Tobacco pipes representing proverbs of the Asante

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Spreekwoordelijke Ashantipijpen

Publication Year:

2006

Publisher:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description:

Catalogue of figural tobacco pipes from the Asante in the collection of the Pijpenkabinet with their historical background, including the meaning of the designs in the local language.

The Ashanti and the Fante are the two peoples in South Ghana who belong to the ethnic group Fon and speak the Akan language. The history of the Ashanti began in the tenth century with the migration of this people from the north. Already in the eleventh century a royal dynasty was founded. Under the leadership of the kings, this empire grew into a powerful nation with important trade relations. The kingdom reached its peak in the beginning of the nineteenth century with the kings Guézo and Glélé. Then their territory stretched from the south-western coast of the Gulf of Guinea to the north and north-west of the Niger. The area had fabulous quantities of dust gold. Through the merchant cities this gold was exchanged for other merchandise such as salt. Ghana controlled a large part of the trade route south of the Sahara. After 1850, the Ashanti kingdom has slowly fallen into decline, partly due to the many wars, the slave trade and all sorts of conflicts. Today, the Ashanti region is known as Ghana and there is little left of this once mighty empire.

In art and culture the Ashanti has its own identity. For example, they are known for their potter's art and figurative terra cotta's. The tobacco pipes of the Ashanti have become popular due to the great refinement of material, the special design but also due to the characteristic decorations. I wrote an exploratory article about the normal use pipes [1]. This article is dedicated to one remarkable species, namely the so-called proverbial pipes. It is a luxury version of the daily smoking pipe. Although suitable for normal use, the proverb pipes are still the curiosities under the smoking pipes and they are more of a collector's item or travel souvenir than a commodity. Some of these pipes have even been made as a special commission, which makes that the decoration exceeds the use value. The sculptural aspect of these pipes fits into the culture of which the known gold weights are a similar expression.

This article discusses the phenomenon of figural Ashanti pipes from the collection of the Pijpenkabinet in Amsterdam. The aim is to summarize the knowledge about these special proverbial pipes from the various sources. To start with, I will give a brief history of smoking and the use of the pipe in Ghana. This orientation is followed by the position of the Ashanti pipe in literature and in old collections. The second part will be more product-oriented: the technique of manufacture is discussed, the design principles are explained including the decorations with special attention to the representations in relation to the proverbs and sayings in the Akan language. The appendix quotes the objects from the collection of the Pijpenkabinet in Amsterdam with all available information. For writing this article we have gratefully used two previous studies. The first is that of Rohrer, who described and interpreted the pipes from the Bern museum in a very meritorious way [2]. The second is a work by the Englishman Bullwinkle who studied the Ashanti pipes around 1950 [3]

Tobacco use and smoking

Before more is told about the pipe itself, it is useful first to have knowledge of smoking and the use of tobacco in West-Africa. Tobacco consumption is not much less on the west coast of Africa than in Europe. Evidently the tobacco originally comes from the New World, supplied by European sailors either directly from Brazil or via a European country. The earliest mention of smoking comes from the English captain William Finch, who visited Sierra Leone in 1607 [4]. He discovered there that tobacco was grown at almost every hut and he described the importance of this herb by noting that “tobacco is half of the Negro's food” [5].

It is unknown when the tobacco was introduced in Ghana, although it will not have been much later than in nearby Sierra Leone. In 1705 a certain Bosman writes that tobacco is growing on the coast of Ghana [6]. All natives seem to smoke tobacco, even though the negroes dealing with the Westerners have a clear preference for the tobacco supplied by the Portuguese or even tobacco that comes directly from Brazil. Smoking seems so important that the natives spend their last penny on it. Bosman praises the Negroes who smoke Spanish or Virgin tobacco for their good taste, but ridicules those who are content with Amersfoort tobacco [7]. Apparently the imported local Dutch crop was not very highly regarded at the time and whoever can enjoy the taste of tobacco will be able to confirm this.

From that time pipes are known, described by Bosman, with a stem of reeds or wood of six feet long, on which a pipe bowl made of stone or clay. This pipe bowl is called Taa sen in the Akan language [8]. The stem of the pipe is so long because the pipe is not held in the hand but the pipe bowl is resting on the floor while smoking. In addition to the long-stemmed product, shorter pipes are also known. According to the sources, the natives pack their pipes with three hands of tobacco and smoke them till the end without a break. This must be an exaggeration, since known pipes have a content of one hand of tobacco at the most. Given the amount of tobacco that was put into one pipe, it must be a not too strong mixture.

That smoking is socially established is proven by another note, namely by a certain Mungo Park who writes at the end of the eighteenth century that in almost every city there is a kind of stage where people come together and smoke a pipe. At that time, smoking is seen as a pleasant pastime. Tobacco is called by the Ashanti taa, a word taken from the foreigners, as we see in the words taba and tamaka of neighbouring tribes [9]. The rich language of the Ashanti also has other names for tobacco, some of which indicate a certain type or a particular way of processing [10]. The different words for the tobacco varieties underline its importance within the Ashanti.

Because the Gold tribe was familiar with the American tobacco carots, they prepared their own tobacco in a similar way. After the leaves had dried in the sun, they were rubbed with their hands and the chips were formed into a kind of roll with water. Apart from water, plant juice was also used as a binder [11]. These local tobacco varieties appear to be extremely heavy [12]. Some Ashanti have a clear preference for rather heavy tobacco with a strong stirring effect. This is usually smoked in smaller quantities in a pipe with a corresponding small bowl. For other, milder tobaccos, the Ashanti use pipes with a larger bowl.

We are informed about the rite around the smoking of the Gold tribe by a unique personal account of one Kwame Ketewa from Kwamang [13]. There is no specific moment when a boy smokes his first pipe. As in our European cultures, smoking among boys is often secretive and the heavy tobacco is intoxicating enough to get sick the first time. That happened to Kwame as well. For most pipe smokers, smoking is primarily a group event intended for moments of rest and relaxation. This is also proven with the pipes that cannot be held between the teeth, but must always be supported by hand. The same Kwame also mentions that tobacco is burnt at a funeral, to make the expulsion of the soul easier. When smokers died, it was customary to place their favourite pipe under their pillow, along with some tobacco.

The size of the pipes varies from less than a thimble for the smallest specimens to a content comparable to a normal Western European briar bowl for the standard sizes. Only in case of a prestige object, the bowl content will be even larger, although it is unclear with these products whether they have ever been smoked. While the historic European tobacco pipe is known to have had a clear increase in bowl size over time, this does not seem to be the case with Ashanti. Already in the earliest time both pipes with a large and with a small bowl were used and that remains unchanged until the twentieth century. The different sizes of pipe bowls can be used for the two types of tobacco that were used: the strong Nicotiana rustica next to the milder Nicotiana tabacum.

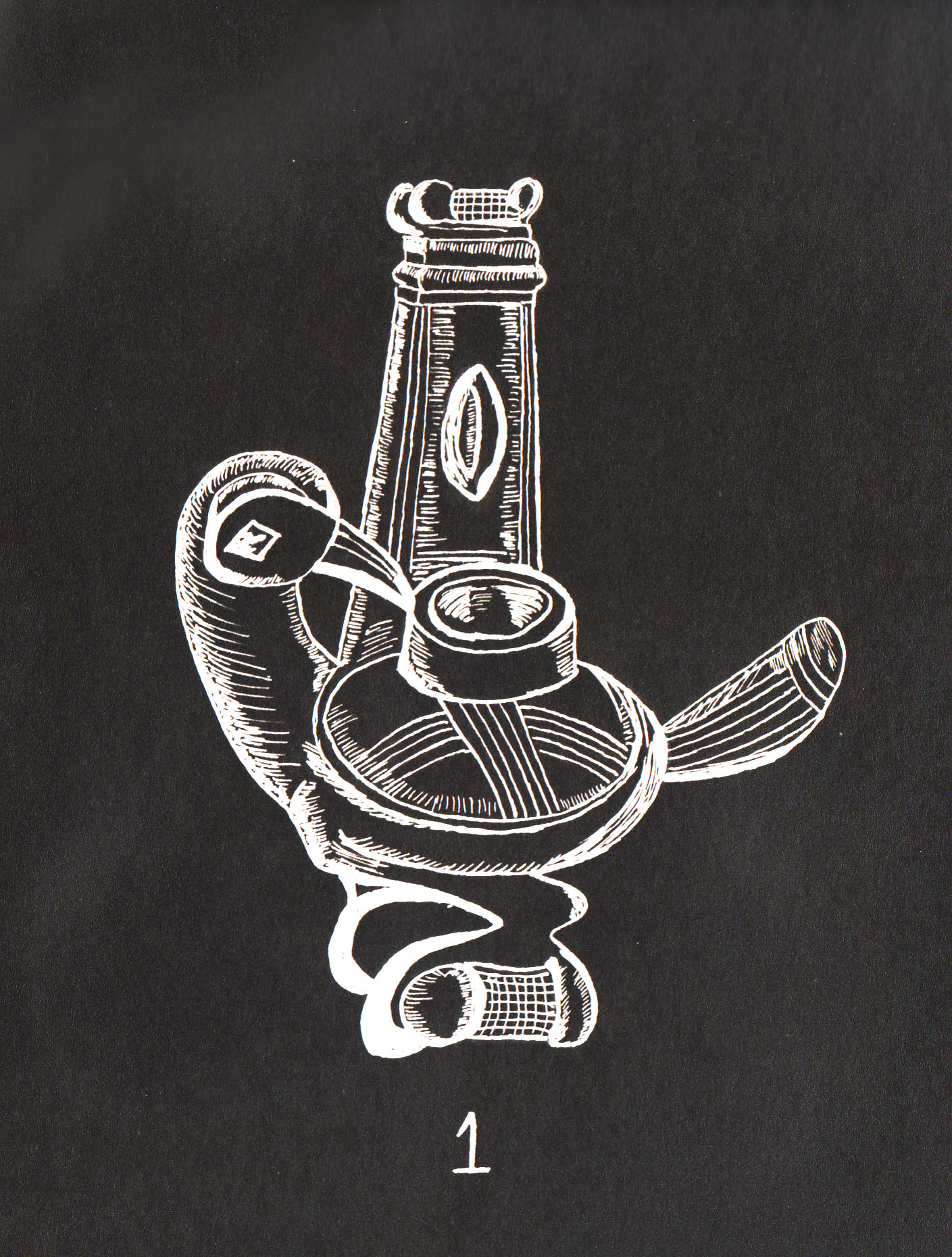

It is clear that the tobacco pipe in the Ashanti culture has played an important role, both for men and for women. Important persons have a servant who assists with smoking [14]. Such a pipe keeper packs the pipe, lights it and monitors the fire, in other words they accompany the entire smoking process. Such an elite smoking situation complete with servant for the pipe is depicted in an Ashanti bronze (Fig. 1). An almost regal person sits on a chair, a guard stands behind him, the long pipe rests with the bowl on the ground, the pipe keeper takes care of it.

More realistic is the photo of an Ashanti equipped with a long tobacco pipe that was depicted on the cover of Bullwinkle's manuscript (Fig. 2). This image shows the then common Ashanti pipe in use demonstrating the status of the long stem. Evidently the pipe is in harmony with the appearance of the smoker. This photo is a wonderful time document of a custom that disappeared in the course of the twentieth century.

Old sources

To get to know the figural Ashanti pipe, studying the sources and making an inventory of pieces in old collections is a worthwhile start. The earliest mention of the figural tobacco pipe of the Akan is an illustration in Bowdich's publication, published in Paris in 1821 [15]. Bowdich deals with Ashanti art and observed a strong influence of Egyptian ideas. The pipes also indicate this technically. Their method of manufacture is very similar to the pipes from the Nile area. Both types were built up in parts and have somewhat similar decorations. Unique for the Ashanti, however, is the sculpting of the tobacco pipes, which is not known from Egypt.

Then it takes until the 1870s before another Ashanti pipe appears in literature. Standard works on tobacco and smoking such as Fairholt from 1859 do not depict ethnographic pipes [16]. When smoking and the tobacco pipe are treated, it is always from the point of view of Europe, possibly supplemented by the prehistory of smoking with the American Indians. Oddly enough, there is no interest in tobacco use in Africa and Asia during that period.

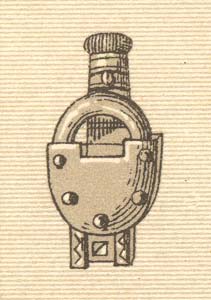

It was not until 1877 that the magnificent encyclopaedia of fashion by Racinet depicted the shape variation of the world's smoking pipes in six pages. A unique series with very varied smoking pipes in which the Ashanti pipe is included [17]. Two examples are shown, a common shape with a convex bowl as I already described in my aforementioned article (Fig. 3). In this context, a figurative piece is more interesting, of which the pipe bowl is very unusual and has the shape of a padlock (Fig. 4).

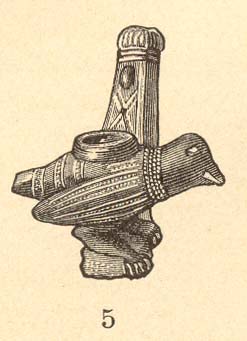

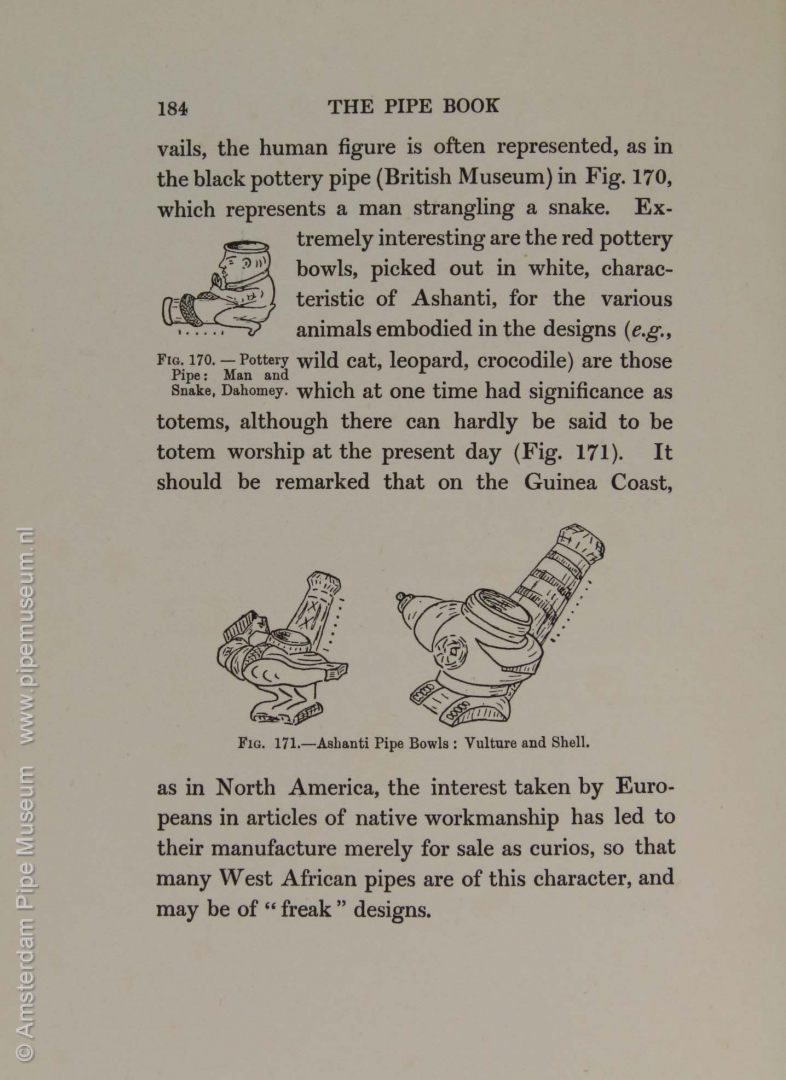

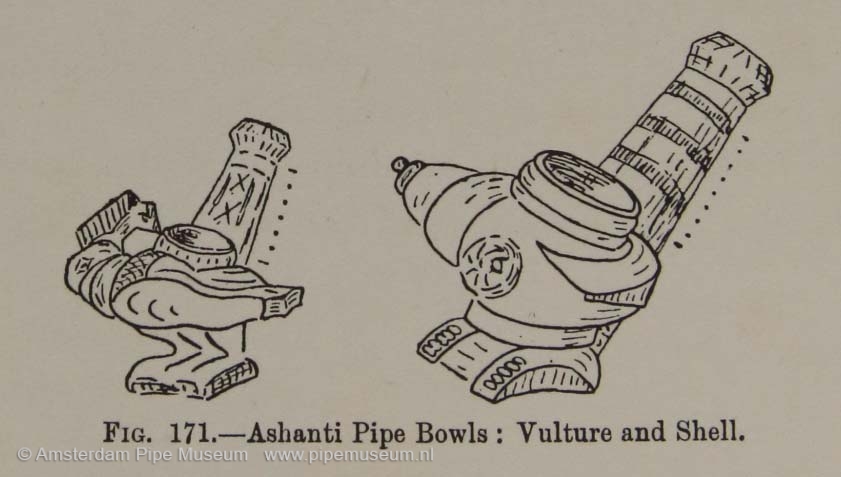

More than ten years later, Robert Pritchett also presents the Ashanti pipe in his beautiful book Smokiana (Fig. 5) [18]. He chooses two pieces from the British museum: a pipe with a pot-shaped bowl and a second with a bird. The publications of Racinet and Pritchett have been of great influence worldwide and ensure that the Ashanti pipe also has a place in other sources about smoking equipment. For example, around 1910 an overview of the world's smoking appliances is included in Dutch and German-language encyclopaedias. The Ashanti pipe is not lacking as a typical example (Fig. 6). From that moment on, the figural Ashanti pipe can no longer be ignored from literature. For example, Alfred Dunhill depicts two such bowls, a bird and a shell, in his 1924 standard work (Fig. 7) [19].

Interesting is what Dunhill says about it: "It should be remarked that on the Guinea Coast, as in North America, the interest taken by Europeans in articles of native workmanship has led to their manufacture merely for sale as curios, so that many West African pipes are of this character, and may be of "freak" designs". Thanks to the worldwide insight Dunhill had built up over the pipe, he was able to compare the pipes of the American Indians and the Ashanti. In both peoples figuration would have arisen from the demand of Europeans for curious objects. Obviously there is no comparison in the designs of the pipes.

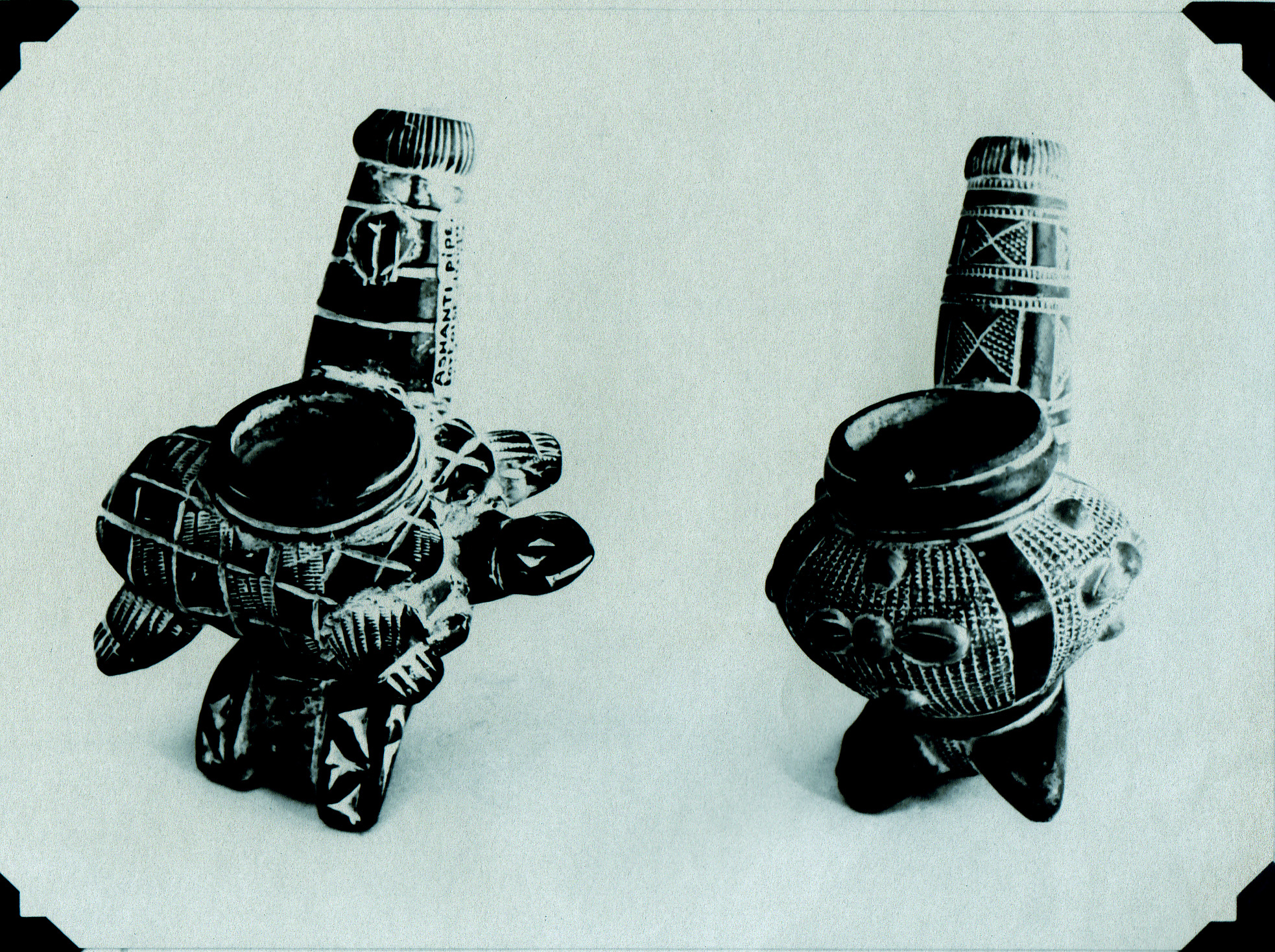

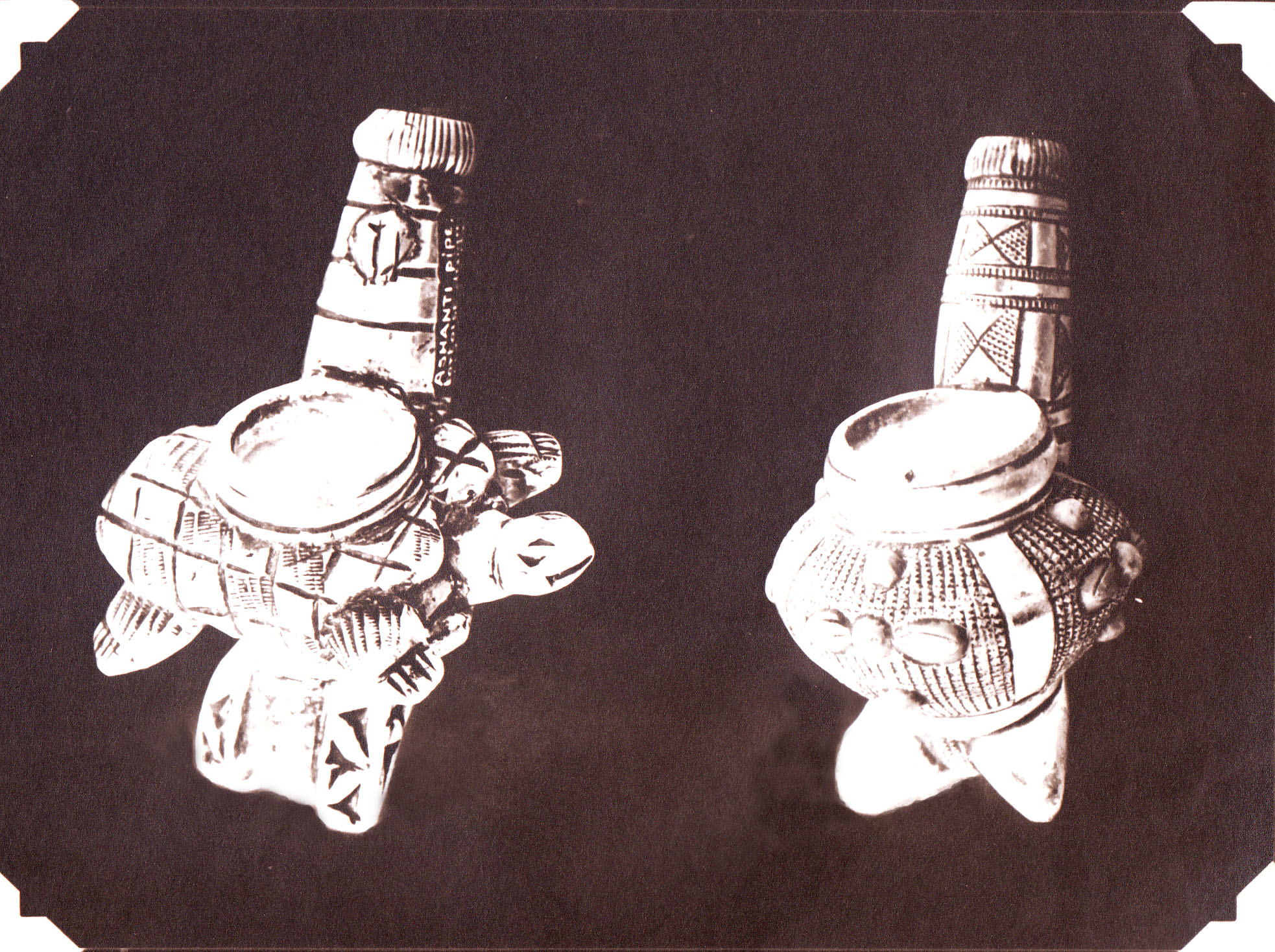

The figural Ashanti pipe did not stay unnoticed by collectors and museums. For example, a full grown showpiece was added to the collection of the British Museum in 1817 [20]. A gift from the already mentioned Bowdich who visited Kumasi in 1817 and bought some pipes that he donated to the museum a few years later. Pictures of two of these products are known. Both copies are richly decorated, one is purely geometric (Fig. 8), the second shows the sitting bird (Fig. 9). These pieces clearly show that the decoration had already reached maturity in the early nineteenth century, both in the geometric and in the figural products.

Another specimen that was created figuratively was in the collection of the Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden (Royal Cabinet of Rarities) of the Dutch King William I. This object was donated by an Ashanti king. Later this pipe was transferred to the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, where it still is on display.

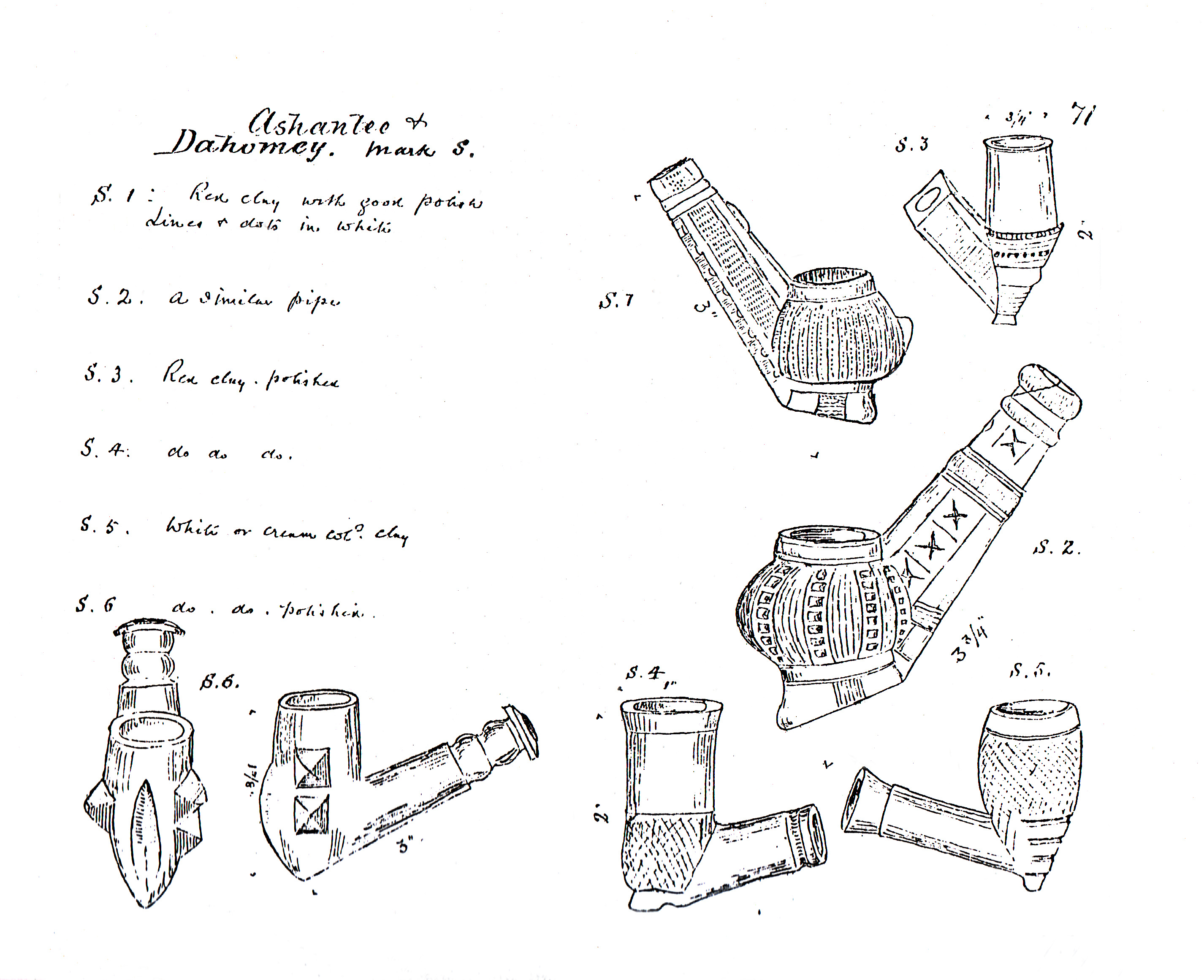

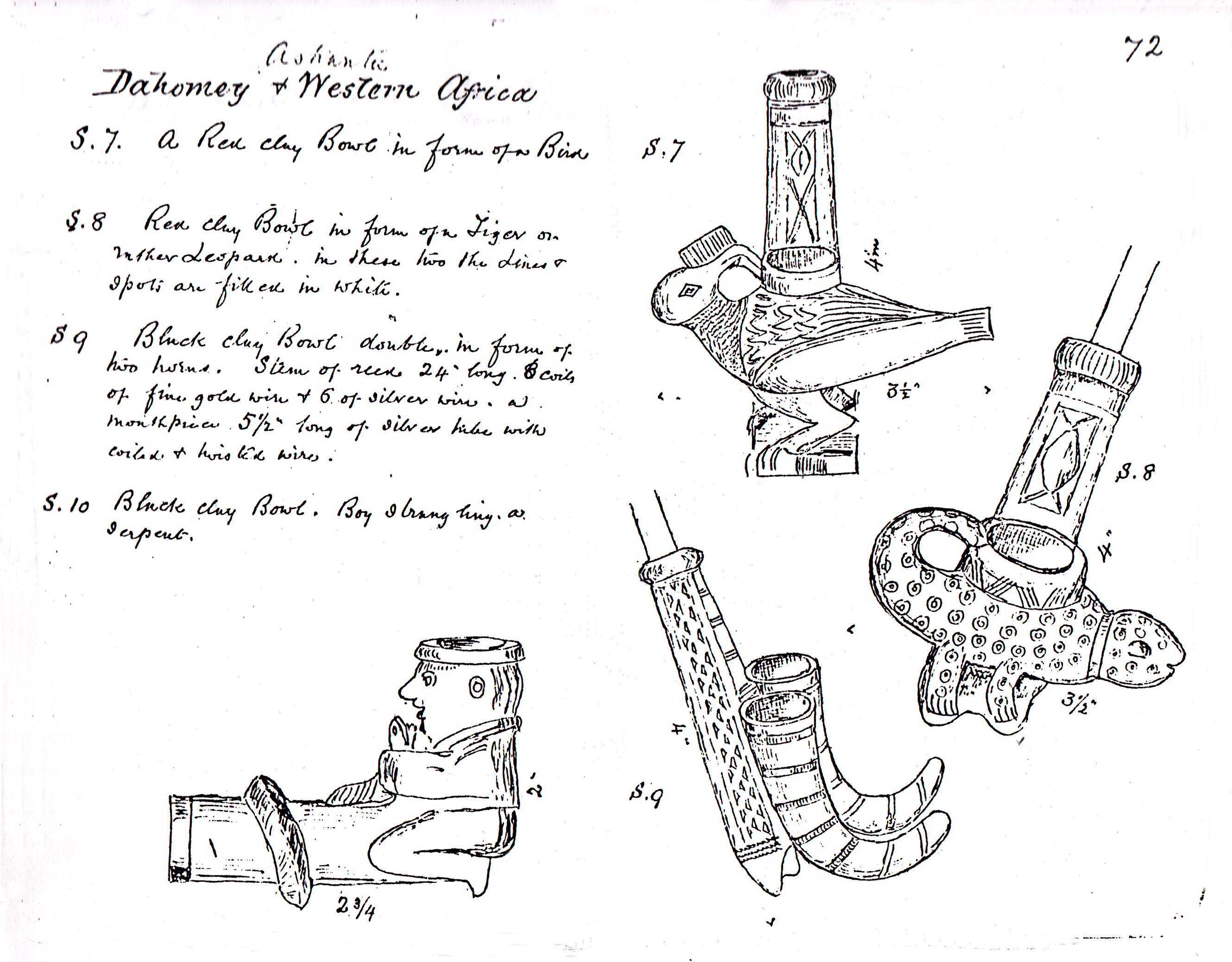

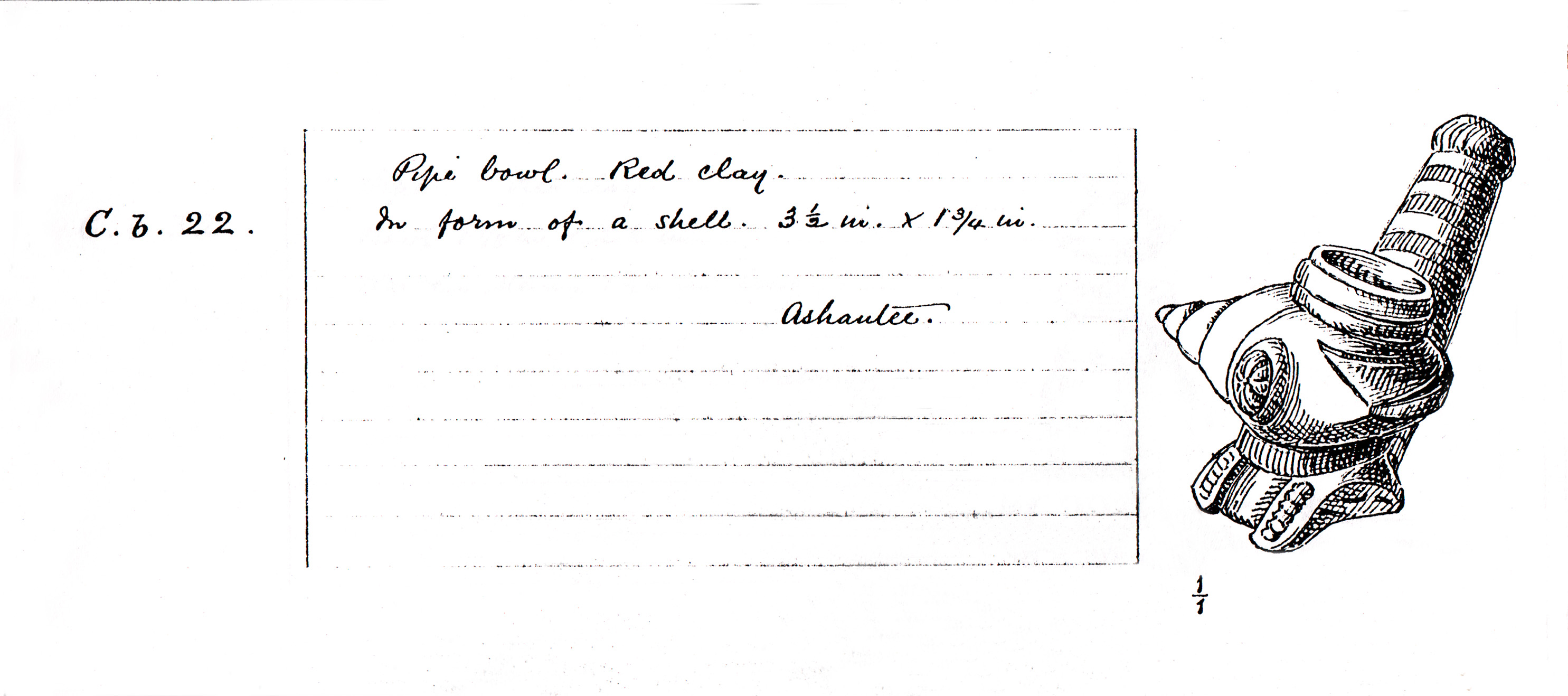

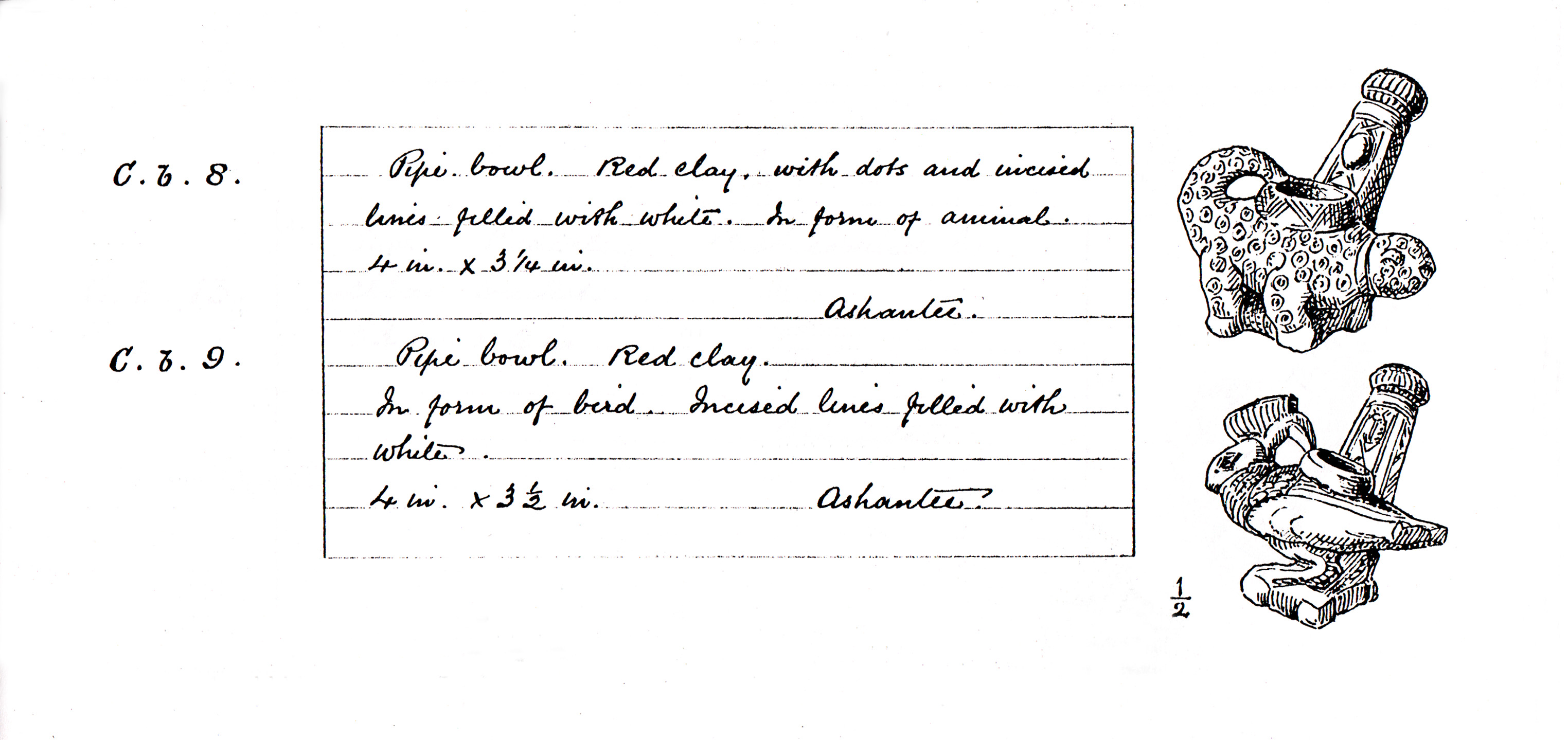

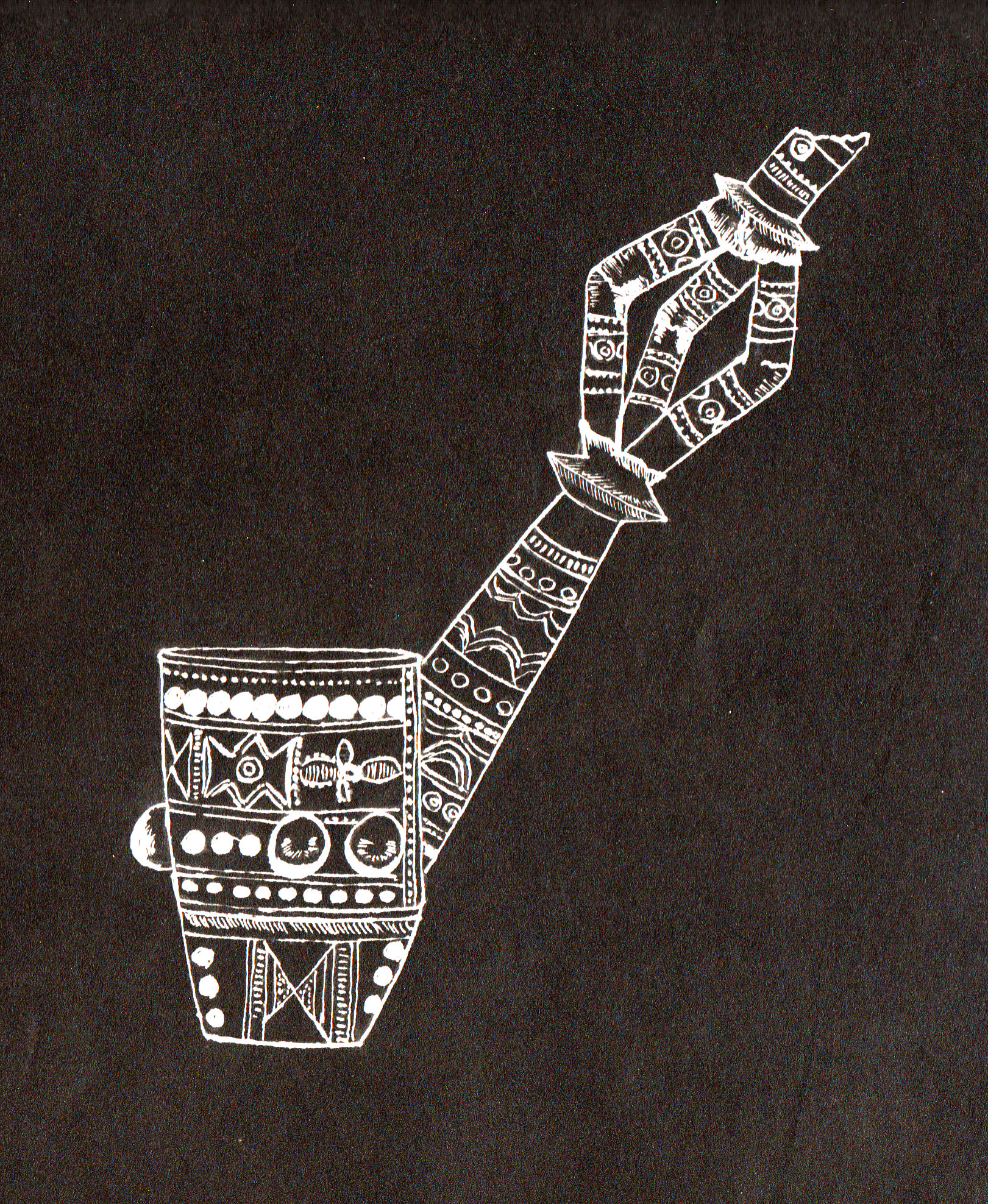

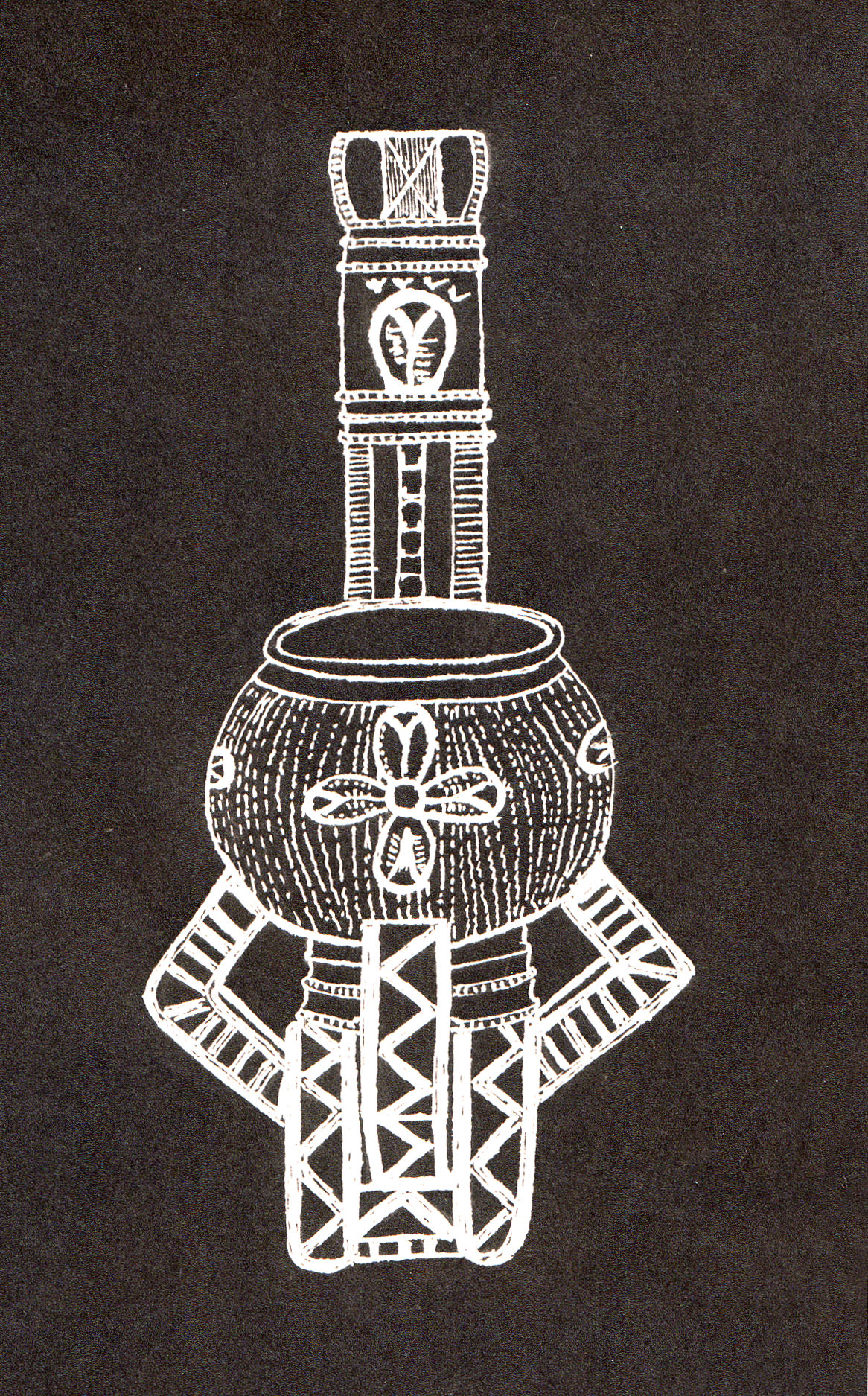

Besides incidental pieces as mentioned above, Ashanti pipes were also to be found in private collections. The famous pipe collector William Bragge from Sheffield illustrates several of these pipes in his notebook, at the time appropriately attributed to the Dahomey-Ashantee (Figs. 10, 11) [21]. We see sketches of a leopard, a bird, a shell and some other representations. Bragge's later handwritten and beautifully drawn catalogue shows more examples (Figs. 12, 13). The group has then grown to a minimum of fifteen. Most of the pipe bowls in his collection are in the shape of the convex cooking pot, the most common everyday pipe.

We owe the missionaries O. Lädrach and J. Jost a special insight into the figural Ashanti pipe. These two people collected not only special sculpted Ashanti pipes in the current Ghana between 1880 and 1910, but also extensively documented these objects [22]. It is a group of about 30 pipes, a collection that has been preserved for over a century at the ethnographic department of the Historical Museum in Bern. In 1946, a certain E. Rohrer published this information collected by them in a meritorious article in which the relationship between the figuration and the proverb or the manner of saying in the Ashanti language is interpreted.

In the first half of the twentieth century, a number of pipe manufacturers and traders in London had a global interest in the appearance of the tobacco pipe. The most famous collectors are Dunhill and Astley. In both collections there were examples of the curious Ashanti craftsmanship. But we also find that interest elsewhere in England, such as in the museum of the tobacco company Will's in Bristol, where half a dozen Ashanti pipes were kept.

A special collection brought together from a completely different point of view was formed by the Englishman Bullwinkle. Between 1920 and 1950 he stayed in Ghana where he collected tobacco pipes. In contrast to the Bernese missionaries, he did not merely look at the figuration in the pipes, but especially at the history of the object and the embedding of the shapes in time. His collection contained about 200 copies of good quality as he himself stated. In addition, he possessed many fragments of bowls and stems picked up from fields. The manuscript he compiled about this collection shows a part of his collection, supplemented with pieces from a few public collections (Fig. 16). Besides Rohrer this is the most important document about the Ashanti pipe. The collection of Bullwinkle and his notes, including the manuscript, are now kept in the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford. A second manuscript of his is in the Pijpenkabinet, ending up in Amsterdam through an auction in London (Fig. 2, 8, 9, 14-16).

Naturally, many Ashanti pipes still are secretly stored in museum depots. This possibility is particularly there if the country has had a relationship with Ghana, which applies mainly to England, France and the Netherlands. Already reported are the collections of the British Museum and the Pitt Rivers Museum. Furthermore, there are some Ashanti pipes in Munich [23]. Unexpected is the presence of a special Ashanti pipe at the Zeeuws Genootschap in Middelburg [24].

In addition to the ceramic pipes, the Ashanti also made tobacco pipes in metal, which predominantly served as status symbol. The famous golden Ashanti pipe of King William I is a good example [25]. This is a gift from a king to a king, offered on the occasion of an agreement about the slave trade. The pipe has a pot-shaped bowl with an upright square stem. A similar pipe of gold is in the collection of the British Museum in London (Fig. 15). Both pipes are not figurative.

A silver pipe of the Bekwai chair was made around 1850 by a goldsmith named Kwabena Fosu (Fig 16). Here the design again shows a cooking pot, which is placed above the fire, the flames of which are beautifully stylized. Finally, as a variant, a bronze specimen is also depicted, the design of which follows the current ceramic pot shape (Fig. 17). The bronze pipe looked like a golden pipe when in fresh condition, but the shine disappeared as a result of oxidation. The pot shape has again been taken as the starting point for this bronze pipe. Of course, metal pipes offer little user comfort.

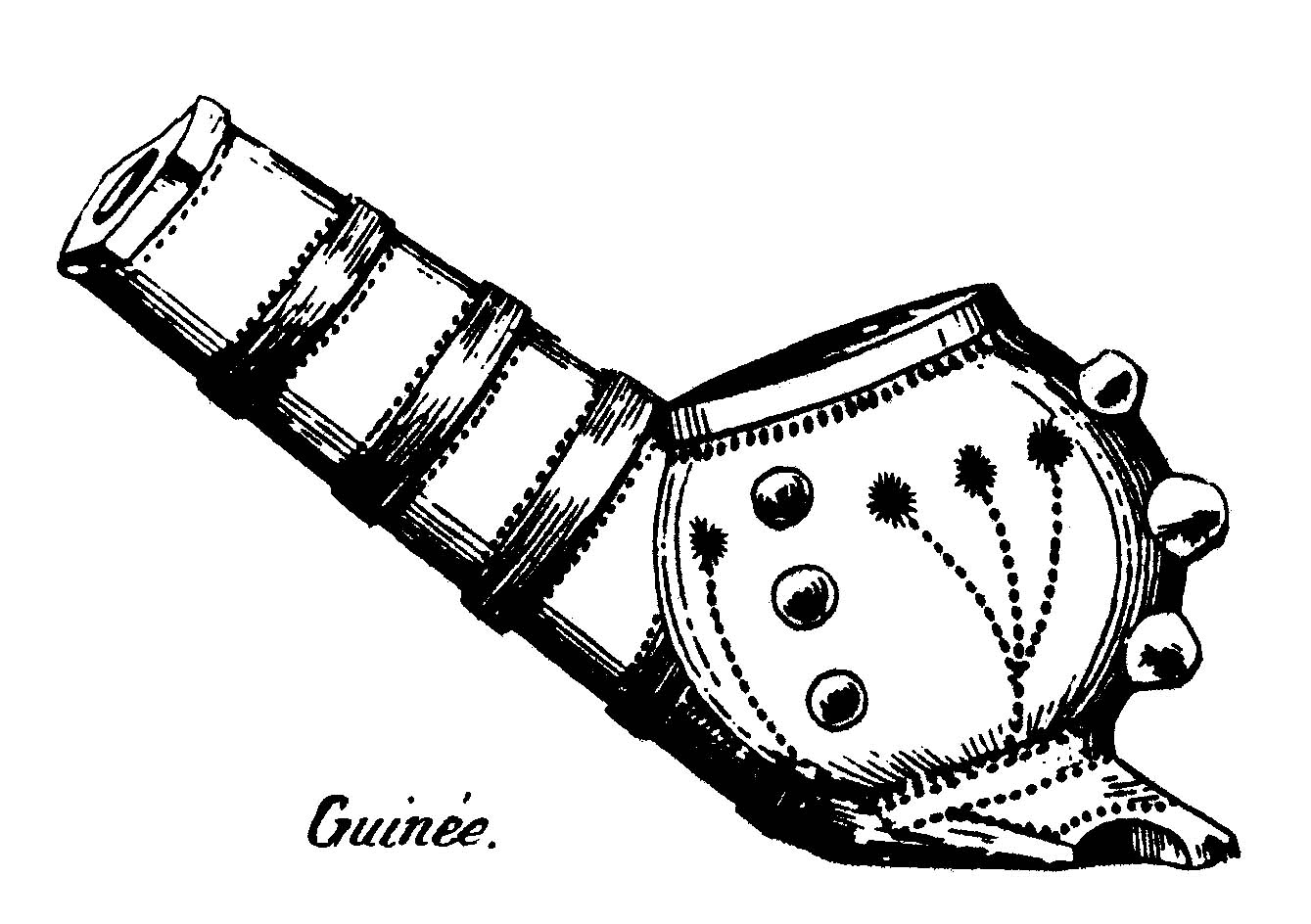

A special pipe in the style of the Ashanti is shown in the catalogue of the French trading house Sailllard from Besançon dating from 1843. On a page with all kinds of exotic tobacco pipes, a spherical Ashanti pipe bowl is depicted with as name Guinée (Fig. 18). It is a wonderful example of a local merit copied by a factory in another part of the world.

The collection of Ashanti pipes from the Pijpenkabinet in Amsterdam is made up of various sources in which a clear two-stream can be recognized. The category of figural pipes is predominantly from old English collections or from the antique trade there. These are objects of liquidated private collections such as Astley's, Dunhill and Shillitoe, but also more public ones like The House of Pipes and the Will's collection. The used pipes in the Pijpenkabinet are without exception originating directly from Ghana. A single figurative piece has a different origin. In the appendix of this article the objects are described in more detail, including their origin .

Technique of manufacture

Feature of the Ashanti pipes is a beautiful fine clay with a regular structure. This clay is extracted in the river beds and then finely ground in a stone mortar with the help of a wooden pestle [26]. This is followed by modelling, in which different techniques are used side by side. At the earliest pipes the bowl appears to have been made on a potters wheel, and then to be stuck to a hand-formed stem. In later times the bowl and the stem are both formed by hand, the stem around a rod to get the smoke tube, the bowl from a solid piece of clay, from which the interior is hollowed out. Then the two parts are stuck together. A third method is modelling completely out of hand, which happened especially with figural pipes. With these specimens, the bowl and stem were hollowed out by hand.

After the basic shape has been achieved, finishing follows. This is done with the aid of small knives that ensure that the surface becomes nicely tight. Finally, the decoration is applied with the help of stamps with which a pattern of lines is zipped or pressed. The geometric motifs contrast with the unprocessed parts and create an attractive interaction. Millings are used to mark out the zones between decorated and undecorated, but lines are also used as marking of fields. We see all sorts of motifs for filling the surfaces, which will be discussed later. In addition to stamping, incisions also take place, whereby repetitive patterns of triangles are cut away and a kind of chip carving work is created. Although geometrically arranged and therefore tight in pattern and rhythm, the motifs are often applied so intensely that we can call these horror vacuï.

The formed and finished pipes are now laid to dry. As a post-treatment they are dipped or topped with potash, a juice obtained from boiled bark [27]. This treatment ensures that the pipes have a uniform colour and gloss after baking, while the surface becomes smoother. Depending on the composition of this engobe, the colour ranges from deep brown-red to orange-brown, while the reflection varies from a soft to a full-gloss surface.

The baking of the pipe bowls is done in a simple field oven. Usually the raw objects are placed between layers of grass and wood, which is then lit. The baking temperature is around 800 degrees [28]. If there is enough oxygen supply during the firing process, the pipes will turn red, caused by the iron oxide in the clay. Another option is reducing firing where the supply of oxygen is barred and the objects are smothered black. This so-called reducing firing achieves a temperature of approximately 600 degrees, which results in the black-baked objects being slightly more fragile [29]. When fired in a correct way when reducing baking, the products get a beautiful metallic shine.

Before the sale, the pipe bowls are rubbed with white chalk or lime [30]. The incised and embossed decorations thus fill to achieve a larger contrast between decorated and undecorated parts. Naturally, this white powder disappears gradually during use. The pipe bowls are supplied by the dealer with a stem, but more often by the smoker himself. These stems are made of reed or wood with a length between thirty and seventy centimetres [31]. At the end, a metal coating is applied as a kind of mouthpiece, for the richest smokers it can be silver or gold [32].

The centre of the pipe production lies in the villages around Kumasi [33]. As it happens, pottery making at the Ashanti is an activity for women, but when it comes to figuration, that is the job of men [34]. This distribution also exists among countless other African peoples [35]. To what extent that tradition has always remained that way is an open question. Our English researcher Bullwinkle mentions in his article some figural pipe bowls made around 1920 by a potter. Obviously, therefore, there was no longer a strict division of labour.

If we compare the normal everyday pipes with the high-ornamented items, or test women's work against those of the men, it is not easy to see any technical difference between the two types. It is clear that the craft was practiced with a strict discipline. The approach is always the same and it is therefore questionable whether the boundary between men's and women's work is so strict. Rather, we find a difference in craftsmanship, in which there are sometimes strong forms and sometimes less pronounced work. The decoration is very convincing in one case, while another product attests to a certain flatness. Great differences can also be seen in the finish: accurate and careful can be found next to hesitating and little routinized.

Model and decoration

In an introductory article I have already discussed the appearance of the common Ashanti pipe. In terms of design, the pipe makers follow a fixed principle that has not or hardly changed in at least two centuries. The oldest bowl shapes seem to have been cup-shaped or slightly conical. Gradually the bucket shape comes into use followed by the pot. The latter is the general bowl shape for the nineteenth century and therefore the most characteristic of the Ashanti pipe. In terms of shape, the pot is more massive and therefore stronger, it replaces the lighter but also more vulnerable bucket shape.

The short stem is conical and is located behind the bowl. The stems of the pipes are also characterized by uniformity, although the handwork produces a large variation in details. The diameter of the stem is round and the stem rejuvenates towards the end. In rare cases, we see stems that are flattened four-sided. The stem ends in an inconspicuous stub, intended to clamp a wooden or cane stem. Usually, the stub is rounded and often adorned with stripes or strokes. The oldest ones have a very modest square stub, although the stem opening is always round. A variant is even pentagonal. It seems that the square stub is copied from pipe bowls from northern regions of Ghana or from Mali.

The bowl is always placed on a base or pedestal. This foot has a flat bottom, which is often slightly inclined to the bowl opening. There is quite a bit of variation in the foot of the pipe, primarily related to the manner of use. The base of the bowl is sometimes flat, in other cases it is slightly bevelled. In general, it is oblique with the lighter products. Such pipes must have been smoked with a short stem and held in the hand. The heavier pipe bowls have a flat base, often with two forward triangular feet. These are pipes to rest on the floor with a long separate stem while smoking. Wear traces on the bottom of the bowl prove this way of use.

In the nineteenth century the flat foot becomes more general and the bowl gets significantly heavier. At the same time, a new, more elegant base is created that is lighter, especially applied to the more luxurious pipe bowls with a greater artistry. Then the base is slightly curved at the bottom and the heavy triangular points are replaced by two forward rectangular feet. At the top these protrusions are often provided with chip carving and sometimes they have an openwork zone.

It is customary to decorate the pipe, usually incised, pressed or stamped or in carving technique. Sometimes we see variations in the form of application of ornaments. There is a large variation in both motifs and arrangement and the manner of execution. Geometric patterns predominate. They are not purely ornamental but have a hidden symbolic function. Geometric decorations are therefore always meaningful, although it is now extremely difficult to understand the underlying message.

The decoration of the stem is usually built up in concentric bands. We distinguish different types. The most explicit pattern shows bands in relief and it appears that these embossments have been made on the potters wheel. These embossed zones alternate with flat bands with stamp or chip carving work. Simpler and more general are the compressed bands or rings, usually repetitively smooth and worked. Sometimes the whole stem is decorated and there is a build-up in beds with an ever-changing filling. In other cases, smooth bands alternate with the decorations. Four-sided stems have a completely different pattern. They do not exhibit a concentric structure, but here the division is usually bound to the four flattened sides, which in turn are divided into beds.

Under the stub on the front of the stem, the pipe maker often placed an accent in relief. Generally, we see a button representing the stylization for the sun or the moon. Another popular motif is also the ntrama or kauri shell, which symbolizes wealth and fertility [36]. In the case of better worked pipes, a representation has been made at this location, such as an animal. Usually the decoration on the stem is subordinate to that on the bowl.

The bowl itself usually has a geometrical background that is roughened with cross lines or a subtle repetitive pattern. Accents are applied to this background, consisting of appliqué motifs. Many geometric decorative motifs are not specific to the tobacco pipes, they are also used on other objects, for example by goldsmiths or weavers. Similar motifs are also applied to the gourds [37]. The geometric decorations usually have an underlying meaning. For example the musuyidie, a square in which a cross symbolizes the removal of evil [38].The cowries, the sign of wealth and fertility, are the most common. They are used in different patterns. Their arrangement in a certain geometric way always contains a deeper message. If they form a star, then it is called nsirewa. The placement of the cowries and their number refer to male or female character. Five is the most sacred, but sometimes their number rises to nine and each arrangement has a specific meaning. In addition, realistic representations occur, such as a snail, bird, snake or other animal. The motives and the manner of execution are always different: sometimes a single figure is shown, then again a choice has been made for multiple representations. The glued details require a lot of attention and often obscure the explicit bowl shape.

A special phenomenon is the figuration of the bowl, to which this article is dedicated. After the pipe bowl was decorated more and more explicitly in the eighteenth century, there was a moment when the decoration became free from the pipe bowl which is the start of the figuration. Apparently, these products quickly gained interest and the pipe maker was encouraged to develop this aspect further. Presumably a stimulating demand from the court was important here. With the Ashanti the king was the example for propagating a material status. He gathered large numbers of objects and decorated his palaces with showpieces of all kinds. That custom was followed in lower circles. In addition, the European demand for curious souvenirs and collectibles will also have a stimulating effect.

It is difficult to determine where the use function of these high-decorated pipe bowls turns into a show function. What is certain is that many of the more elaborate figurations make the pipe bowl too heavy for use as a common everyday utensil. In addition, the fragile protruding details make the pipe unnecessarily vulnerable, whereas when they become damaged or worn, they are rather unsightly than having an added value. That also explains why the more special pipes are usually not or hardly smoked. The English researcher Bullwinkle asserts that the ordinary pipes are intended as smoking pipes, while the figural pieces are pure show pipes ordered by the monarch or by high-ranking persons [39]. Of course, a twilight zone will have existed between the two streams.

The figural representations

As noted, the figurate pipe bowl originates from the ordinary geometrically decorated tobacco pipe. We speak of figural at the moment that the decoration comes loose from the pipe bowl and determines its silhouette . However, with some Ashanti pipes, there is a strong similarity between the bowl shape and the representation. This is the case with the representation of the cooking or family pot, in Akan the abusua kuruwa (Cat.1, 2) [40]. Coincidentally the shape of the pipe bowl is the same as the object that is depicted: a convex pot shape. The same goes for the cup-shaped pipe bowl that is a representation of the o'woaduru, the wooden mortar [41]. With these two examples we cannot speak of figurative, because the representation does not dominate sufficiently and, moreover, does not come loose from the pipe bowl.

Also not figural is the addition to the bowl of a powerful disk shape that displaces the original pot shape of the pipe bowl (Cat. 3) and makes the silhouette of the pipe unexpected. The wide double-cone bowl is inspired by the asenewa a specific water barrel which, in addition to the usual round pot, is the most important piece of household [42]. Like the pot and bucket shape, this representation is not at random, it refers to the proverb: When the pot of the poor breaks, then the gourd is next to it [43]. This symbolizes the fact that the poor are easy to satisfy: if their water pot breaks, they use a gourd instead.

A similar geometric decoration shows a star in the bowl, modelled by having four, five or six points sticking out of the bowl. The illustrated copy shows four points, the fifth is formed by the stem (Cat. 4). With this pipe bowl each star point is decorated with radial rims. There are different meanings for this representation, depending on the number of points and the method of treatment of the surface. Unfortunately, the link with a proverb cannot be made. An interesting variant (Cat. 5) has two bowls, the usual pot shape next to the representation of a star.

Real figuration is had when the bowl is hidden in an explicit representation such as the tobacco pipe where the pipe bowl is dominated by a game board (Cat. 5)). Here the main motif crosses the pipe bowl and the figuration dominates the original bucket shape of the pipe bowl. In the local language the game board is indicated with oware or manga [44], an object with twice seven round dishes along the long sides and one on the each short side. The game board refers to the saying: If you do not have free time, you cannot play [45]. In general, the game board refers to intelligence: the game is played and won by the most intelligent, not everyone can play and win.

We see the same design principles as with the game board with other pipe bowls. A bucket-shaped pipe bowl shows a drum (Cat. 6, 7), again horizontally placed and transversely through the bowl shape. The two examples that are shown are also a nice proof of serial production over a longer period of time. A beautiful tobacco pipe has the same concept and shows a kind of pendant or jewel, consisting of a holder with eye from which two plumes hang (Cat. 8) [46]. Because the decoration requires more attention, the bowl shape does not catch the eye in this pipe. Nevertheless, the presence of the bowl continues to determine the appearance of the object, so that the figural aspect has less impact.

A fourth specimen shows a fruit with the stem to the left (Cat. 9). Illustrated is the green hibiscus, which is eaten a lot in Ghana. Less general is the representation of a fish around the bowl (Cat. 10). Unfortunately, the link with a proverb is not known about this pipe. With these five tobacco pipes, the actual pipe shape is therefore largely unaffected, although it is dominated by an eye-catching decoration that has, as it were, been pushed through the bowl.

Fairly general but still missing in the collection of the Pijpenkabinet is the portrayal of a turtle (Fig. 18) [47]. Here the figuration is usually less strong and there is again a breakthrough of the bowl with a main motif. The turtle refers to the proverb: The turtle says: fast is good, but slow is also good. Other lectures are also known, such as: To catch a turtle one does not have to run and less logical for us: A turtle also has its worries.

A more intense figuration is achieved with the finely shaped shell (Cat. 11), which once again runs straight through the bowl. In this pipe the representation refers again to a way of saying: When the snail hides itself, it becomes big [48], also expressed as: Far from the artillery the warriors are the oldest. A beautiful saying with a very simple explanation: whoever does not enter the danger zone cannot be at risk. It is nice that the Ashanti language is not always unequivocal because there is a second reading for the pipe bowl with shell: If there were only snails and turtles, there would never be the shot of a rifle in the forest [49]. Again the saying is based on the logic of the matter: slow animals do not ask for heavy guns. Possibly the granting of another spell here has to do with a change in the details in the shell or an added stamped or carved ornament. If a different snail house is depicted or if there is an added motive, then the proverb also changes.

From a completely different design is the rather large pipe bowl with the representation of a snake (Cat. 12). The decoration starts in relief on the front of the bowl and the snake body rises with three zigzag windings, the neck and the head of the animal end at the top of the stem. A sitting bird is placed at that location. A second bird is shown on the back of the pipe bowl. The snake normally lives on the ground but in a rare case it grabs a bird from the air. Because of this remarkable catch, the pipe indicates good luck or an exceptional bargain.

The sculptural design reaches full growth with a few pipe bowls in the shape of animal figures. Here the bowl of the pipe is completely subordinated to the representation and usually only the upper edge of the pipe bowl breaks through the figuration. A good example of this is the standing leopard (Cat. 13), where only the bowl opening on the back of the animal points the way to the pipe bowl. The leopard is represented here as a symbol of constancy. The animal refers to the saying: When the leopard's skin gets wet due to rain, its spots are not washed off [50]. The meaning behind this is that animals do not show a change of character in a changed circumstance. Another explanation of the animal does not speak of rain but states that if the leopard falls into the water, his skin will get wet but his spots will not disappear [51]. Rohrer gives an explanation of this last spell that exernal influence cannot overrule the natural gifts of man.

We see the same optimal figurative application in the sitting bird (Cat. 14), where the pipe bowl is hidden in the hull of the animal. In the development of this object, a strong interaction of the surface is mainly obtained by the scarce application of chip carving. In the iconography of the Ashanti four birds occur: the eagle, crow, hawk and cock. In this image, the Ashanti recognizes the eagle that symbolizes the following spell: By going and coming, the bird braces its nest [52]. The meaning is instructive and points out that for all labour time and patience is needed, so that the result is brought about unnoticed.

Two figural pipe bowls stand out due to a very specific design. These are bowls with a standing rooster (Cat. 15) and a standing chameleon (Cat. 16) at the front of the bowl. Both products are unmistakably of the same hand and date from the later times, when the decay of the pipe industry has already started. In both cases, the image is not modelled in the pipe bowl, but stuck to the front. Yet with this remarkable stylization a special artistic result has been obtained. The chameleon is a symbol of unsteadiness and mistrust because it changes colour. However, the proverbs associated with these two representations were not handed down and it is possible that the meaning for the local users in the period of creation had already been lost.

Of very similar design is the pipe bowl representing a monkey, one of the forelegs on the chin (Cat. 17). This pipe was made in the same period as the two animal figures above. Yet the design yields a completely different result: the stylization is less pronounced and the design therefore seems significantly more primitive. The hand to the jaw refers to something wrong that has happened and has to be deeply thought through. The proverb connected to this pipe reads: The chimpanzee says: When you put something in my mouth, I want to get a good word and tell you.

In the portrayal of people, the pipe bowl is usually placed in the head of the sitter, which results in a rather water-headed person. Numerous examples of this type are known and they seem to have been more common as a pipe; they are stronger than other figure pipes and are also found more regular in excavations. Depicted is a simple version with a standing figure, one hand reaches the head (Cat. 18). There are numerous variants on this theme. For example, the collection of the Bern museum shows some interesting variations [53].

With the figural Ashanti pipes it is unclear how much time has elapsed before the imagination has fully developed into an adult figurative design. A view on the origin and development of utensils is a general problem with objects from traditional cultures. Unlike many other African objects, a continuous development can be recognized in figural tobacco pipes. Once the designs have been conceived, we see that the object gradually becomes more conceptual, while in case of imitation the style always changes. Despite the fact that the pottery work of the Ashanti follows a strongly traditional method, a certain style evolution can still be recognized. In addition, the representation is strongly influenced by the artistic ability of the potter: one craftsman is more skilled than the other. The interpretation of these two ever-changing aspects is not always easy.

We see an obvious change in style during the decay of the pottery industry that started around 1900. Simplification and reduction of detail gives a certain degree of flattening in the form and content. At the same time, an attractive stylization sometimes arises with which a new level of merit is achieved. The illustrations of a cockerel depicted in a rather unilateral way (Cat. 15) and chameleon (Cat. 16) are illustrative of this change. These pipe bowls were made between 1900 and 1920. About such black-baked specimens it is said that they were given to the dead as mourning goods. The use utility function would thus be exchanged for a ceremonial one.

The interpretation of proverbs at Ashanti pipes must be done with the utmost restraint. The Rohrer article shows that when decorations differ in detail in the pipe they refer to a different way of saying. This makes it in many cases impossible for us to relate a spell or say to a particular picture. Moreover, the Ashanti language is rich in spells and sayings, thousands of examples are known. A single difference in detail in the decoration often makes the difference. As an example, the cooking pot with added cowries or other representations, where the additional decoration finally determines the proverb.

The representation is not always determined by an existing tradition. In some cases, the customer asks the potter for a certain design and assigns a meaning to it. Then it is not a popular custom with a definite meaning, but a personal message that has no relation with the prevailing tradition. It goes without saying that such personal representations can no longer be interpreted. In addition, it is to be expected that pipes were also modelled for specific customers, which are of a higher quality and also of greater artistry and originality.

Dating

The lack of insight in the dating of the Ashanti pipe has already been discussed. One fact is that the Ashanti had already come into contact with tobacco and pipe smoking at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Tobacco and the habit of smoking must have been rapidly gaining popularity, but when an own pipe industry developed in this area remains unclear. Nor is the appearance of the earliest pipes known. In any case, the shape of the local pipe originated more from its own tradition than from the Europeans who introduced the tobacco. Unfortunately, too few excavations have been carried out in the country itself, which makes it possible to place the products in a certain chronology. What is certain is that the characteristic Ashanti pipe must have been common in the eighteenth century.

The figural pipe appears to have reached maturity in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. The already mentioned objects testify to this in English and Dutch museum collections. However, the development of these mature figural products is not known and, for the time being, it does not seem possible to reconstruct. So the question remains whether figuration has been a sudden emerging fashion or an evolution over a century or more.

The disappearance of the characteristic Ashanti pipe as a utensil comes in the last part of the nineteenth century. From 1880, culture and prosperity quickly deteriorated, the country comes under other influences of government and with that the traditions disappear. The beautifully finished pipes do not hold against imported products from England and the Netherlands. Soon these become subject to imitation themselves, which results in an impoverishment of this craft [54]. However, some traditional pipe makers remain, who continue in their distinctive style for some time.

Around 1920 the Ashanti made the very last pipes in the style of the early nineteenth century. This work clearly shows that the decay was going on for some time. Yet the design is still powerful thanks to the special styling while the use of materials is still excellent. The London collector Shillitoe owned five of these later pipe bowls that must have been presented to him by his fellow collector Bullwinkle. According to Bullwinkle's notes, these were made around 1920 by a woman in the village of Abuakwa at the request of ex-Kumawuhene, Kwame Afram. The fact that these figural pieces were made by a potter seems to be in conflict with tradition. That is not the case, however. It is claimed that the black pipe bowls were used as mourning articles and in that case they are made by women, since women take care of the mourning articles. The style must have died out in the 1930s.

In the second half of the twentieth century the figural tobacco pipe comes back as a sort of historicism. The original style of the Ashanti pipe is copied for the upcoming souvenir market. There is a new design of which I depict two types. The first shows great poverty, because a colourless greyish clay has been used that is not very strikingly modelled (Cat. 22, 23). Although the basic features have remained partly, the design and finish are poor. The powerful design principles obtained through the unique combination of modelling and cutting were diluted to form softly sculpted shapes without any character. All that remains with this set is the banal portrayal of a man and a woman added to a shapeless pipe bowl.

In a second type, the design has gained a lot of strength and these pipes also show more technical similarity with the original method and figural merit. Here the pipes are tightly finished after modelling. Nevertheless, compared to the original products, they are too big, too coarse and too clutter of design. With these two pipe bowls it seems that the idea of the proverbs is expressed again, although it is not known what meaning has been expressed. It might that these products are inspired by preserved specimen from the 1930s. However, there was clearly chosen for a larger size, the maker apparently expected a better sale of this larger version.

Meaning in culture

For the Ashanti the tobacco pipe was a personal article with which the smoker could convey his own message. In that light, pipes are created with an embossed decoration that in the course of time showed figural elements. For the smokers, the choice of a tobacco pipe will in most cases have led to the purchase of an ordinary standard pipe. The market supply of figural products must have been limited and their price accordingly high. The high-decorated pipes rather used to serve as a status object, a special gift or souvenir for tourists and travellers. For that reason, relatively many specimens have ended up in European collections in the state of new, so unsmoked. In Ghana, on the other hand, the number of smoked specimens is very limited, which obviously has to do with the fracture sensitivity of the pipes.

It is clear that the figuration of the tobacco pipe at the Ashanti has been an important phenomenon. It is possible to compare this phenomenon with the fashion in figuration that was unleashed by the French pipe factories in the nineteenth century. The fact that France conquered a world market with the figural clay pipe had to do with the greater use value of the French pipe compared to the very fragile and much heavier Ashanti pipe. In addition, the French figural pipe was produced in series with full attention to user comfort. We do not see that at the figural Ashanti pipe. Interesting in that respect are some of the images in the factory catalogue of a French wholesaler from 1843 [55]. In the middle of other exotic pipes, a typical pot-shaped Ashanti pipe from Guinea is depicted. Good evidence that the Ashanti pipe was reknowned and the pipe merchant assumed it to be attractive among European and American smokers.

The belongings of the monarch or senior person sometimes also include gold or silver pipes. These were brought out once or twice a year to show the people that the monarch could smoke. On that occasion the pipe was partially filled and then lit for a short time to be smoked [56]. Some of these chiefs had a so-called taasenfohene who was responsible for carrying the pipe at public places and who also had to prepare it for use.

The importance of the tobacco pipe among the Ashanti as an exponent of its own culture is proven by a rule of life of the Ashanti King Kweku Dua, who stated that in the streets of Kumasi no European pipes should be smoked and one should not walk with a walking stick [57]. Some years later, in 1869 a law even made his compulsary. The rule of life is characteristic of a realm that attaches great importance to tradition and its own identity. The provision is also typical of the time: it is promulgated when the empire decays and threatens to lose its own identity. A few decades later, the foreign influence can no longer be stopped and the Ashanti pipe is exchanged for cheap import products from England and the Netherlands. The local potters are from that moment on to imitate this import goods. Only a single potter continues with the native product in the stylized style mentioned above until the end of 1930. The occasional revival for the souvenir market is a negligible movement that is more likely to damage the importance of traditional industry.

© Don Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Amsterdam – the Netherlands, 2006.

Illustrations

- Statuette in bronze in lost wax technique with a person sitting on a chair smoking from a long stemmed pipe, a second man holding the chair, a kneeled person taking care of his pipe. Ghana, Asante, 1960-1970.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 7.329 - Asante man in traditional clothing sitting in front of his house, a long tobacco pipe in his hands having a characteristic pot shaped bowl. Anonymous photograph, c. 1930

- Pot shaped pipe bowl of the Asante. Detail of an illustration from Auguste Racinet, Le Costume Historique, Paris, 1877 (1888).

- Figural pipe bowl shaped like a lock. Detail of an illustration from Auguste Racinet, Le Costume Historique, Paris, 1877 (1888).

- Two Asante pipes from the publication Smokiana by Robert Pritchett, the bowl on the right the characteristic pot shape, the left a figural bird. London, 1890.

- The Asante pipe from an encyclopaedia illustrating particular pipes from all parts of the world, the Netherlands and Germany, c. 1911.

- Two Asante pipes from The Pipe Book by Alfred Dunhill, 1924.

- The geometrical Asante pipe from the collection of the British Museum, London, 1817.

- Drawing of a figural bird pipe from the collection of the British Museum, London, 1817.

- Page from the note book of William Bragge, Sheffield, c. 1870.

- Page from the note book of William Bragge, Sheffield, c. 1870.

- Drawing of an Asante pipe with shell from the illustrated catalogue of William Bragge, Sheffield, 1875-1880.

- Drawing of two figural Asante pipes from the illustrated catalogue of William Bragge, Sheffield, 1875-1880.

- Two Asante pipes from the collection of the English collector and researcher Bullwinkle, photograph pre 1949.

- Drawing of the golden Asante pipe from the British Museum, London.

- Drawing of the silver Asante pipe made by the goldsmith Kwabena Fosu.

- Bronze Asante pipe with pot shaped bowl. Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.550.

- Asante pipe from French origin from the catalogue of the trade firm Saillard in Besançon, 1843.

Catalogue

- Cooking pot

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with convex bowl on raised and weighted base with two triangular feet on the front and a flat bottom, ascending upright stem with modest stub. Bowl vertical tracks alternating with very fine and coarse lines, the bowl opening hemisphere with constricted ring. Stem three twisted smooth embossed bands between which two bands with four squares each with crosses. Stub with longitudinal strokes. Thin orange-brown engobe. Decoration originally rubbed with chalk.

Date: 1800-1880

Comments: One of the most common subjects executed in a skilful way. The repeating ornamental surface makes this pipe simple and peaceful in contrast to many pipes that are quite overwhelming. Nevertheless this pipe represents excellent craftsmanship and a great skill in shaping ceramic objects.

Meaning decoration: Depicted is a cooking pot or family pot in Akan language Abusua kuruwa.

Literature: Rohrer, cf. 19. Similar shape but because of the decoration of a chicken on the pot this bowl refers to a different proverb.

Acquired: 2000-Fofane, Kumasi

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.000

- Water pot

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with a bucket-shaped bowl with half-shaped protuberance, the base of the bowl with three stepped constrictions, flat slightly hollowed out foot with two forward rectangular feet, ascending stem with stub. Bowl a high-profile, high-profile disk with four studs on the top and bottom. Foot top simple carving with cross in between field with cross. Steel bands alternately smooth and with ripples, under the stub a smooth stud. Stub longitudinal crossed lines. Decoration rubbed with lime.

Date: 1850-1880

Comments: Strong shape resulting in a contrast between the various parts of the pipe. The difference between the decorated and plain parts is quite strong. The execution by hand is proved by the upper part of the bowl that stands wry on the base. Beautiful engobe.

Meaning decoration: The broad bulbous bowl represents a bi-conical water container called asenewa, which is used next to the ordinary bulbous cooking pot. The proverb that belongs to this says: when the pot of the poor breaks, the calabash lies next to it. The meaning is that the poor are satisfied with few: when their water pot breaks, they simply use a calabash.

Literature: Rohrer, compare 18, 22, 33. The shapes are comparative, but the decoration on the pot with a kauri shell or nods refers to another proverb.

Acquired: 2002-Wills’collection, Bristol

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.708

- Water pot

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with funnel-shape bowl on a weighted base, rising stem with square stub. Bowl the shape of a mortar with base weighting inspired by the water pot with carved geometrical decoration in beds. Bowl opening two rages. Base two forward sticking feet. Stem on a stub accentuation of a round. Black-baked.

Date: 1910-1930

Comments: Despite of the small size a craft full pipe bowl, typical for the nineteenth century tradition.

Literature: Benedict Goes, The Intriguing Design of Tobacco Pipes, Leiden, 1993, p 72. This specimen.

Don Duco, 'The ubiquitos clay pipe', Académie Internationale de la Pipe, Year Book 2001, Paris, 2001, p 61. This specimen.

Acquired: 1990-Francis Shillitoe, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.420

- Star

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with funnel shape bowl, without heel and rising stem with small round stub. Bowl four conical shell motifs decorated with radial rough lines. Bowl opening constricted, triangular flat foot. Stem smooth bands alternated with rages. Red engobe, decoration rubbed with white chalk.

Date: 1870-1910

Comments: Remarkable because of its small size, the details look less refined.

Literature: Benedict Goes, The Intriguing Design of Tobacco Pipes, Leiden, 1993, p 72. This specimen.

Don Duco, 'The ubiquitos clay pipe', Académie Internationale de la Pipe, Year Book 2001, Paris, 2001, p 61. This specimen.

Acquired: 1991-Astley's, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 12.660

- Double bowl

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with two bowls on a weighted base with flat bottom and two triangular feet on the front, rising stem with stub. Both bowls are of a double-conical shape, the right-hand carving of standing windows, the left with three knotted cones referring to a star shape, each point decorated with radial lines, a foot between the two paws of rectangles filled with a cross. Stem four concentric embossed bands between which geometric scratching of rectangular fields with cross. Decoration filled in with chalk.

Date: 1840-1890

Comments: The modelling is not very strong, the clumsy shape shows little contrast between the relief and the smooth parts, due to the chalk the surface nevertheless is remarkable.

Acquired: 2002-Astley’s, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.462

- Playing board

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl, placed on a pedestal with two narrow forward sticking feet, short rising stem with inconspicuous button-shaped stub. Bowl the shape of a game board consisting of a transversely placed oval box with ribs on the sides and on both sides ending in a button with a hole on the top, along the edge on the visible side on both sides six holes. Pedestal on the front geometric field with notched triangles between which a rectangular field with rages, the sides decorated, the bottom kinked. Stem alternately roughened and smooth concentric tracks, the stub grooved longitudinally. Decoration rubbed with white chalk.

Date: 1850-1900

Comments: This object is obvious one of a series proved by the speedy way of making not resulting in the ultimate perfection. Being made by hand the item is slightly wray while the surface is not fine and smooth. The way the playing board is incorporated in the pipe is what we would expect. The ceramic is baked by a low temperature and is rather brittle.

Meaning decoration: In the local language the playing board is called oware (oral information) or mangala (Rohrer, p. 18) and shows a long drawn shape with on both sides seven bowls, on both ends one more. The playing board refers to intelligence: the game is played and is won by the most intelligent player, not everyone can win. The expression that refers to the playing board is: If you have no leisure, you can not play either.

Literature: Rohrer, cf.16. ‘Wunni adagyew a, na wontow ware’.

Acquired: 1985-Brian Tipping, antiques trade, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 1.827

- Drum

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with bucket shaped bowl with halfway geometric element, flat foot with two feet, rising stem with stub. Bowl horizontally in high relief an oval-shaped drum with longitudinal lines, the ends hollowed out, placed on a foot with on the top kerfsnee decoration, in between roughened field. Stem concentric bands alternately smooth and roughened, stub longitudinal standing lines. Decoration rubbed with chalk.

Date: 1860-1910

Acquired: 2002-Wills’collection, Bristol

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.707

- Drum

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with funnel-shaped figural bowl, without heel on weighted base and rising stem with stub. Bowl horizontally in high relief an oval-shaped drum with alternately roughened and smooth strips and flattened end pieces in which a hollow, placed on hollowed out flat base with two feet at the front and decorated with carvings. Stem alternately smooth, lightly curved bands and narrow strokes and unobtrusive round stub. Red engobe, decoration filled in with white chalk.

Date: 1850-1900

Comments: A large and convincing pipe bowl with skilled carving, however not very artistic. The surface colour is darker than normally.

Literature: Armero (Antique Pipes, Madrid, 1989, p 40) illustrates a comparative pipe. The Museum Tervuren in Bruxelles possesses a similar object, number 84.22.02 with tordated stem.

Acquired: 1991-Astley’s, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 12.657

- Jewel

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with bucket shaped bowl with geometric element, half hollow base with two feet, rising stem with discreet stub. Bowl horizontally in high relief a pendant with eye with wound sleeve from which two plumes cross, the ends of which cross. Foot front two forward points with carve trim. Stem twisted incised with a bit of rapping above the bowl. Stub longitudinal standing lines. Chapped reddish engobe. Decoration rubbed with lime.

Date: 1850-1900

Comments: A remarkable and firmly carved design with a clear decoration although the details are not so large. The main subject is in perfect unity with the pipe design and is characteristic for the figurative Ashanti pipes. Remarkable is the tordated carving round the stem.

Acquired: 2002-Wills’collection, Bristol

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.706

- Fruit

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl on an elevated base with hollow bottom, rising stem with discreet stub. Bowl lying an elongated oval fruit of the hibiscus with alternately hatched and smooth lines, the stem of the fruit to the right, bottom pointed. Foot front and side simple kerfsnee of triangles. Stem concentric bands alternately smooth and with rages. Stub along with cogs. Brown-red semi-matt engobe.

Date: 1860-1910

Meaning decoration: Depicted is the green hibiscus that is very popular as food.

Acquired: 2002-Astley’s, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.463

- Fish

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with bucket-shaped bowl with figural element, geometric foot with two points and rising stem with stub. Bowl halfway in relief straight through the pipe bowl stabbing a lying fish with high back, the head to the left, the skin structure indicated by crosswise strokes. Foot on the base carved ornament with between the legs a rectangular field with standing incised lines. Stem alternately bands of standing stripes and smooth. Stub simple zigzag line. Decoration rubbed with lime.

Date: 1850-1900

Comments: Made in the characteristic style of the Asante pipes although the modelling of the fish is quite meagre, while the incorporation of the disk shape half way the bowl does not make the design stronger.

Acquired: 2002-Wills’collection, Bristol

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.705

- Shell

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl on a cylindrical base with two protruding rectangular points and an ascending stem with a discreet stub. Bowl a lying cochlea with the point on the right and the opening on the left, the cylindrical trunk with two intersecting rings, one smoothing the other with cogs, foot with a carved edge on the front and the sides, a hatched connection band between the two protruding points. Stem decoration in three concentric bands divided into compartments with geometric filling, under the stub a button. Stub with longitudinal lines.

Date: 1830-1880

Comments: A beautiful and very strong shape in which the shell is naturally placed in a piling up of shapes of the base, the bowl and the stem of the pipe. The base shows a special detail with two circles going together. The surface is covered with a strong engobe in orange red colour.

Meaning decoration: When the snail is hiding, it will grow, also said as Far from the guns the soldiers are the oldest. Explanation: As long as you stay out of the danger there is no risk. Another expression says: Should there exist only snails and tortoise, a rifle would never be heard in the forest.

Literature: Rohrer, compare 11, 12. Nwaw de neho sie a, na wefa no tope of Ka nwaw ne akyekyere nko a, anka otuo retow wuram da.

Acquired: 1991-Astley’s, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 12.254

- Shell

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl, flat bottom and rising stem. On a flat foot is a twisted shell with embossed kauri on the front, the cylindrical bowl (partly missing) with two concentric rings. Stem decorated with incised bands with cross motifs, a cowry at the back in the middle, stem at the stub and a second cowry. Incision decoration filled in with chalk. Black-baked.

Date: 1700-1850

Comments: Remarkable in size, well-shaped shell, although the overall execution is quite crude and not in accordance with the common fine craftsmanship of the Ashanti pipes.

Acquired: 1993, Ger Luttik, Amsterdam

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 622

- Bird

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl, flat bottom and rising stem with small stub. Bowl sitting bird on a flat rectangular base, looking left, the wings slightly spread, the bowl placed in the body, the smooth bowl opening protruding from the back of the bird, foot square with weighted corners, milling in between. Stem concentric bands alternately smooth and hatched. Under the stub a smooth button, small round stub with longitudinal strokes.

Date: 1800-1880

Comments: A beloved motive that is depicted in many different ways, this example is sturdy and craft fully executed with a scarce pattern of geometrical motives indicating the feathers of the bird.

Meaning decoration: In the iconography of the Asante four birds are distinguished: the eagle, crow, hawk and cockerel. This pipe depicts the eagle that refers to the expression: By coming and going the bird builds its nest, in other words for all labour time and patience is needed, finally leading to a result.

Literature: Rohrer, compare 13. Anoma de ake ns aba, na snrene ne berebuw.

Acquired: 1991-Fofane, Kumasi

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 12.398

- Cockerel

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with funnel-shaped bowl with figural element, round base with flat bottom and ascending stem with stub. Bowl front in high relief almost two-dimensional stylized rooster with comb on the head, the body streaked long with smooth lines interspersed with rages. Bowl undecorated. Stem four circumscribing millings, stub closely spaced alongside longitudinal cogs. Black-baked.

Date: 1910-1930

Comments: This product shows a magnificent stylization of the usual nineteenth century style in which the animal figure is strongly two-dimensional, with great persuasiveness. Unusual but characteristic of the pipe maker is the circular pedestal that forms a nice contrast with the flattened animal figure. The reduced fired baking has given the engobe a deep black gloss. The object is convincing in its design, tightness and hue, unfortunately the bowl and stem decoration is quite primitive and this detracts from the result.

Literature: Arnulf Stössel, Afrikanische Keramik, München, 1984, p 214, foto 61. In style a comparative bird but then with its head in its feathers looking back and noticing everything.

Acquired: 1990-Francis Shillitoe, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.423

- Chameleon

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with funnel shaped bowl with figural element, rectangular slightly hollowed out foot and rising stem with stub. Bowl front in high relief an almost two-dimensionally elaborated stylized chameleon, the head to the right, the tail with an arch to the hind leg. Bowl both sides horizontal rims. Stem four millings. Stub smooth.

Date: 1910-1930

Comments: Because of its stylization remarkable level of abstraction was achieved resulting in a less recognizable animal, nevertheless the depiction shows an attractive but primitive charm. Unusual but distinctive for the pipe maker is the circular base that gives a beautiful contrast to the flattened animal. In contrast the treatment of the up going stem is rather meagre, showing rings with hatching though rather sober in execution. The reducing method of firing surface caused a nice silver shine. The object is convincing in its shape, its stylization and colour, partly broken by the primitive stem decoration.

Meaning decoration: The chameleon is the symbol of infirmness and distrust because the animal changes colour.

Acquired: 1990-Francis Shillitoe, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.424

- Snake

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with high bowl on flat foot with two forward points, rising straight stem with stub. Bowl front embossed snake body with three zigzag around the bowl, neck and head end at the top of the stem with a sitting bird. Stem with three-storey layout with geometric-filled beds. Bowl base front between the protruding legs a rectangular roughened field, stem at the back a second seated bird. Stub ribbed along the length.

Date: 1850-1890

Comments: Unusual in its size as well as in its design because of the height which made it possible to zig zag the snake over bowl and stem so that an almost characteristic stylization is achieved. The bird motive on the stem shows the usual abstraction among the Ashanti art.

Meaning decoration: Depicted is a snake that normally lives on the ground and rarely takes a bird from the sky, this remarkable deed refers to lots of luck or an exceptional bargain.

Acquired: 1990-House of Pipes, Bramber

Collection: Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.458

- Leopard

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl, flat rectangular foot and rising stem with stub. Bowl standing leopard on four legs, the tail curled against the bowl opening, the head left and strongly stylized. The animal is covered with pressed circle holes that are derived from a mottled skin. Rectangular base with buttons on the corners, the raised edges with roughened fields. Stem light four-sided with panels on which incised geometric decoration, stub longitudinal standing lines. Decoration with traces of rubbed white chalk.

Date: 1840-1900

Comments: A popular depiction although the pipe is rather clumsy and stilized that caused a loss of reality for the animal. Also the spots on the skin that are of great importance were executed quite careless and without fantasy which made the depiction quite poor. Beautifully done is the head of the animal with its stilized eyes and mouth add much to the artistic quality of the pipe.

Meaning decoration: The leopard refers to the proverb: Kurotwiamansa toe nsuo mu a neho foe na ne ho nsensane woe hoe. The animal (kyeretwie or kurotwiamansa) is depicted as the symbol of strength: when fallen in the water only his skin becomes whet, not his spots. The meaning is that strong animals do not show a change in character when the circumstances change. Also: When the rain falls on the leopard, he gets wet on his skin, but the spots never disappear (Rohrer p 15).

Literature: Rohrer, compare 7. Osu fws ocebo a, ne ho na sfew; na ne nwaran – nwaran de, smopa.

Acquired: 2002-Wills’collection, Bristol

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.709

- Man hand on his chin

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl on flat bottom and ascending tapered stem with button-shaped stub. Bowl sitting figure with the right hand on the chin, a double necklace around the neck, sitting against the stem, the feet on a flat base. Stem banen with hatching (arceringen) between concentric lines. Carved decoration rubbed with white chalk.

Date: 1820-1880

Comments: A characteristic subject, common among Asante pipes. Because of the compact design this pipe is a relative strong item to use, the majority of these designs have been smoked, not this one. The peculiar proportions in the depiction were caused by the need to place the pipe bowl in the head of the person. Bowl interior does not show a smooth connection to the stem.

Meaning decoration: Hand on the cheek refers to something wrong that happened that needs a serious thought.

Acquired: 1994-Mick Clements, antiques trade, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 13.898

- Monkey hand on ist mouth

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl on flat rectangular base with slightly convex base, rising stem with stub. Bowl front sitting monkey, the right hand in front of the mouth, the left hand on the left knee. Bowl on both sides three horizontal notched bands with chip carving decoration. Stem four millings, stub small longitudinal millings. Black-baked.

Date: 1910-1930

Comments: Bowl interior does not show a smooth connection to the stem.

Meaning decoration: Hand on the cheek refers to something wrong that happened and need a deep thought. The monkey says: When you place something in my mouth, I will take a good word from my mouth to tell you.

Literature: Rohrer, compare 1. Kontromfi se; wohys m’afonom a, na meyi asempa maka makyers mo.

Acquired: 1990-Francis Shillitoe, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.422

- Man hands on his head

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with figural bowl on a rectangular, slightly hollow base, rising stem and stub. Bowl front sitting male with shorts, holding a rectangular box with both hands on the head. Bowl on both sides three incised geometric bands with kerfsneewerk. Stem four millings, stub fine crossed (raderingen) cogs. Black-baked.

Date: 1910-1930

Comments: Relatively late production, well-shaped and nicely polished. Bowl interior does not show a smooth connection to the stem. Made by the same hand as number 20.

Meaning decoration: Hands on the head is a sign of mourning for the loss of near relatives.

Acquired: 1990-Francis Shillitoe, London

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.421

- Sitting woman

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with cylindrical bowl with figural front, flat foot leading to the front and rising stem without stub. Bowl front embossed a seated woman, primitive modelled, hands on knees. Bowl either side of three concentric rings between which there are dashes.

Date: 1980-1990

Comments: Made in the style of the Asante pipes, however shaped without any knowledge of the original way of modelling and not showing any type of perfection this pipe is a poor tourist product. Lacks the traditional base, lacks the common connection bowl-stem.

Acquired: 1991-Fofane, Ghana

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 12.411

- Sitting man

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with cylindrical bowl with figural front, flat foot leading to the front and rising stem without stub. Bowl front sitting man, primitive modelled, his right hand on the knee, the left arm raised to the bowl opening. Bowl at the base and around the opening standing lines around the fire opening a concentric ring.

Date: 1980-1990

Comments: See no. 23.

Acquired: 1991-Fofane, Ghana

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 12.412

- Man hand on his belly

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with conical bowl with figural front placed on a flat rectangular base, rising stem with discreet stub. Bowl front sculpted a man sitting on a stool, the left hand on the belly, the right hand on the right temple. Bowl on both sides incised concentric lines, in between a track with zigzag lines. Stem three compartments with geometric bands with zigzag lines. Foot with plinth on which alternately pressed rounds and cowries. Stub longitudinal lines. Red shard, black fired.

Date: 1990-1995

Comments: Starting from the original design of the Asante pipes a fully new concept is achieved with this piece, which is not practical to use because the joint between stem and bowl are not smooth, furthermore the pipe is unpractical because of its weight.

Acquired: 1997-Fofane, Ghana

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.813

- Man with hands folded

Description: Tobacco pipe of earthenware with cylindrical bowl with figural representation placed on a flat base, rising stem with discreet stub. Bowl front sculpted a man sitting on a stool, hands folded together forward. Bowl both sides three double incised concentric rings. Stem three geometric bands of concentric rings between which a dot band. Stub along dotted lines. Red baking.

Date: 1990-1995

Comments: Compare no. 24.

Acquired: 1997-Fofane, Ghana

Collection: Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.814

Literature

Bullwinkle, (Manuscript on Ashantee Pipes), Part I: Tobacco, Part II: Taa Sen – Tobacco Bowls, Part III: Decorative motifs on Pipes of Type I, Part IV: Designs on pipes of Type I, typesript England, c. 1948.

Don Duco, 'Tabakspijpen uit het Ashanti-gebied', Amsterdam, 2001.

Alfred Dunhill, The Pipe Book, London, 1924, pp. 184, fig. 171.

Benedict Goes, The Intriguing Design of Tobacco Pipes, Leiden, 1993, pp. 72-73.

Jean Lecluse, La pipe de l’Afrique du Noir, Liège, 1985.

Rohrer, ‘Tabakpfeifenköpfe und Sprichwörter der Asante’, Jahrbuch des Bernischen Historischen Museums in Bern, Ehnographische Abteilung, XXVI. Jahrgang 1946, pp. 7-24 + 5 Tafeln.

Arnulf Stössel, Afrikanische Keramik, München, 1984, pp.213-215.

Peter Valentin, ‘Les pipes en terre des ashanti’, Arts d’Afrique Noire, 19, Automne 1976, pp. 8-13.

Notes

- Don Duco, 'Tabakspijpen uit het Ashanti-gebied', Amsterdam, 2001.

- E. Rohrer, ‘Tabakpfeifenköpfe und Sprichwörter der Asante’, Jahrbuch des Bernischen Historischen Museums in Bern, Ehnographische Abteilung, XXVI, Jahrgang 1946, pp. 7-24 + 5 Tafeln.

- Bullwinkle, (Manuscript on Ashantee Pipes), Part I: Tobacco, Part II: Taa Sen – Tobacco Bowls, Part III: Decorative motifs on Pipes of Type I, Part IV: Designs on pipes of Type I, typesript England, c. 1948.

- Berthold Laufer, Tobacco and Its Use in Africa, Chicago, 1930, p. 7.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 1.

- W. Bosman, Voyage de Guinée, London, 1705, p. 319.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 1.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 4.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 2.

- Kesi, ahabantaa, asra and ahuahaa. (Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p. 2)

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 2.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 3.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 3.

- Rohrer, 1946, p 9.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 6.

- F.W. Fairholt, Tobacco: its History and Associations: Including an Account of the Plant and its Manufacture, London, 1859.

- Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk18.319c. Auguste Racinet, Le Costume Historique, Paris, 1877 (1888).

- Robert Pritchett, Ye Smokiana, Pipes of all Nations, London, 1890, p 31.

- Alfred Dunhill, The Pipe Book, London 1924, p 184.

- Bullwinkle, c. 1948, p 6.