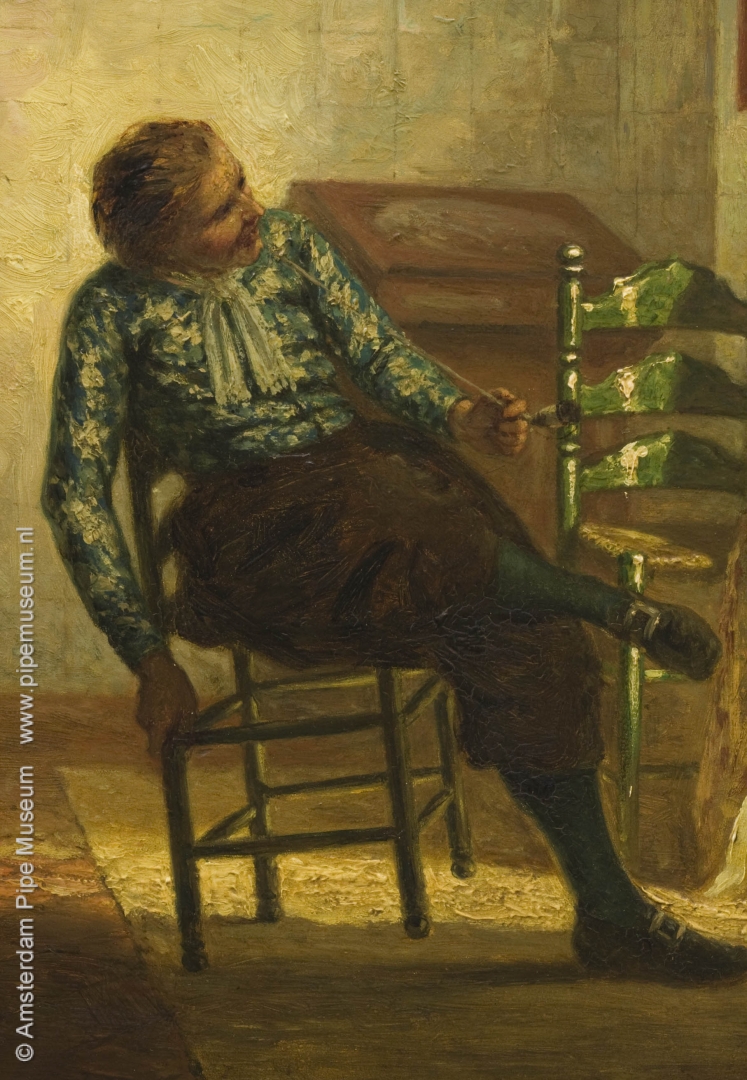

Self-portrait of a smoking lady

In the tobacco literature, the self-portrait of Madame Vigée Le Brun is the most widely published smoker's portrait. Her majestic appearance, with plunging neckline and feathered beret makes an immediate impression. In addition, it is a painting with an unusual theme: a smoking woman who slyly smiles at us from behind her pipe drawer, a clay pipe in the raised right hand. In the period of creation, between 1820 and 1840, smoking for women was not done. Ladies of the stand used snuff.

Not surprising, therefore, that countless publicists chose this portrait to show pipe-smoking in a wider perspective. Alfred Dunhill was the first in 1924 to use the painting as a colour illustration in his standard work. Subsequently the distribution of his book made the portrait known worldwide. Count Corti took over the illustration a few years later and that is how the print also spread in the German-speaking area. After that, copy after copy emerge, as authors tend to do. Not surprisingly, when the fifth centenary of the tobacco was celebrated in Vienna in 1992, this portrait had a central position on the exhibition.

If you want to illustrate smoking in more detail, this painting is eminently suitable. In front of the elegant woman dressed in Scottish fashion and with a fragile clay pipe, there is a box with two compartments on which all kinds of smoking equipment is displayed. We see three short clay pipes, a pipe stopper with an eye, a burning wick, an ashtray and another cup. Behind the pipe box we see two more glasses. It is a smoker's still life in small size.

The painter Elisabeth-Marie Vigée Le Brun listened to the nickname Louise but was known in France as Madame Le Brun. She was born in 1755 and has worked throughout her life as a portraitist. She left a great oeuvre of hundreds of portraits of royal and noble people from almost all of Europe. In France she was a painter for Marie-Antoinette and therefore frequenting the highest circles. Obviously she travelled a lot and visited countless foreign courts where she portrayed an infinite series of high-ranking people. Besides portraits of others, Madame Le Brun also made several self-portraits of which this is the most striking.

How Alfred Dunhill acquired this remarkable portrait is unclear. We know, however, that it was in his possession before 1924. In the years after 1950 this painting hung in the meeting room of Dunhill in Jermyn Street in London. The story goes that in that period the painting would have changed. The woman with her low-cut dress would have disturbed Mary Dunhill, one of the descendants of Alfred Dunhill and member of the board. At her request, the shocking naked bosom would have been camouflaged with a veil with a few bows. Reality is less puritan and less English. When London was bombed in 1940, the shop of Alfred Dunhill got partially destroyed. Afterwards, the portrait had to be restored and it came fresh in colour from the restorer with a few adornments. The refreshed look was a reason for a new judgment. Meanwhile, the years of meetings in clouds of tobacco smoke have brought back the painting to its original yellowed character. In that state it is now in the Amsterdam Pipe Museum.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.079

The wedding pipe in function

Offering a tobacco pipe to the groom on the day of the wedding is a ritual that was well known in the northern half of the Netherlands. This custom has been so important that it is inextricably linked to the Dutch history of the pipe. The tradition is also known because after the wedding the groom's pipe was kept in a wall cupboard or a cardboard box. Once a year, on the day of the wedding, it was taken out and smoked again. As a matter of fact very carefully, because popular believe has it that if the pipe breaks, the marriage would break.

This painting of a traditional wedding with the pipe prominently displayed, was purchased for our collection at the time as an appropriate illustration of that tradition. A representation of the ritual of smoking the groom's pipe is rare, which makes this painting all the more special. It is a piece of folklore that has mostly escaped the attention of the artists. Not surprising, because rural areas simply had fewer painters. Moreover, the heyday of the wedding pipe lies in the nineteenth century, a time when artists found their inspiration in other subjects.

Painter Pieter Willem Sebes is an exception to this. He was born in Harlingen in 1827, where he became interested in painting at an early age. After a few years in The Hague, he developed at the Academy in Antwerp into a classically trained painter of genre scenes. Although Sebes returned to Friesland several times, he mainly stayed in Brussels, Baarn and Amsterdam, where he died in 1906. This work for example, created in 1877, he painted in Brussels. He has never denied his Frisian background; Frisian culture keeps recurring in his work, of which this painting is a striking example. In addition, he was well known as a copyist of old masters, for example, he made historical portraits after originals in foreign museums commissioned by the Rijksmuseum.

The present painting represents a traditional Frisian interior with red tiles on the floor, white tiles against the wall and blue painted China porcelain on the edge of the mantelpiece. The centerpiece is the bridal couple in Hindeloper costume, the woman in her chintz jacket, the man behind her smoking from a flower decorated groom's pipe with a silver pipe cap. An elderly woman sits in the shade to the right, from behind her spinning wheel she toasts the couple. The painter seems to imply that she represents the period after the wedding. To the left of the center, a boy is rocking in a turned chair. He also smokes a long pipe and symbolizes the unbounded freedom, the time before marriage.

The scene is characteristic for a disappearing local culture with which the painter Sebes was deeply concerned. It is with good reason that the conservative themes from the old Frisian culture recur in his work again and again. Especially the decline of the Frisian traditional costume was very dear to him. That is why he depicted the Hindeloper costume very accurately here, including the use of the groom's pipe.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 10.063

Business card of a tobacco factory

Only the most important eighteenth-century tobacco manufacturers used a business card to advertise their trade. Sometimes a tobacco packaging vignette printed on better quality paper will be used, but in a special case the card is designed. In that case the whole process of making was done with grater care: the paper is of better quality and the detailing of the image is more refined. After all, a business card only has to be made in a limited edition, something that certainly does not apply to the tobacco wrapper that is printed at hundreds or thousands.

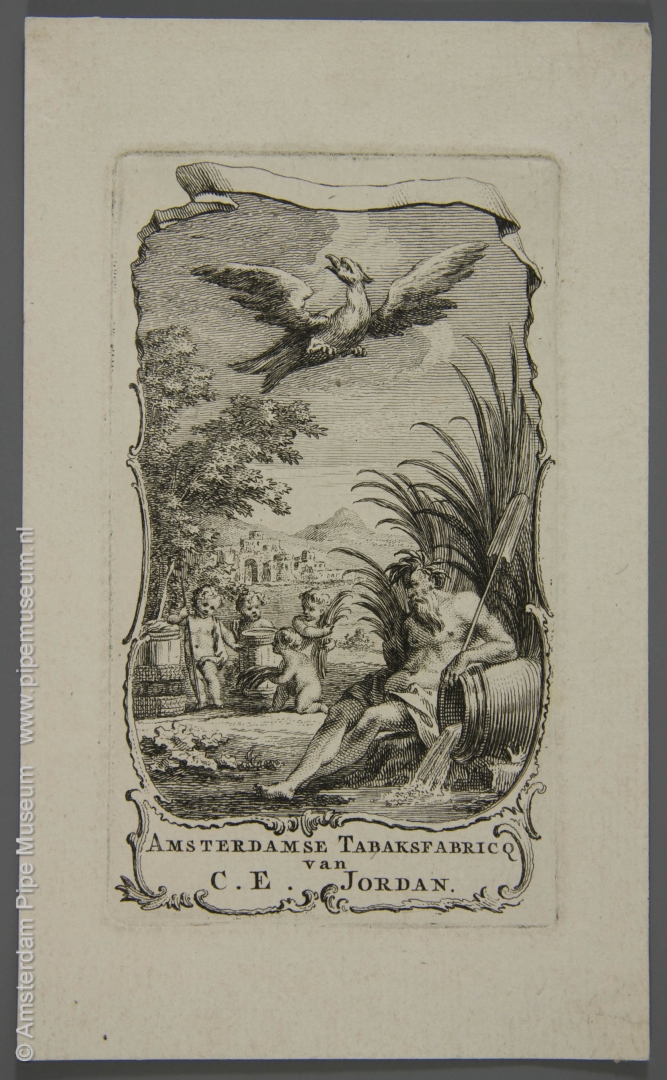

One of the most beautiful business cards comes from the Amsterdam tobacco manufacturer C.E. Jordan. He had his name card executed in unexpectedly large size. The height is more than twelve centimetres, the width exceeds seven. It was made in the technique of the copper engraving, so the image was engraved in negative in a copper plate and then printed. The finesse of the illustration proves that a large edition was not possible. In this generous size, the engraver, whom we can rightly qualify as an artist, has made a beautiful composition in which all kinds of elements have been brought together.

A contoured edge with rocailles is used as a frame, characterized by elements of the asymmetrical Louis XV style. They point to a date in the years 1750 or 1760. At the top in the air an eagle flies, the bottom half shows a so-called scenic landscape. To the far right in the foreground is a sitting Neptune, represented as a river god. His left arm rests on a barrel as the source of a creek or brook, an oar sticks upwards. Such figures are called a repoussoir, a pictorial element strongly in the foreground that reinforces the depth effect of the total image. On the middle left, four putti are busy with tobacco leaves, two tobacco barrels and a half-opened canaster basket. They are the only reference to the tobacco business in the scene.

The background shows a ruin and some mountains that make the landscape explicitly un-Dutch. For a tobacco brand you would rather expect an American plantation here. As we already discovered, the only reference to the trade in the picture are the tobacco barrels and the basket, the other symbols have a different meaning. Enlightening is the text below the plate, where we read "AMSTERDAMSE TABAKSFABRICQ VAN C.E. JORDAN" (Amsterdam tobacco factory of C.E. Jordan). The producer identifies himself with that text.

Although beautifully designed and carefully printed, with our contemporary eyes for advertising, we are a bit surprised at this object. A name card without an address does not seem really useful and the reference to the product offered is very thin. Only those who search well can get the clue. Yet this print is of such a high artistic level that the name card of Jordan is one of the most special business cards in the entire tobacco industry.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 25.003

Women at work

Old photographs are an important testimony of the factory and the working conditions in the companies of the past. Unfortunately, only seldom was there reason to record everyday life with all these grubby workers. That is why such photographic recordings are scarce. It is remarkable that in 1908 the manufacturer Goedewaagen had a series of seven photographs of the manufacturing process in his factory made. Of this series, this photo is the most interesting. It was taken at the so-called machine workshop, a department that only existed for a short time.

Around 1895 there was a sudden yet substantial demand for simple short stemmed clay pipes for export. Business offices in England and Ireland were able to sell immense batches, for example to smokers in West Africa and in America. There was a fierce competition to get such orders among the factories in the various production centres all over Europe. It was not a matter of a few gross, but an export order sometimes included hundreds of boxes, each with a volume of two or three gross.

In Gouda the manufacturer Goedewaagen managed to make the right contacts to get these orders. At that moment, however, he got into trouble. Not enough men were available for press moulding the clay pipes. It was therefore necessary to partly mechanize the production so that women could be deployed. Swiftly a machine department was set up where the pipe making was carried out with the help of steam power and thanks to this mechanization, deliveries could be realized.

This photo shows that department, which was built in 1895. The space was located in the attic of the old pipe factory on the Raam in Gouda. The photo clearly shows the wooden ceiling where leather belts operate the machine presses facilities. Thanks to the steam power, the pipe making, traditionally old men's work, could now be performed by women. They only had to put a pre-rolled basic shape pipe in the mould, the machine provided the actual press force and the woman's hand came back to remove the pressed pipe.

No matter how easily this work sounds, the work in the attic will not have been very pleasant. The machines made a deafening sound while there was a dank air of dried clay and oil. Factory director Aart Goedewaagen, who gave me this picture in the 1970s, spoke of a miserable working climate. He was ashamed of that situation. Unsurprisingly, this machine factory did not exist for long. A year after this photo was taken, the pipe factory moved to a fresh and spacious factory building just outside the city centre, and the women's department was disbanded on that occasion. They went back to the noble handwork and became involved again in finishing or polishing the clay pipes. Incidentally, at the same time, the commercial value of the cheap export pipe decreased due to competition from other production centres and a change in the smoking behaviour of the consumer.

The photo series, of which this is the most striking image, was made by photo studio W.J. van Zanen in Gouda. Precious as they were at the time they are stuck on cardboard and carry the embossed signature of the photographer in the lower left corner, just as a statement of a proud artist on a painting. Fascinating with this photograph is the silent image of working women that you expect every moment to come alive again.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 235c

Fanlight of the tobacco trade

This architectural piece of more than a meter wide is known as a transom light or fanlight. It is also named carved window frame because the whole decoration is carved from wood, originally with glass behind it. It was mounted above the front door of an Amsterdam canal house, in such a way that sunlight could shine through the glass into the hallway. At the same time, the original owner emphatically advertised his business, in this case the tobacco trade. The central oval with pearl frame contains a painting on metal of a scene with three full-length blackamoors. They are standing on the coast of a tropical country, as evidenced by the palm tree on the right, on the left the outline of a sailing ship at sea can be seen. The person on the left points to a barrel of tobacco next to him, the one in the middle has a bow in his hand, the figure on the right is standing next to a chest of merchandise and is smoking a long pipe.

However, the most obvious reference to the tobacco trade can be found on the bottom line of the window. There is a variety of tobacco packages on display: a large tobacco barrel, a so-called ox head measuring 230-liter in which tobacco from Virginia was supplied. Such barrels often weighed more than fifty kilos. The ornate lidded jar with inscription "RAPPE" is obvious for snuff. We no longer know the spun tobacco on the roll, but it was most common in the shops since the eighteenth century. Three stacked and sealed boxes contain letter tobacco, a packaging for the most expensive and exclusive varieties. The most characteristic packaging has been called karot tobacco, a torpedo-shaped roll of tobacco bound together in palm leaf with rattan bands. There are three on top of each other, with a stake of a tobacco plant behind it. In this form tobacco came from South America, for example Venezuela.

You can assume that the central presentation is related to the tobacco brand of the store. Several options are open: De Drie Marylanders (The Three Marylanders) or Indians, that ties in with the plumage of the centre figure. Another option is De Drie Morianen (The Three Blackamoors), African slaves as indicated in the dark skin color and the frizzy hair. Another well-known tobacco brand to which, according to a vague tradition, this fanlight refers is that of De Drie Koningen (The Three Kings), but this brand scores less because their crowns are missing. Incidentally, all three tobacco brands are known from Amsterdam shops, although that will not be exclusive because many brands were copied elsewhere.

Such eye-catching carved frames intended to advertise a private trade were usually painted and the same happened here. The paint protected the woodwork but also gave an extra accent to the advertising. Old green is used, with brown and lighter green on the attributes placed on the bottom line. The type of paint used is the so-called casein paint, a natural paint with a nice matt result.

Dating is not easy. Much of such carving was not done according to the latest fashion because it had to last a long time and be understandable for every customer. The decorative carving around the central painting gives the best clue here. The draped curtains on both sides and especially the imposing circle ribbon bow in the middle are typical Louis XVI elements. Meaning that this window is made between 1770 and 1790. The popular rococo style with its asymmetrical ornaments is already over by then. A later dating should mean that we see Empire elements, which is not the case. Because it is unknown where this beautiful carved window adorned the facade, we cannot say anything about the period of use, but it may have hung above the door for several generations.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.098

Sample box of Lehman

In our time when all tobacco products come from factories, we know nothing but packaged goods. This is advantageous because the product stays at the correct humidity and thus retains its aroma. Moreover, tobacco has a uniform taste due to the strong standardization. That was different in the past. The tobacconist largely prepared his products himself, although he also bought ready-made merchandise from itinerant sellers. An extremely rare object of such a representative in packaged tobacco has been preserved.

It is a travel case with samples specially made to show tobacco products to retailers. It is an object of great exclusivity that is clearly meant to impress. The box has a rectangular shape with a maximum length of over thirty centimeters. It opens into two equal halves, each of which in turn opens again. This creates a long strip of four connected boxes, all covered with plane flaps edged with rolled gold. Once unfolded, the whole takes up a length of one meter and twenty centimeters. As a sales representative, you can fill the full length of the counter at a tobacco shop, for an overwhelming impression.

A special feature of the cassette is the extremely chic materials and fine execution. The outside is made of dark red morocco leather with clasps in gold color. When unfolded, you see four large lithographed images of elegant ladies who have little to do with the tobacco product, but demand immediate attention. Each facet of the assortment is housed under these flaps. This range falls into three main groups: tobacco, snuff and cigars. The tobacco range, packed in blue boxes, consists of samples of the common varieties of the manufacturer. When we open this box, we are amazed to see the wide cuts that were current at the time and also the pure form in which the tobacco was sold. It indicates that the cassette dates from the time when aromatic pipe tobacco was not yet common, nor were the blends.

More important is the snuff. This one is also packed in small square boxes, now pink in color and luckily most boxes are still filled. Although no longer aromatic because the scent has evaporated over time, the method of grinding is still visible. In addition to fine blends, we see strange coarse varieties that don't look very appetizing. It is clear that the fashion of snuff has also changed completely.

Finally, there are the cigars, the modern smokers’ favourites at the time of the cassette. No examples of these have been preserved. Apparently they have been smoked, that is the fate of a cigar. The size of the boxes tells us that in Lehmann's time the cigar did not exceed twelve centimeters. Today no-one would think that’s a serious cigar.

Interestingly, the manufacturer affixed brand labels of the types he supplied to the inside lids of the travel case. This gives us an impression of brand names that were in demand. Those brand names betray English and French imports, in addition to cigars from Havana and other distant places. This degree of exclusivity proves that Lehmanns’ representatives only supplied the best of the best. In addition, the brands show that in this time tobacco consumption was a great culture, imbued with a high degree of luxury and exclusivity.

The owner of this beautiful suitcase was an man named Wolf Lehmann from Amsterdam, a shopkeeper in the Warmoesstraat. In addition to the exclusive brands, Lehmann sold standard tobacco for which he used the local Muiderpoort brand. That tobacco was cut in his shop. As evidenced by the lithographs on the lids that are dated 1832 and 1833, the case dates from the mid-1830s. The French origin of the lithos may indicate that the cassette could also have been made there. Given its fragile nature, this cassette was only taken on the road when visiting serious customers.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.835

© Don Duco, Amsterdam Pipe Museum, 2020.