Porcelain figurals, not always an original inspiration

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Porseleinen figuurpijpen, niet altijd een originele inspiratie

Publication Year:

2017

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Description:

Discussion of more than twenty figural porcelain pipes from the nineteenth century illustrative of the interaction between designs in porcelain and in clay.

The interaction between porcelain manufacturers and makers of clay pipes has never been the subject of an article. This has to do with the nature of these two materials that differ so much. Clay pipes are simple and primarily utilitarian from the beginning until the nineteenth century. Their design is entirely focused on use and comes in qualities from simple and coarse to refined. Only the shape has been the inspiration for pipes of other materials, not the decoration. Tobacco pipes made in porcelain are of a completely different order. They only came into existence in the eighteenth century with the rise of European porcelain production and were initially a rare and extremely luxurious item. They were made in a limited edition intended for the most sophisticated customers. In first instance, it is not so much about the use as it is about design and painting. The figural representations dominate eighteenth-century porcelain pipes: human heads, even some animals. Due to the nature of the two materials, until around 1800 there was hardly any interaction between the clay pipes for the average smoker and the luxury good of porcelain intended for the spoiled customer.

After the French revolution and the Napoleonic era the situation will change drastically, the nineteenth century brings major changes. Both industries are enlarging their workplaces and increasing their production. They both look for new designs to boost sales. With the manufacturer of clay pipes, interest arises for figurative pipe bowls, here too mainly human persons. This movement starts around 1820 and will have a considerable impact for more than a century. At the same time, the porcelain factories are broadening their market offer as well by paying more attention to the tobacco pipe that is primarily intended for use. They are developing a new type, the so-called stummel, an oval-shaped pipe bowl directly derived from the Gouda clay pipe, but with a short stem. A refined painting is applied to it as a decoration, whereby porcelain painting takes a high flight (Note 1). In the margin the figural line continues, although it remains modest. The original element of luxury is going to be simpler and strongly focused on serial production. It is logical that there are now connections between the two sectors. The product expansion in both branches of industry created a clear overlap. This article interprets these movements on the basis of a series of remarkable and often rare porcelain pipes that prove the interactions between the two disciplines.

Napoleon sets the trend

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the two industries of clay pipe production and porcelain wares, are miles apart in terms of working method, product and customers. So, we cannot noticed any interaction between the two. It is about bulk goods for daily use versus prestigious quality products to show off. The first example of a luxury product from the porcelain industry that is influenced by the clay pipe factories is a beautiful portrait pipe with the bust of Emperor Napoleon I. The depiction presents the emperor with his characteristic transversely placed bicorn. To complete this portrait his bust is also shown, with the green uniform of the Chasseurs of the Imperial Guards, complete with epaulettes and military decorations. These elements contribute to the dignity of the emperor. In addition, the bust shows characteristics of the Empire style that make this object modern and fashionable, typical for a leading porcelain manufacturer. An effigy pipe with such an explicit bust had not been produced before. The portrait in question is modelled by the designer Johann Daniël Schöne at the Königlichen Sächsischen Porzellan-Manufaktur in Meissen (Note 2). That must have been around 1810. The popularity of Napoleon I is at its peak and the pipe is in demand in the highest circles of society.

Although Meissen was the inventor of this creation it will not stay the only manufacturer. At countless porcelain factories, this figural pipe was imitated, in Germany but possibly also in France. Many such imitations are less attractive than the original Meissen product. The modelling is not as refined and especially the paintwork lacks its sophistication (Fig. 1). A high-quality pipe is a blanc de Chine pipe bowl with very similar modelling. This pipe comes from the porcelain factory in Fürstenberg (Fig. 2). It is interesting to see how the modeller in another factory adapted the details to his own taste and thus came to a very similar, yet different creation. Most striking is the shell motif on the bottom of the bowl, in addition we see that some details are slightly different. For example, the bust is a little more explicit, the decorations more prominent, while a rim around the stub for easy connection to the stem has been added.

Napoleon's portrait pipes remain on sale throughout the first half of the nineteenth century (Note 3). While the target group was initially the politically engaged circle around Napoleon, it will soon decline after his exile. During the Second Empire under Napoleon III, the interest in Napoleon I is alive like never before. Counterfeit portraits from that period are clearly less refined (Fig. 3). The subtlety disappears not only in the porcelain mass, but also in the modelling and the detailing. The painting loses reality and the colours are too bright and unrealistic. Such cheaper copies are in demand with the smoker who adores Napoleon and sees him as an example for a strong personality and powerful statesman with great military merits. It is the product of the smaller porcelain manufacturers who are able to tap into a new market segment with their own creation. The factory in Meissen has now focused on other designs and sets the tone again. Correspondingly with the smokers' circle, the quality of the Napoleon pipes drop back.

About twenty years later, but certainly before 1830, the first clay pipe manufacturers launched a similar portrait of the emperor. Porcelain examples must have served as a source of inspiration, albeit that the manufacturer of clay pipes modifies the design. The porcelain imperial bust is initially majestic and especially the bust itself has been worked out in detail. The specimens from pressed pipe clay, on the other hand, are more schematized. They represent the emperor, but without his imperial dignity. That is why his uniform has been simplified with simple epaulettes and a single star on the breast. This portrait of pipe clay was copied at several factories. The clay bowls were of course intended for a different target group: they were in demand in the lower middle class, while the porcelain pipe at that time was mainly smoked by the bourgeoisie. The Napoleon portraits became very common. For example, we see the same design in three standard sizes labelled grand, moyen and petit. The copies from the factories of Gambier and Fiolet, respectively from Givet and Saint-Omer are almost identical to each other (Note 4). Smaller manufacturers differ somewhat in terms of modelling following the same concept (Note 5).

While the exclusive porcelain portrait pipe of Napoleon I made in Meissen did not find a direct imitation with the makers of clay pipes, some twenty years later we see that the manufacturers of clay pipes do adopt this design. Using a cheaper, smoothly painted porcelain portrait heads, they simplify the design to find a connection with their own customers. What is certain is that the sale of the pipe clay alternatives realized much larger numbers and became more widely known.

Other portrait pipes designed in porcelain factories

As noted, the design of the figural pipe from 1820 takes a great flight at the clay pipe factories. The larger factories attracted modellers who invent and execute original designs. Thus, the figuration of the clay pipe in the nineteenth century became a trendsetter and a great success among smokers. Then something unexpected happens. It is not the makers of clay pipes who are inspired by porcelain, but it is the porcelain factories that seek inspiration from the figurative clay pipe. In this way the porcelain manufacturer tries to achieve an economic advantage simply by copying.

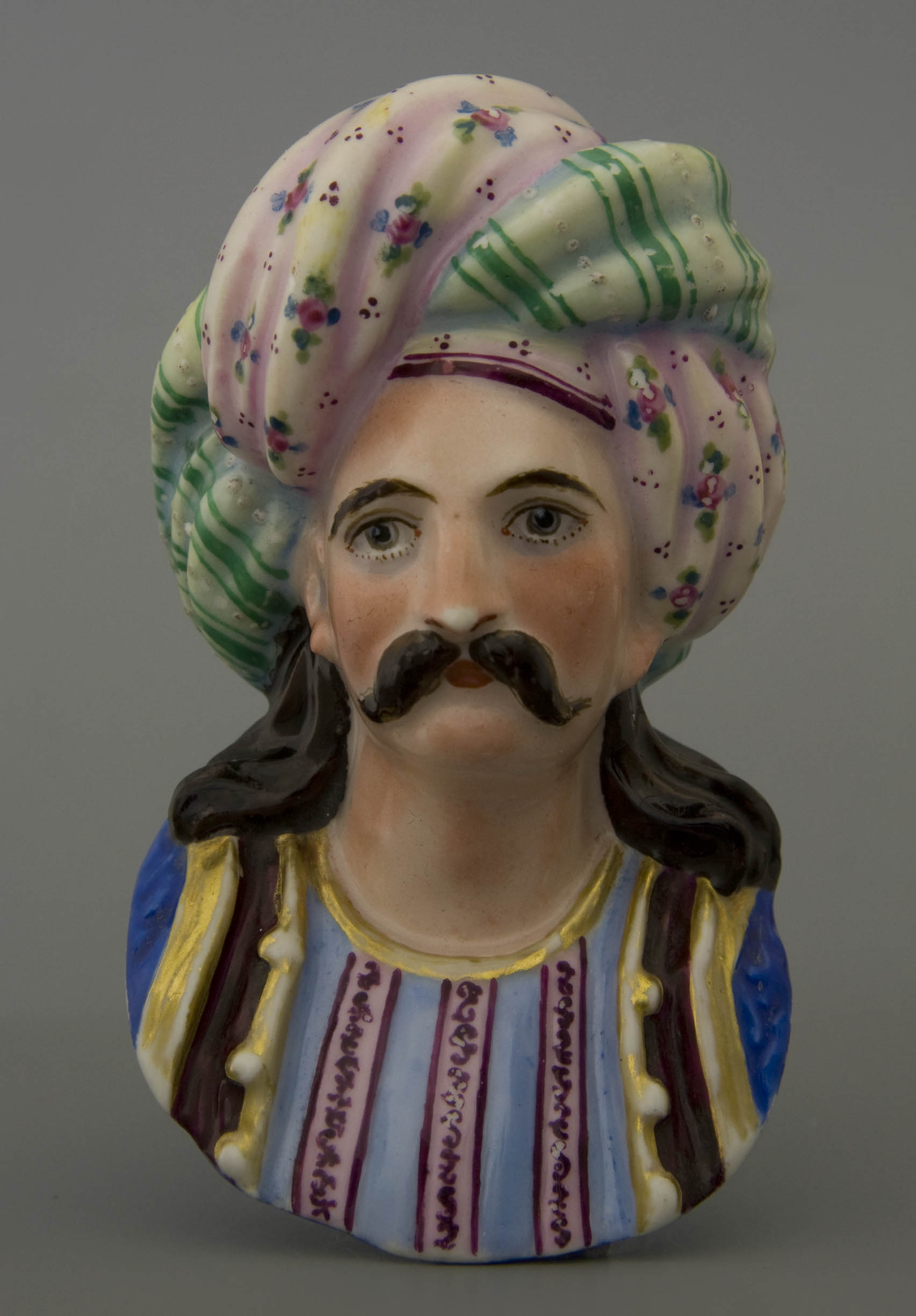

A first example in which the French porcelain pipe is borrowed from the successful figural clay pipe is a majestic portrait of man with moustache and turban (Fig. 4). Since no examples of this design are known in clay, it would suggest that this pipe bowl was designed in the porcelain factory. However, in terms of details in the design, but also in the way the bust is shaped with its short ascending stem and stub, this pipe follows the concept of the figural clay pipe with the characteristics of Fiolet as a starting point. This earliest specimen has been made extremely refined and is closely related to the products from the porcelain factory of Jacob Petit from Fontainebleau. This does not only apply to the refined porcelain mass and appropriate modelling, but also to the use of vivid colours. The fact that the colour palette is fresh and bright provides a sparkling appearance. The glossy glaze skin enhances this beautiful result.

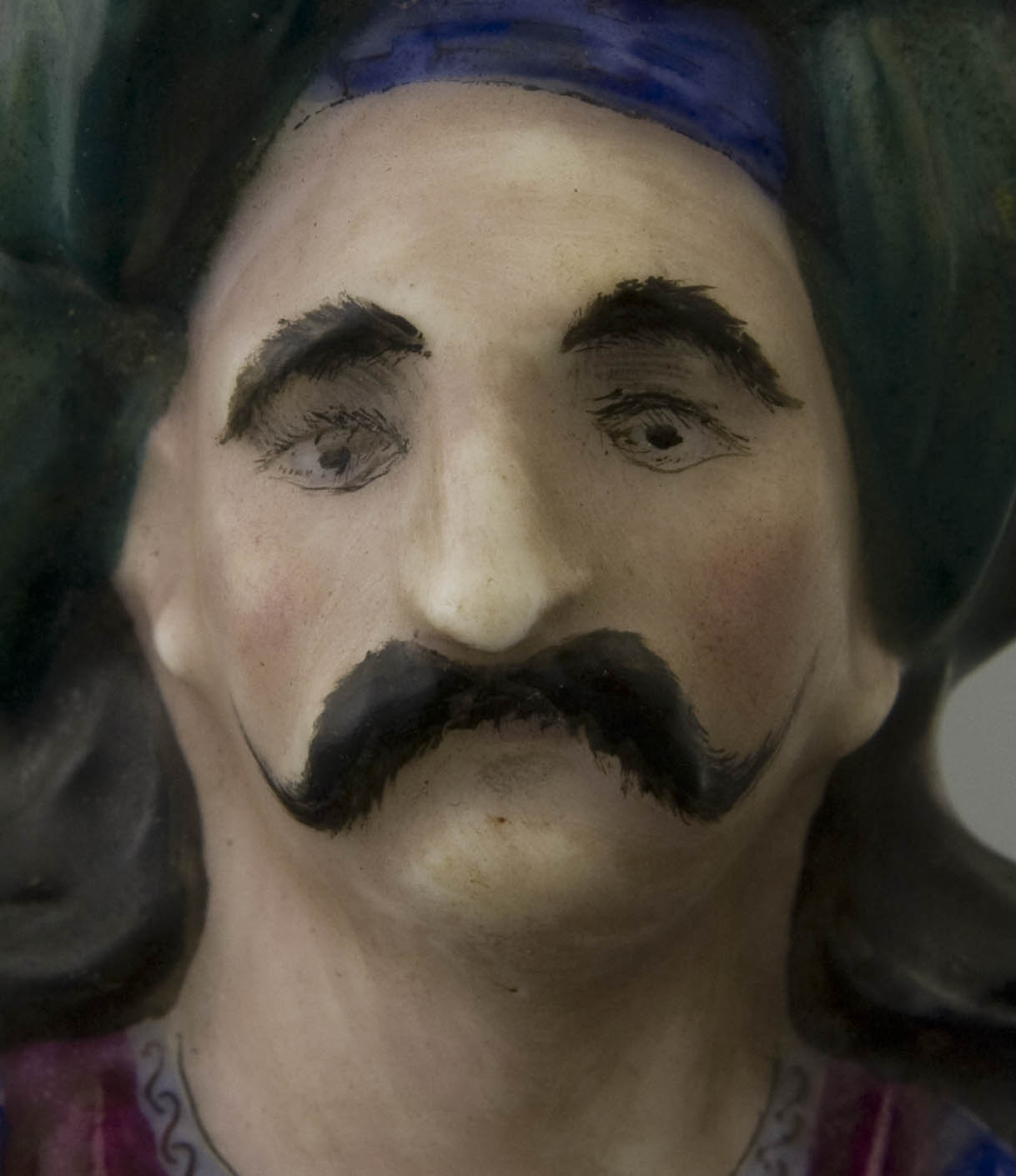

The Turk in turban has been extremely popular which we can conclude from the different versions that have been preserved, partly pointing to production at other factories. An example of the same design is clearly not as delicate (Fig. 5). We see a less powerful shaping, dull glaze and especially a less steady hand in painting. It is unmistakably an imitation from a factory that couldn’t realize the real finesse. The existence of these variants also proves that the porcelain manufacturer often takes his inspiration from the competing porcelain factory, as we already saw in the portrait bust of Napoleon I. You could say that imitating a porcelain pipe from another porcelain factory is a narrower step than basing your design on a pipe from another alternative material. Or course that says something about the courage of the porcelain manufacturer to look about their own horizon.

A second example of a porcelain design with roots in the clay pipe is the portrait of a judge with a skinny face under a tricorne (Fig. 6). It is a tobacco pipe with sturdy shaping that hardly ever occurs in that form with porcelain. Yet with sufficient detail, a distinctive headline has been set down. In this pipe bowl too, both the representation and the proportions are entirely derived from the clay pipe, although the example in clay is missing. The all-over painting is typical for the porcelain manufacture. So, the maker has chosen to cover the white of the porcelain mass with paint. The petit feu of the almost monochrome colours ensures a matte result in muted tones, which resembles in a way a smoked clay. This colour resemblance also indicates inspiration from the other material group. Unfortunately, we cannot identify the production site.

A third pipe bowl made in porcelain that conveys inspiration on the clay pipe shows a caricature woman with glasses (Fig. 7). This is not a large pipe, but a refined object. The pipe bowl represents a so-called tricoteuse, an emotionless woman who, while knitting, observes the victims of the French revolution beheaded. The compact design of this portrait is characteristic for clay pipes and has never been designed like this in porcelain. Yet no clay counterpart is known here either. This means that the original clay pipe is so rare that it is not yet known, or that the design was made at a porcelain manufacturer but based on the style characteristics of the clay pipe. This pipe bowl is also well developed from a technical point of view. For example, the bowl interior is formed separately, so that the smoker was not bothered by hard to reach cavities when packing the pipe, while the hollow space improved the weight of the pipe and, moreover, offered some cooling of the smoke. The finish consists of a meticulous multi-colour painting of muffle colours on the glossy transparent enamel skin. The colouring in particular gives the pipe a striking appearance. Next, the stub is set with gold leaf, but not with a silver fitting as with most porcelain pipes. Unfortunately, it is again not possible to attribute this product to a porcelain factory. In fact, it is not even certain whether we should look for manufacture in France or perhaps in Germany. In that period there were countless porcelain factories active where such products could have been made in principle. The careful painting indicates at least a date in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Clay pipes copied in porcelain

With the portrait pipes in porcelain discussed so far, we see that the design from 1820 is based on the figural clay pipe, although there is no proof of mere copying. The manufacturer was inspired by the clay pipe but came to its own creation. This is different for two pipes, of which an original can be identified in clay giving evidence to be a direct copy. It is a large portrait pipe depicting the bust of the still young Abd-El Kader (Fig. 8), an Arab of Algerian descent who violently opposed the French colonization of his country. The original version in pipe clay was conceived by Louis Fiolet from Saint-Omer. With a height of more than twelve centimetres, it’s size sits between a smoking pipe and a presentation pipe. The only known version in clay has a flat underside so that the pipe bowl can stand stably (Note 6). With Fiolet it happened more often that large pipes were made both with a flat bottom for standing upright and with a round bottom, one for the shop window, the other for the serious pipe smoker.

The dimensions of the clay example and the imitation in porcelain are almost the same. Yet it is not a casting but a completely new modelling, albeit almost identical to the pipe clay specimen. For this pipe, the porcelain maker has opted for a version in Blanc de Chine. This is therefore a glossy glazed product without polychrome, as a result of which this pipe, partly due to the lack of details, has obtained a totally different appearance than its counterparts, both in porcelain and in pipe clay. Because the time of creation is somewhat later than the original by Fiolet, the portrait was updated and given a moustache and fashionable goatee. Another striking feature is the unexpected shallow bowl, which has been left unglazed. This indicates the use as a smoking pipe, because the somewhat rough surface makes it easier to deposit a layer of carbon that ensures better burning of the tobacco and a deeper taste of the smoke. Because of the small bowl, there is a lot of space left in the pipe that promotes cooling of the circulating smoke.

It is remarkable that a second version of the same North African freedom fighter is known, now as unique piece (Fig. 9). The same portrait bust, as noted above, characterized by the narrow conical bust. This creation is again a personal interpretation, now with a naive appearance. There is even doubt as if the maker was a porcelain manufacturer or a dilettante who moulded a pipe bowl for fun. That could be the explanation for primitive design and folk art painting. In any case, the signature on the flat underside of the pipe is interesting. It reads in red letters "FAIT PAR DENIS CLERGET 1866 A SEZANNOI". The year 1866 in the signature ties in with the late days of popularity of Abd-El Kader, the moustache and goatee also indicate a later date. Thanks to the signature on the bottom, we know the name of the maker and we know that this pipe bowl came from one of the as yet unnamed porcelain factories in Sézanne in the Marne district. Despite the large size, it functioned as a normal smoking pipe, as evidenced by the traces of regular smoking on the interior of the bowl.

Both large-size pipes show that clay was the inspiration for porcelain makers, but that copying mainly came from small factories or sometimes even a modest artisan workshop. It is more about conceptual imitations than artistic products . The blanc de Chine version is the most successful because the glaze conceals the imperfections in moulding. With the painted biscuit specimen you can feel the maker's struggle with both the design and the painting. Even the lettering on the bowl base betrays dilettantism. Because of the poor quality of both representations, these pipes ended up with the less prosperous smokers. Those who could spend real money and had good taste would have opted for more artistic smoking equipment in that period.

Three blanc de Chine creations further examined

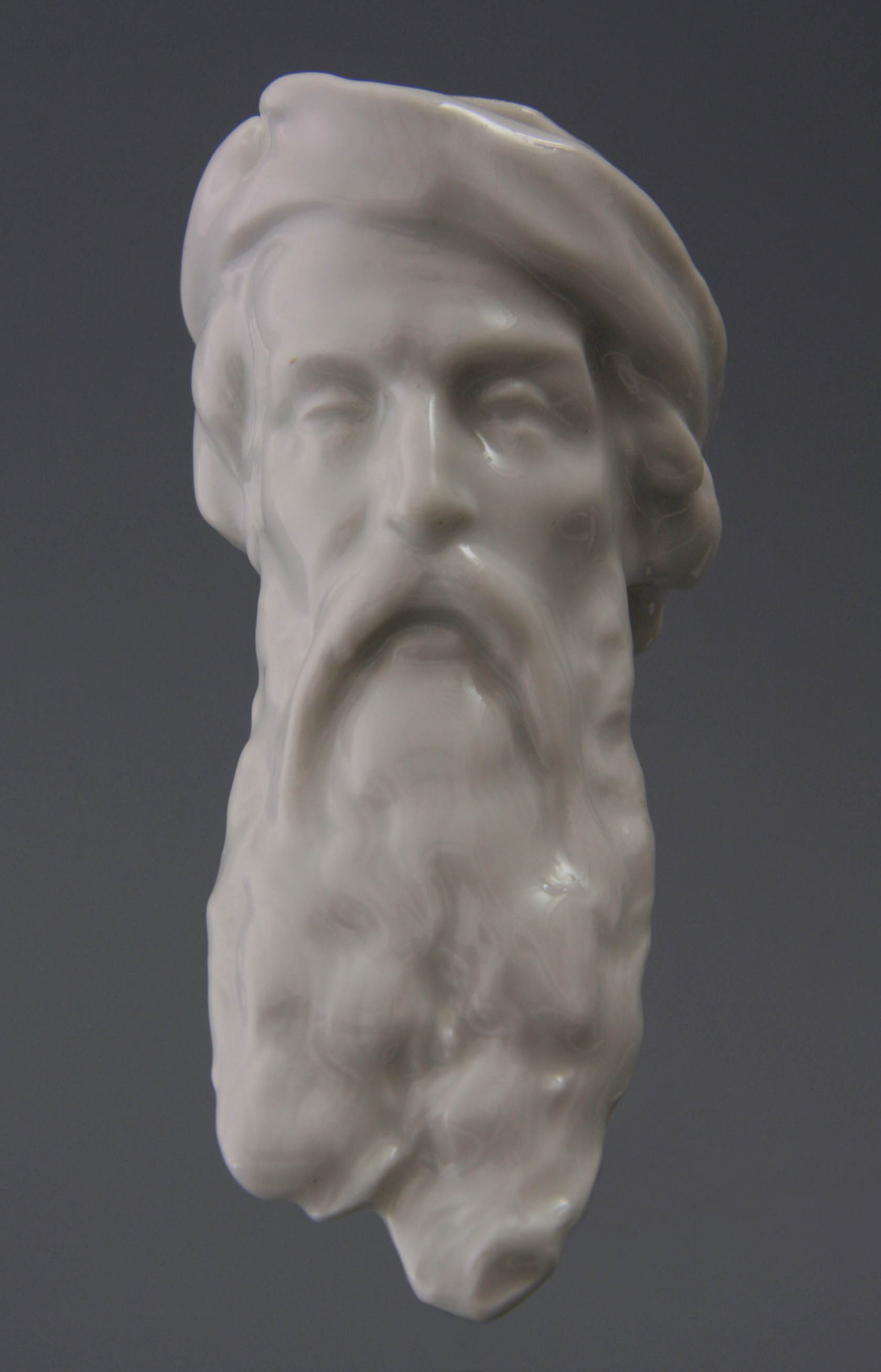

In addition to interpretations, there are pipe designs of indeterminate origin. They are inspired by unknown contemporary products in which the influence of the clay pipe plays a role, but also influences from other materials can occur. Three examples are discussed in this chapter. The first is an attractively designed portrait pipe of a man with a long beard and inconspicuous turban or maybe more a floppy hat (Fig. 10). This bearded head appears to be related to the well-known bearded pipe bowl under the clay pipes, the Jacob pipe, but that is not the case. The Jacob pipe is always solid and rigid in design and bears without exception a text inscription on the turban. Here, there are softer design lines in an atypical modelling. For example, the beard is shaped asymmetrically, something that we rarely see in clay pipes. Probably the inspiration for this pipe bowl does not come from the clay pipe at all but from a carved meerschaum portrait pipe that is always more unconstrained in design or even from a pipe made of wood. Another characteristic also points to this, in particular the way in which the stem is mounted. In this case not with the usual stub or separate metal stem holder, but in a way that has not been shown before. It is clear that this pipe, which always remains immaculate, is a wonderful achievement, although a Sonderstück at the same time.

More in line with the traditional porcelain figural pipes from the eighteenth century is the blanc de Chine portrait of a woman with a grapevine around the head (Fig. 11). This creation seems more French than German and is attributed to the famous Manufacture Royale of Sèvres. However, this pipe bowl shows a close relationship with the clay pipe. This is demonstrated by the simple stem stub, but also the manufacturability in a press mould that consists of two parts. The concept is therefore strongly related to the clay pipe, but the details are more specific to the porcelain manufacturer. For example, what about the braided edge along the bowl opening, that does not occur in any clay pipe.

The third example seems even more closely related to the clay pipe (Fig. 12). It is about the head of a man with crochet nose and frizzy hair wearing a top hat. A rectangular sheet of paper is placed on the left between the hat band on which is an unreadable text. Although this portrait is close to the clay figural pipes, other influences are also visible. The ornament at the bottom of the bowl and the cuff that is not round but hexagonal. This ornament is known for ceramic pipes from Thuringia, while the multi-sided stub points to other Central European pipes made in ceramic. Also of this porcelain pipe no counterpart in another material is known, at least to date. The maker got his inspiration from the prevailing style of his own time, in which the clay pipe was a dominant factor.

Common goods for both industries

In addition to remarkable pipes such as oversized or executed in white, we also find various clay pipes that have been redone in porcelain, as unchanged casts. The copy of the portrait pipe of the poet Anacreon originates from a smaller porcelain factory (Fig. 13). This pipe bowl is a direct replica of a clay pipe in porcelain. In this case, a pipe bowl from the firm of E. Duméril, H. Leurs & Cie from Saint-Omer was reproduced. This is proven, among other things, by the characteristic stub of the French factory from that period, closed with a concentric band that is not rounded off as is usual with the other factories. Greater shrinkage of the porcelain mass resulted in a smaller size, almost too small. For that reason, the bowl is provided with a cylindrical elevation of a few millimetres. With this tobacco pipe the finish is not a glossy porcelain glaze, but a matte petit feu variant. The result is a lifelike portrait pipe, at the base and in the scroll around the head set with gold leaf. However, that colourful and meticulously executed finish did result in a sweet doll's head instead of a serious character. As with many others, the origin of this pipe bowl is unclear. This can be both in Germany, for which the raised bowl opening argues, and in France when we compare the pipe in style and fashion with other porcelain. The date is in the fifties or sixties of the nineteenth century and thus overlaps the production time of the original Anacreon pipe at Duméril.

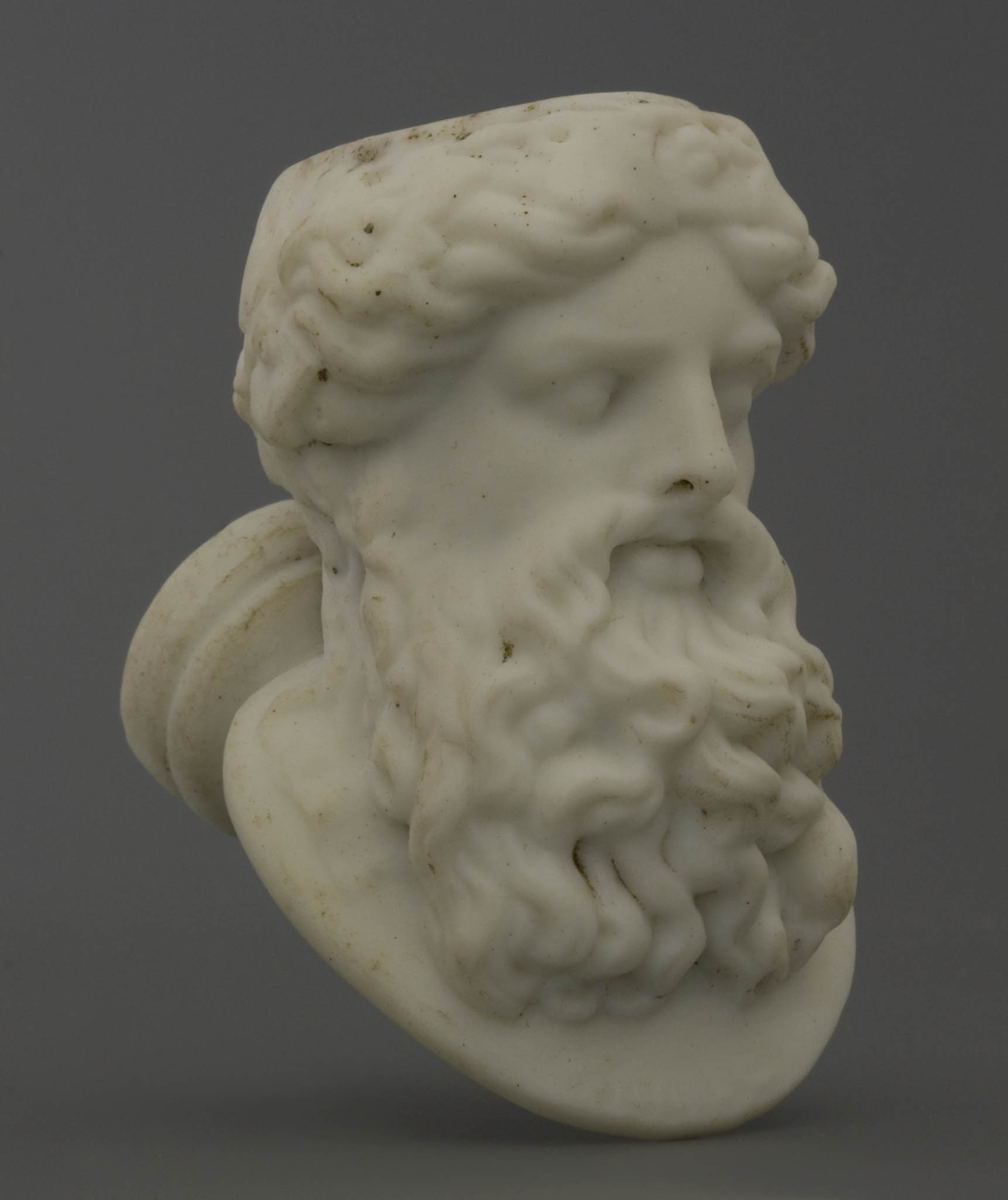

The same portrait pipe of Anacreon came into production a second time, but this time not the small size but the large version, incidentally from the same factory Duméril (Fig. 14, Note 7). For this specimen, a version without paint was chosen and again not glazed, but executed in biscuit. This finish is named parian ware, a matte biscuit porcelain that looks like marble and thus enhances the sculptural effect of the pipe bowl. At this pipe we see again the typical stub from Saint-Omer, closed with a cylindrical band that proves that again a pipe bowl from Duméril was replicated. The shrinkage between the original clay pipe and the porcelain counterpart is again considerable. Not surprisingly, there is always a difference between design and casting, which is even greater with porcelain than with pipe clay. It is the higher baking temperature that gives a stronger amalgamation convenient to handle and therefore suitable for the average smoker.

This tobacco pipe is also made in clay at several factories. The larger version, for example, was in production at Antoine Trees in the river Meuse region, although this version has the usual round stub and can therefore not be used as a reproduction example in the former pipes. In the Belgian Meuse region, the small version of Anacreon was also copied by Henry Cuvellier. The mould for this pipe came to Gouda in 1880 (Note 8). We can notice that the porcelain counterparts are not only made in two different sizes, but apart from that in a range of varieties in terms of look and finish. In that respect, the various porcelain techniques offer more options than pipe clay.

Working in the style of

In addition to direct replicating, another option for the porcelain manufacturer is following the style of the clay pipe . Early examples of this were already discussed, but the phenomenon of imitation continues into the later period. The pipe bowl with the bust of a sailor (Fig. 15) is copied from a clay pipe and shows a stereotype sailor with a simple sailor hat with a flat brim, a design known as le marin. Responsible for the original is the Gambier company from Givet, who supplied this creation before the year 1850 under shape number 560. However, this porcelain pipe bowl has a considerably larger size, of which no counterpart in clay is known. Two possibilities are open. We do not know the original clay version yet, or the porcelain manufacturer has taken the pipe bowl from Gambier as an example and remodelled it in a larger size. That redesigning also yielded some differences in detail, especially in the scarf around the neck, the collars and the size of the anchors on the lapel. The appearance of the porcelain version is not that powerful due to a lack of detailing. Unfortunately, the level of paintwork in particular is lagging far behind. Note, for example, the ridiculously curled moustache opposite a goatee that has the shape of an irregular brown spot. The narrow mouth in red is also proof of how not to paint. Such simple colours imitate the painting enamel of the clay pipe, but are much less successful on porcelain. Because the porcelain mass itself has not been tinted, an inappropriate contrast is created between the hard glaze colours and the white porcelain. From a technical point of view, this pipe bowl is not a bad creation: the pipe is sturdy, fits well in the hand and on the inside the bowl has a regular shape, despite the single-walled nature of this tobacco pipe. The date of the porcelain version overlaps the production period of the clay pipe.

The portrait pipe of a man with fez (Fig. 16) belongs to the same imitation category as the previous pipe. However, it is a design with a long history. This shape was originally designed by Philipp Eugenius Leyhn from Pirna in Saxony. He was a ceramist and focused primarily on the imitation of meerschaum. Initially this pipe bowl was made of siderolith, a material between clay and meerschaum (Note 9). The design became extremely popular, probably because the depicted person is not too specific, but still exudes something exotic. This pipe design is therefore known in various sizes and from different manufacturers. For example, it was copied in the 1850s by French clay pipe factories, including Dutel-Gisclon from Montereau (Note 10), but also in a Belgian company (Note 11). Even a Gouda factory adopted this male head as a cigar holder (Note 12). The porcelain version that is pictured here is on the small side and rather basic. Here too, the painting is actually done in too loud colours with little attention to details, so that the subtlety for which porcelain lends itself so well is missing.

Quite unexpectedly, we can explain the meaning of the unusual painting. The hat with the thin strips of black and red with the porcelain white in between indicates the flag of the North German Federation and later the German Empire, as it was in use from 1867 to 1919. Two crossed American flags decorate the front of the hat. These symbols refer to the group of more than two million Germans, especially from the north-eastern states that emigrated to America in those years. The pipe will be made for this group of poor proletarians as a memory, mascot or even a sign of recognition in their new country. High quality or refinement in the pipe was not a requirement, but a clear symbolic value was. For a porcelain pipe, this pipe is a heavy product, although the inside of the bowl is very usable with a nice, smooth cylindrical bowl wall. Where the pipe bowl passes into the stem, a plug of porcelain is pasted to get the correct diameter of the flue. This prevents tobacco crumb from entering into the stem. The thick porcelain mass and the colours indicate German manufacture, in line with the subject of the painting. The date in the last quarter of the nineteenth century coincides with the wave of emigration, but also corresponds to the crude execution from that period.

Imperial representations

A step beyond imitation with changes is the casting or stated more clearly the replica, the pipe duplicated from a product of another maker. Cast directly from an existing clay pipe, is the portrait pipe known as Impératrice (Fig.17), designed by the J. Gambier company. The Givet factory had two versions of this pipe shape in production, here it is the large size with shape number 844. The launch of that shape was around 1855, at the height of the popularity of Empress Eugénie, the wife of Emperor Napoleon III. Because the original clay pipe was made in a metal mould, it was shaped with sharp details, despite the exceptionally austere design. Little is left of this with this porcelain counterpart. Due to the greater shrinkage of porcelain, the end result is ten percent smaller than the original, with the result that the pipe lost its powerful appearance. Then we see a lack of details because this item is made in a badly worn plaster mould. Finally, the glaze went wrong. The syrupy transparent glaze obscured even more details while the colours were brushed rather cursory. Because these colours are also garishly overdone , the portrayal lacks the intended realism. Eyes, eyebrows and mouth are thin against a pale face, while the red blushes on the cheeks of the empress are not very subtle. A matron like Eugénie will never have been so blushed in her life. This defect is mainly due to the fact that hardly any face colour has been applied, as is the case with many previous pipes.

Beautifully executed is the golden ornament on the underside of the bust of this pipe. This has been carefully applied as a reference to the relief work on the pipe clay example. This gold leaf was not wear-resistant and is generally completely worn away with smoked specimens. In any case, the end result is a not very elegant product with a low value for use because the pipe has no mass for heat absorption. Moreover, the inside of the bowl extends all the way into the neck of the empress and has hidden corners, which means that the pipe is not really comfortable to fill. Although the production site should be located in France in view of the portrayal, a strange detail gives it some doubt. On the edge of the décolleté of the French empress is a German iron cross unobtrusively placed, exactly where the original shows a jewel in rosette shape. That choice will not be coincidental and two explanations are possible. Ironically, the maker put a German symbol on a French export item, and for the attentive French consumer this was of course a huge insult. More likely, however, is that the German porcelain maker used the shape of the French empress to sell as the German Empress Augusta. The bust of Eugénie could well pass for the lovely wife of Emperor Wilhelm I in her younger years, who wore the same kind of gowns as the French Empress, including a similar diadem.

Another imperial representation shown in this majestic porcelain pipe bowl is the Napoleonic eagle in front of the pipe bowl, while the bowl itself represents a defence tower with battlements (Fig. 18). Again it is a direct casting of a clay pipe from the Gambier company in Givet, known under shape number 406 as l'aigle, tête. What makes this pipe so special is that the meticulous detailing of the example has been turned into porcelain quite successfully. So the delicate details were preserved. Because it was impossible to print the fine texts of the battles in porcelain, a solution has been found in applying the names in gold leaf, which has been done in an extremely refined way. With its unexpected yet swirling design and appropriate lettering, this has become an outstanding product. A pity of course that porcelain did not give the unexpected colour nuances that clay did when being smoked. On the other hand, the pipe remained spotlessly white, no matter how long it was used. That is not the case with this specimen, otherwise the gold leaf would have been worn away, because that is not very user-resistant. It is clear that the porcelain factories are inspired by clay designs and do not hesitate to adopt them without any change. These two pipe bowls prove that the quality can be excellent as well as kitschy. Again this section is about two examples from lesser factories, the first not really successful because of the colour scheme, but the second one is well-done. Unfortunately, there are no traces of a mark, so we will probably never know which companies produced them.

Less prestigious designs

Finally, another three examples of more simple, but very successful porcelain pipes. They show that even the simple clay pipe becomes the subject of imitation. The first is a stub stemmed pipe bowl with a goat head at the base (Fig. 19). Again this product is an outright casting of a pipe from the popular Gambier company. On the stem we can even see the shadow of the original inscription "GAMBIER A PARIS". Apparently the manufacturer did not care about the pipe being copied from another maker or he even speculated on better sales by Gambier's good name. Although this is a modest decoration with some subtle colour accents, the result is quite successful. The choice of pink and grey as softer colours also contributes to a harmonious result. The heavy modelling and the negative smoke quality of porcelain will of course remain, as a result of which the pipe was not considered particularly suitable for the picky consumer.

A similar example shows a stub stemmed pipe with four rats around the bowl, the tails tied together at the heel (Fig. 20). Here, too, it appears to be a casting of a Gambier pipe, namely shape 900 (Note 13). However, this pipe has been completely redesigned by the porcelain maker. For example, the rats in the porcelain version are placed higher on the bowl and the knotted tails are no longer connected to the animals either. It seems that the modeller had not understood that playful detail. Furthermore, a lid rim is provided with brass hinged lid, a common practice with porcelain. We do not find mark stamps of Gambier in this pipe bowl, consistent with the fact that the pipe has been remodelled. However, the porcelain of this pipe is more refined than at the goat head, while even an inner bowl is provided which leaves a cooling space and also a moisture reservoir on the underside of the bowl. The painting is also done in more detail with four colours plus a few gold accents between the twigs as a luxurious finish. Moreover, the white of the porcelain plays a part again and ensures a fresh look of the pipe bowl. Probably it is pure coincidence that both the pipe bowl with the rats and the one with the goat head is depicted in an advertisement of Gambier from the year 1854 (Note 14). Because of the better making of this pipe bowl, but also the somewhat later date, we have to conclude that the production place of both porcelain pipes has certainly not been the same.

Less striking and, strictly speaking, no longer figurative is the last pipe in this article. It is a porcelain tobacco pipe showing a bird's claw,replicated from a Gambier clay pipe (Fig. 21). The shape is registered under number 1464 and was designed in the year 1885 (Note 15). Despite the glaze skin that always slightly obscures the shape, this pipe is just as fine in modelling as the clay counterpart. This is especially visible in the openwork bird toe at the bottom of the pipe bowl. While the Gambier version was often finished with dotted enamel, the porcelain version shows a more exclusive glaze painting. The unadorned part of the pipe bowl is covered with a stylish turquoise on which an ornamental painting has been applied heightened with gold. The full clay stem of the example cannot be made in porcelain of course, so a mounting was required. It was found in an engraved silver band and a steady curved mouthpiece made of real amber. This pipe is the most recent example of the interaction between clay and porcelain. In the twentieth century the wooden pipe dominates and the pipes of clay and porcelain disappear gradually.

Looking back at the nineteenth century products

The porcelain tobacco pipes highlighted here are illustrative of the interaction between two types of ceramic workshops. They are elucidative for balance between the clay pipe and that of porcelain, determined by mutual imitation and desire to copy.

The most attractive products such as the Napoleon portrait bust (Fig. 1) and the bust of a Turk (Fig. 4) are intended for the richest smokers. Gradually the design generalizes and specimen of a lower level emerge. The judge (Fig. 6) or the ‘tricoteuse’ (knitting lady) (Fig. 7) lack the true fineness but are certainly intended for the smoker with the developed taste. With the coarsely painted figural pipes (Fig. 15-17), the quality has fallen so sharply that they are only bought by customers with little taste, or smokers in the lower middle class who want to show themselves with something semi-chic. Because the audience lacked a developed sense of taste, they were charmed by this figurative kitsch. On top of that, a major reason for purchase was of course that the price was within their reach.

In addition to the quality of the product, we can look at the origin of the inspiration. This runs from personal designs (Fig. 4-6, 10-12) through inspiration and imitation of the genre of the competitor (Fig. 1-3, 7-9, 15, 16) to outright reproductions and copies (Fig. 13, 14, 17-21). The large factories in both branches operate on their own and generally follow the fantasies of their designers, although the spirit of the times naturally provides similar characteristics. These initiatives are lacking in the smaller workshops, where there is more imitation and copying. The lack of artistic ability is the reason why small porcelain factories mimic designs of pipes of any material in porcelain. It is logical that they borrow their creations first of all from the clay pipe, since the clay pipe was extremely popular and widely available in the nineteenth century.

With the nineteenth-century porcelain figural pipe, the painting is a tricky issue. Polychrome painting of pipes is a profession that requires great skill and very subtle work. The better nineteenth-century porcelain factories understood this art as it had become a tradition since the eighteenth century. This is also proven with the stummels with extremely finely hand crafted paintings in miniature. In many figural pipes, however, a good result was not achieved, due to both the technology and the colour painting. In later times, working under time pressure with a rough brush and in screaming colours could not lead to an attractive product. Colour accents such as eyebrows or a moustache become weird lines in a white field, without any sense of naturalism. In that respect, the clay pipes with their sharp relief, muted colours and limited enamel accents are much more subtle than these painted porcelain dolls' heads.

Where clay pipes gradually colour during use in ever-changing shades of brown tones, this is not the case with porcelain. That material is impenetrable and therefore does not change colour. Blurring of screaming colours will never occur, at most a bit of wear. The problem of lifelike painting is the reason that a relatively large number of porcelain portrait pipes came onto the market in white, as Blanc de Chine. In fact it is precisely in this version that they are preferred because of their perpetual spotless white colour.

It is certain that every creation had a logical sales price, with Jacob Petit's work at the highest price and the smoothly painted imitation bowls available for a lower amount. An object for every purse. For example, a simple Zouave portrait (Fig. 16) became a suitable gift for a emigrant, while Empress Eugénie (Fig. 17) would be purchased by a German smoker who recognized the lovely spouse of his German emperor. The more than twenty pipes in this article found customers between the spoiled elitist smoker and the common man who wanted something special. The willingness to spend determined in which circle the pipe would be smoked.

It is not easy to get a picture of the smokers who coveted these nineteenth-century porcelain pipes. With the eighteenth-century copies, it is a highly exclusive product with an exceptionally artistic value and correspondingly high purchase price. The elite were the only buyer, together with a rare very well-off smoker. Such porcelain pipes could be a popular gift item, even desirable for the non-smoker. In the nineteenth century that pattern broadened. The production of porcelain is taking off enormously, so the article is geared to a wider target group. In addition to the general appearance expressed in design and quality of the product, there is the significance of the represented person aimed at a specific target group. The variety in porcelain pipes is also growing. It is no longer a rare phenomenon, but rather a standard available item.

As we have seen, the interaction between the porcelain figural pipe and the clay pipe as discussed in this article changes over the course of half a century from a positive inspiration to an almost marginal product group. Within one generation luxury creations lapse to kitschy gadgets without quality. These are curiosities that only surprise us for their similarity with the much better-known clay pipe. However, these types of porcelain pipes are disappointing due to their unarticulated modelling and careless painting. It is not surprising that the real porcelain devotee nowadays ignores the simple porcelain tobacco pipes. Needless to say that the fact that these tobacco pipes cannot be attributed to factories makes them less desirable. Despite everything, they are nevertheless a special group in the history of the tobacco pipe worth looking at.

© Don Duco, Amsterdam Pipe Museum, Amsterdam – the Netherlands, 2017.

Illustrations

-

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of emperor Napoleon I. Meissen, Königlichen Sächsischen Porzellan-Manufaktur, 1810-1840.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 15.103 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of emperor Napoleon I. Fürstenberg, Fürstenberg Porzellan Manufaktur, 1820-1850.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.567 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of emperor Napoleon I. Bohemia, 1830-1870.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.900 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of a Turk with turban. Fontainebleau, Jacob Petit ?, 1825-1850.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 15.096 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of a Turk with turban. Germany, 1840-1860.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 15.602 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of a judge with three-sided stitch, a snake on the bottom. Germany, 1840-1880.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.158 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of a tricoteuse (knitting lady) with glasses. Paris, 1820-1840.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 15.101 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of Abd-El Kader in blanc de Chine. France, 1835-1855.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.566 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with the bust of Abd-El Kader in biscuit with polychromy. France, Sézanne, Denis Clerget, 1866.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 14.283 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with head of a man with long beard and turban. France, 1830-1870.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.293 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with head of a woman with vine. Sèvres, Manufacture Royale, 1810-1840.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 15.089 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with head of a man with hook nose and hat. Germany, 1850-1880.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 11.395 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with head of Anacreon, small size in polychrome and gold. Germany ?, 1850-1875.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 11.439 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with head of Anacreon, large size in parian ware. Germany ?, 1855-1875.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.410 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with bust of a sailor with simple flat-brimmed hat. Germany, Bohemia, 1855-1880.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.033 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with head of man with fez. Germany, Bohemia, 1870-1890.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.998 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with bust of empress Eugénie. Germany, 1855-1865.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.486 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with bowl a sitting eagle in front of a defence tower, inscriptions in gold leaf. France, 1840-1870.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.893 -

Tobacco pipe made of porcelain with a goat head at the base of the bowl. France ?, 1855-1870.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 8.543 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with four rats around the bowl, semi tails as a heel. France, 1870-1885.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.561 -

Tobacco pipe of porcelain with egg-shaped bowl held by a bird's claw with four toes. France, 1885-1900.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.048

Notes

-

Walter Morgenroth, Tabakpfeifen Sammeln, Kunstwerke in Porzellan, München, 1989.

-

Helmut Scherf, Thüringer Porzellan unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung der Erzeugnisse des 18. und fruhen 19. Jahrhunderts, Leipzig, 1985, No. 168.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.813 (smaller miniature coloured) APM 19.416 (coloured with changed moulding).

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 8.827 and APM 16.510. Don Duco, Century of Change, the European clay pipe, its final flourish and ultimate fall, Amsterdam, 2004, p. 37, Fig. 74, shape 11.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 14.530 Dutel-Gisclon.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 1.092.

-

Duco, (Century of Change), 2004, p. 57, Fig. 120 (without shape number).

-

D.H. Duco, Firma P. Goedewaagen & Zoon, Fabrikantencatalogus uit 1906, voorzien van historische inleiding en verklarend naamregister, Amsterdam, 2000, p 19. Duco, (Century of Change), 2004, p. 103, Fig. 217.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 7.885 and APM 18.839.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 13.746.

-

Duco, (Century of Change), 2004, p. 42, Fig. 84, shape 130. Catalogue Wingender-Knoedgen from Chokier.

-

D.H. Duco, De Nederlandse kleipijp, handboek voor dateren en determineren, Leiden, 1987, p. 129, Fig. 664. APM 1.205.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 6.605.

-

Jean-Léo, Les pipes en terre françaises, du 17me siècle à nos jours, Bruxelles, 1971, p. 15.

-

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 8.157.