Highlights of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Hoogtepunten uit het Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Publication Year:

2020

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

A dedicated Staffordshire pipe

The term Staffordshire pottery is a collective name for ceramics from the English region of Staffordshire. In six places close to each other, of which Hanley and Stoke are the best known, earthenware has been made in a great variety for centuries. In the narrow sense, the term Staffordshire also stands for folk ceramics that are often formed in figures and provided with coloured glaze. The pipe depicted here meets all aspects of this definition.

The ceramic tradition in Staffordshire developed so well thanks to the fine plastic clay that was locally extracted and which produced a beautiful white baking product. In the course of time, the potters gained ample experience in working with colourful under glaze. In addition, the figuration of the products became a passion in itself. Tobacco pipes are included in the supply between 1790 and 1840. The most famous family that made this ware was Pratt, which is why the Englishman often speaks of Prattware, although the word Staffordshire remains more accurate.

The best known are the pipes in the shape of a curled snake, the pipe bowl appears from the mouth of the animal, the tail is the mouthpiece. They were dotted in under glaze colours with a preference for ochre and blue, the colours green and brown are less common. Many of these snake pipes were made into two halves in a printing mould and then joined together. They are serial items that were in high demand, especially among the rural people, as an entertaining decorative item.

More surprising are the so-called puzzle pipes, whose stems are twisted and woven into imaginative motifs. That puzzle ware is not made by hand as one would expect, but with the aid of an ingenious device with which endlessly long stems can be produced. The art was in coiling in the most intricate forms. Such a coiled pipe is depicted here and when you follow with your eye the path from mouthpiece to the pipe bowl, it will make you dizzy. Besides numerous ellipses your eyes will make all kinds of hairpin bends and zigzag movements.

The object has a clear view side which emphasize the show function of this pipe. Yet it is a fully functioning tobacco pipe and they were also normally smoked. This specimen clearly shows the deposit of countless times of cautious smoking. The stem end is smoothed for the smoker with some red sealing wax. The pipe bowl itself has a so-called curved shape that is characteristic of the English pipes from the first half of the nineteenth century. On the bowl we see on both sides embossed a standing man with three leaves in hand.

The most remarkable is the stem. The main shape is a lying oval of three turns with pieces turned on both sides, the oval is filled with braid, even on the inside. The stem is painted with dots, stripes and zigzag lines. On the upper winding the inscription FRANCES HIGGANS 1820 is placed on demand. It indicates that this item was commissioned and provided with the name of the donor. It might be a special gift for her father, husband or otherwise for a staff member who received the pipe after years of loyal service. As a showpiece, these kind of pipes often have a long life. They were only smoked on special occasions and were given a safe place behind a glass door of the display case. So they survived over time.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 4.560

A pipe in jasperware

In Josiah Wedgwood's famous factory in Barlaston, England, numerous new types of ceramics were developed since the mid-eighteenth century. One of his most famous inventions is the so-called jasper ware. On a body of clear blue stoneware, lace-like decorations printed in special molds are applied in the color white, making them stand out beautifully. Since this stoneware is impenetrable, it was no longer necessary to use a glaze. This resulted in a product with a matt appearance and an outstanding and particularly refined decoration. An article that was soon widely admired. Given the high price of the cobalt that produced the blue color, a cheaper method was found from 1830 onwards. The colored clay was only applied in a thin layer over the white stoneware shard, on which the white reliefs appeared. In England this was called jasper dip, in this case blue-dipped jasper.

The posh nature of the jasperware made that it was used exclusively for luxury items, including tobacco pipes. The best-known type is the pipe depicted here with a baluster-shaped bowl and an acorn-like cap at the bottom. That cap served as a moisture trap to collect the tobacco juice that is released during smoking. This cap is removable to clean the pipe. Such a moisture trap was necessary because the porcelain-like shard of the product does not absorb.

The decoration of such pipes is done in a specific, classicist style, with themes from ancient times or interpretations thereof that were popular at the time. This type of pottery in antique form was very fashionable when Wedgwood invented jasperware around 1770. It is a decorating style that has always remained popular, even into present day. In this case we see two women standing on the front of the bowl who are making an offering at an altar. One woman holds a small laurel wreath, the second woman is pouring something out of a bowl in the burning fire on the altar, in the other hand we see a covered cup. An oval is suggested by an arrangement of ornamental work on both sides of the scene.

The dating of such pipes goes back to the middle of the nineteenth century. This is confirmed by a catalog of the 1851 World Fair in London, which reports the submission of such a pipe. The description mentions a Staite's patent diaphragm tobacco-pipe bowl, manufactured in stone china by Messrs. Wedgwood & Sons. Wonderfully enough, that pipe is not sent by the Wedgwood factory itself, but by a J. Yerbury, merchant in tobacco from London. It is also unclear what is meant by the word diaphragm. Before the word makes its appearance in photography, the diaphragm actually meant the closure of the human torso into two parts: the chest and the abdomen. We see something similar with this pipe. There is a caesura between the pipe bowl and the moisture lock below it, indicated by a white line, where the two separate parts join together. Presumably the word diaphragm in the description refers to it.

Tobacco pipe production has never been of great importance to Wedgwood. Above all, it was more a supplement to the assortment, or a way to complete it. Nevertheless, the pipe will run for a long time, but probably in small numbers. Later products of this type are also known, often of a somewhat smaller size and simply marked with the imprinted Wedgwood mark.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.311

High quality from Ruhla

The shape of this tobacco pipe is special and very time-bound. It has a two-sided flattened bowl with a nice oval shape that refers to the Empire period. On both sides an extraordinarily artistic relief has been applied. On the left we see two standing women in pleated dress, the left woman with a cornucopia with fruits, the right holding a bowl with flame. The ground on which they stand shows a tree stump on the left. The right side of the bowl is similarly decorated, again with two standing women, the left with a flower basket, the right one holds three leaves.

Special about the pipe is the perfection of the oval shape in combination with the extraordinarily artistically modelled figures. It is clear that a professional has made the mould for this pipe and that, in doing so, he took classic examples as a starting point, reshaping them into the fashion of the day. The urge to perfection can also be seen in the details. For example, the bowl shows a mask head with grapes in the hair at the front. A leaf motif is arranged on the stem side. The upright stem is decorated on both sides with a palmette, a motif characteristic of the empire style.

The mounting of this pipe completes the whole. Typical for the time is the fine bronze casting that is fire-gilded. This work is beautiful in detail as well: watch the fluted motif on the lid with the subtle air inlet along the edge. Around the frame you can see a nice edge of wavy lines that contrast perfectly against the shaded surface. The clamping spring which holds the lid on the pipe bowl has a question mark shape that is also worked. The original stem, still preserved, is of a light wood, assembled with buffalo horn and a safety cord with tassel. The length of that separate stem measures over fifty centimeters and that makes the pipe a smoking instrument for peaceful smoke while seated.

It is nice to philosophize about what the maker meant with this pipe. Did he suggest a wooden pipe with the brown colour? The material, the so-called siderolith, a fine cast clay, however, was more often used to imitate meerschaum. In that case it would be a deep-dark-brown smoked meerschaum pipe. Both options do not seem probable. More likely the mat black appearance would suggest a pipe of the coveted basalt ware: the black stoneware pipes made by Wedgwood in England that the Germans were unable to copy. By giving the surface a deep black colour, a similar result was achieved. Unfortunately, because the paint was insufficiently durable, it disappeared partly over the years and the somewhat disconcerting red shard appeared. That wear now underlines the age of almost two centuries but does not detract from the really successful time-bound design.

Literature: Don Duco, Rondom siderolith, tussen fijnaardewerk en protoporselein, (Around siderolith, between fine earthenware and proto porcelain), Amsterdam, 2018.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.475

Hand-shaped dancing bear

In addition to serial pipes, many unique items were created in the nineteenth century. These are pipes designed by an artist or craftsman and made in an edition of one or only a few pieces. This stub stemmed pipe bowl is a good example in this category. The maker used a brown-gray chamotte clay, which gives a special, somewhat rustic appearance to the result due to its grainy structure. As we see, the pipe is not made of ceramic that makes you think of a glaze, nor a pipe made of the fine, white pipe clay. This makes it a difficult article to classify.

Tradition of hand-shaping and semi-hand-shaping emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century. In contrast to the custom of serial moulding, manual shaping of pipes results in a explicitly artisan look as we see in this pipe bowl. Depicted is a walking bear with a basket on its back and a sort of postman hat on its head. The pace with which he walks is amusing and gives the impression of being a well-trained dancing bear who is very happy to show his tricks.

To determine that it is not just a statuette but a utensil, you have to look twice. If we turn the pipe around, we see that it is actually a pipe. The bear's basket is filled with tobacco and a separate pipe stem is put in the bowl underneath. If you smoke the pipe, the viewer sees the amusing bear with a cloud of smoke rising from its basket.

As often with these kinds of unique objects, no maker or even production location is known. Many of these amusing creations were made in the coastal towns of Brittany, but also in other places artists produced original designs. You can assume that they are not unique creations, but that they are objects handcrafted in a small series. The bear's posture and mobility are too good to be a first attempt. Serial production is certainly a necessity in order to operate in a somewhat economically way. Moreover, it is easier to recreate a design once conceived than to come to a variant creation every time.

To imagine a maker we should think more of a sculptor who was used to providing small sculptures than of a pipe maker. The primary purpose was to do justice to the artistic element. Yet the routine design betrays production in small series, with or without minor differences in detail. The fragility of the material means that not many copies have survived. With this specimen, the enduring of time was ensured because the pipe was kept in a museum collection for a century. As a result, this bear has become automatically both antique and rare.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.672

A presentation pipe from Zenith

Shortly after 1900, the Gouda pipe industry experienced major changes. Until the last turn of the century, production was done exclusively with pipe clay, around 1900 a new ceramic method was introduced. Instead of pressing rigid clay into metal moulds, liquid clay was poured into plaster moulds. The porosity appeared to be increased significantly, resulting in a pipe that smoked drier and cooler. Provided with a tight transparent glaze, a pipe with a much more luxurious appearance was created. This is how the Gouda pottery pipe was born, the pipe on which often a picture appeared during smoking, the so-called mystery-pipe. In addition, various alternatives were created, all of which were mounted in a modern way with a metal ferrule and hard rubber mouthpiece.

This newly created product led to great flourishing in the four companies in Gouda that enlarged their business with this new production line. Their profit margins increased enormously and logically they advertised as often as possible to bring the new product to the attention of the smokers. When the First World War erupts in 1914, the supply of foreign pipes is impeded and these Gouda manufacturers experience good times with their new, modern slip cast ceramic pipes. With the profits they can start a production line in other ceramic objects, the birth of the Gouda pottery.

In addition to their regular products, two pipe manufacturers put a shop-window pipe on the market, intended for the tobacco retailer to advertise their normal tobacco pipes. Both pipes are a greatly enlarged version of the standard so-called doetel, the clay pipe made in a metal mould that was the most common at that time. At the Goedewaagen company, this shop-window pipe is an exact enlargement of the usual doetel and shows the factory name on the stem to make the company better known. Because this shop window pipe referred to a press moulded pipe, the pipe was not glazed. With this choice, the factory saved the tour de force to provide such a large object with a nice even glaze. At the same time, this meant a missed opportunity to advertise the lucrative mystery pipes.

At P.J. van der Want Azn., from 1917 better known under the name Zenith, significantly more care was taken in the execution of the display window pipe. With this cast product it is decided not only to advertise their clay pipes, but also seizes the opportunity to bring the innovative mystery pipe to the attention. The manufacturer does this by placing a striking advertising inscription on the pipe bowl. For a clear message, the pipe must be glazed, increasing the reference to the luxury ceramic pipe.

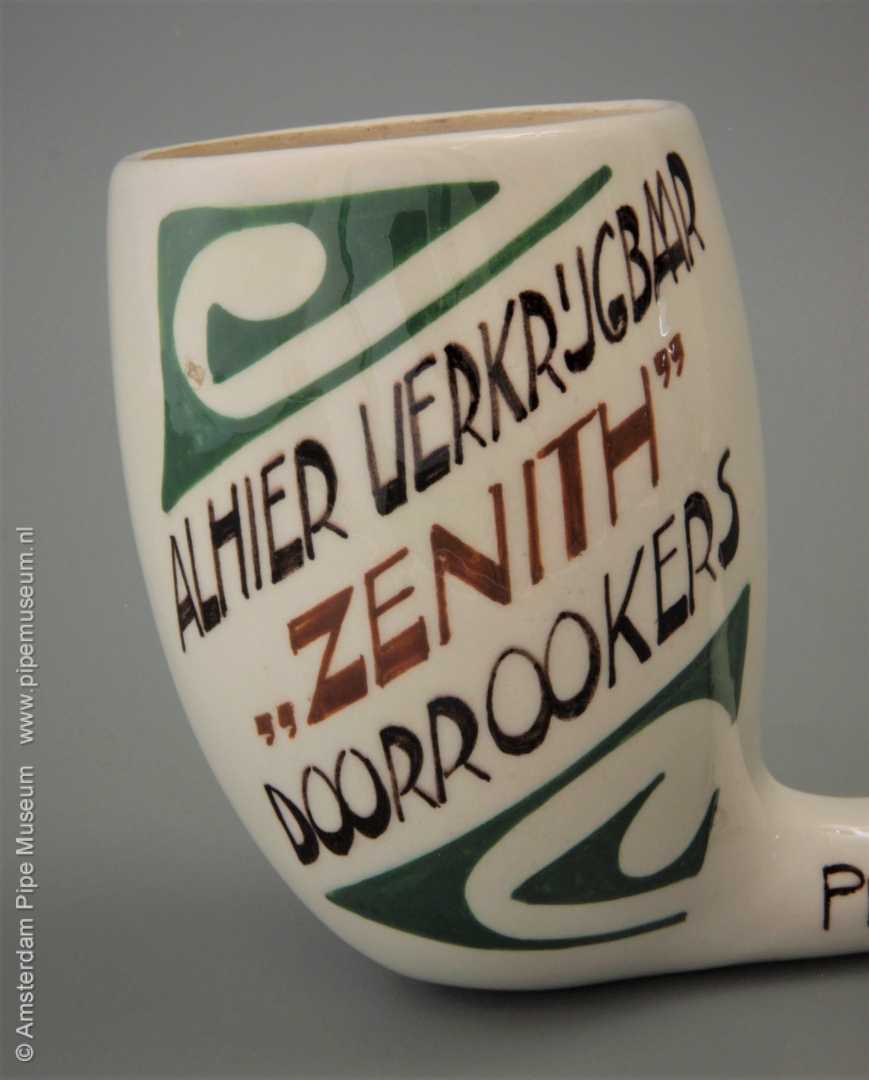

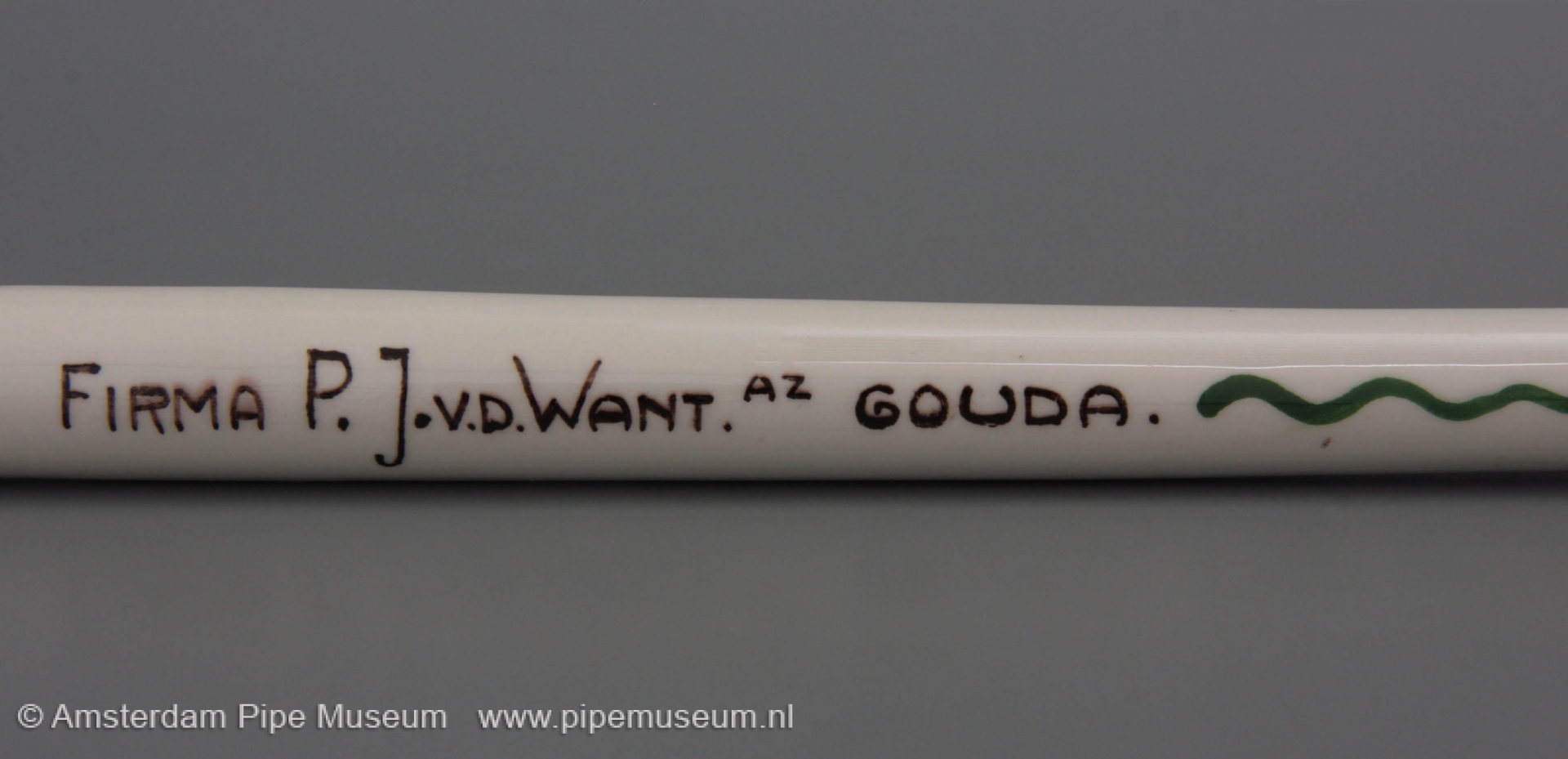

The left side of the display window pipe is chosen as a visible side so this got a lettering on it. Across the bowl we read ALHIER VERKRIJGBAAR "ZENITH" DOORROOKERS (available here "ZENITH" mystery pipes) in beautiful hand-painted letters in two shades of brown. The open space at the top left and bottom right shows a green triangular curl, around 1920 a fashionable ornament that fits well with the Art Deco letters. The factory name is painted on the stem PLATEEL- EN PIJPENFABRIEKEN FIRMA P.J. V.D. WANT AZ. GOUDA ending with a green line and some dots. With its smoothly glazed finish, the Zenith pipe had become a precious object. The risk that the application of enamel on the long stem would fail, was great and the dropout in production would have been considerable.

Evidently such shop-window pipes were made in small quantities. They were only provided to the more important tobacco retailers who could actually advertise them. A small shop in a backstreet was not worthwhile. Nevertheless, the circulation must have been of a certain size. The manufacturer had to made a special mould and that was only profitable with a reasonable production. Numerous examples of the Goedewaagen pipe have been known, but from the glazed Zenith version this is the only known one so far. The dating of this giant pipe is around 1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.953