English influences in an unusual Dutch product of c. 1830

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Engelse invloeden bij een ongewoon Delfts produkt van ca. 1830

Publication Year:

1990

Publisher:

De Tijdstroom

Journal:

Maandblad Antiek

Description:

Article on a ceramic tobacco pipe with a long wrought stem made in Delft by the English potter Piccardt.

The situation in the Delft potters industry around 1800 was far from positive. Over two centuries the workshops had flourished and were able to do good business selling impressive quantities of the renown Delft blue products. This ware is characterized by a red or yellow shard covered with a radiant white tin glaze on which a decoration was painted. For extra shine sometimes transparent lead glaze was added. Technically, traditional Delftware was still a quality product of the first order, but on the other hand the ceramics were fragile and their production rather expensive.

In England, a new type of ceramics was developed in the eighteenth century, which could be produced more cheaply and met new aesthetic and changing usage requirements: it is the so-called "cream-ware". The material was more related to China porcelain and less fragile than Delftware. This type of pottery has a fine, white chalky shard, covered with a tight transparent glaze. The result gives a specific creamy white coloured pottery with a low specific gravity. This was decorated in under glaze and many decorations were not painted but printed, sometimes the colours are still filled in by hand.

By the end of the eighteenth century this English cream-ware was fully exported to the Netherlands. Thanks to the simple production line and serial manner of decorating, it could even be advantageously offered, even including transportation costs. This reduced the interest in the famous Delft earthenware and in that city the number of traditional pottery companies fell back. Shortly after 1800, only seven old-fashioned bakeries worked in Delft. In order to survive they had to switch to the fashionable cream-ware, which in Holland is called "Engels aardewerk” (English pottery).

The factory that drew the lead in the development of English pottery was "De Porceleijne Fles". In 1804, this company passed into the hands of Henricus Arnoldus Piccardt, a lawyer investing in the local industry. The struggle of Piccardt for the survival of this company that flourished for generations is described in detail in a creditable doctoral thesis.[1]

The history of this factory is exemplary for the entire Delft ceramic industry, which had to focus on a product of a different nature. Piccardt was involved in setting up a new production line for which he asked craftsmen from England to bring over their own know-how. These craftsmen worked according to English recipes and often even with British raw materials. So, gradually a product was launched that could be the equivalent to the English. That this change was not an easy one is evident from the series of difficulties encountered. Piccardt, who belonged to the dignitaries of the city of Delft, was forced to submit several requests for subsidization to the city council because of financial difficulties. According to his say to maintain production for the benefit of the Dutch industry.

Unfortunately, limited information has been found about bulk goods made in Holland with cream-ware features. In view of the print decoration and the favourable sales price, it was not immediately considered a luxurious item. It is true that in the civil or rural environment it will have ended up as a decorative item in a wall rack or small display cabinet, but served mainly at the dining table with the daily meal as consumer goods. In wealthy households, the English pottery did not even go further than for use in the kitchen. In many cases, this new type of earthenware will have been the replacement of folk pottery that has been in use for centuries, making the simplest tableware of red earthenware waterproofed by a transparent lead glaze. In comparison, the lighter, finer cream-ware was a big improvement and fitted better in the fashion of the late eighteenth century. However, the vulnerability remained a problem. The shard was not very break-resistant and the glaze did not always reach the right degree of hardness, which caused it to flake quickly. Differences between shard and glaze often gave crazing. In this crackle, too often a discolouration occurred especially by the effect of grease, which soon gave the product an unattractive appearance.

Little is known about the product comparison between English cream ware and that made on Dutch soil. It is clear - and the factory statistics prove this - that "English pottery" was produced in both countries and that the Dutch market was served by both domestic companies and English export shipments. From price lists and entries for Piccardt's exhibitions, we can conclude that the production of De Porceleijne Fles consisted for a large part of English earthenware. The archives contain tea mugs, tea sets, plates and so on. Unfortunately, there is only a limited amount of other ceramic objects.

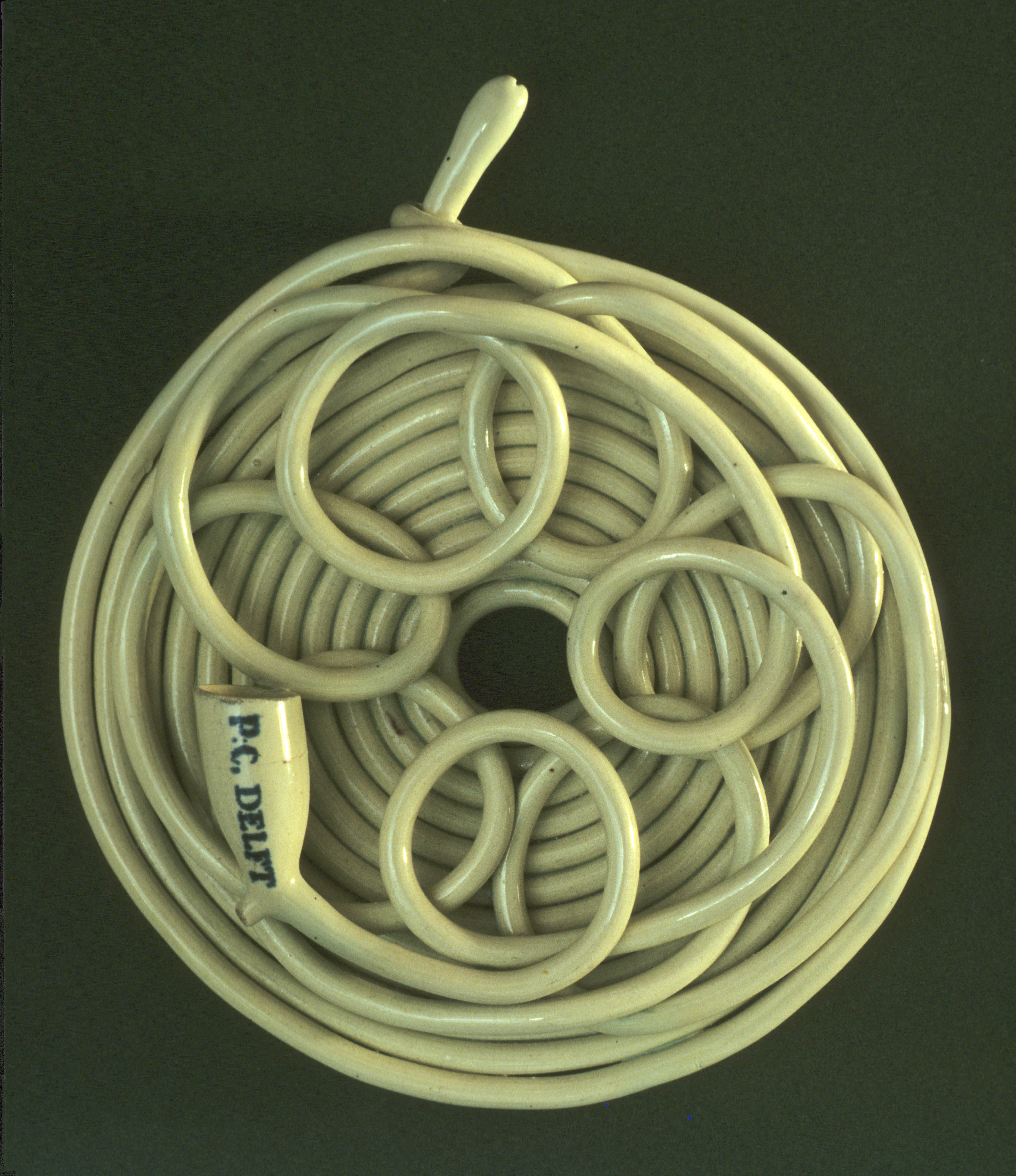

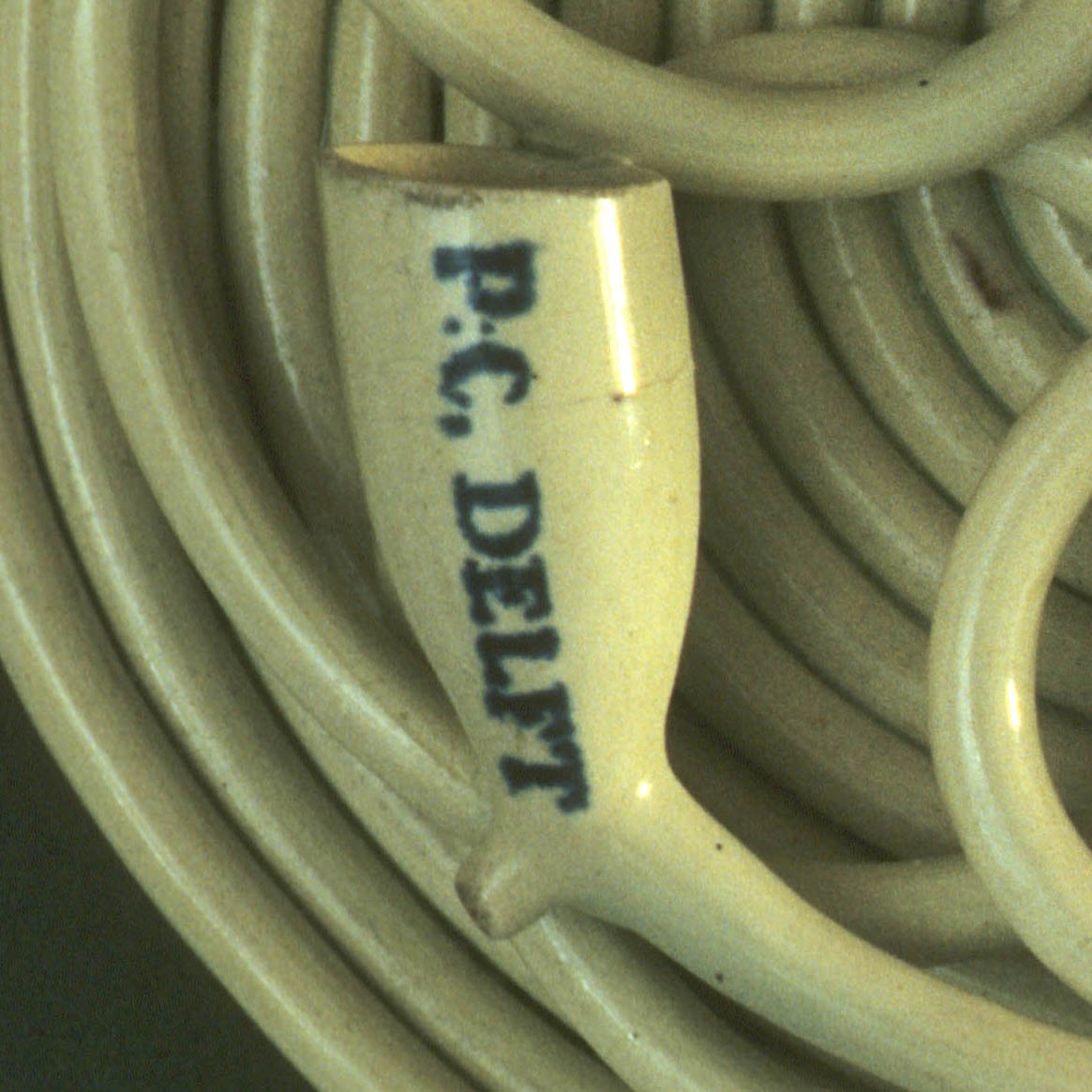

In the Pijpenkabinet, museum for the tobacco pipe in Leiden, there has been a product for years that does not occur in any of Piccardt's written sources, but which nevertheless was produced in his factory.[2] It is a remarkable presentation pipe, which will have been intended for exhibition purposes rather than for use by a smoker. The stem of this tobacco pipe has a length of 7.75 meters and is spirally wound into a flat dish. The last piece of stem is playfully flung over the dish in circular shapes, as if a cake was being decorated by a confectioner's apprentice. The pipe bowl is located at the bottom right of the dish. The maker's signature is remarkable in several respects. In Piccardt's time almost all products were marked on the underside, while with this object the mark was painted in a prominent place on the bowl of the tobacco pipe. The manner of marking therefore implies clearly that we are dealing with a product intended for presentation purposes. A piece intended for the company's showroom, for example, as a test of craftsmanship to master the whitewashing shard with the smooth, transparent, light slightly off-green glaze In other words, the victory over a ceramic-technical problem, namely that of the tension ratio between shard and glaze.

The various spheres of influence within which the Piccardt pipe originated give substance to discussion. The place Delft is so close to Gouda, that achievements from this Dutch pipe maker centre may well have penetrated the Piccardt company. Certainly when we consider that Piccardt continues to improve his "dough" until-near-perfection, whereby especially the pursuit of a white colour gave him a lot of problems. Only after the first quarter of the nineteenth century he achieved good results. It is quite plausible that Piccardt initially sought inspiration from the Gouda pipe makers. After all, the white-baking clay was used there in large quantities and the two-piece press mould was also known there.

However, assuming links with Gouda regarding the clay composition and production method are unfounded. The bowl shape of the Piccardt pipe shows no correspondence with the pipe models that were in production in Gouda in the first half of the nineteenth century. For example, the fire opening here is cut off slightly square, while the edge is also less finely worked than the Gouda counterparts. The manner in which the stem is braided has hardly any comparison in Gouda, although in the eighteenth century Gouda pipe makers produced occasionally a single pipe with so-called wrought stem as a curiosity item. The finish with a cream to green-tinted lead glaze is completely unusual for Dutch pipe makers, so that Piccardt could not have been informed about this in Gouda either. The glazing of Gouda pipes only became fashionable in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. For the Gouda pipe makers glazing of the traditional pressed pipe gives some insurmountable problems. The moulded pipe, which is formed by pressing in a two-part press mould, has a surface that is too slippery, on which glaze does not adhere well. During the firing process in the kiln, the glaze would start running. Moreover, by heating the pipe during smoking, the tension difference between glaze and shard will inevitably lead to hair cracks or flaking.

The remarkable Piccardt pipe strangely shows countless features inspired by the decorative pipes made in Staffordshire. In this famous English potter's town the twisting of the pipe stems is well known, sometimes even meters long stems are twisted in a similar way. Moreover, the glazing of pipes is very commonly used there. The pipes in that region are made of a calcareous cream-ware shard and not of pipe clay as is the case in Gouda. The perfect white English dough of the present pipe must have been produced according to English recipe. Because the English chalk pottery is more porous, this enables better adhesion of the glaze. The two-part mould in which the pipe bowl has been formed would not have been a metal press mould from Gouda, but a more simple plaster or ceramic mould. The mould was apparently present in Piccardt's company and presupposes a certain serial production of pipes, although the durability of such a mould is far lower than that of the Gouda brass press mould. In short, this product exhibits characteristics of the English potter's tradition but, in view of its signature, has arisen in a Delft company in the course of changing into cream wear production.

As far as the date is concerned, the perfect white shard accounts for a placement in the final phase of the development of the English pottery at the Piccardt factory. This must have been around 1830. Then one has the right pâte with a colourless shard and one can properly apply the transparent glaze. That with a complicated ceramic body like this curled tobacco pipe the cracking of the glaze was inevitable, was one of the last problems to be overcome at the Piccardt factory. The tension ratios of shard and glaze are largely solved by this wonderful ceramic object. It has become clear that the initial competitors of the Delft product have given the impetus to the Delft cream-ware, the largest ceramic impulse in the Netherlands in the nineteenth century. This pipe was not only the showpiece of this new achievement in the first half of the nineteenth century, but it is still the tangible testimony to this. However, the long lasting production of glazed earthenware smoking equipment would have to wait until the beginning of the twentieth century and lays again in the hands of the famous Gouda pipe makers. However, it has to be said that the German potters realized this already generations earlier.

A pedigree of this remarkable presentation pipe cannot be given. The pipe was bought in the 1970s in Abbéville, west France, at an antique dealer. According to say, this piece had been in a family of farmers in the region for generations, a dubious indication that one is directly inclined to ignore, not to go on speculation.

© Don Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Leiden – the Netherlands, 1990.

Published in: Maandblad Antiek, XXV/1, June 1990, pp 14-17.

Illustrations

- Tobacco pipe with braided stem in cream ware ceramic with soft green-tinted glaze and blue painted signature "P.C. DELF". Delft, Hendrikus Arnoldus Piccardt, 1820-1840.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 7.448

Notes

[1] M.E. Schram-van Gulik, De geschiedenis en produktie van de aardewerkfabriek de "Porceleyne Fles" te Delft in de 19de en begin 20ste eeuw. Master thesis History of Art, Leiden, 1977.

[2] Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 7.748.