Highlights of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Hoogtepunten uit het Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Publication Year:

2020

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

A tubular Indian pipe

The pipe shown here is primitive in design and finish, but beautiful in its simplicity. It is the most obvious pipe shape: the tube shape, which is referred to by scholars as tubular. The pipe is just over fifteen centimetres long and is made of brown-black steatite with a slight hint of green. In terms of shape, this pipe is mainly cylindrical but narrows at both ends resulting in a slight oval shape. Around the bowl opening an inconspicuous trim can be seen, referred to as raised ring in professional circles. The stem end is slightly taping and nicely rounded. The final edge of this mouthpiece is somewhat uneven and a bit worn. The pipe has obvious traces of use, but at the same time it is excavated as an archaeological object in great condition.

Although the tube shape gives the impression of being made on a primitive lathe, that is certainly not the case. In the early period, the Indians were still working completely manually. The object was hollowed out with a flint on a stick as a drill. The stem is drilled from one side of the pipe, of course with a rather thin drill, then the bowl is created from the other side. By manually rotating the drill, the shaft is not purely cylindrical and straight, but shows rings with a slight gradient. The outside rather seems to be scraped and polished to the desired shape out of hand, including the lining around the bowl opening. In short, it is a completely manually made object.

After drilling, the pipe has been extensively finished. Internally, the bowl part has been further hollowed out in order to get rid of the rings of the drilling and to make the bowl more spacious. On the outside the pipe has been smoothed, although the surface still shows numerous scratch and grinding marks that testify to working with primitive tools. Apparently, at the time a new pipe was characterized by a web of such grinding tracks. In the course of use, these scratches were washed away until a nicer, smooth surface was obtained, naturally with a warm patina of frequent handling. Internally, half of the pipe length consists of the bowl intended to be filled with tobacco, so it is about 7 centimetres deep. The bowl and stem sections cannot be distinguished on the outside of the pipe.

The tubular served a way of smoking that has been common practice for centuries. The pipe was filled with pulverized tobacco and smoked in a lying position. With the Indian tribes this has become a use that even contributed to the ceremonial meaning of pipe smoking. An additional component was part of this pipe, which is understandably lost. However unexpected, the native Central-American Indians have mounted this bowl on a hollow stem or on a bird bone. With the aid of bitumen, the two parts were tightly connected. That joining is still visible in the stem section where traces of adhesive are still present despite the age.

It is hard to put a date on this object. The period of use of such pipes runs from 500 BC until the turn of the last century, since the tubular pipe has remained in use in many Indian cultures until shortly after 1900. Our example does not seem to be a really early specimen, nor a recent one, but rather a regular product from the time that the manufacture was already somewhat standardized. To be on the safe side, we can definitively put a period dating between 500 and 1500 on this specimen, probably more precisely between 800 and 1200.

Literatuur: Don Duco, Alfred Dunhill's fascinatie voor de tubular pipe, Amsterdam, 2007.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.084

Mississippi duck

This swimming duck is a beautiful sculpture from the prehistoric times of America. It belongs to the Mississippi culture and was found long before World War II in Sevier County in the state of Tennessee, midway between the Great Lakes and Florida. With its length of almost twenty centimeters, it is a monumental object. This authoritative monolith can be extended at the back of the duck with a hollow branch or piece of reed to create a usable pipe. It is not an ordinary smoking pipe, it is rather a ceremonial object.

Mississippi culture is an early Native American culture broadly known through excavations of their burial mounds that earned them the name Mound builders. As with all pre-Columbian periods, there are no written sources, so much remains to be discovered. We're talking about the Late Woodlands Period, in which Mississippi culture dates back to between 800 and 1400. The area stretched from the Midwestern to Southern States. The sculpted pipe shown here dates from the heyday of this culture between 1000 and 1300. The depiction of a swimming duck is popular in this culture, which is logical because the Mississippi basin is overcrowded with ducks every spring and autumn. In addition to fishing and foraging for berries, the birds have been part of the livelihood for centuries. Characteristic for all Indian tribes in America is that they live in harmony with nature. The duck has become an important symbolic animal for them.

The pipe bowl shows a duck swimming away from the smoker, the bowl with a colossal thick wall is placed behind the head of the animal. The body is fairly cubic with wings on the stem with recessed flight feathers, on the underside we see a leg with webbed feet in lighter relief. The eyes are hollowed out and were originally inlaid with a different type of stone or mother of pearl.

In our example, a dark green steatite is used, a type of stone that is relatively easy to work. Most such duck pipes are made from it. The design is beautifully serene and stately depicted. Note the sturdy appearance with stylized shapes and experience how the lines that make up the representation blend together. Yet it is not a unique creation, but an object that fits in a rite and was therefore made over and over again. The depiction does not change, but the stylized form characteristics do. This pipe is an excellent and representative example with regard to the type of stone used, size and design. A considerable number of such pipes have become known from the more than two hundred excavations in the Mississippi cultural area. Yet every pipe is fascinating because the design is always different. It is certainly not a serial product, but always an original new creation that has been made with great care and dedication.

Although technically functional, the object is too heavy and massive to simply smoke. For pleasure, a pipe smoker will not choose such a piece of stone. However, the object played a role in burial traditions, because these pipes are always found in the enormous burial mounds that can have a height of up to eighteen meters. Most such pipe finds have been made in Ohio. Other examples have emerged in northern Kentucky, eastern Indiana, but similar specimens have even been excavated in Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana and North Carolina. That says a lot about the long period for which the duck motif has been popular and which led to its wide distribution.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.524

Steatite bird

The tobacco pipe of the American Indians comes in a great variety. Unsurprisingly, the culture is ancient and each local tribe had their own rites and customs for making pipes. A fine example of such an Indian tobacco pipe is shown here. It is a steatite pipe with a slightly funnel-shaped bowl that stands on a four-sided figural stem that continues after the bowl. While the bowl is just an unadorned, slightly conical cylinder, the stem on the other hand bears witness to a special design. It shows a bird, the head and beak off the smoker, the tail is the end of the stem, the wings on both sides of the bowl base are both filed out of the stone and incised. The legs, located on the underside halfway the stem, also in relief, are cut out of the stone. Although the first thought would be that it is an eagle, it is more likely that a hawk or a falcon is depicted. However, the stylization of the object does not make this discussion very meaningful. Better to enjoy the highly stylized and yet recognizable style.

This product expresses the Indian's love for the depiction of animals. In addition, the pipe is a wonderful example of styling shapes. Working in stone is not the easiest, especially when we consider that the Indians could not work metal and thus had no metal tools until the arrival of Europeans. Yet they succeeded in making very successful sculptures by grinding and drilling. Perhaps precisely because of the slow manufacturing process, they managed to achieve great expressiveness with minimal details. We see this in this bird, which, although highly stylized, is nevertheless convincingly portrayed.

Sources report that this tobacco pipe have been found in Coffee County, Tennesee, but collector Petri who cherished the item in his collection for decades, assumes production in North Carolina. E.K. Petri may be considered a connoisseur, although it is always good to leave room for doubt. In the 1940's Petri was president of the North American Indian Relic Collectors Association. He wrote about this particular object that he owned at the time: Middle Woodland Period, designation for a prehistoric culture in a wide region south of the great lakes from 200 BC to 500 in Domino. He even allows for an earlier dating to the Adena culture, in the Early Woodland Period from 800 BC to 100 AD. With such unique pieces, it is clear that their identification is a tricky matter and that the last word has not yet been said.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that this pipe is said to be originally embellished with mother-of-pearl, ivory and precious metals. The fact that ivory appears in the list of materials makes this claim extremely doubtful, unless it concerns walrus ivory. Regardless, in its simplicity of design, this tobacco pipe is a worthy piece of stone sculpture that needs no frills to be precious.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.525

The peace pipe of the Indians

The Indian tribes of the Great Plains, the prairie area east of the Rocky Mountains used pipes in a specific style. We are talking about pipes that are officially called calumet but are generally known as peace pipe. For the latter, the term ceremonial pipe would be more suitable, because besides the peace pipe a war pipe was also used. Characteristic of the pipes is the red stone, called catlinite in the particular, so-called calumet shape.

The beautiful red stone for these pipes is found in layers that can easily be sawn away from the rocks. The colour can vary greatly, sometimes it is completely plain, sometimes slightly speckled. For the red version the name Minnesota pipestone is also used. As a commodity, this stone is sold to all areas. Because the type of stone is relatively soft, it can easily be processed with simple tools, which applies to drilling, grinding and polishing. A positive feature is also that it resists heat well, through use it gets a beautiful patina.

Typical for the traditional Plains pipe is the high cylindrical upright bowl which is usually slightly shorter than the stem part into which the stem is later inserted. This stem continues beyond the bowl, getting a little slimmer and often ends in a nicely bevelled point. Because of this characteristic silhouette, such pipes are simply designated T-shaped, corresponding to the shape of an inverted letter T.

Both quality and age are shown in the way the pipe is finished. Initially it is only cut and polished resulting in a smooth surface. In the historical period, more and more metal tools are used, leaving mechanical traces on the object. We see that especially in the drilling of the bowl and stem opening.

The stone pipe bowls are originally mounted with a long straight wooden stem with a flattened shape. Sometimes such a stem is decorated with some carving, but usually it is smooth. At the end this stem is decorated with the so-called quill-work, braided leather bands in different colours. Often this braid has patterns, as with the pipe of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum with two arrowheads in a red field around a four-pointed star. On the underside, even a text has been made in the quill-work. The mouthpiece ends in a point adorned with a band with colourful bird feathers. As an extra decoration a yellow silk ribbon with hanging ribands is added.

Interesting is the label that is glued on the stem of this pipe. Within a red border we read "M.I.McCREIGHT TCHANTA-TANWA CEREMONY OR ADOPTION AS CHIEF '08". It refers to a certain Israel McCreight who received the pipe as a gift when he was elected as Chief. That must have been in June 1908 in DuBois, Pennsylvania. At the time, the pipe had been in use for some time, and that goes well with a gift to a Chief who was also an expert on Native American cultures. Eventually this object ended in the Tobacco Museum of Vienna and when that collection was auctioned the pipe moved to Amsterdam.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.847

Sioux club

This item is a rare combination between a head knokker and a tobacco pipe. It is an object found in many cultures, including Africa and Oceania. In those regions it is called a club, a more general indication is knobstick. You can think of them as a bat to keep away or even kill small game. In addition, the function as a tobacco pipe has been added - a rarity - by drilling a pipe bowl in the stone and piercing the stem. Finally, as a third function it is a status object, so not primarily intended as a utility, but mainly to underline the status of the owner.

The whipping stone and therefore also the pipe bowl is made of reddish catlinite, on the left side it is somewhat ruddy veined as a result of the thin layers in which catlinite is found. The heavy head has a barrel-shape with a flat top with a wide bowl opening, the bottom is also flat. The pipe bowl shows in relief all around a snake with its head at the tip of the tail, the tongue protruding from its mouth. The decoration is certainly not functional, but so is the massive shape of the club that can easily give a deadly blow. That is the primary function of the object.

The stem of the pipe is set on the side halfway to the bowl height, so that the hammer head has a good balance. It is made from a willow branch, and when that wood is fresh, the stem is tough and flexible enough not to break. Only when the wood ages, the stem becomes vulnerable. Initially, the club has a long stem that swings well when used by riders. Later the stem becomes shorter, as with this object. The stem is covered with raw hide that has been sewn on, a piece of skin around the bowl is sewn back on the stem and must ensure that the stone cannot shoot off the handle. The head knokker is characteristic for the Sioux Indians of the Northern Great Plains and is used by hunters to kill animals. In this case, a rare combination has been devised with the addition of a peaceful instrument such as a tobacco pipe.

Unique objects like this rarely change hands. This also applies to this pipe that has been in John Adler's collection in Chelmsford for 40 years. Adler obtained the pipe from another English collector before 1980, after the pipe naturally had its own history in the US. This is also a guarantee for authenticity. This old English collection was put up for auction in Colchester in 2017. Despite the great international interest at that auction, it remains surprising and unexpected that such an object was hardly recognized by anyone. It is the rarity that has ensured that opponents in the auction were not convinced of the originality of this item. This made it easier for our museum to be succesful with the purchase.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.883

The American Indian tomahawk

An Indian pipe that really appeals to the imagination is the tomahawk. Although the object looks like an ax, it is not. It is a tobacco pipe but combined with a throwing ax or melee weapon. It is especially surprising that this characteristic Indian pipe is not a native invention but was devised by the Europeans to trade with the North American Indians. The American-British smiths worked the iron, but the native people determined the design whereby the pipe bowl is often the same as the stone pipe bowls of the Micmac Indians. The tomahawk quickly developed into a prestige object for chieftains in keeping with the American tradition of smoking a pipe during war and peace negotiations. Not surprisingly, these pipes were used by the chieftains as the ultimate status object. When we see nineteenth century portraits of local chiefs, the tomahawk is often worn as a symbol of power, much like a king's regalia.

The combination pipe bowl and ax remains odd, but we should not take the ax function too seriously. Certainly not when the pipe is made of a vulnerable type of stone. However, the best tomahawks are forged from iron or cast from brass, combinations of both materials also occur. The decoration is usually limited to the blade of the axe. Sometimes motifs are cut into it, such as a star. In our case, we see an oblique heart, surrounded by a circle of dots. Sometimes the metal is provided with inlays in silver.

The stem of the tomahawk is made of hardwood and drilled over the full length. The connection from this stem to the pipe bowl is made by drilling a vertical hole. The end piece is then closed with a wooden plug or a metal pin. By removing that pin, the pipe can be cleaned easily. A strip of leather is placed between the ax and the stem so as not to create false air when smoking. The stem itself is often decorated with brass nails, here for example placed in simple rectangles. A pierce through the stem at the stem end is used for hanging a decoration, of cloth, leather or some feathers. In the older specimens such as this tomahawk, that decoration has long been lost.

The oldest tomahawks were made by the English, French and Canadians. Later, this mainly happened locally in the American colonies, but always by the settlers. Native American chieftains could acquire a tomahawk by trading hides or other goods. The story goes that a tomahawk had the equivalent value of a pile of hides as high as the length of the stem.

The example shown here belongs to the earlier type and is a fully functioning pipe, although in principle it could also be used as a throwing ax or a melee weapon. The pipe bowl at the top seems round but is slightly four-sided and is profiled with two circumferential and a constricted band. The stem of the pipe has a diamond-shaped cross-section and is, of course, completely drilled. Also with this pipe the leather between the metal and the wood is not missing. In short, a full-fledged pipe, although the balance is not too good because of the forged axe. For a status item, you accept that.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.883

Raven pipe of the Canadian west coast

This tobacco pipe has a figural bowl, the start for the stem, a simple hollow twig, is drilled into the back. The bowl is shaped as a sitting raven in a stylized design, with large, almond-shaped eyes and a crooked beak. On both sides of the torso it holds its stylized wings against the body, continuing along the back, the legs are clenched. Finally, the animal has a short tail. It is a full sculpture with a strongly cubic shape that gives the bird, despite its size of only nine centimeters, a monumental appearance.

The raven is a mythical bird that is at the origin of both the Haida and the Tlingit, two peoples in south Alaska and the northwest of the Canadian province of British Columbia. According to local myths the raven created humanity and civilization in those regions. Moreover, it is a symbol for several clans, somewhat comparable with the heraldic Dutch lion. That is why the raven appears in sculptures, both in wood and stone, often as decorative top of the well-known totem poles. Since it is mainly the Haida who work in stone, this pipe seems to have been made by that people. However, there are some doubts.

In general, in the Haida carving tradition, more emphasis is put on the head with the large beak. The raven in complete portrayal of the animal is, by comparison, more common in the Tlingit tribe. More specific we can relate this object to a clan that lives along the Chilkat River that originates in the glacier of the same name in Alaska. Hence the tribe is called the Chilkat Qwan, also phonetically written by them as Jilkaat Kwaan. Their habitat is particularly rich in salmon, which in turn attracts other animals such as the bear and bald eagle. These animals are not only important for livelihoods, but are firmly rooted in local mythology and traditions. Yet the raven as a mythical bird remains the most important animal for them too. We therefore attribute this pipe to this Chilkat Qwan, within the Tlingit culture.

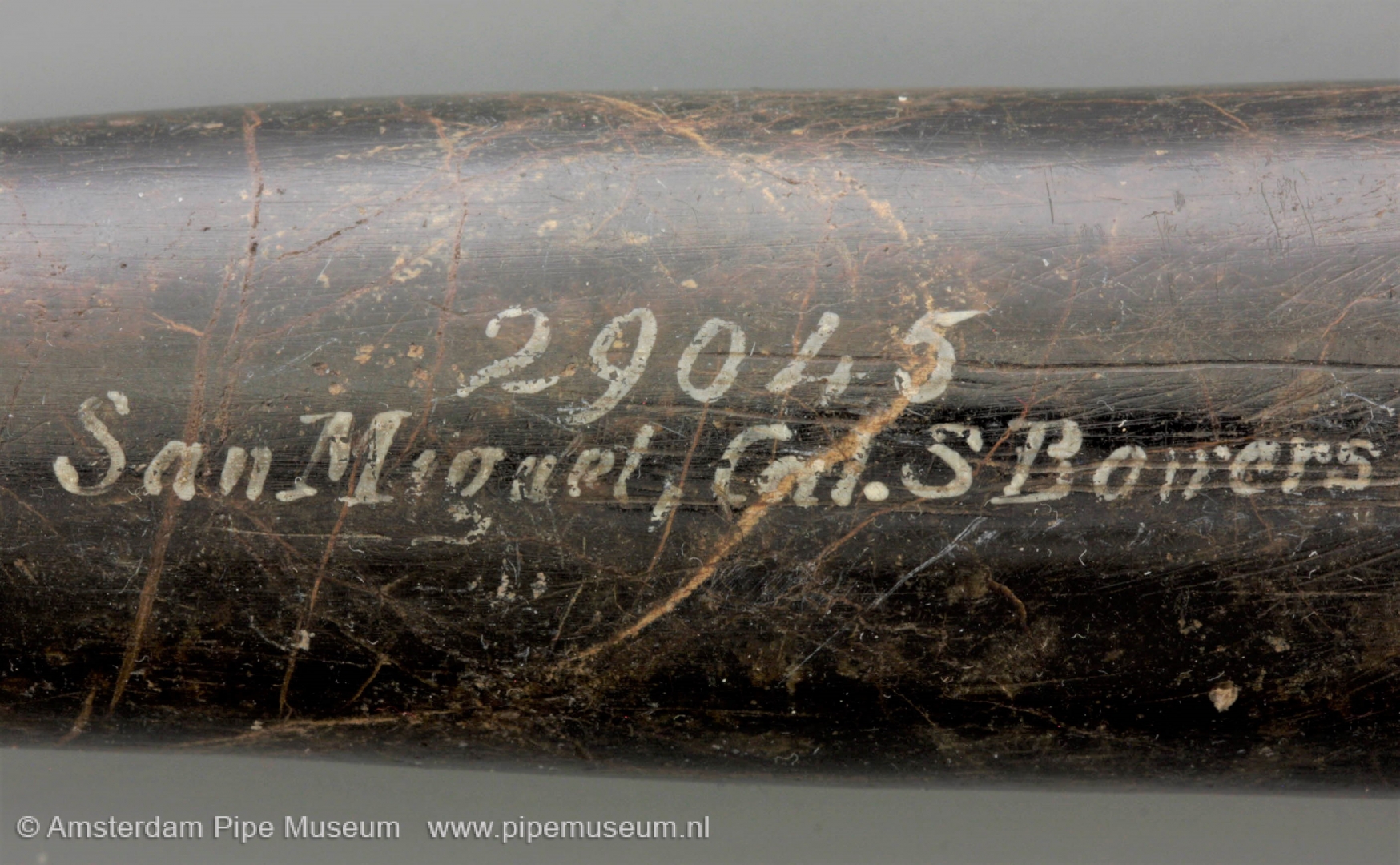

We can be sure that it is a genuine tribal object with a good age. An old museum number is written in red ink on the underside of the bird's leg. That number proofs the long-term preservation in a museum environment. In the United States, the museum status is not a guarantee of eternal incarceration. Museum objects come onto the market more often than might be sensible. Our museum owes this special object to this typically American custom of selling out, now cherished on another continent as an iconic symbol of a nearly extinct culture. A very annoying aspect of the antique trade is that the pedigree of objects is never disclosed, so the museum that once held this piece is not known.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.759

Tlingit rifle butt

This almost cubist pipe bowl is one of the most special ones in the collection of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum. It is a ceremonial pipe that was smoked at funerals. The piece of wood of this pipe bowl has found its second use, previously it was part of a rifle butt. That weapon was captured from the English colonists by the Tlingit from Akaska and was given a new function. In other words, a trophy that was subsequently carved in an exceptionally expressive way into a ceremonial utensil that was of great value to this Indian tribe.

The Tlingit, like their neighboring tribe in the south the Haida, were a people of fishermen at sea and at home foresters and woodcarvers. Russian traders forced them to hunt seals for fur. From 1785 onwards, the English also appeared on the scene. So the local Indian tribe faced plenty of intruders. Despite the supremacy of firearms, especially by the English, a rifle will have been captured once in a while. There is nothing better than to demolish the opponent's weapon and thus celebrate the victory.

In its second use the rifle butt has become a tobacco pipe. The original cross-section of the butt is clearly visible, especially on the short side. It is drilled in at the top to provide space for a cylindrical brass bowl, which is secured with a piece of textile. This substance secures the bowl and prevents false draft. The edge of the bowl opening has been turned down for the sake of strength. The pipe bowl thus resembles a chimney that protrudes above the pipe, one of the most characteristic design aspects of the Tlingit pipes. The front end of the rifle butt is pierced for a separate stem. A simple pierced wooden stick was placed in it as a mouthpiece to smoke the pipe. The pipe is handy but substantial. The bowl length measures thirteen centimeters.

The flat sides of the log are cut in a not too deep, but clear relief. The powerful design forms the artistic apotheosis. A fish head dominates on either side, created by bringing together a few simple but effective elements: almond-shaped eyes, a mouth with teeth and gills at the stem side. A fin protrudes along the top, as well as behind a large gill at the bottom. The places where the screw holes of the rifle plate used to be are still visible, which are concealed at the end of the object with wooden plugs.

Created in the 1820s or 1830s, this object was owned by the tribe for at least a generation. This was followed by deaccessioning, presumably through sale to a traveler. That is where the nomadic life begins, of which we can only trace the last owners. Ultimately, the pipe was delivered to the Drouot auction house in Paris in 2013. The following lyrical description dates back to that episode in the auction catalogue: "See how the pure form of the animal resonates in the most bizarre creations of the world's greatest surrealists. The simple lines speak for themselves but together create a consistent image. The deadly character of the former weapon is surpassed by the elegance of its curves. The beautiful patina testifies to long use not only as a rifle butt but also as a tobacco pipe ".

Although Tlingit pipes are always easily recognized, especially by their metal chimney bowl, the design is so creative that the variation seems endless. Usually one of the locally occurring animals is the main motif. The processing of an animal head within the scope of the rifle butt is unparalleled and clearly indicates that the wood of the rifle had to remain recognizable to the maker. An example of intercultural exchange from long before the time when someone invented this word.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.207

Head of a salmon

In many places around the world, the tobacco pipe is an object of high status and significance in the rites and customs of the local traditional culture. That certainly applies to the tobacco pipes of the Tlingit, an Indian tribe that lives along the south coast of Alaska where it continues into the northern part of Canada. It is a strip of land on the Pacific Ocean where the people live from fishing and hunting in the forest area on the mainland. Many Tlingit pipes played a role at funerals. At meetings they were smoked, usually by handing them around in the circle. After the ceremony, then they were stored away again and kept until a new occasion arose.

Because the Tlingit is a very independent people with few contacts with neigboring tribes in the area, they use a specific type of tobacco pipe that shows hardly any affinity with the smoking instruments of others. Local wood is used as a material. In the bowl, that wood is doubled with metal that, very typically, protrudes above the wood as a kind of chimney. The top edge is often turned over so that it is a bit stronger and less sharp. The wooden pipe bowl has a carved decoration with a short stem attachment. When in use, this truncated stem is extended with a simple straight stem to draw in the smoke.

This pipe depicts an animal head that initially resembles an eagle, but that is a deception. In fact the head of a salmon is represented, as it were torn off the fish just behind the gills, the red blood dripping from it. Reason that one could easily take this animal for a bird is due to the strongly overhanging upper lip, a characteristic of the very old salmon. As a fishing people, the Tlingit of course knew all about the salmon in all its manifestations.

With a length of more than seventeen centimeters, this is a hefty pipe bowl. The depiction is highly stylized, but not to be missed due to the sharp silhouette. A few lines give substance to this powerful depiction. The characteristic Indian painting in the colors black with accents in red and white complete the fish. The pigments in the paint come from nature. Finally, the animal's nostrils are marked with two drilled holes in which we find remains of bird feathers. They recall the ceremonial function of the object, that had an extraordinarily striking silhouette with its two long feathers.

In addition to this salmon head, there are Tlingit pipes with all kinds of animal figures, such as a toad, eagle and bear. Not surprising for a people with traditionally animistic beliefs. They provide daily utensils with images that give it a spiritual power, certainly applicable to a funerary pipe like this one. We don't really know what the daily pipe of this people has looked like. Undoubtedly they were small handy smoking implements without too much frills. This ceremonial object was made between 1840 and 1850 and was preserved within the tribe for quite some time. Ultimately it exchanged its ritual function for a cultural-historical one in the museum.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 23.89

Walrus ivory pipe with engraving

There are no Indians living in the Arctic region along the west coast from Canada to Alaska. It is the territory of the Inuit, a people with a limited material culture. They fish and hunt for livelihood, where it is an important tradition to use really all of the hunted animal, be it for food, clothing, or whatever. Their household effects and consumer goods are therefore the result of those activities. Not surprising that they have little luxury. Even tobacco for smoking is scarce, it is obtained by trading hunting products. When the Eskimo smoke, they use pipes with a small bowl whose smoke is deeply inhaled to get into the desired state.

The finest material imaginable for their tobacco pipes is walrus ivory. This dental material has a attractive color, is impenetrable and can be finished beautifully smooth. The disadvantage is that it is not easy to carve. Naturally, the shape of the tobacco pipe is related to the walrus tooth, so in a slight bend. This gives the pipe a specific shape with a slightly upwardly curved stem that narrows towards the mouthpiece. Of course, the latter has to do with the point where walrus tooth ends. The stem is flattened on multiple sides to a six or octagonal diameter. The Inuit engraves his decoration on these surfaces, and highlights the lines with black dye. The actual pipe bowl at the end on this stem, in this case of dental material as well, has a funnel shape. Given the tobacco scarcity, the bowls of the Inuit pipes are small.

The tobacco pipe depicted here is characteristic of the Inuit. The bowl is modest and somewhat uneven on the outside, due to the irregular tooth material. Very specific is that the stem decoration has not been applied on all surfaces, but that panels on both sides and along the top and bottom edges have remained smooth. This enhances the rhythmic effect of the pipe and makes the stem appear longer. As decoration it is customary to apply line drawings in the surface. The variation therein is endless. We know Inuit in action in the form of small figures who hunt, ride a sleigh or sit in front of their igloo, sometimes even depicted smoking. Obviously interspersed with polar bears and seals. These are scenes that mainly appeal to tourists in that region.

For the people themselves, there is a certain hierarchy in the decoration. A pipe for personal use is more often abstractly decorated, while an object for sale to travelers or tourists is more likely to be provided with popular images that are more salable in the souvenir trade. The pipe depicted here with a geometric pattern is therefore intended for personal use. Above and below the plano track this has an unexpected rhythm of diagonal bars, tending alternately to the left and right which creates a somewhat psychedelic effect. The alternation of beams that are solid black with those provided with a playful zigzag line provides an extra playful element with great liveliness. Completely unexpected, the decoration at the bottom of the pipe changes into the usual line drawings in which we recognize a row of tipis, Indian tents and animal figures related to the usual hunting scenes. It is remarkable here that it is not igloos that are depicted, but Indian wigwams. An unanswered question is whether these figures were started and then changed into a geometric pattern or vice versa so that they were added last.

Professionals speak of a so-called West Inuit pipe from Alaska. This makes them opposed to the East Inuit pipes from Asia. The production of such signature walrus ivory pipes must have been substantial. When hunting walruses, each male provided material for two new pipes, as well as raw material for all kinds of other trinkets that sold equally well. Customers for this were the European whalers and gold miners. Makers of these pipes are the sub-tribe Inupiaq, which developed a lively trade between 1890 and 1900. Finally, it is interesting to note that the Inuit pipes have no relationship with the pipes of the American Indians, peoples with which they did not wish to associate. The walrus pipes have previously been copied from Chinese smoking instruments that the Inuit got to know by crossing the frozen Bering Sea in the winter period to trade there.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 24.263