Highlights of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Hoogtepunten uit het Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Publication Year:

2020

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Officer's pipe in a case

This remarkably large meerschaum pipe bowl has a height of no less than 22 centimeters and is made for a specific target group. It is a typical officer’s pipe, used in the first half of the nineteenth century by the highest army commanders to impress. The tobacco pipe has a nearly cylindrical, somewhat constricted bowl, an almost flat bottom with a short ascending stem that widens towards the cuff. The pipe bowl is undecorated with the exception of a shell motif of seven flat lobes at the bottom. It is a decoration that was applied to many pipes, although it is incised here and not raised in relief. From a stylistic point of view we speak of fluting, but the motif is clearly derived from a shell, here possibly with a wink to the maritime origins of meerschaum. Furthermore, the origin of the stem is marked with a circumferential line that brings liveliness to the pipe shape.

Special and certainly prestigious is the original mounting with a hinged cover made of silver in an alloy that is just below our legal level. This cover is in the shape of a tall naturalistic helmet with an arcuate feather. On both sides of this helmet we see a silver applique with a weapon trophy: in the center an armor, further drums and cannonballs, lances, sabers, bayonets and trumpets protrude from the silhouette. The decoration is fixed with soldered screws and meticulous screw-nuts. The conical silver stem holder on a lenticular plate has a wavy opening and a twig with serrated leaves as a securing eye. The well-decorated silverware forms a beautiful contrast with the mirror-smooth meerschaum, especially now that it has been given a dark shade through frequent use.

The original case with a wooden core, hinged at the bottom was preserved with this pipe. The shell motif of the meerschaum is made visible on the outside of the cassette. The exterior of this case is covered with red morocco leather, inside the pipe is protected by green fabric applied on a cotton wool filling. With the beautiful protective casing, the owner can prevent unauthorized persons from spoiling the meerschaum with greasy fingers. That gave peace of mind at a time when meerschaum was only smoked with silk gloves on

Tradition says that the pipe belonged to a Georgian nobleman named Ivan Ivanovich Spet. His name is engraved in Cyrillic script on the stem plate as "C: PET". He was major general and head of Vyatka musketeer regiment from 1789 to 1795. Later he became a general of the Imperial Russian Army. Spet died in 1834. It cannot be otherwise that this product was made in Russia. The Viennese quality standard is not reflected in Russian pipes. Subtle and refined were exchanged for large and bombastic. This is reflected in the size, the design and especially the finish. The silverware is what we call below legal standards, but the amount of silver is impressive. The meerschaum does not have a really light specific weight, its quality here lies more in the fossil aspect of the stone than its light weight and high porosity. The Russians also got their raw material from Turkey. The local miners knew very well that special pieces that are not suitable for one area are accepted in another. It is possible that the beautiful colour is not only created by frequent smoking, but that there is an artificial way of coloring.

As an officer's pipe this pipe played a special, say social role. The highest command of the army had a great need to impress during meetings. Uniform-dominated men's circles regard their tobacco pipe as a personal status object, an additional attribute to their flashy gala costumes. A show-off function with a high status value that we know from various European countries. In Russia, this manifests itself with large and massive smoking equipment. Even the Tsar participated in this, his pipes also did not show great refinement, but were above all impressive in size. General Spet's pipe was later presented as a gift to an unknown English ambassador. This pipe thus reached England to end up in a private collection. By auction the object transferred to our museum collection.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.825

The horses of the San Marco

This seemingly ordinary undecorated pipe bowl in case has a special history. In terms of shape, this pipe with its reinforced bowl base and round bottom is not special. This so-called bag shape is already in vogue in the eighteenth century and this specimen is a very pure example. In the nineteenth century, tens of thousands of pipes will be made in this bag shape. In addition, the quality of the meerschaum can differ, from the most finest first-rate pieces that are maximally light weight to the less popular heavier blocks. For this pipe the best raw material is used which is not surprising. The pipe bowl was intended to be provided with a really luxurious mounting.

At special request of no one less than Emperor Napoleon himself a luxuriously mounted pipe was ordered in 1807 at the skilled goldsmith D. L'Honorey, working at the Quai des Orfèvres in Paris. It was to be a gift from the emperor to his marshal who had made a special act of war shortly before. He conquered the city state of Venice and presented to his emperor as a trophy the famous horses of the San Marco. The four more than life-sized bronze horses had decorated the most important church of Venice since time immemorial and now arrived in Paris.

Very appropriately, the appearance of the imperial gift had to refer to the martial act. L'Honorey did this by designing a lid in the form of a military helmet with visor and placing the four horses of the San Marco as the crest on top of this helmet. The silversmith was not only exceptionally inventive in the artistic part of the design, but also in the technical execution. The lid was high and heavy and should easily be opened to give access to the pipe bowl. At the same time, it had to stay steady while smoking. To achieve this, L'Honorey used a double hinge with an ingenious closing mechanism. By pressing the visor, it slides up and unlocks the lid, which then opens completely with three clicks. The helmet folds back further each step until the pipe bowl is completely free. To make the appearance even more luxurious, parts of the silverware were gilded. Finally, a case maker made a beautiful, fitting casing, internally lined with satin and velvet, on the outside with red leather. The edges were neatly trimmed with gold leaf motives and three hooks made sure that the case was properly lockable.

Given the traces of use on the inside of the pipe bowl, the Marshal has not been an avid smoker. The pipe has only been used a few times and was then carefully stored in the casing for generations. Who afterwards have been the owners of this imperial gift remains unclear. The object surfaced in the Parisian antique trade in 1982 and was bought by one of the most renown Jewish antique dealers in Amsterdam. Twenty years later this special object was handed over to the Amsterdam Pipe Museum.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.425

Pipe with two river gods

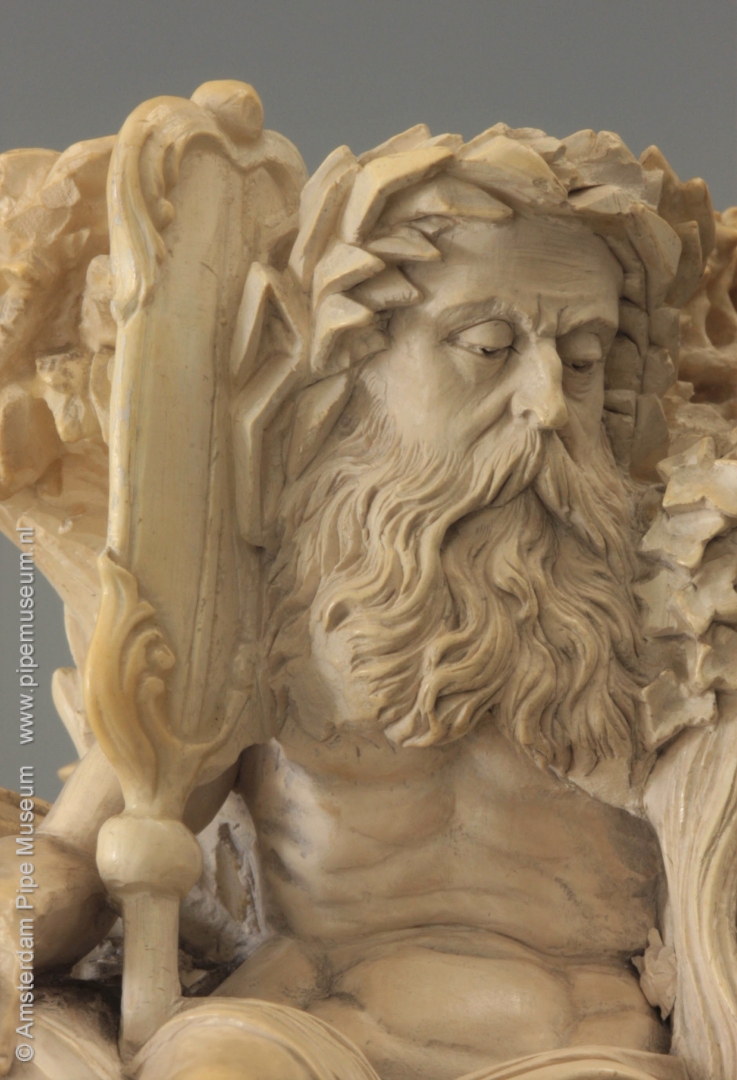

In artistic terms this is the most beautiful pipe in the Amsterdam Pipe Museum collection. It is commonly referred to as the Tweestromenpijp (two rivers pipe). According to tradition, father Rhine and Lorelei were depicted with the arms of a double-headed eagle. The pipe would be a gift from the Habsburg House to a member of the Russian family of czars, although for the rest details remain vague.

Both sculpted persons are shown as stream gods. The Neptune figure fully meets the iconographic pattern. He is depicted as an old man with moustache and long beard, with a wreath of pointed reed leaves around his head. As usual, Neptune is naked with a rag over his loins, as an attribute he holds an oar that brings a vertical accent into the design. His right arm leans on a wide urn from which river water flows. The woman on the right carries vine-like leaves around her head, with the left hand she leans on a pouring pitcher, which gives her as well the title of goddess of the river. At the base is a standing coat of arms with double headed eagle above which the famous Hungarian imperial crown. Around the pipe bowl the scene continues with reeds in which reed plumes on the right and shrubbery on the left. The sketch has been worked out completely which makes you almost forget that a pipe bowl is hidden in the centre.

At the rear, the pipe stem emerges from the scene, which is smooth and thickens to a cuff towards the end. This cuff is decorated with a wide band with stylized leaf motifs and c-volutes. The cuff is mounted with a silver plate with punched motifs soldered along the folded edge. A conical stem holder is placed centrally on this plate. The silver shows traces of gilding.

When we consider that the basic shape of the pipe bowl is an Hungarian, a high cylindrical shape with a round bottom and an ascending stem, we see that the decoration on the different sides is unevenly expanding. That unexpected asymmetrical shape of the pipe bowl may be related to the method of the carver. His artistic ability enabled him to adjust the figuration to the block of meerschaum available to him so that he could use the raw material to the maximum. He was therefore not rigid and cut away what was undesirable in the decoration but made optimal use of the material and thus came to an unexpected composition. If one looks through the eyelashes, one can still see the original shape of the meerschaum lump.

There is something strange about the attribution of the pipe that has been handed down to the Rhine and the Lorelei. The old river god can very well represent the Rhine, one of the longest and most famous rivers in Europe. The Lorelei is not a river but a dangerous rocky point in the German Rhine valley, personified by a woman who watches over the passage. Therefore the name does not match the shown persons. Based on the fact that the pipe is an Austrian gift, we should perhaps look for the real meaning more eastward. If we identify the ancient river god as the Danube, the second largest European river, the younger and smaller river goddess can represent the Moldau. The Austrian imperial coat of arms then gets a logical meaning because both rivers lie within the Habsburg Empire.

Because of the high artistic content we tend to attribute this pipe to a Viennese workshop. Determining meerschaum pipes to production site is not easy due to lack of knowledge. Vienna is always seen as the main city for artful meerschaum carving, the role of Budapest is always underexposed. But meerschaum workers were active in other cities as well. Yet that Viennese attribution for this pipe is justified in this case. The exceptional composition and the beautiful effect elevate this object above all common pipes of that moment. That is why this piece deserves to have served as a royal gift. Seen from the Vienna court, this pipe bowl should certainly be made there. Given the subject and its carving, this must have been between 1840 and 1860.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 1.485

Elegant lady with everything

This opulent meerschaum tobacco pipe is really over the top for most smokers. It shows the bust of an elegant young lady in an evening dress with bare shoulders, surrounded by all imaginable attributes a lady of standing could wish for. She wears a so-called fascinator, a small hat with roses and hanging ribbons, on top of her updo hair. In the right hand with a bracelet, she holds a small umbrella unfolded like a fan behind her head. In her left hand she has a bouquet of flowers and also the end of her swirling scarf. On the same wrist, a fabric bag dangles from two ribbons.

The status of this pipe is not only determined by the large size with a height of nineteen centimeters, it is above all the exceptional dynamism that the woman radiates. The lady has turned her head strongly to the left, while the right elbow is sticking out the other way. The opulent finery of attributes ensures that you have a different, always varied image from every angle. The transparent carving created fragile parts everywhere, which miraculously have been preserved without any breakage. They provide a transparent effect which makes the pipe appear almost weightless. For a meerschaum pipe, which should be as light as possible, this is a positive qualification.

As so often with meerschaum pipes, the origin is a difficult issue. Rapaport assumes an origin in England or France, but a comparable piece is also attributed by him to Fischer in Boston. In other words, he leaves it open. In the cassette with drawings by the Parisian pipe designer Jean Perron that has been preserved, we see similar elegant ladies, but they have never been elaborated so extensively as this one. Other enthusiasts suggest G. Roso from Vienna as a maker, but too little information is known about this carver. The only conclusion is that such eye-catching pieces could only origin in the best production centers where the quality was the highest. Vienna and Paris have traditionally shared first place. Nevertheless, given the extravagant characteristics of this pipe, we cannot exclude some makers in the US, such as the aforementioned Fischer, but also Kaldenberg. The American taste has a preference for the sublime, coupled here with an admiration for Parisian fashion.

Meerschaum pipes have been a collector's item for more than a century, for the beautiful ivory-white material or the entertaining designs. Yet no stylistic research has ever been done into renown carvers and their recognizable style. For example, specific characteristics linked to a particular carver could point us the way to the maker. Note, for example, the unexpected elongated ears. These may indicate a personal carving style, possibly related to a beauty ideal from the time. However, comparative material is insufficient and, above all, too few makers have been identified.

The luxury of this pipe is again underlined by the mounting with a gold-plated brass cuff ring with locking eye, engraved with leaf motifs on the visible side. The same luxury applies to the ivory stem kept with the pipe. This one is also extremely luxurious with an openwork twist around the dark smoke channel, that contrasts beautifully, closed off by two twisted knots. Special is the top of a leopard with ruby eyes, on the back a deer head with moonstone eyes. A flexible part has been inserted to the top. Here it is not a fabric zone as normally, but a piece with alternating ivory and buffalo horn rings that camouflage the ugly textiles but secures the flexibility of this part. The stem end is made of buffalo horn with a flattened ivory mouthpiece.

It is clear that this large pipe bowl has been a showpiece. In view of the fact that the pipe has never been smoked, this indicates more of a presentation piece for a shop window or display case at a chic seller than an utensil for smoking in a domestic circle. With all those fragile details around, the pipe is not very manageable and hardly suitable for use. That is why it never came to smoking and probably will never happen now that the object has been given a museum status.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.313

Pipe in a rosewood box

A valuable pipe deserves to be stored safely. This usually happens in a pipe box or pipe rack, which used to be found in almost every household. Some pipes, however, are stored individually, in a box or close-fitting casing. A nice example of this is the rosewood box with rectangular shape that can accommodate a single meerschaum tobacco pipe. Below the flat lid we see five compartments. Left is a spacious and deep compartment for the meerschaum pipe bowl, around there are shallow pockets for the three parts of the ivory stem. At the far right at the front is again a deeper compartment that serves the three-tassel safety cord. The front of the box is provided with a lock with heart-shaped lock plate of mother-of-pearl. As usual, the box is internally lined with red-brown velvet-like fabric so that the parts will not be damaged.

The tobacco pipe that is stored in this box is not of a great peculiarity, but apparently the smoker‘s favourite. It is a relatively common meerschaum pipe bowl of the so-called Hungarian shape. The base of the pipe bowl is round and merges into a rising stem with a cuff. At the base, the pipe bowl is provided with a popular motif: a shell shape in relief. That motif consists of six outlined lobes and that is remarkable in itself. It is common that this decoration shows an odd number of lobes so that the middle one runs over the centre of the pipe bowl. This is an unusual exception from that habit.

The pipe-bowl is according to general use in the nineteenth century equipped with a silver hinged cover. That lid has a lens-shaped top and rests on ten balls that provide an equal air inlet around the bowl. The lid clamps down thanks to a spring in which three tobacco leaves on a ball can be seen. In the bowl ring of the lid we usually find the silver marks, in this case a "13" mark and the makers stamp or year letter "R". The cuff is also reinforced and finished with a ring in silver with a smooth stem holder and locking eye.

Based on the silver marks, it must be a German product. However, what often happened is that parts from different production centres elsewhere were assembled into a complete pipe. The roughly turned pipe bowl for example could have been supplied from Austria or even from Turkey. The accompanying stem can also be made in a different location, because turning ivory is a separate discipline. The same applies to the box, which does look more English than German. The date of this object must lie somewhere between 1840 and 1870. Most certainly, the pipe is cherished in the box because even after a century and a half the tobacco pipe still is in perfect condition.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.514

A presentation piece with bloody battle

Because of its large size this meerschaum pipe fits into to the category of extraordinary tobacco pipes. The bowl of this showpiece has a height of no less than 23 centimetres and shows around a carved scene of a bloody battle in which sixteen fighters attack each other with axes, knives, swords and bows. In the centre of the scene we see an Arab on a rearing horse who is attacked by a soldier who pierces his chest with a dagger. It is a beautiful depiction that undoubtedly reflects on an existing print of high quality.

In addition to the swirling decoration that has been skilfully worked out with all sorts of interesting details, there is the shape of the pipe bowl itself. With its high cylindrical bowl and heavy stem that flows smoothly from the bowl and ends in a cuff, the shape of the pipe is very characteristic of the 1860s and later. Around the pipe bowl the battle scene decoration follows the shape of the pipe in an attractive bas-relief that is sufficiently picturesque to radiate a great naturalism. The base of the bowl is overgrown with a carved winding foliage, continuing on the stem, alternated with small rocaille-like ornaments. Those motives form a welcome onrnament to the long rather boring shape of the bowl base and stem.

Special is the mounting with a beautifully openwork silver hinged cover with facetted edge, nicely engraved. The lid itself has the form of a ten-sided crown consisting of panels with an embossed standing knight. The inside of the crown is cut open and ends in a point shape. The clip spring has an elegant curl. Despite the white colour, the crown is not cast in sterling silver but made of a lower alloy silver. Because most parts of the mounting are gilded, the gold colour obscures the somewhat grey colour of the silver. Two rectangular hallmarks are stamped on the edge of the cover with the letters "JK", a mark that appears more often on pipe mountings. The metal round the cuff is made of the same material and also features facets and engraving.

All characteristics of this pipe indicate German origin. This applies in the first place to the meerschaum, which belongs to the category of mass meerschaum or pseudo-meerschaum. The pipe is not carved from a large stone, but is pressed from a composite of which meerschaum grit is the main raw material. In the period of making, between 1870 and 1885, large blocks of meerschaum were extremely rare. German factories had long experimented with imitation meerschaum with particularly favourable results. The meerschaum powder was mixed with an adhesive and then moulded. Then it could be carved just like real meerschaum. It even had an advantage for the maker: the stone was completely homogeneous which made work a lot easier. Finally, the Germans were also masters in creating the patina of the pipe so that, even unused, it could get the appearance of a long-smoked pipe.

With its solid shape and transparent lid, this showpiece has been a masterpiece in the pipe collection of a German nobleman. For us in the 21st century, however, the question remains unanswered as to how this pipe was valued at the time. Was the owner aware that he did not have a real meerschaum? Certainly he would have known that the desirable patina was not obtained by smoking but was artificially applied. Apparently, it did not bother him in his pomp and pageantry. Whether the pipe really impressed contemporary connoisseurs remains the question. Anyway, with its somewhat pompous appearance, this product fits perfectly into German culture as we know it from the various country houses. Refinement of material and technology is more an Austrian affair than a German custom. We can see that even in the tobacco pipe.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.550