The craze for Abd-El-Kader

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

De rage rond Abd-El-Kader

Publication Year:

2011

Publisher:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description:

About stub stemmed pipes with the bust of Abd-El-Kader made by French pipe factories, with information about the life of the proposed, pipes from different periods including three imitations that this pipe design brought about.

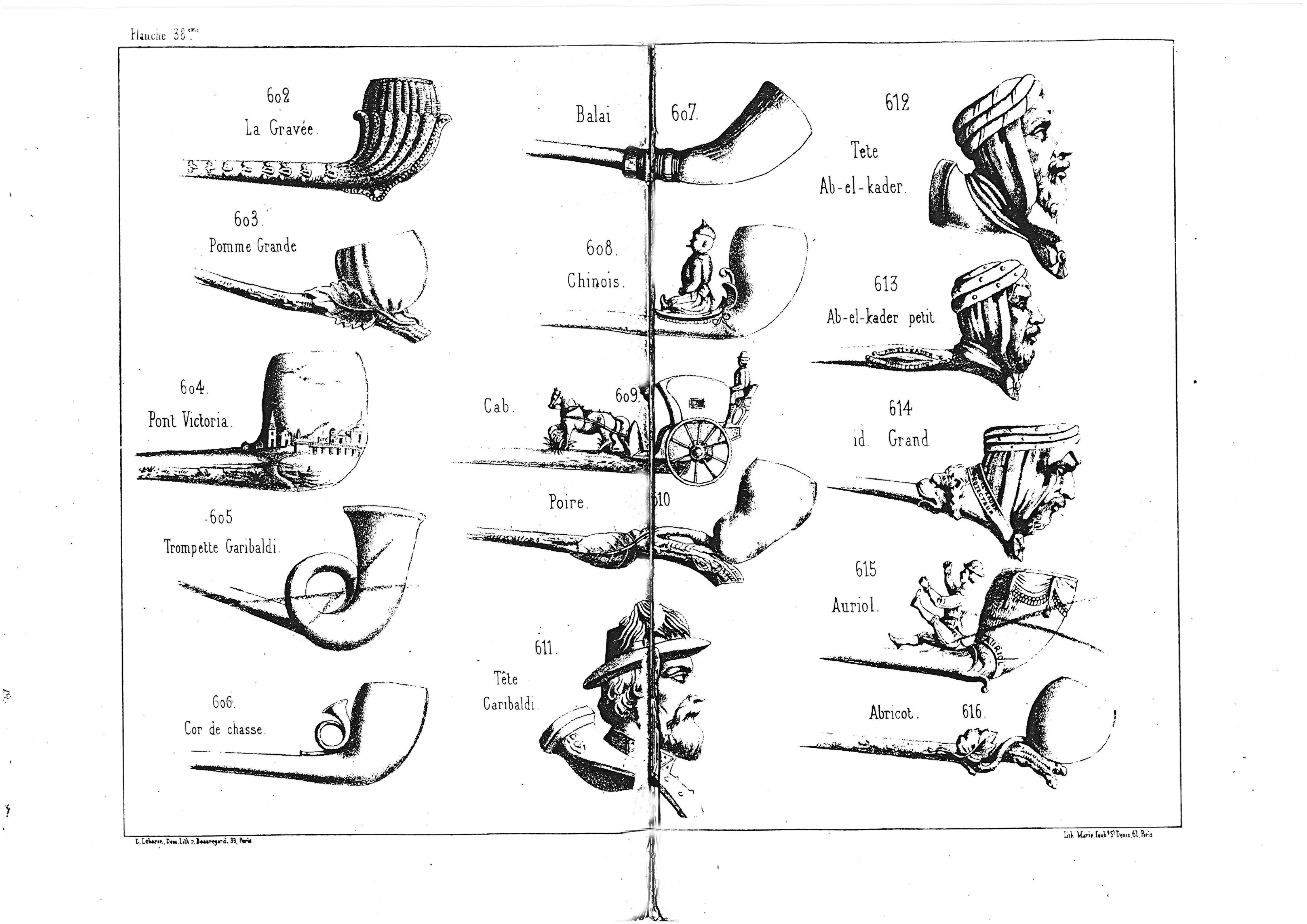

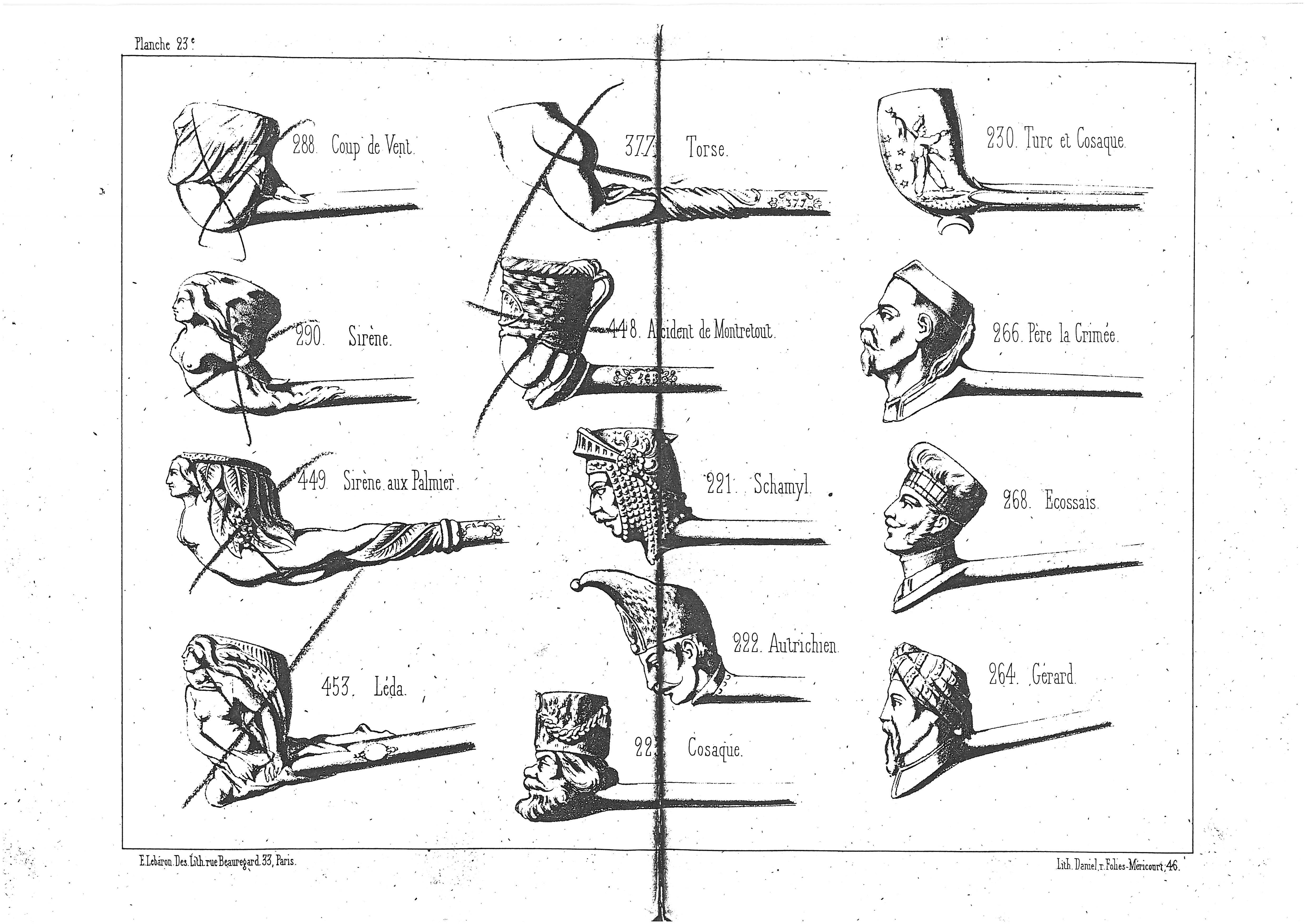

Portraits of exotics are common in the world of the figural tobacco pipe and apparently extremely popular. You cannot view a range of pipes from a pipe factory or you will find sets of man portraits and sometimes even women heads decorated with turbans. That is not surprising, the turban speaks to the imagination, refers to an exotic ambiance and can take many variations. For the pipe manufacturer, the turban is an easy-to-shape part when a design is created. The folds look naturalistic soon, while a relief of embroidery or a piece of stone can give the headgear large variation with a varied effect as a result. In addition, the bowl opening is always easy to place in the head cover.

This article is dedicated to a specific turban personality with smooth shaved face and a small moustache (Fig. 1, 2). Usually the bust of this figure is also shown with skirt collars bordered with a fur lining. Sometimes he is wearing a dagger in the embroidered robe and around the neck he carries a necklace with a coin or medal. The design is characteristic of the 1830s and can be categorized as a figural pipe in full growth. Very specific with this portrait pipe is that the bottom side has not been finished smooth or with a simple ornament, but it is fully ornamented. On this base we see a round face framed by a lion's pelt with the head of the animal above the forehead, the hide of the legs is tied around the stem ending in two drooping claws. The representation of a man dressed in a lion's hide is traditionally the depiction of an invincible leader, someone who has surpassed the king of animals. This image goes back to the mythological battle of Hercules with the Nemean lion. Not only did Roman emperors show themselves in this exotic apparel but tribal chiefs in North Africa as well.

The combination of the Arab person with the Hercules person as a model of strength on the bottom of the pipe bowl has led to misinterpretations. The literature is not unequivocal and there is a great deal of confusion among collectors. Further consideration of the variants of this pipe design and research of the scarce source material has led to new insights. This article provides more clarity on this subject and solves some stubborn mistakes. In addition, it deals with some similar images that are more recent, falling back on this familiar concept. In short, a fascinating interaction with claims, determinations and interpretations.

Attribution and explanation

Numerous attributions have been made about the mysterious person presented in this pipe bowl. In the Encyclopédie du tabac et des fumeurs (Paris, 1975) one speaks of a Roustan, the mameluk and a companion of emperor Napoleon. His name is also written as Roustam or Rustam. However, the magnitude of the book does not appear to be proportional to the expertise of the authors. Thus this pipe is uncritically attributed to Gambier while the name stamp Fiolet is on the stub. The pipe is therefore not made at the most general factory, the Gambier company in the Ardennes, but more west at Fiolet in Saint-Omer. It is therefore also advisable to examine the attribution of the sitter to Roustam. In any case, this false determination has ensured that collectors now generally regard this pipe as the portrait of Roustam.

Fifteen years after the publication of the bulky encyclopaedia, publicist Véronique Deloffre is no longer convinced of the attribution. In her Pipes et Pipiers de Saint-Omer (Saint-Omer, 1991) she depicts a similar pipe and she mentions in the caption that this pipe is known as the mameluk Roustam, but that in reality a sultan is represented. Entirely in line with nineteenth century Orientalism, in which a certain romantic feeling about the exotic Orient takes the upper hand over the factual knowledge of things, the sultan and emir designations are used interchangeably. From Deloffre, most collectors speak of an emir, meaning a noble or even regal title from the Middle East or North Africa. This shifted the determination and thus the target group for the pipe from the French royalist entourage to that of the devotee of exotic.

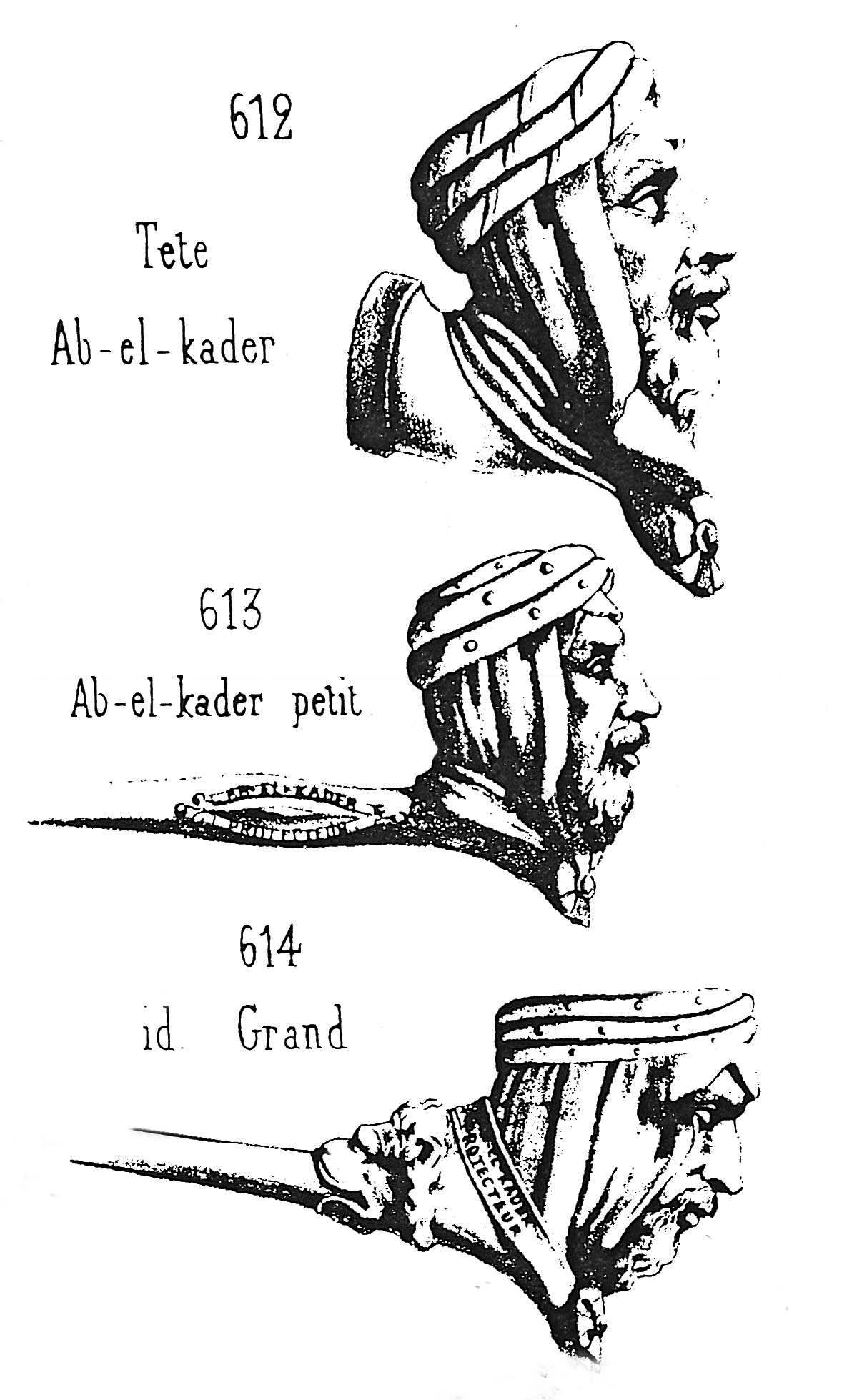

Meanwhile, another twenty years later, the riddle of the attribution has been solved. By comparing all variants, an unobtrusive inscription along the stem edge was revealed on the smallest version of the Fiolet pipe. This indicates what the manufacturer meant with the portrait at the time, because here we read "ABDEL KADER" (Fig. 3). This heading refers to Sidi-el-Hadi Ouled-Mahiddin Abd-El-Kader, a famous leader who fought against the French settlers in Algeria and other North-African territories for fifteen years.

Abd-El-Kader was born in 1807 as the son of a sheikh from the Quadiri Sufi order in Algeria. He followed a training in theology of the Quran and naturally learned religious and literary Arabic. In 1825 he went with his father on a pilgrimage to Mecca where he came in contact with a Caucasian resistance fighter. This man persuaded him to go to Damascus, where he visited the tombs of the prominent Islamic clergy and foremen. In 1830 the French invaded Algeria to colonize the country. They removed de Dey of Algiers, a governor appointed by the Ottoman sultans, and French military administrators took up the service. From 1832 Abd-El-Kader conducted the holy war against the Christians in North Africa and especially against the French with a guerrilla army. This happened first from Algeria, later also from Morocco. His army soon gained reinforcement from the Kabyls, a Berber tribe from the mountainous regions of Algeria, with whom he won countless victories. As a charismatic leader and passionate orator, he succeeded in uniting many tribes in the Maghreb. Due in part to the apostate attitude of the Kabyls, the French finally managed to force Abd-El-Kader into surrender in December 1847 and the Arab leader was imprisoned in France.

The capture of Abd-El-Kader meant a colonial blessing for France. The leader spent the years between 1847 and 1852 in various French prisons, but the political career of Abd-El-Kader was not yet complete. On the occasion of the coronation of Napoleon as emperor Napoleon III, he granted him pardon. The condition was that he would not put up any more trouble in Algeria but would go to Constantinople. Abd-El-Kader eventually withdrew to Broussa and Damascus in Syria. In 1860 he came to publicity again, because he saved countless Christians during a bloodbath that was caused by the Maronites. Doing so he suddenly changed role from a hated opponent of France into a hero. Napoleon III granted him the Grand Cross of the Légion d'Honneur and also a substantial pension. Abd-El-Kader died in Damascus in 1883 after an eventful life.

It is certain that there were sufficient reasons to portray Abd-El-Kader in a tobacco pipe. Initially his face represented that of the heroic rebel who was to be conquered. Thanks to the heroic stories about Abd-El-Kader, the pipe in France was loved by a wide audience that admired the heroic deeds in distant countries about which exciting stories circulated. The new French colony in North Africa with its immense size offered opportunities to many French adventurers. Soldiers and entrepreneurs went to Algeria, so the Magreb was in the news every day in the years 1830 and 1840. From the time of design, probably already around 1835, the pipe bowl of Abd-El-Kader remained a good item for the French smoker who adored these heroic stories. Logically, an increased sale and turnover was made when the capture of Abd-El-Kader was a fact, after fifteen years of bitter struggle. Then the interest gradually ebbed away.

The versions from Saint-Omer

The pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader together with Hercules with lions hide is made in remarkably many varieties, by various factories in France and even beyond. The most complete series and also the earliest of design originates from the Louis Fiolet factory in Saint-Omer. It is a successful design with sufficient bowl space, a solid base for comfortable holding while it is a nicely rounded object that feels comfortable. Fiolet produced the same stub stemmed pipe bowl in the sizes petit, moyen and grand (Figs. 1-3). Especially for figural pipes, offering three sizes of the same image is exceptional. In order to score maximum sales, a wide range of subjects was more favourable than an in-depth supply of the same picture in varying sizes.

In addition to the reported three stub stemmed pipe bowls, Fiolet also supplied a large shop window pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader (Fig. 4) having the same design. This is not a smoking pipe, but an extra-large pipe bowl with a height of more than twenty centimetres, used by the specialized pipe and tobacco shop to advertise the clay pipe of ordinary size. All leading factories produced such presentation pieces. The display window pipe of Abd-El-Kader is similar to the standard smoking pipe, although the modelling of the base is less attractive, because this side would rarely come into view in the shop window. The Hercules mask has now an ugly, somewhat square goatee and the lion skin is modelled too flat. By enlarging a standard pipe bowl into a shop window pipe, the details suddenly appear coarser and less pronounced. Only the embroidered garment is an exception: we see fine relief lines on it. With regard to the details, we have to keep in mind that the display window pipe was meant to be viewed as an eye-catcher from a distance and for that the realized design amply fulfilled. In order to make the pipe more attractive, it was provided with enamel accents, while the oldest ones were sometimes even completely painted with multi-coloured paint in natural colours (Figs. 4, 5).

It is already mentioned that the first Abd-El-Kader pipe was put on the market around 1835. The colonization and thus the battle against Abd-El-Kader had been going on since 1832 and had been current news ever since. Undoubtedly a peak was reached in 1847, the year in which Abd-El-Kader was captured. The popularity of the standard pipe designs will have been a reason for Fiolet to make the shop window pipe as the completion of the series. So that may well have been in 1847. The production period continues over a longer period, as will be discussed below. A few years later, the design of the display window pipe was adjusted. In the presentation piece, the figuration of Hercules at the bottom was not exactly meaningful and, moreover, the shopkeeper could hardly put down the pipe. At one point, the bottom side of the bust was weighted so that a flat, partly hollowed out foot was formed on which the pipe could stand (Figs. 5, 6). That version of the display window pipe is the most common.

It is astonishing that this display window pipe was not only supplied by Louis Fiolet but also by the competitor Emile Duméril, who was located in the same town Saint-Omer (Fig. 7). For the time being, it remains unclear whether the press mould was lent to the competitor or resold at a given moment. Duméril could even have ordered this pipe with its own mark stamped by Fiolet. Whatever the case, these actions do not point to the manufacturers' endeavours for exclusivity of their designs, and that is especially unexpected for Duméril because they had originality high on their banner.

Another, truly beautiful interpretation of Abd-El-Kader was also made by the aforementioned firm Duméril (Fig. 8). Characteristic of the designs of this illustrious factory is that their portraits are usually modest but very specific. Their Abd-El-Kader pipe shows a serene stylization of the face in combination with a simple effect of the clothing on the bust. Moreover, the Hercules head is left out. However, the stem is very subtly designed to end in a cylindrical sleeve. This pipe bowl is more recent and dates probably only in the late 1850s. In the meantime, the Abd-El-Kader bust was well known so that a reference to the sitter with a text was no longer necessary. It is certain that Duméril did not achieve commercial success with this particular variant, in contrast to Fiolet's designs. In fact, this pipe design was launched too late. Duméril connected only to the aftermath of the fad around Abd-El-Kader with this creation. For the smoker then, this version was seen as a romantic youth portrait. It is clear that the popularity of Abd-El-Kader was so great that several pipe factories portrayed the subject. Fiolet, however, seems the initiator and has been followed in its creation in three countries. Other factories came to own designs.

Variants from elsewhere

The enthusiasm for Abd-El-Kader pipe by Fiolet did not go unnoticed by the other pipe factories. The portrait pipe of Abd-El-Kader, with or without the Hercules head, will certainly also be taken into production by smaller French pipe factories. Of these workshops, however, few pipes are known, and among them there are no Abd-El-Kader portraits. The fascinating interaction between the designs of the leading factories and the smaller, mostly locally operating companies has hardly been investigated yet and in the future undoubtedly unexpected examples will emerge.

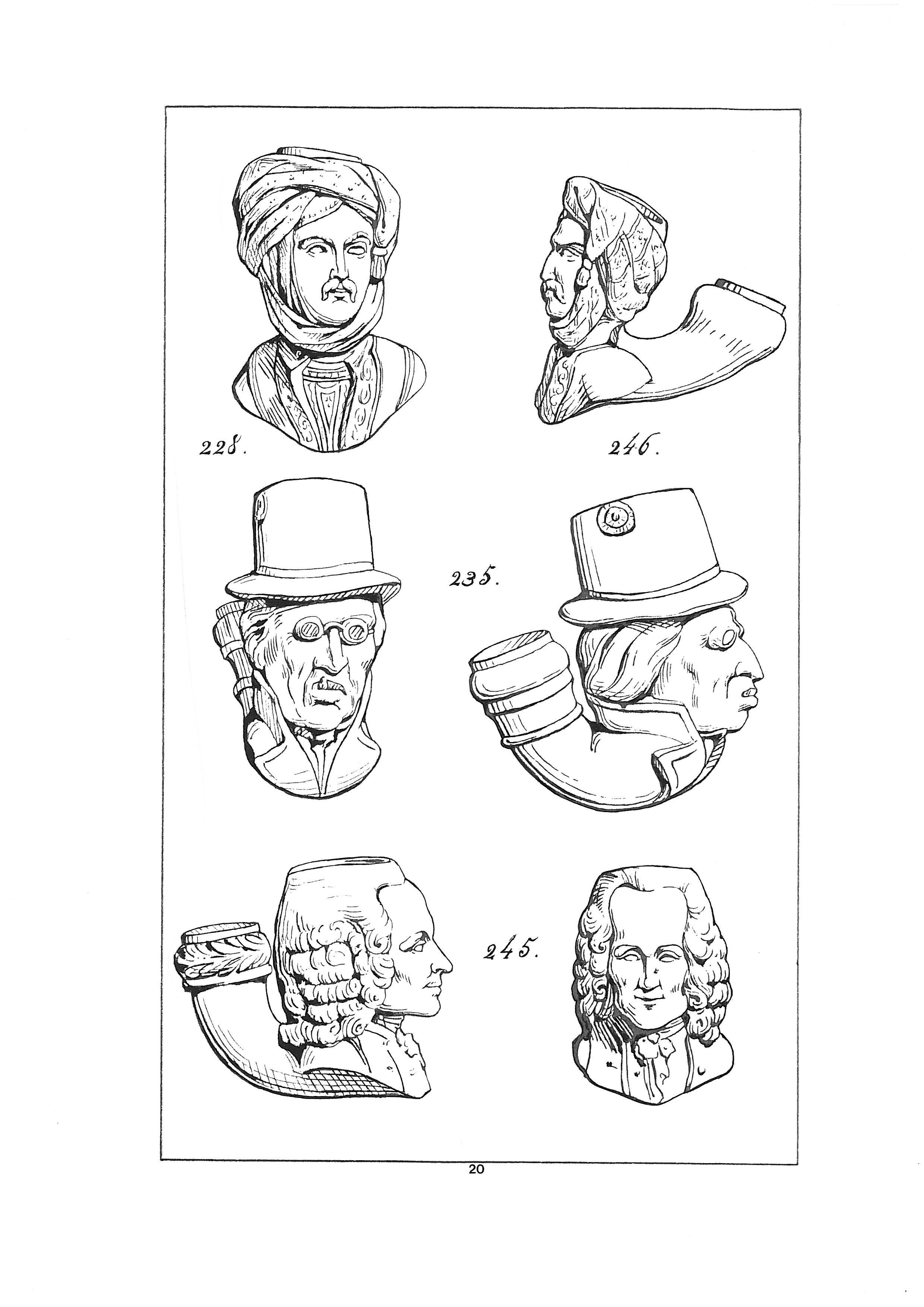

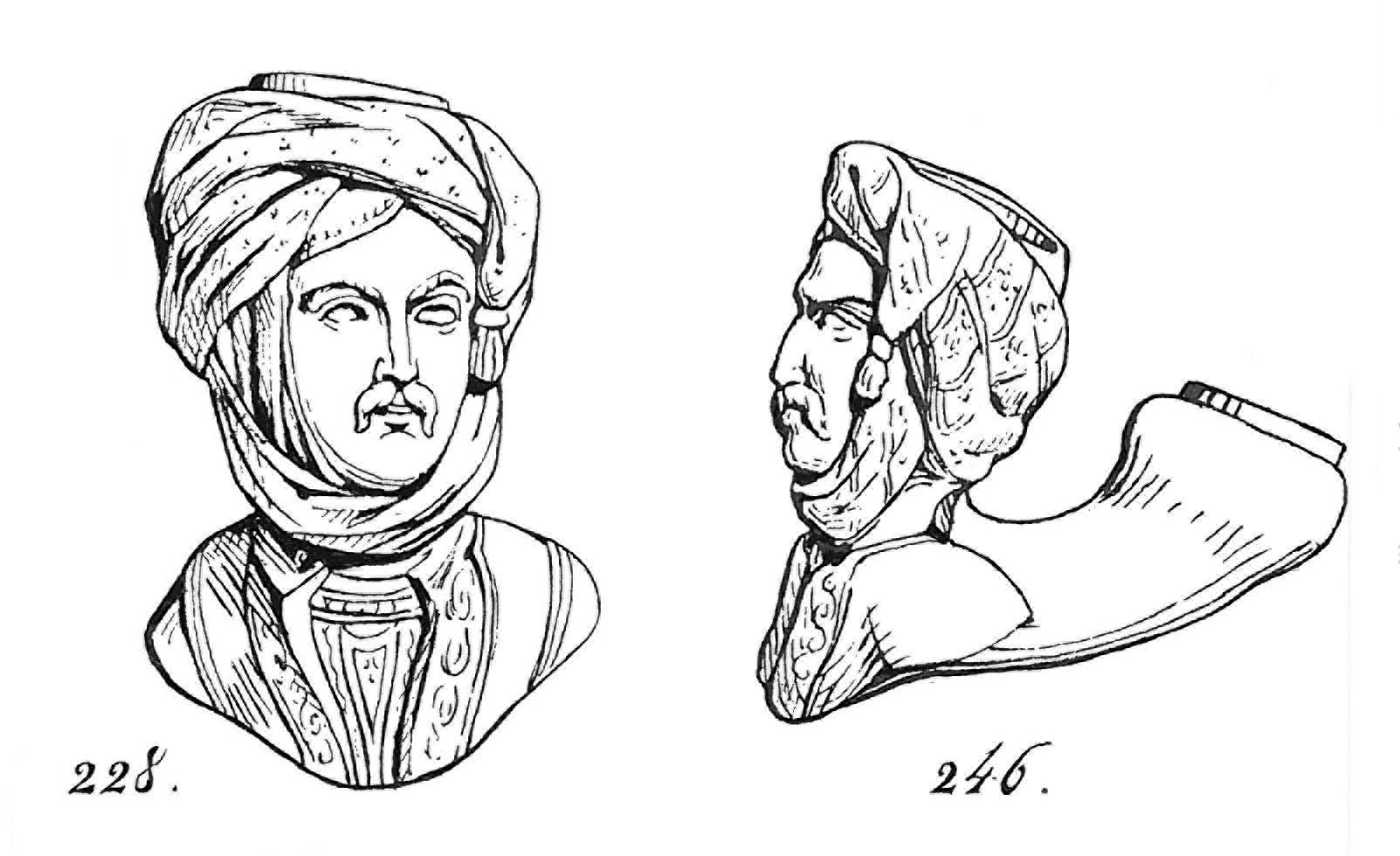

The portrait of Abd-El-Kader, however, was copied freely by other leading French factories. The serene version of Duméril (see Fig. 8) has already been discussed. The company Blanc-Garin & Guyot from Givet describes two pipes with this person in the catalogue of around 1840. The oldest is included under shape number 228 and is a beautiful portrait of the still youthful Abd-El-Kader, modelled according to her own insight (Fig. 9). With this bust, a flamboyant cloth-like scarf is draped around his head, leaving only the face with a moustache visible. The bust is smooth on the underside. About two years later, the same design will be launched in smaller size under shape number 246 (Fig. 10). Here too, a second size underlines the great popularity of the subject. The third version of Blanc-Garin is included under shape number 274 and is called "Abdel-Kader nouveau" to distinguish it from the former. Unfortunately, this design is not shown in the catalogue. We can assume that it was an updated design of a somewhat older person. Finally, in a later time, Blanc-Garin created a shop window pipe, which will be discussed in the next section.

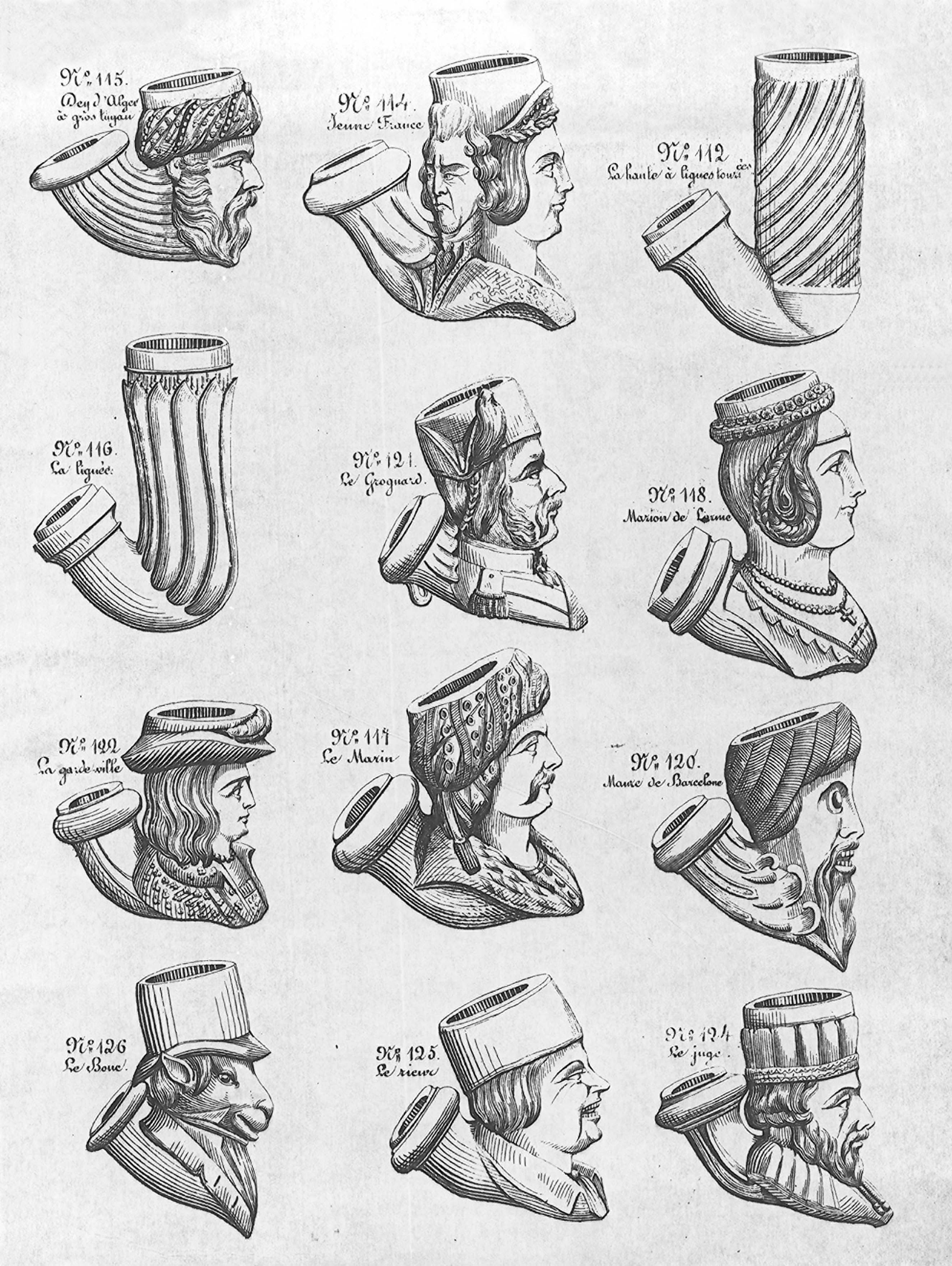

As far as the foreign factories are concerned, we see that only the Fiolet version is reproduced. No less than three centres have copied this design. In the Belgian Meuse region, the Wingender-Knoedgen company from Chokier copied an Abd-El-Kader pipe bowl from Fiolet depicted in their catalogue of about 1850 (Fig. 11). Below shape number 117 we see this portrait, interestingly enough, the Hercules head is omitted. Apparently Wingender saw a design with good sales opportunities in this pipe shape, but made an adjustment for the sake of the market. The reason must be that Wingender-Knoedgen sold its products mainly in Belgium and there was no commercial value for the offering of a French political figure. The name of the image was simplified to le Marin, not a very fanciful indication given the very specific depiction. A name like le corsaire or the pirate had been more appropriate, for instance. The turban does not fit well with a sailor, unless it is an oriental pirate.

The design of the Abd-El-Kader pipe from Fiolet has become even more widespread. In the German Westerwald, Fiolet's pipe design has been adopted unchanged, albeit with a somewhat less subtle detailing. This corresponds with the image we have of the industry in this German area where copying with a certain simplification was standard. A beautiful version of this pipe has emerged as an excavated pipe (Fig. 12). A second example can be found in the catalogue of Müllenbach und Thewald from Höhr under shape number 230.

In Ruhla in Thuringia in Germany the Abd-El-Kader version of Fiolet was also followed, processed unaltered into a pipe (Fig. 13). The unscrupulous copying of pipe designs was customary in Ruhla, this region was more of a production centre than a place of artistic merit and originality. The Ruhla factory didn’t work with press moulded pipe clay, but with a fine yellow-tinted or pink-red slip casting clay instead. Such products carry the exclusive name siderolith, to emphasize the fineness and particularity of the material. They were finished with a solid paint in colour ranging from dark brown to bright red. The hollow-walled, light-weight products have a strong resemblance to the luxury press meerschaum and the sales price was far above that of the clay pipe.

It is clear that the Fiolet firm had a lot of influence with its Abd-El-Kader portrait pipe. Incidentally, copying applies mainly to those factories that did not design themselves but based themselves on the products of other companies. The high-profile French pipe factories employed a designer themselves and made sure that they served the market with original designs.

Updating the design

From the above mentioned biography of Abd-El-Kader it was already revealed that in 1853 he was granted pardon and that release from prison followed. France was mild and Abd-El-Kader reappeared in publicity, no longer as an opponent and prisoner but now as a rehabilitated person. Manufacturers who wanted to exploit this actuality had to come up with a new design because it was necessary to adjust the portrait of Abd-El since the years gone by. During his imprisonment, he lost his facial features of a youthful warrior, most apparently in growing a beard. A revised design of the pipe with an updated portrait was therefore desirable.

The most impressive is the creation of the company Vve. Blanc-Garin who made an imposing shop window pipe with a beautiful bust of the much older Abd-El-Kader now with beard (Fig. 14). Very successful is the design of his facial expression that exudes an exasperated fatigue framed by the naturalistic beard. With this design a lot of attention goes to the turban, which is beautifully modelled in a subtle relief. Finally, the product is extremely suitable as a shop window pipe because of its flat standing base, fully retaining the appearance of a tobacco pipe, partly due to the addition of a conspicuous stub stem. This stem is nicely decorated with neo-Renaissance motifs with scrolls, historical ornaments that were very fashionable at that time. As a critical note, it should be remarked that these Western motives have no relationship with the depicted person. Instead, the Muslim art has so many ornamental design to offer. Such a richly decorated stem has remained a one-off and we will no longer see it in clay pipes.

This impressive presentation pipe must have been conceived around 1855, when Blanc-Garin was still a factory of importance. After these years, the company's turnover will decline rapidly. The press mould of this striking display pipe was probably made in Paris in consultation with a sculptor and a skilled mould maker. The work is in fact a-typical for the mould makers of the factory in Givet that provided the regular press moulds. This multi-part brass mould was later transferred to Gambier where the production was continued for many years. This is why we encounter the pipe with the mark stamps of both factories, copies of Gambier being more common. In addition to white and red clay, the pipe is also supplied in a subtle bronzed version (Fig. 15) and even in an exaggerated coloured version with a paint in multicolour enamel (Fig. 16).

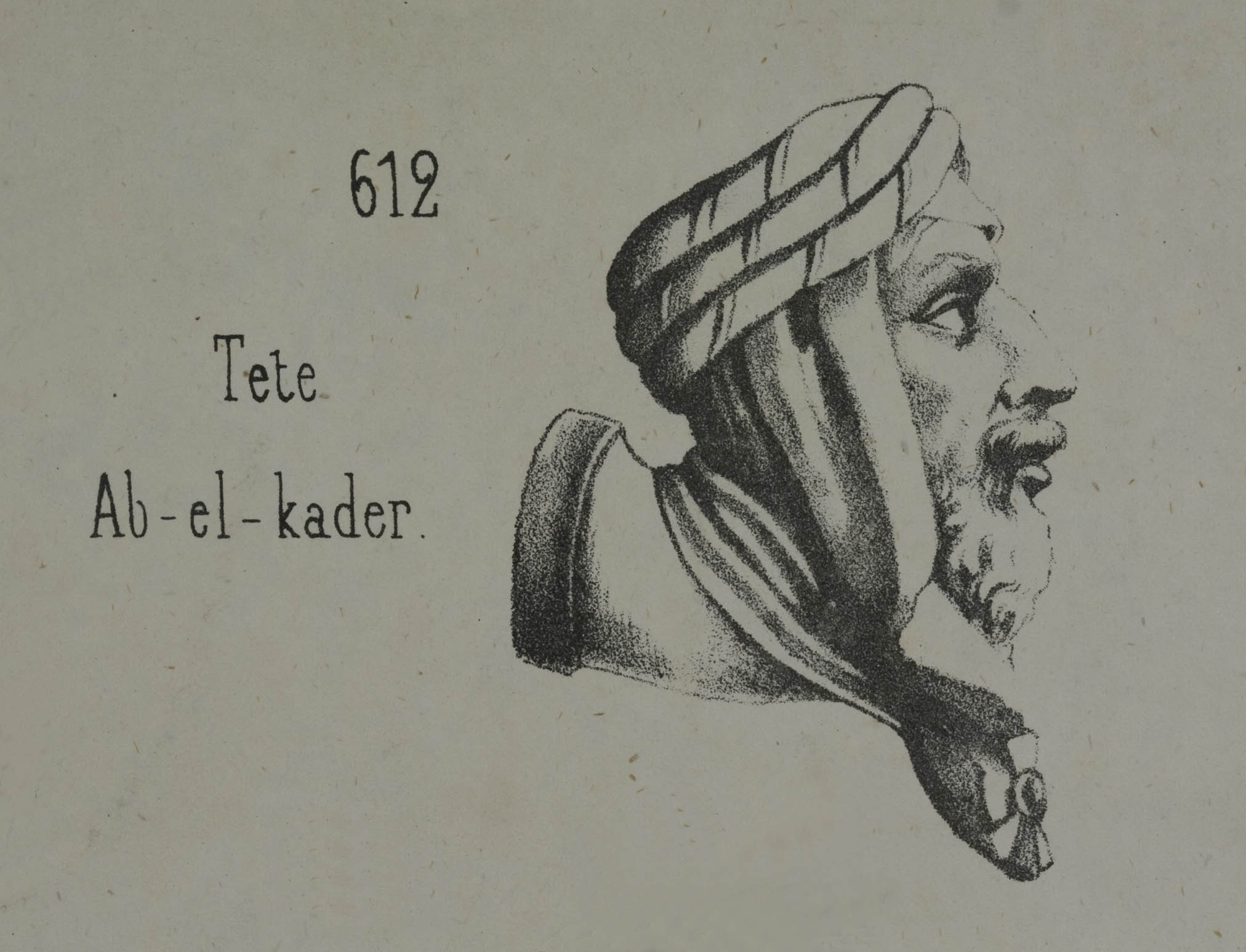

The Gisclon company from Lille contributed in a different way to the continuation of the Abd-El-Kader craze. They came simultaneously with three portrait pipes in which the warrior is depicted as a laureate protector, as the stem inscription states (Fig. 17). Gisclon modelled a portrait similar to the one by Blanc-Garin of a bearded man with the decoration of the Légion d'Honneur obtained in France at the base of the pipe bowl. Gisclon is unique in offering the same design often in multiple sizes and versions at the same time and that also happened here. Shape 612 is the stub stemmed version, the two other pipes have a clay stem and differ in size. There are two stem markings, one of which reads "AB-EL KADER FANATISME VICTIMES PROTECTEUR" (shape 612), or in more comprehensible phrasing: Ab-El Kader, protector of the victims of fanatism, mainly related to the character of the person (Fig. 18). Opposite is "AB EL KADER PROTECTEUR DES CHRETIENS DE SYRIE" (shape 613 and 164) which refers to his heroic behaviour in Damascus. The launch of these three pipe shapes is in line with the salvation of the Christians by Abd-El-Kader in 1860 and caused a revival of his popularity again.

Gambier played an insignificant role in the worship of Abd-El Kader, quite characteristic for the factory. The range of Gambier is usually more moderate and consciously kept away from a specific political colour. Only one pipe shape is dedicated to the emir (shape 657). It is a stemmed pipe but an exceptional one because it is made in a small size (Fig. 19). This Abdel-Kader mignon shows the same bearded figure, but now the head is mainly hidden in his tagelmust or Alasho veil, the typical Sahara combination of cloth headgear and scarf. Whether Kader was really wearing this kind of headdress still is the question, for horse riding militants in the North-African dessert it was at the time certainly a practical and common kind of clothing. The stem set of this pipe is gracefully decorated with a stylized leaf motif, a decoration that is not very common in portrait pipes.

Between 1860 and 1883, the year of Abd-El-Kader's death, the interest in pipes with his portrait will have gradually disappeared. The person fell into oblivion, the exciting stories about the Algerian adventure were eclipsed by more current news items such as the Franco-German war and the fall of Emperor Napoleon III. The regular smoking pipe of Abd-El was soon no longer sold. On the contrary, the shop window pipes retained a certain value as eye-catchers. At Duméril and Fiolet, no new designs were put in place. It seems that their shop window pipe was still made even though the obsolete reference to the actual person was replaced for a new name. During the Second Empire, several people were eligible for being linked to the bearded Magreb portrait, which will be discussed later. The Gambier firm replaced their Abd-El-Kader showcase pipe twice for new designs, namely for a portrait of Diane de Poitiers to a historical image and for a Dionysus figure copied from a classical sculpture. In addition, it seems that the imposing press mould of Blanc-Garin was used again in the 1880s, perhaps to tie in with the death of Abd-El-Kader.

The consequences of the fad

The popularity of the Abd-El-Kader pipe contributed to the interest among smokers to smoke from portrait pipes of figures with turbans or veil. From 1830 onwards, such designs are a permanent part of the assortment of each pipe factory. There is a great variety that often makes it difficult for us to interpret the portrayed, partly because we have limited knowledge about the importance of the personalities at the time. It is certain that the smokers will have been puzzled in the past as well and the manufacturer will have made this to his advantage. In the end, the more general the image was, the sooner it connected to the buyer's line of thinking. In this section three similar designs are reviewed that are each related in their own way to the mania about Abd-El-Kader.

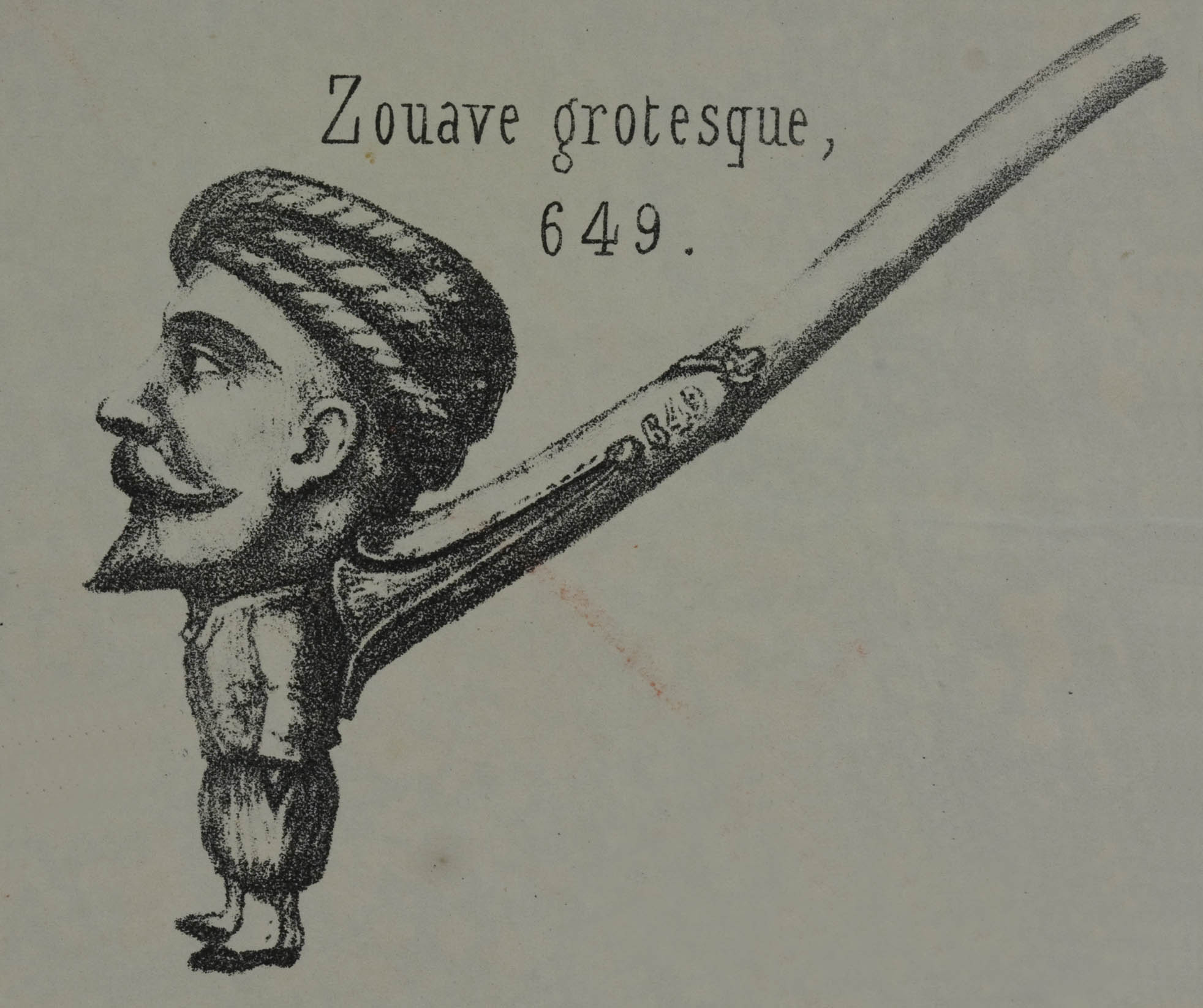

The first and most powerful look-alike is the portrayal of Roustam, the person mentioned in the introduction. Here too it is a turban, although he has an even more elegant face than Abd-El-Kader. Roustam Razza, as he was called in full, was born in Tiflis in Georgia and taken to Egypt as an orphan to work as a slave at a young age. In 1798, the Sheikh of Cairo offered him to emperor Napoleon, who, after completing his Egyptian adventure, took him to France a year later. There Roustam quickly became part of the guard of the corps de l'empereur and served the emperor as a personal valet de chambre until the year 1814, the moment Napoleon was banished to Elba. Roustam then married mademoiselle Douville and remained in Dourdan, her birthplace near Paris, until his death in 1845. Roustam became known by his Mémoires, that are known for the difficult language but were widely read because of the wonderful disclosure of the imperial court secrets. Only in 1910 a readable folk edition was published of these memoirs. Roustam also owes his popularity to his lovable role as the servant of Emperor Napoleon in various theatre plays. There his character acted as an elegant person complete with turban and small moustache.

The firm Dutel-Gisclon from Montereau, founded in 1838, launched a Roustam pipe around 1860 whose concept unmistakably goes back to the Abd-El-Kader creation of Fiolet (Fig. 20). The pipe bowl is registered under shape number 521 with the name Rustan and that indication is also mentioned on the stem of the pipe, as Fiolet had done before with the Abd-El-Kader inscription. Although clearly inspired on the Abd-El-Kader pipe, this pipe bowl still follows the appearance of the imperial houseboy, especially in the almond-shaped face. For the collectors that pipe might have resulted in the incorrect attribution of the other much older Abd-El-Kader pipes.

The company of Edmé Gisclon from Lille, set up by the brother-in-law of Dutel, also capitalized on the popularity of the day and even produced two Roustam pipes. In addition to a standard size stub stemmed pipe bowl, there was a smaller version under shape number 489 (Fig. 21). It is a similar representation of Roustam as Dutel made and it is even the question which of the two manufacturers was the first. Interestingly enough, this pipe bowl is renamed in the Gisclon catalogue from shortly after 1875 to tête jouet Turc. With this general name the pipe was suitable for a wider audience because the relationship to the imperial entourage after 1870 had to be over. By renaming the pipe in the catalogue to an anonymous image, the manufacturer cleaned his designs from royalist features.

We may suppose that the craze for Abd-El-Kader was over its peak in 1853 and that during the Second Empire there was instead a renewed interest in Napoleon and his sympathizers. In fact, every Abd-El-Kader pipe could have been renamed Roustam during that period, although the facial features of Abd-El-Kader did not fully comply with it. Moreover, the Hercules head had no logical relationship with the Emperor's valet. However, it remains unclear how critical the consumer at the time was with regard to the portrayal. Presumably the sales pitch of the shopkeeper was soon accepted for true and so one image was sold for the other.

In addition to the look-alike in the person of Roustam, the double-headed design of the original Abd-El-Kader pipe by Fiolet was used as inspiration for a new portrait. The best example of this is a pipe design by Gambier who has a famous lion killer as subject. These pipes have the same double portrait as starting point: the bust of a man with an attached circular portrait underneath, in this case not of Hercules with lion hide but a real lion's head. The text around the animal head indicates that it is a popular folk hero from the mid-nineteenth century.

Cécile-Jules-Basile Gérard, who was nicknamed Le Tueur de Lions, is depicted in the pipe bowl. Gérard was born in 1817 in the town of Pignans in the Var department. According to the book Le Tartarin by Alphonse Daudet, he would have started as a hunter in the casquettes in his own region. Subsequently, he entered service in the North African riders regiment at a young age and proved to be a fearless and very skilled shooter. In eleven years he killed no less than 25 lions, which meant a plague for Algeria. In 1858 he published a book entitled Le Tueur de Lions, in which he pleaded for setting up a more organized lion hunt. Gérard died in Africa in 1864 when he was dragged into the stream when crossing a river.

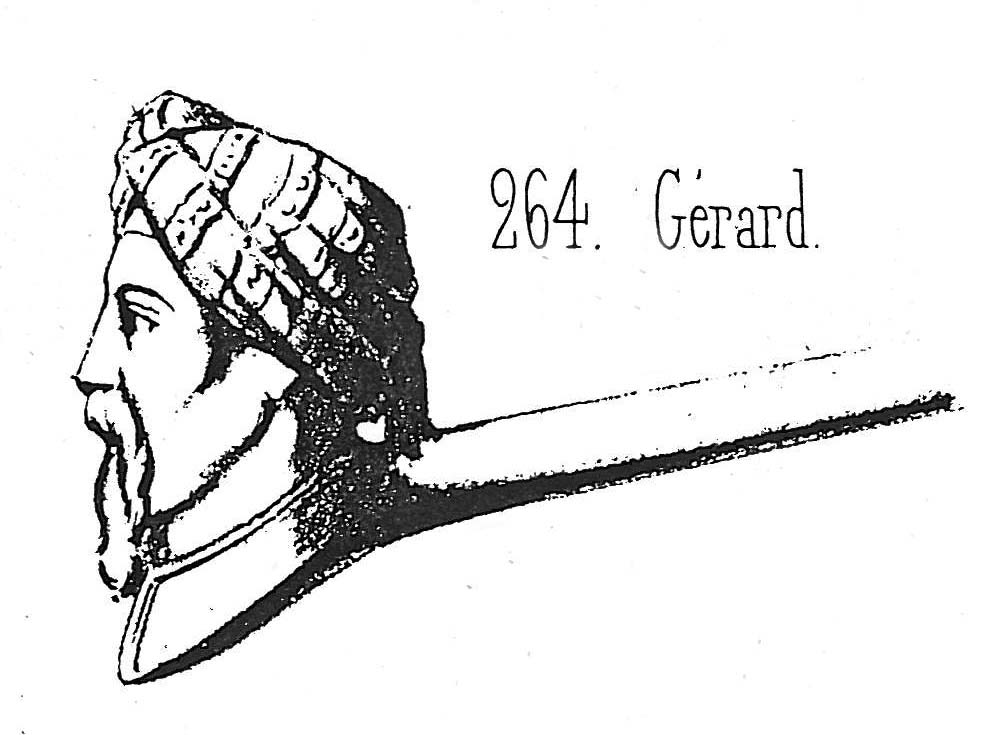

In terms of subject matter, Gérard was particularly suited for a pipe because his portrait would appeal to a wide group of smokers. For that reason, production at Gambier was appropriate, because that factory always sought a general popularity in its decorations. Gambier honoured Gérard with two pipes. The stub stemmed pipe bowl with shape number 896 was executed first, probably in the year 1866 (Fig. 22). Two years later, the more popular stem version came on the market under shape 219 (Fig. 23). Both portrait pipe bowls show Gérard in the same way: a bust of a turbaned man with a moustache and a little goatee. The large version has the text "GERARD LE TUEUR DE LIONS" for identification around the lion's head. In the smaller stem version only the lion's head is shown. This lion's head was, moreover, sufficient for the association with Gérard, because his heroic deeds evolved to mythical proportions and were very appealing to the people's imagination. They gave him an immense, short-lived popularity.

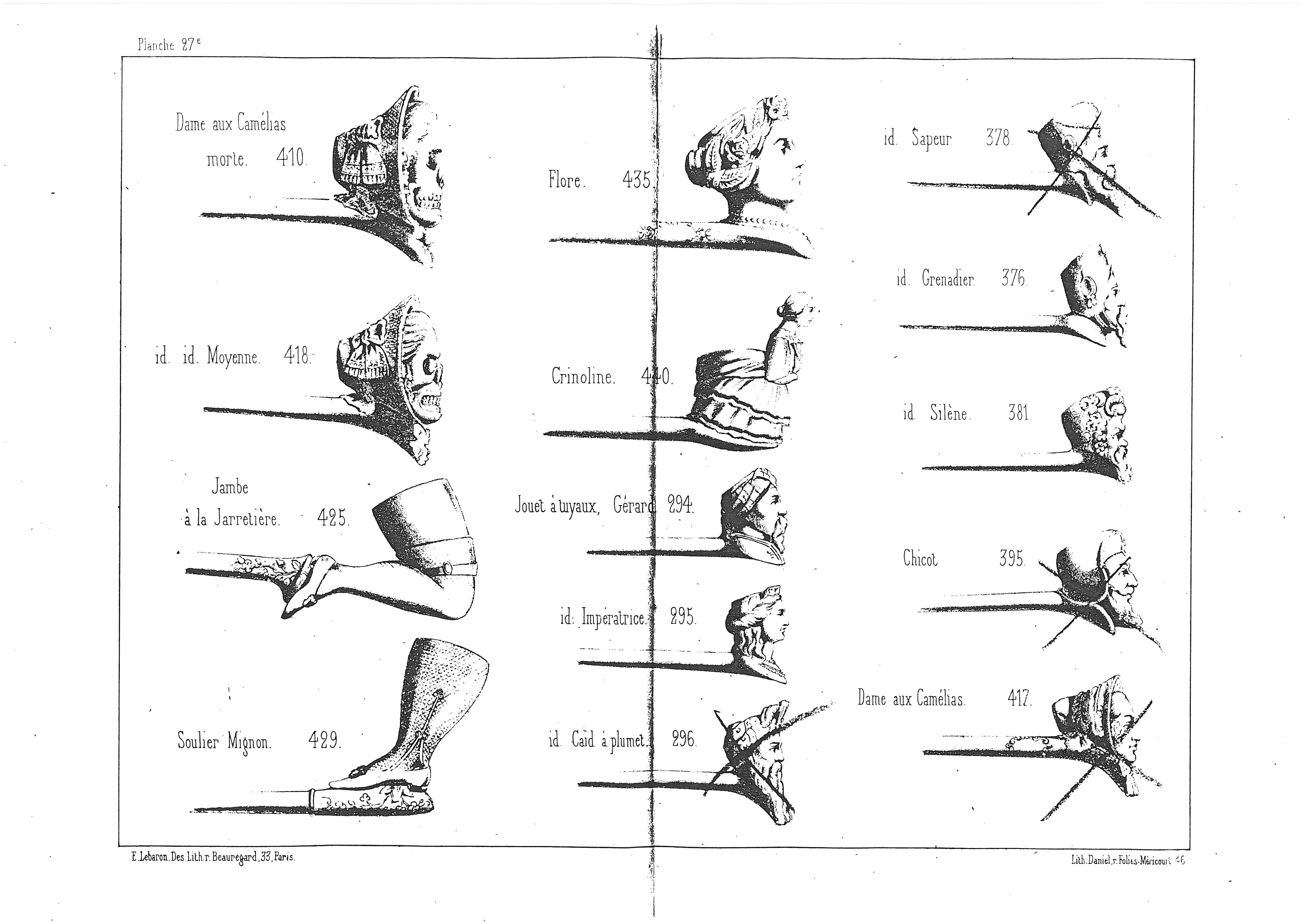

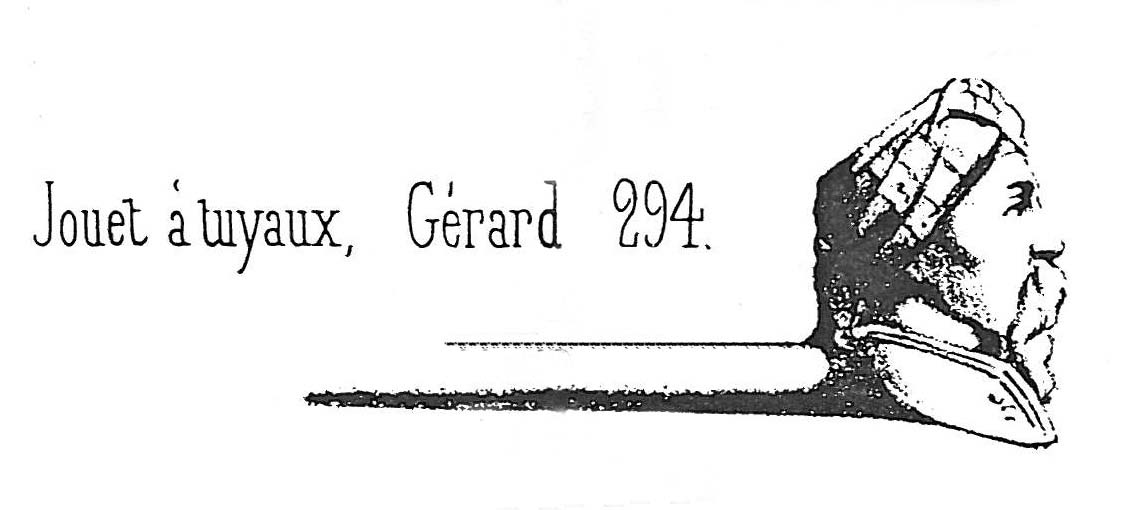

The North African adventure initiated with Abd-El-Kader and succeeded by Gérard in another way, was picked up by other factories as well. Gisclon gave the popular folk hero its own pipe: a stem version under shape number 264 and a smaller Jouet à tuyaux Gérard under shape number 294 (Fig. 24). The subject Gérard must have been copied by smaller factories, although examples of such pipes have not yet surfaced.

The third and most long-lasting craze of a turbaned figure is that of the Jacob pipe, a bearded version that does not show a double head but in which two rectangular shields with inscription are arranged on the underside. I devoted an extensive article to this pipe earlier.[1] The Jacob pipe originated in the 1860s and will remain in the making until the end of clay pipe production. In fact, it is an indirect follow-up to the fad for Abd-El-Kader. As a belated and popularized form of orientalism, the Jacob pipe refers to an existing popular healer dressed in exotic clothing. Meanwhile, the target group for the figural pipe has changed drastically: between 1830 and 1860, the appearance of the figural clay pipe collapses quickly. From a luxury item with a mostly literate look it gradually becomes a popular article affordable for a larger group of smokers. The Jacob pipe fully complies with this trend and it is not surprising that that shape has not remained free of speculation about who is meant to be, how the smoker saw the pipe at the time and especially what the collector thought of it later.

In conclusion

The large number of pipe designs of Abd-El-Kader, whether or not combined with the Hercules head, proves how popular this image has been. Four companies even produced a shop window pipe of this portrait. In addition, the considerable number of preserved specimens is an indication of the enormous circulation at the time. Since no other portrait has been used as frequently as pipe design before 1860, we may assume that the Abd-El-Kader pipe was the first to lead to a craze among smokers.

The general popularity can be explained from the topicality of the North African adventure which France plunged into in 1832 and all illustrated magazines eagerly followed. The craze was fuelled by a growing group of politically and socially committed smokers who chose this topic because it was in line with their world of interest. They see the pipe as a mascot for the colonial expansion or as an illustration of exciting stories around the depicted person. The peculiarity of the worship around Abd-El-Kader is that his career, in addition to the fight against the French, took unexpected turns, which kept the general attention on him. Successively these are the imprisonment, the grace with release as a result and finally the salvation of the Christians and the granting of the Légion d'Honneur. Finally, there was the commemoration around his death. In the portrait pipe we see these phases of life in the aging of the person. An exception to this is a portrait of the youth that is brought by Duméril as a nostalgic item. The different designs come about under pressure from the consumer who always expects an updated presentation.

When the craze faded away the manufacturer attempts to hold the market with new pipe designs. The first option is to find a new target group for the existing pipe shape by connecting it with a new person and consequently a new name. The second option is to unleash a mania around another person, while retaining the successful concept in order to guarantee the smoker will follow. In the first case the existing press mould remains in use, the second option necessitates a new design. The Roustam pipe bowl and Gérard pipe were quoted from both examples, the first being a look-alike that later also came onto the market as an adapted design. The second also shows a double face but then with a different subject. Both pipes are intended for a new target group.

The pipes, but especially the pipe catalogues, teach us that the choice of a design was based on a personality widely known from current events. When selling in the pipe store, both in the big cities and in small places, the pipe sometimes comes apart from the intended sitter. The sale of an existing portrait pipe for a general representation of a North African emir or even for a completely different person can be very convenient for the retailer. As a result, unexpected attributions arose in the past. In addition, it remains an open question how closely the customer looked at the image on his smoking equipment. Was it really important that the pipe represented exactly what he had to represent or was it the general concept of the tobacco pipe? Finally, the underlying motivation of the smoker for making his choice in the pipe shop stays completely out of sight for us after one and a half century. That image is especially shadowy because we do not know what the smoker knew about current events in the world or how much he wanted to express his opinions. Many pipes will have been sold with a fantasy story, in the eyes of the client the historical accuracy did not matter.

The figural pipe of Abd-El-Kader is illustrative for the development of the figural pipe in several respects. With its wide variety of depictions it shows how versatile an illustrious warrior can be portrayed. Later it may happen that this depiction gets a different name to be more saleable. That ultimately caused confusion. For the current collector, in fact the circuit where these type of effigy pipes are now circulating, it is a challenge to discover the true meaning of the depicted historical person but also to place this in a time perspective in which the attribution can change over time. This article illustrates those aspects of the life of a figural pipe and will, I hope, be an incentive to interpret other portraits more carefully.

© Don Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Amsterdam - the Netherlands, 2011.

Illustrations

- Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader in large size. Saint-Omer, firme Louis Fiolet, 1835-1855.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.512 - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader with middle size. Saint-Omer, firme Louis Fiolet, 1835-1855.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.513 - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader with small size, along the cuff inscribed "ABDELKADER". Saint-Omer, firme Louis Fiolet, 1835-1855.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.249 - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader with on the base the depiction of Hercules. Multi-coloured paint. Saint-Omer, firme Louis Fiolet, 1845-1855.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 13.668 - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader, the base partly flattened to stand. Multi-coloured paint. Saint-Omer, firme Louis Fiolet, 1845-1855.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.281 - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader, the base partly flattened to stand. Black baked pipe clay. Saint-Omer, firme Louis Fiolet, 1855-1875.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 8.144 - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader, the base partly flattened to stand, white pipe clay with traces of paint. Saint-Omer, Duméril Leurs & Cie, 1855-1875.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.246 - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader. White clay with coloured enamel. Saint-Omer, Duméril Leurs & Cie, 1855-1865.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 20.274 - Tobacco pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader. Brown coloured moulding clay. Ruhla, shape 22, 1835-1870.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 8.334a - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader as a young person. Givet, Blanc-Garin & Guyot, 1835-1850.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.360 - Catalogue illustration of Abd-El-Kader pipe without the Hercules depiction. Chokier, Wingender-Knoedgen, 1845-1850.

Amsterdam, documentation Pijpenkabinet - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader. Germany, Westerwald, 1850-1880.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.095 - Catalogue illustration of Abd-El-Kader as a young person. Givet, firm Blanc-Garin & Guyot, 1835-1845.

Amsterdam, documentation Pijpenkabinet - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader. Givet, Vve. Blanc-Garin, 1855-1860.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 8.060 - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader in imitation bronze paint. Givet, Vve. Blanc-Garin, 1855-1860.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 11.582 - Showcase pipe with the bust of Abd-El-Kader in multi coloured enamel. Givet, firm J. Gambier, 1870-1880.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.280 - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader with medal and stem inscription. Lille, Edmé Gisclon, 1860-1870.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 19.195 - Catalogue illustration of Abd-El-Kader. Gisclon, Edmé Gisclon, 1870-1880.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 726 - Tobacco pipe with portrait of Abd-El-Kader, uncommon mignon version. Givet, firm J. Gambier, shape 657, 1855-1870.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 13.226 - Tobacco pipe with bust of Abd-El-Kader as Roustam. Montereau, Dutel-Gisclon, shape 521, 1870-1875.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 20.415 - Catalogue illustration of Roustam depicted as a Turc. Lille, Edmé Gisclon, 1860-1875.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 726 - Tobacco pipe with bust of Gerard le tueur des lions. Givet, firm J. Gambier, shape 896, 1865-1880.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 8.391a - Tobacco pipe with portrait of Gerard le tueur des lions, stemmed version. Givet, firm J. Gambier, shape 219, 1865-1880.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.135 - Catalogue illustration showing the bust of Gerard in small so-called jouet size. Lille, Edmé Gisclon, 1870-1880.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 726

Notes

1. Don Duco, De Jacobpijp, een eeuw lang de populairste, Amsterdam, 2010.