The dating of pipe finds across Europe, a preliminaryguideline

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Het determineren van pijpvondsten verspreid over Europa,

een richtlijn

Publication Year:

1999

Publisher:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description:

Method for determining pipe finds by analyzing the model and, starting from the Gouda pipe, to determine in four steps where a clay pipe can be made.

Introduction

The discovery of a clay pipe can be of great use for historical archaeology. A pipe is often highly datable and it can also supply additional information about the past. The quality of a pipe can for example indicate the social class of the owner, also giving some idea about the taste of the smoker. The way a pipe is finished tells us about the manufacturing techniques in common use, and the skill of a particular maker. Above all, the find of clay pipes gives us an idea of the varieties in use, and the quantity produced including trade patterns at a particular point in time.

Unfortunately the archaeologist only makes limited use of clay pipes. There are two reasons for this. Firstly there is a lack of adequate knowledge, a global problem caused by a lack of useful publications on the subject, and the circular problem whereby mistakes are perpetuated from one publication to another. This in turn causes errors in interpretation. Secondly there is the human factor, skills of the researcher needing to be built up by experience. Subtle differences in the details of the clay pipe might be missed and often produce the wrong identification.

The purpose of this article is to produce a method to identify clay pipes from the European countries where there is still little archaeological information available. My starting point is the existence of a strong influence in bowl-shapes and bowl-styles which continually influenced the various West European centres. Of these types many of the local ones are still undiscovered. One fact however is, that the clay pipe developed in Gouda influenced clay pipes in many other regions. Therefore, if the Gouda bowl type is known, this can then be the starting point when examining a pipe, in this way the identification comes in the right track.

It is not just boasting to single out the Gouda pipe as the starting point to date and identify European pipes. There are other reasons. Gouda is the predominant pipe producing area of the Netherlands. In this city there has been a strict guild structure since 1660 and so the industry was regulated, the production of pipes quickly becoming standardized, despite being composed of hundreds of small workshops. The influence of the Gouda pipe on the Dutch pipe industry is evident from 1630. On the top of this, Gouda pipe makers started to export so spreading the influence of the Gouda pipe worldwide. Above all others, the Gouda pipe was admired for its fine clay, elegant shape and delicate finish. This particular pipe therefore became the subject of worldwide imitation and inspiration. The history of Gouda is well established having been studied as well from historical as from archaeological point of view.

The second important influence on pipe styles came from England. However there is a good reason why this is secondary. In England pipe making has always been a small-scale cottage industry with many different regional types. There are a great variety of shapes and styles whilst on the whole the quality is poor. These local differences make the clay pipe easier to identify, which is advantageous to the English archaeologist, but the lack of a national style means it has less influence. In addition, the product was not so fashionable to copy. Hence it has incidental rather than lasting influence in other regions. Above all, we see influences from adjacent regions. In a future article more attention will be paid to the English clay pipe, but for the purposes of this paper only marginal examples are used.

The four step system

In order to identify European pipes, we need to decide which questions to ask, and in what order to ask them. A system is developed which divides the influence on shape into logical groups. Each group has a uniform shape representing Gouda or other production areas. The four groups are:

- the original Gouda style

- the Gouda imitation

- the local style

- influences from other centres

In this article main attention is paid to step 1, simply because this step is the basis of the system. Gouda is the starting point of the system to identify the European clay pipe. The next three steps are only dealt with representative examples. Our knowledge of the European pipe is still limited and a comprehensive survey is not yet possible. If our knowledge of groups 2 to 4 was as thorough as that of group 1, it would be time to publish the European handbook of clay pipes.

Although this article focuses mainly on the development of the shape of the clay pipe, a similar article could be written on the decoration. However, since the majority of clay pipes are plain, the decorated pipe is not included. Also it is necessary to limit the period to the early period up to about 1800. The nineteenth century clay pipe is less important to archaeologists as a dating tool.

Step 1: the original Gouda style

The leading question here is: does the pipe fit into the Gouda typology. To decide this we need to know the evolution of the Gouda clay pipe. The development of the typical Gouda pipe-shape starts about 1625 and shows three basic types that form a strict chronology. These basic types are introduced in my 1987 handbook (note 1). They were developed under the influence of the Dutch smoker. The clay pipe achieves a balance between the growing consumption of tobacco, the perfecting of manufacturing techniques and a strive to excel its beauty.

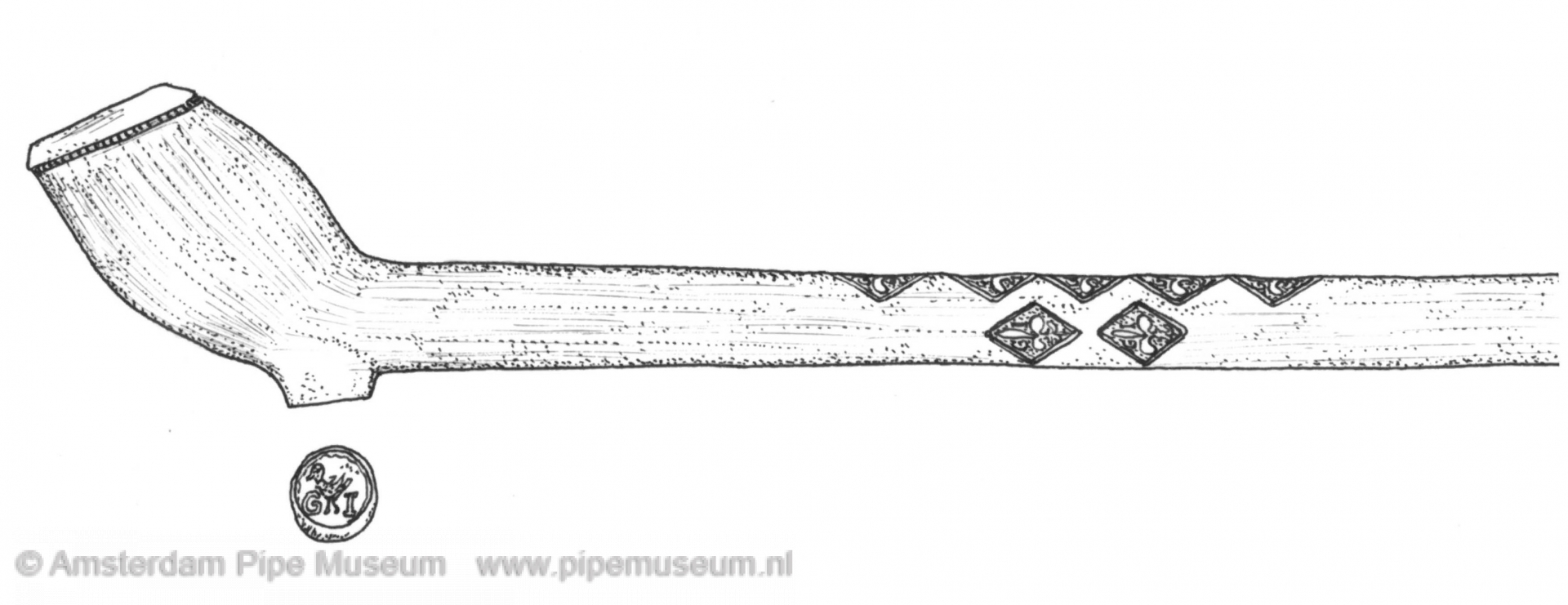

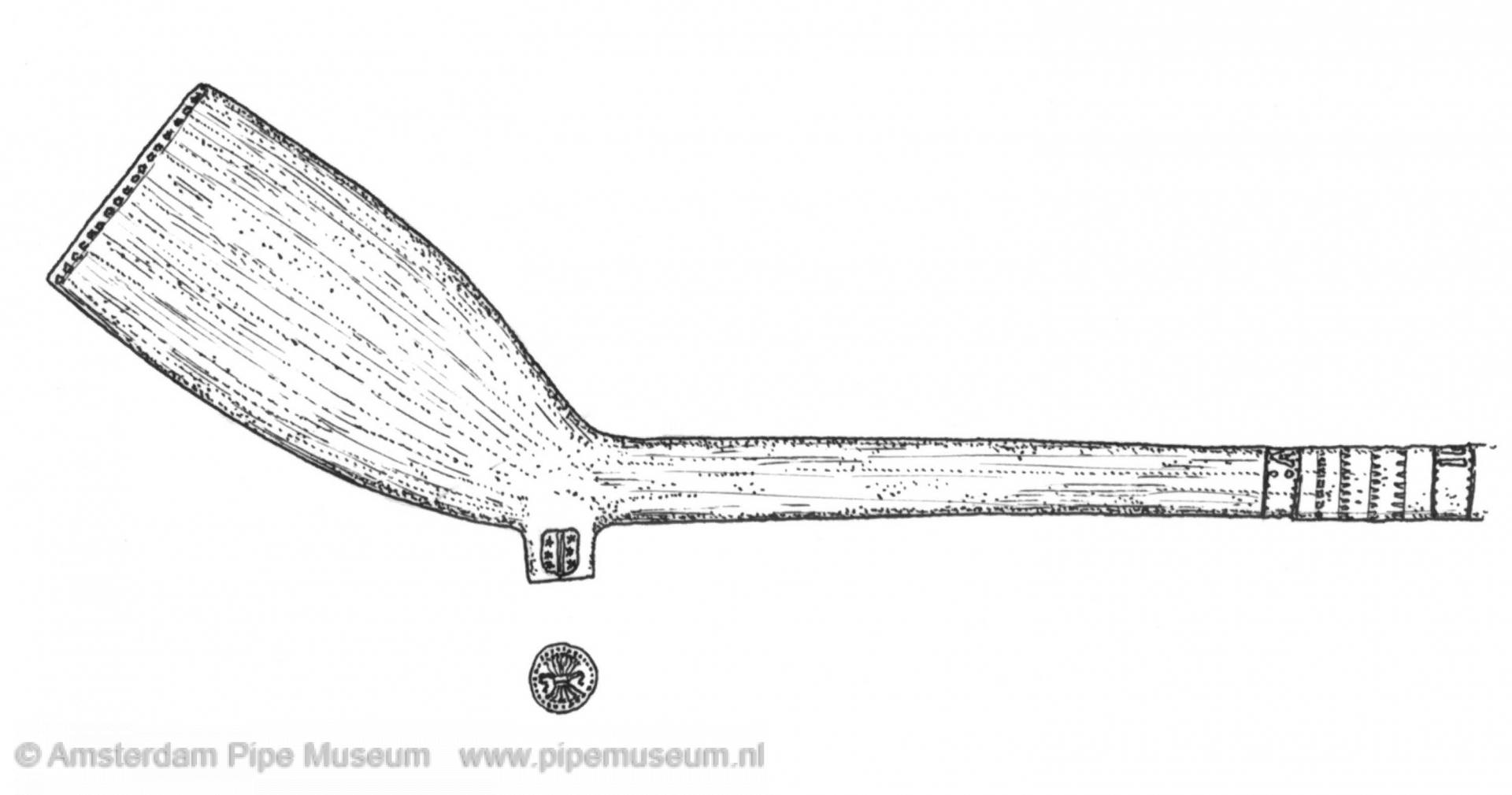

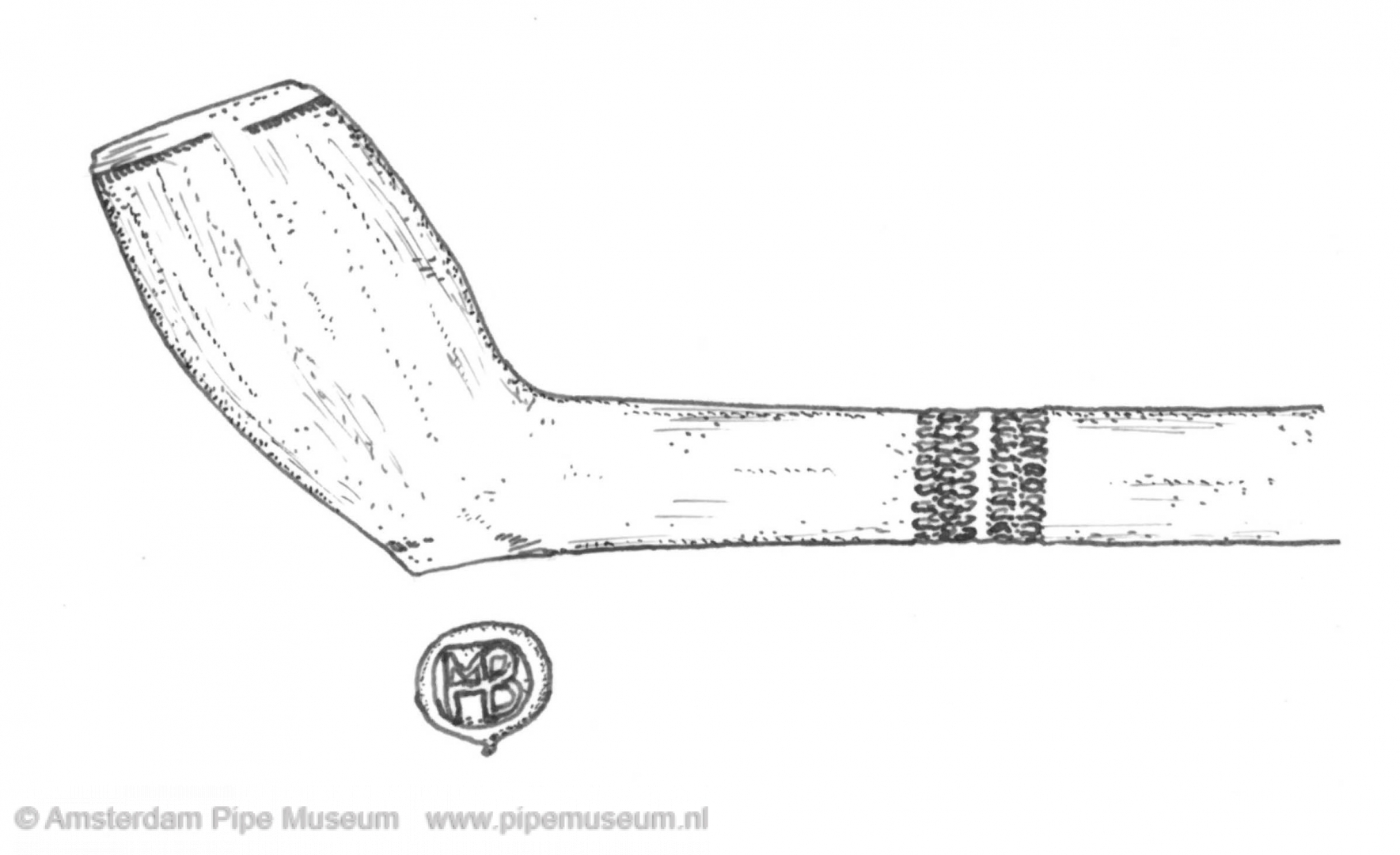

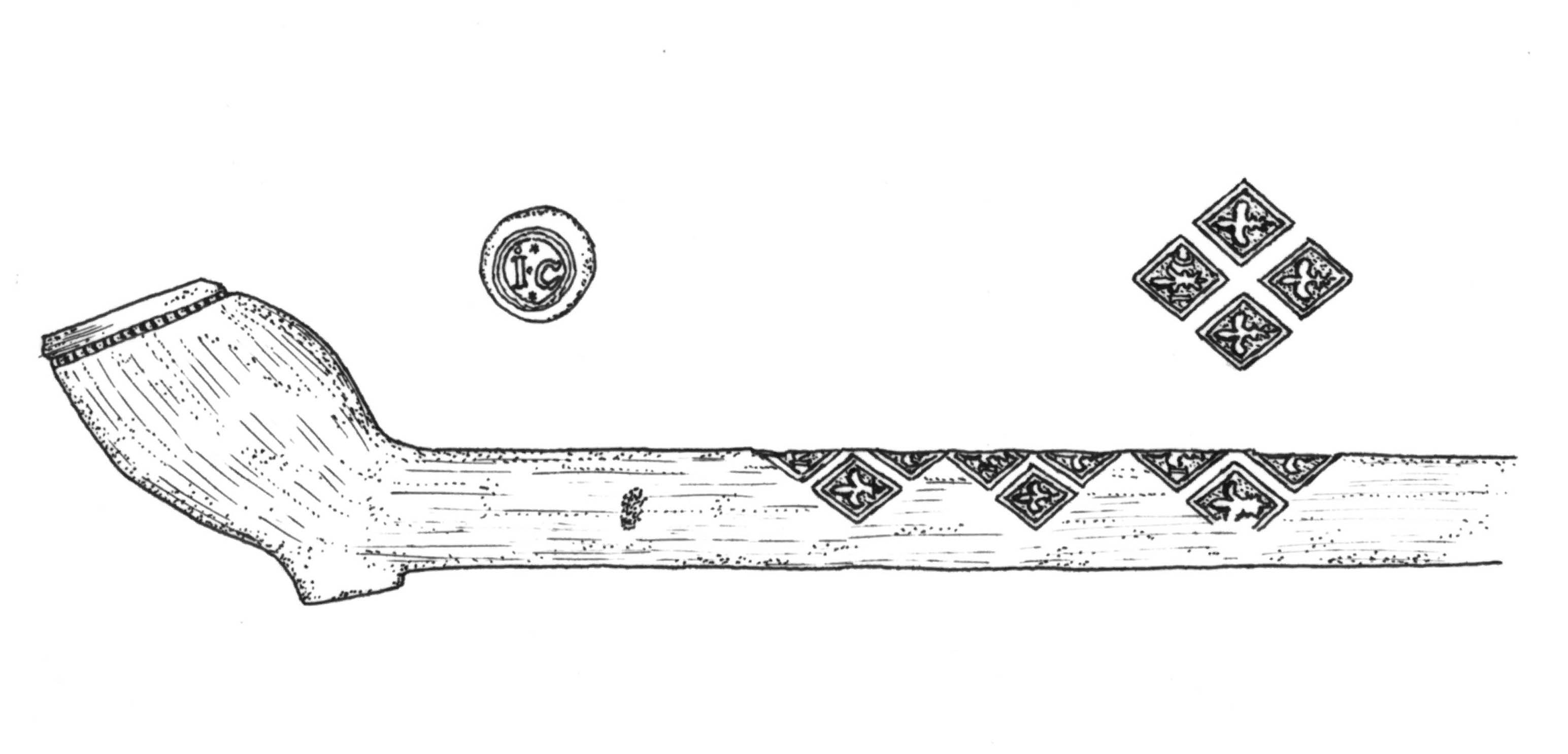

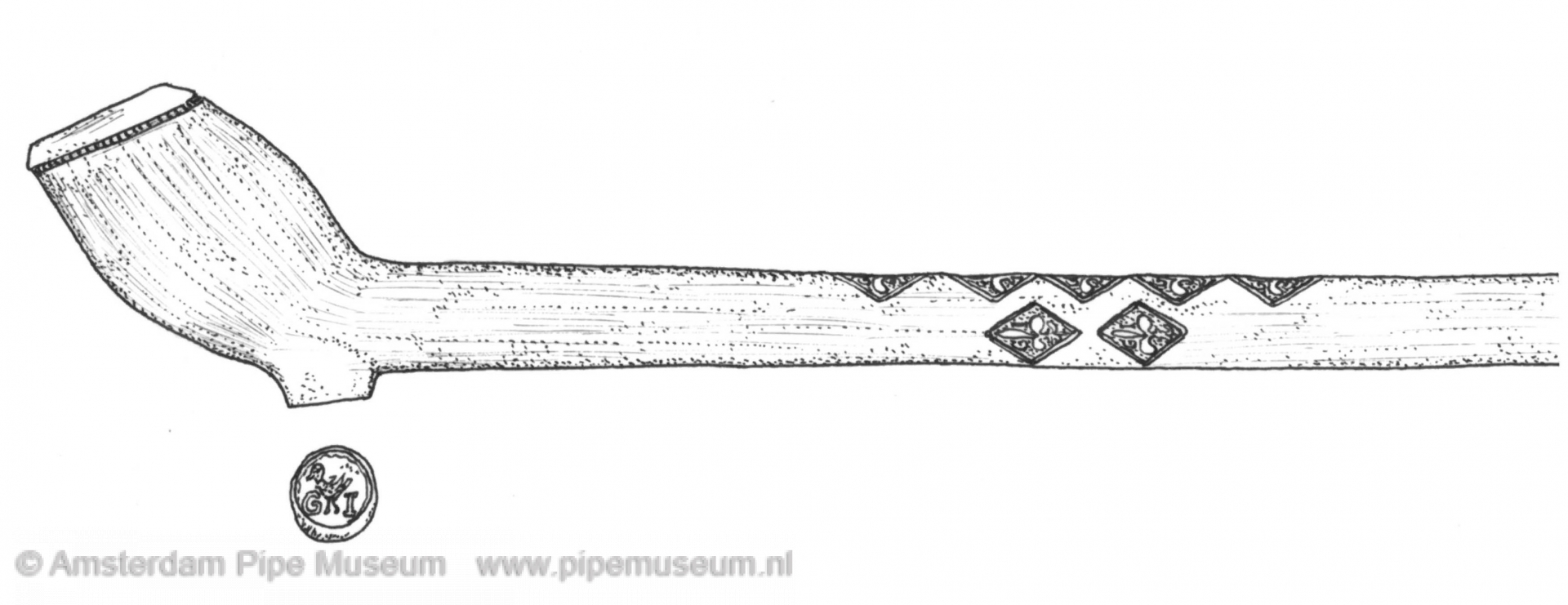

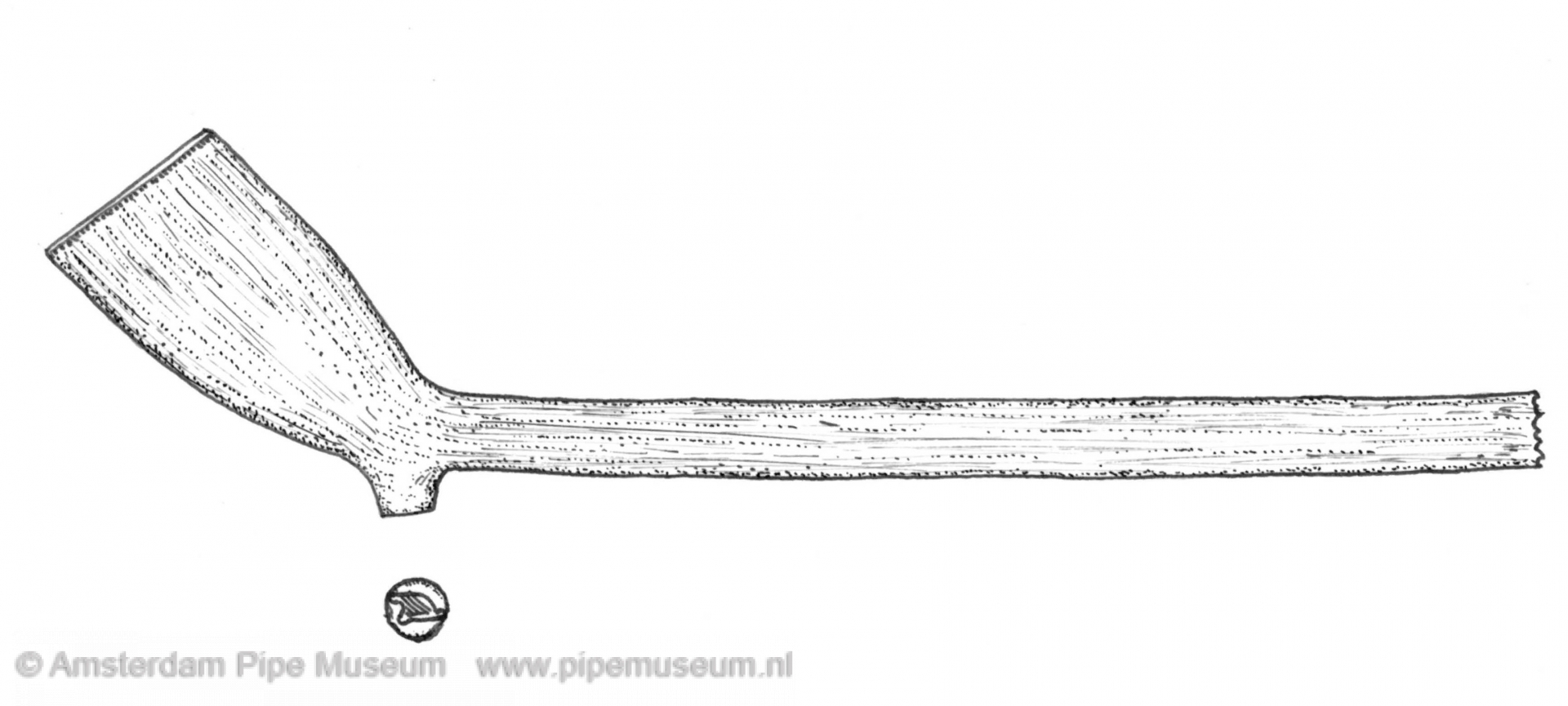

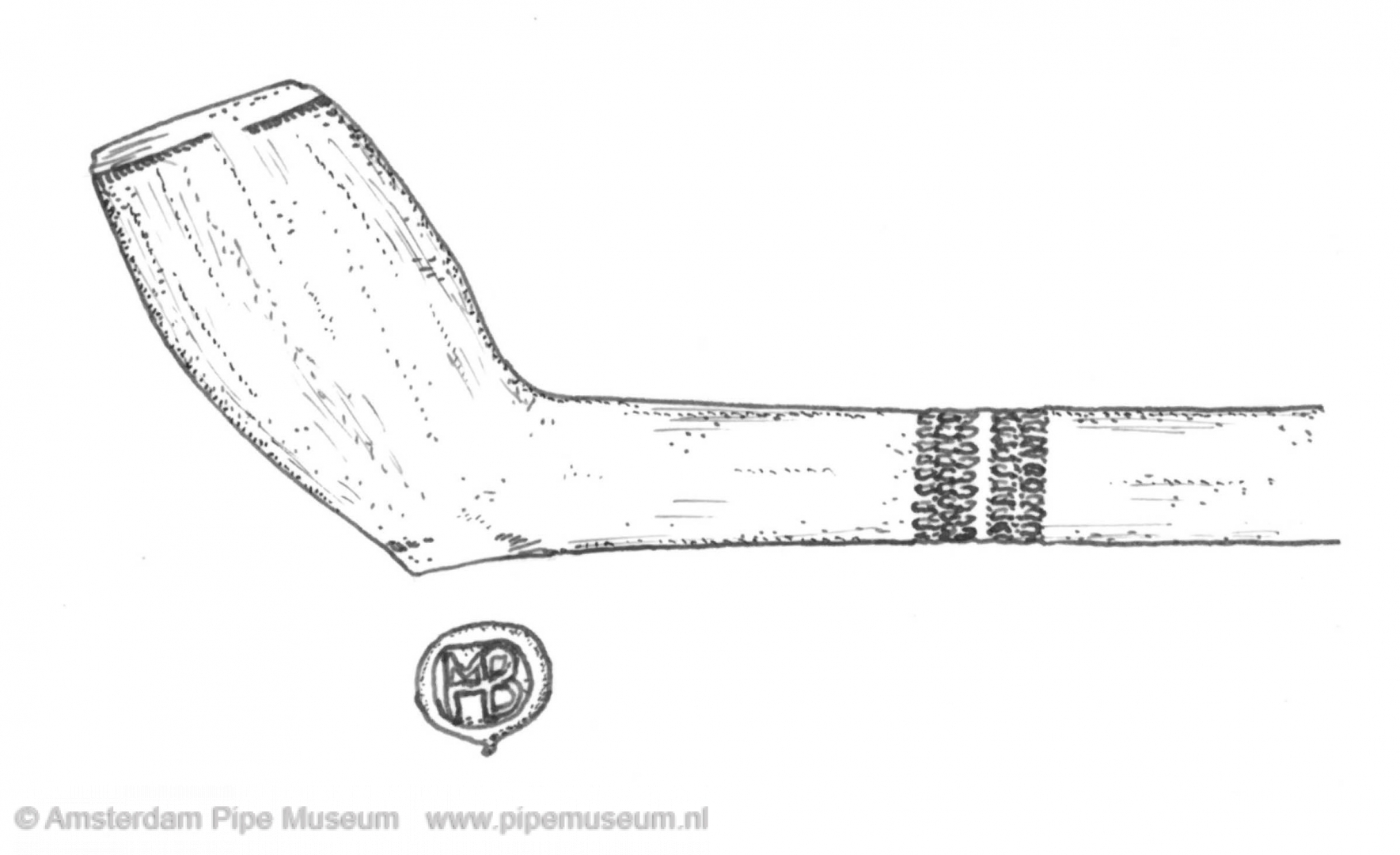

After a period of instability in the shape between 1580 and 1620, about 1620 the type stabilizes. Basic type 1 (Figs. 1-3) emerges from various pipe shapes, and between 1615 and 1625 this shape is generally accepted as the most suitable and most beautiful and it is adopted by most makers in Holland (Fig. 1). From the beginning the shape shows a bi-conical bowl-line, a round heel having a small step where it changes into the stem. The size of bowl is generally related to the length of stem. As well the average size, smaller and larger examples are also found. Therefore dating based on the size of the pipe give misleading results.

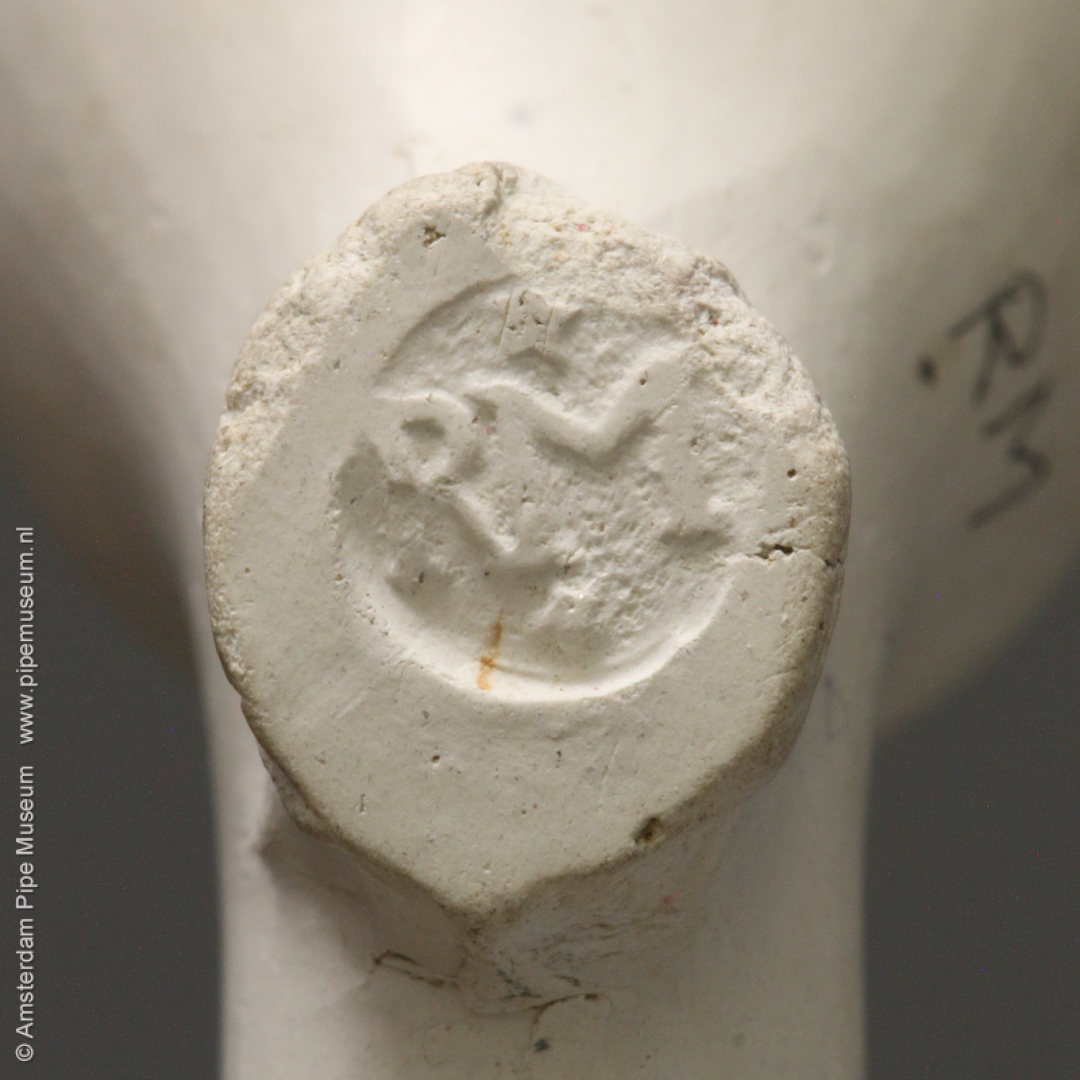

In the finish of the clay pipe two different qualities can be distinguished which we indicate in Dutch as "grove" (literally rough, coarse) and "fijne" pipes (literally fine). In general the coarse pipe is less delicate in shape and certainly in its finish. The milling around the bowl rim is only applied on the stem side. The pipe is unmarked and was never polished with agate or smoothed in any other way.

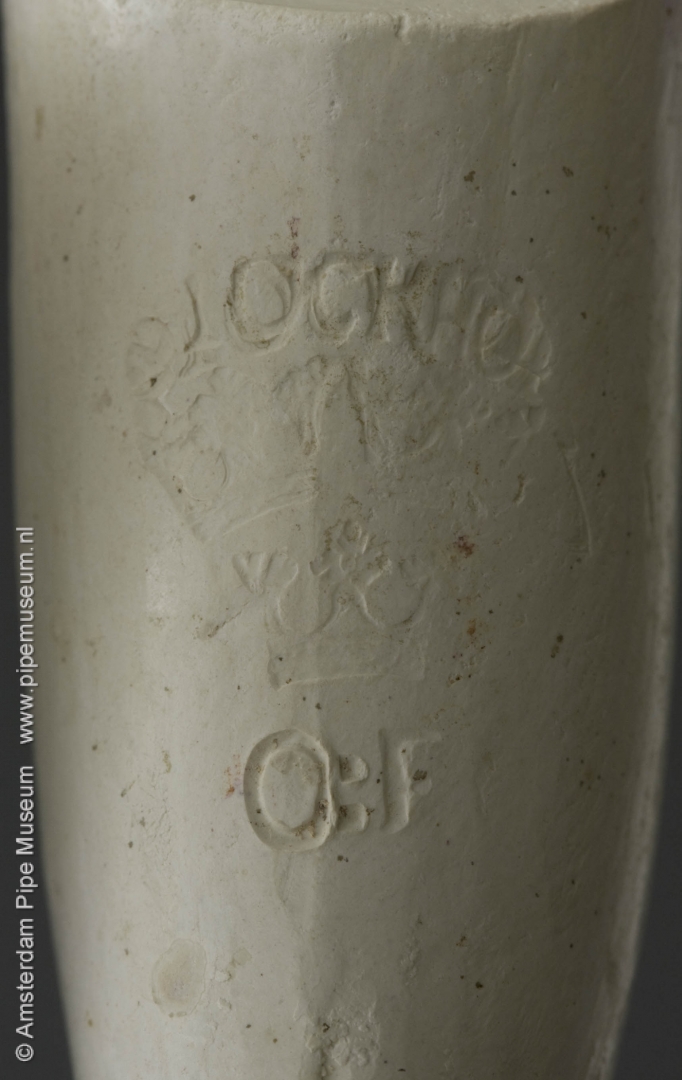

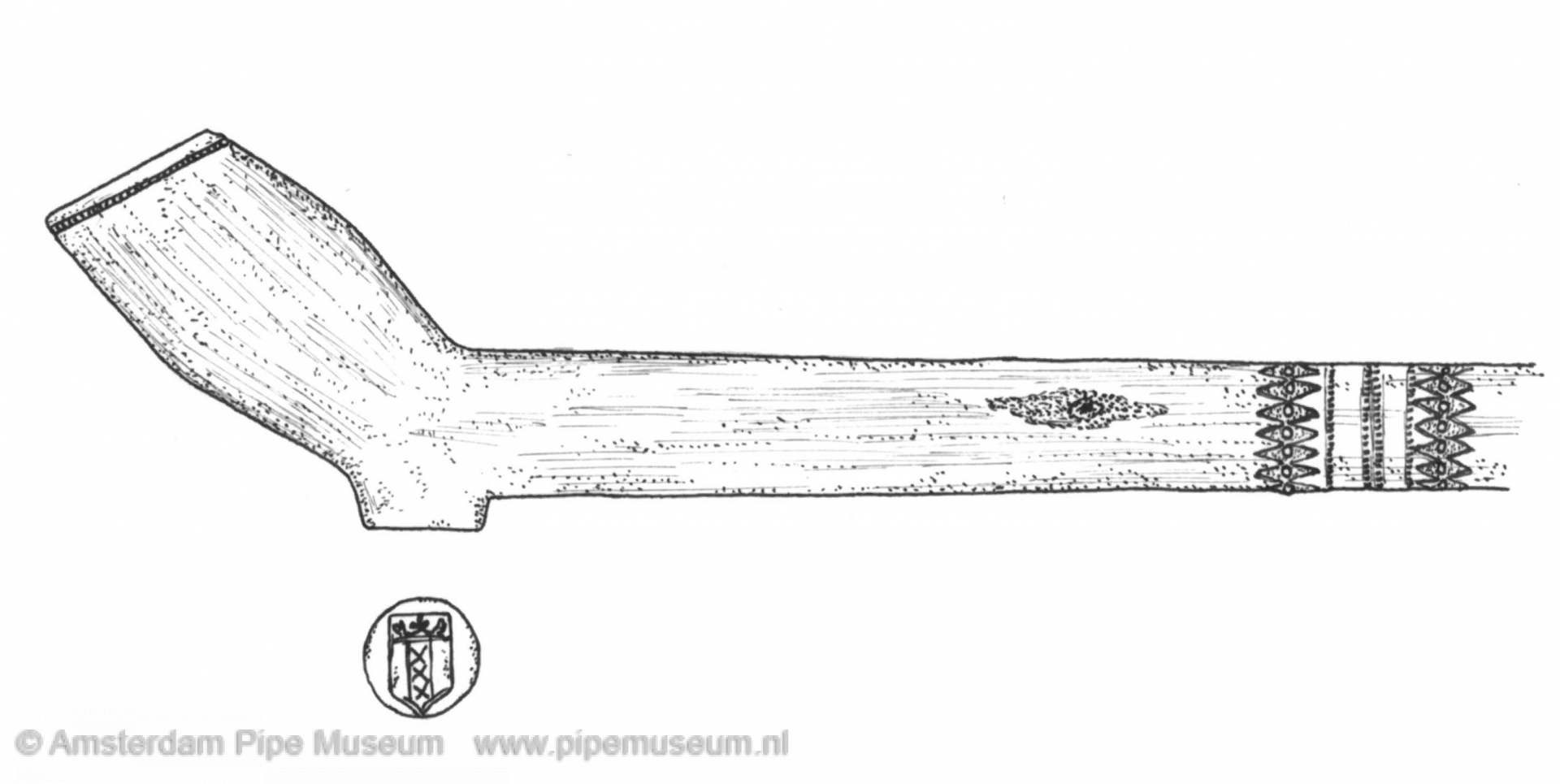

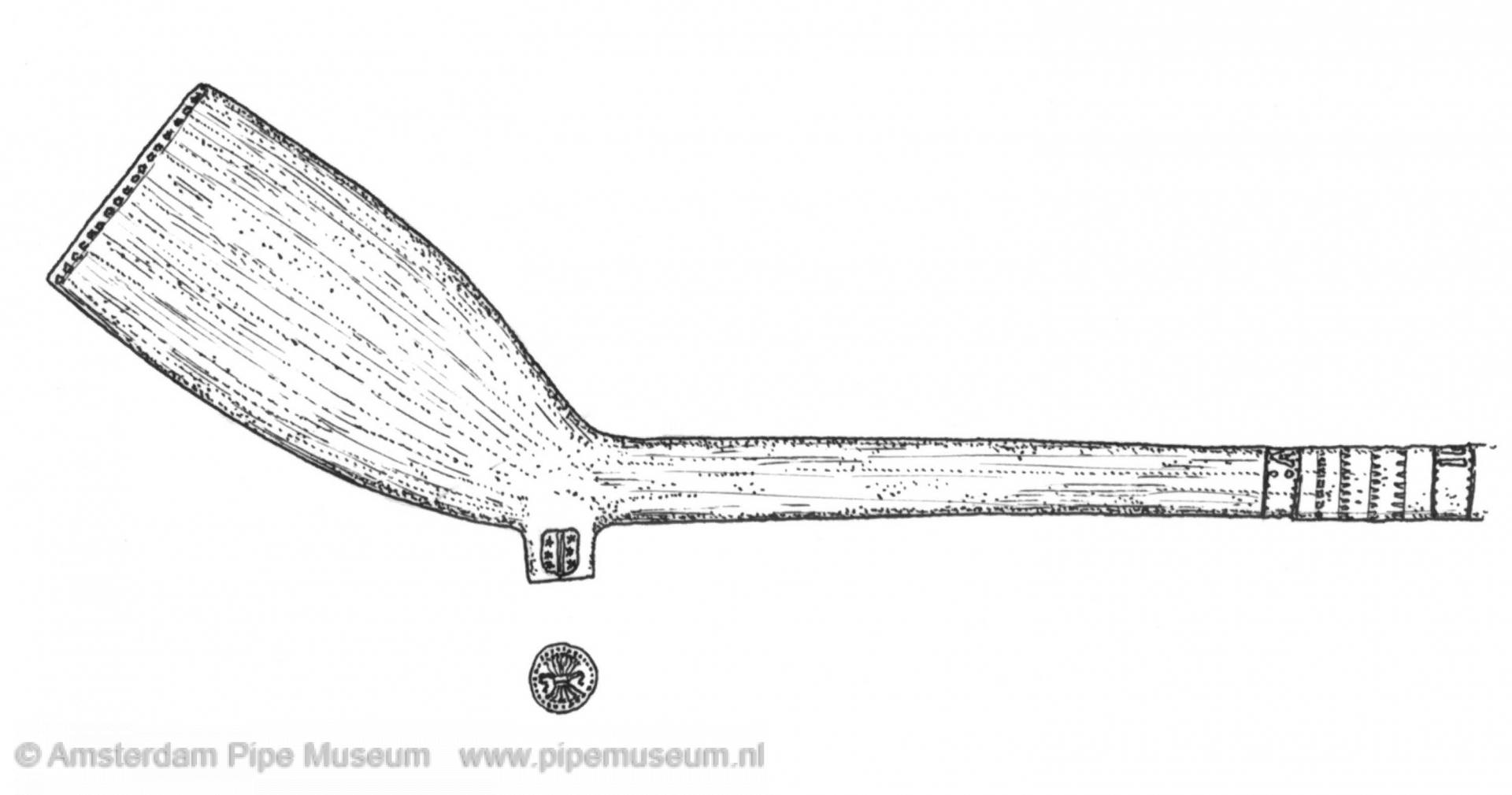

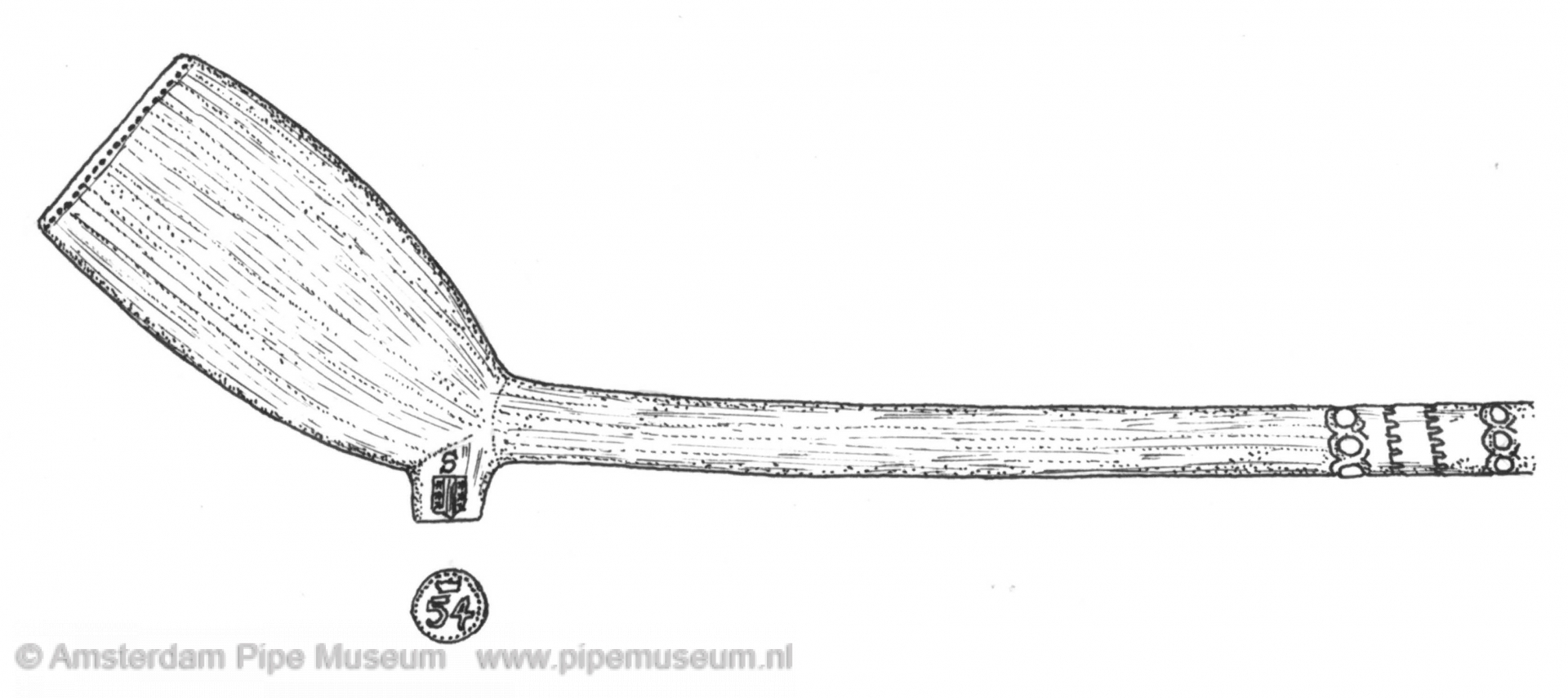

The better quality is more attractive. The shape is closely related to the development of the style. The quality can especially be seen in the finish. The milling is round the whole bowl rim, and there is always a heel mark. Also the pipe is polished, and there is a centre of gravity decoration applied. At the beginning this decoration is only on the top side of the stem (Figs. 1-2). From 1650 a gravity decoration goes right around the stem (Fig. 3), firstly in two bands, later in one band only. Some pipes are carefully finished, others are less nicely finished, reflecting the work of different manufacturers.

The evolution of basic type 1 is mainly the enlarging of the bowl size as tobacco is consumed in larger amounts. In the mid-seventeenth century the number of smokers among the higher classes increased and more attention was paid to the finish of pipes. A nicer quality of pipes was produced which had a stem ten to fifteen centimetres longer. This sold for a higher price. This third quality received the name "porceleijn" (literally porcelain). It is so-named to underline the fine finish and to indicate the fine, shiny structure of the material. Hence, this high quality pipe is compared with Chinese porcelain, although the raw material is certainly different. Basic type 1 was popular from 1620 until about 1680. Thereafter the bi-conical bowl type gradually disappears from the market.

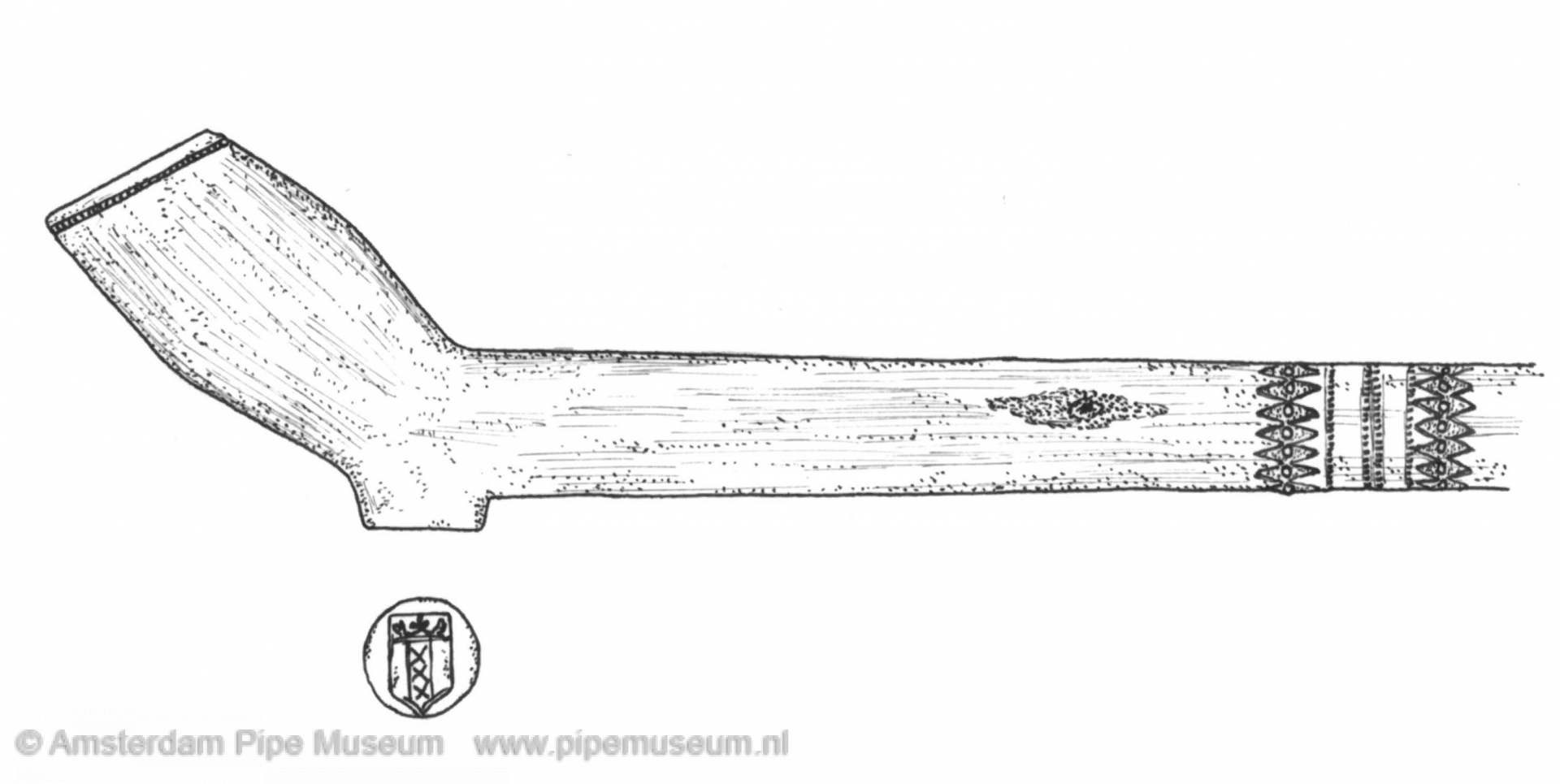

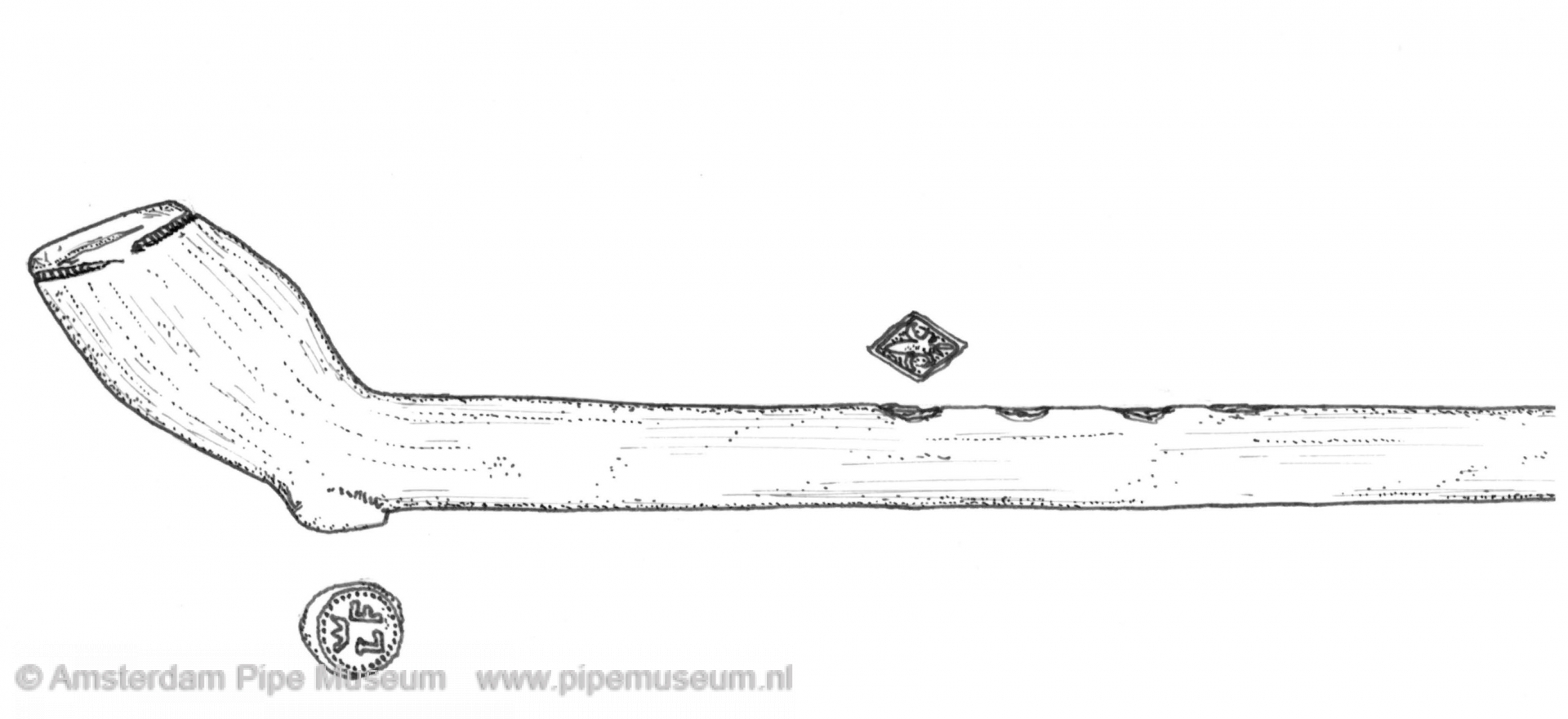

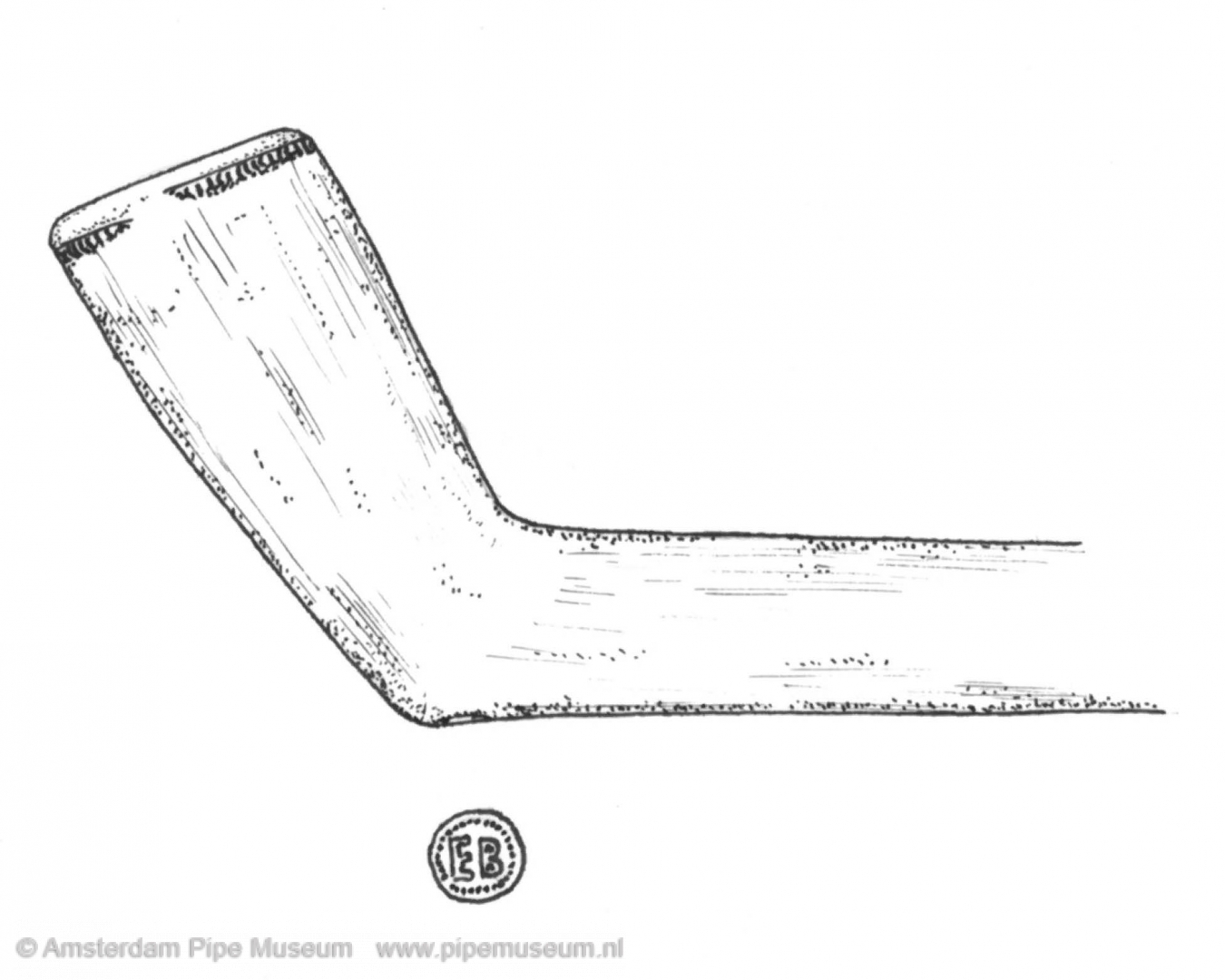

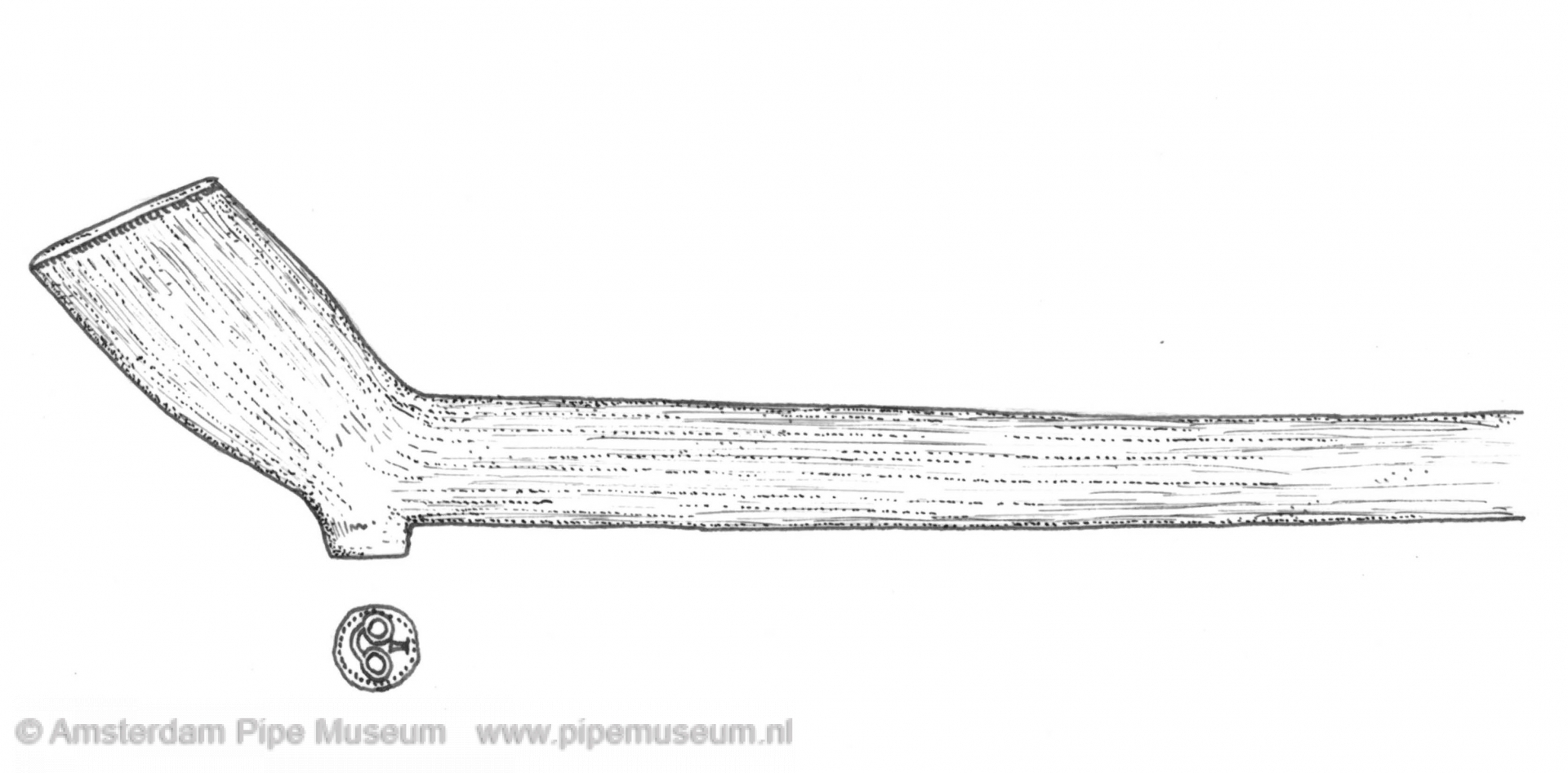

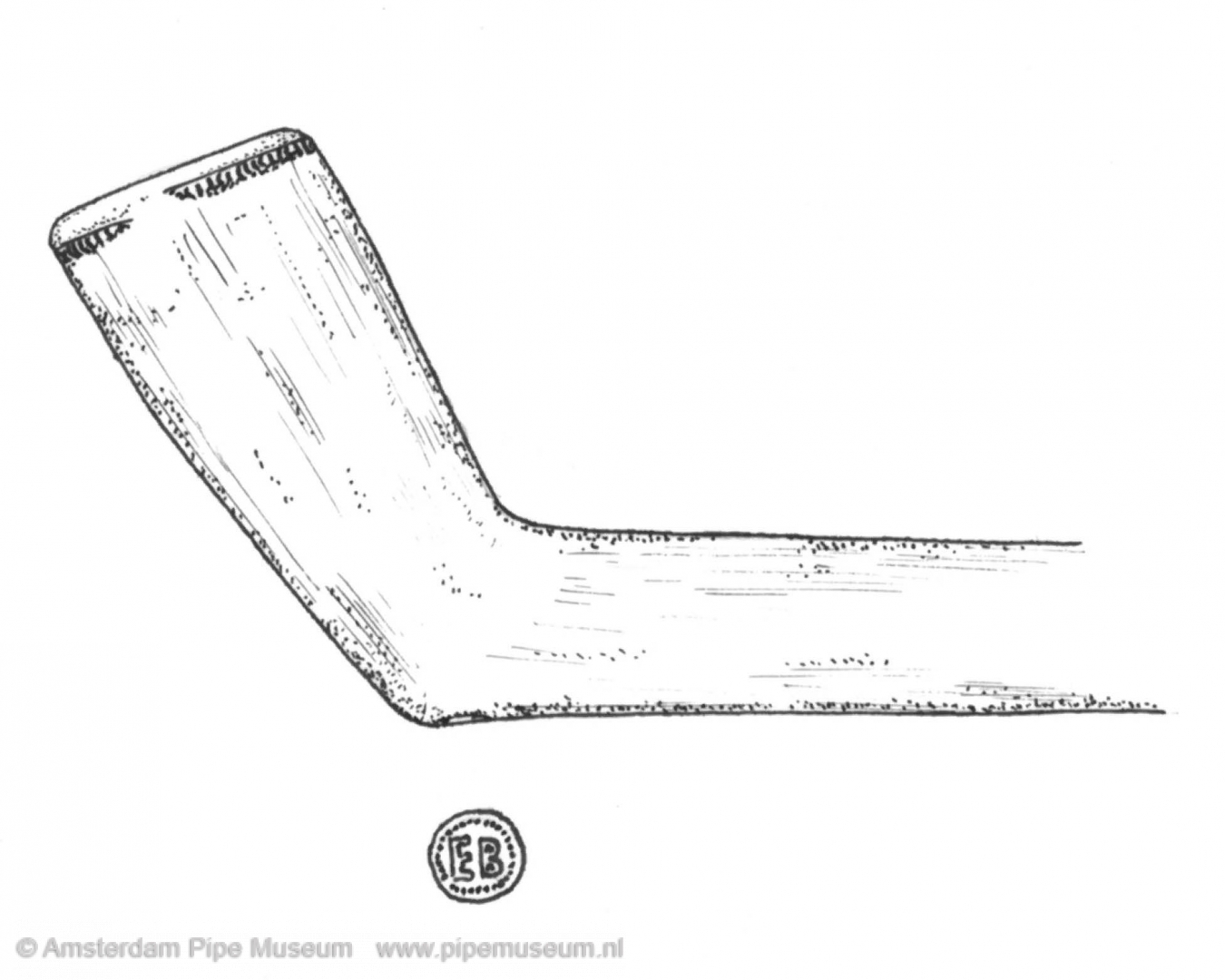

Basic type 2 (Figs. 4-5) is developed from basic type 1 and the evolution is meant to hold a larger quantity of tobacco. By widening the bowl opening the amount it can hold increases and the bi-conical shape is replaced by a funnel shape (Fig. 4). The indication bi-conical is restricted to basic type 1, whereas the funnel shape represents basic type 2. It is the funnel shape which makes it possible to use a thinner bowl wall, the bowl thus becoming lighter in weight which in turn means the stem can also be made thinner. This gives the pipe a more elegant look. The change in style took place slowly between 1680 and 1700.

Because of the refinement, the differentiation between the three qualities is more strongly defined. The fine, and porcelain quality are close to one another. The difference being that the fine pipe only has a polished bowl, the stem is never polished. The porcelain pipe however is polished all over, while after being baked, the pipe is treated with a white wax which makes it more shiny.

In contrast to the two better qualities the "grove" pipe has a less delicate shape, finally developing its own shape that is not representative of any fashion. By 1700 this type loses the heel to make way for the pointed spur. Sometimes a maker's mark is placed in relief on one side of the bowl. If there is any milling, it is only on the side facing the smoker. Basic type 2 does not have a long period of popularity and disappears between 1720 and 1740. In part we can think of this shape as the intermediary style between basic type 1 and 3.

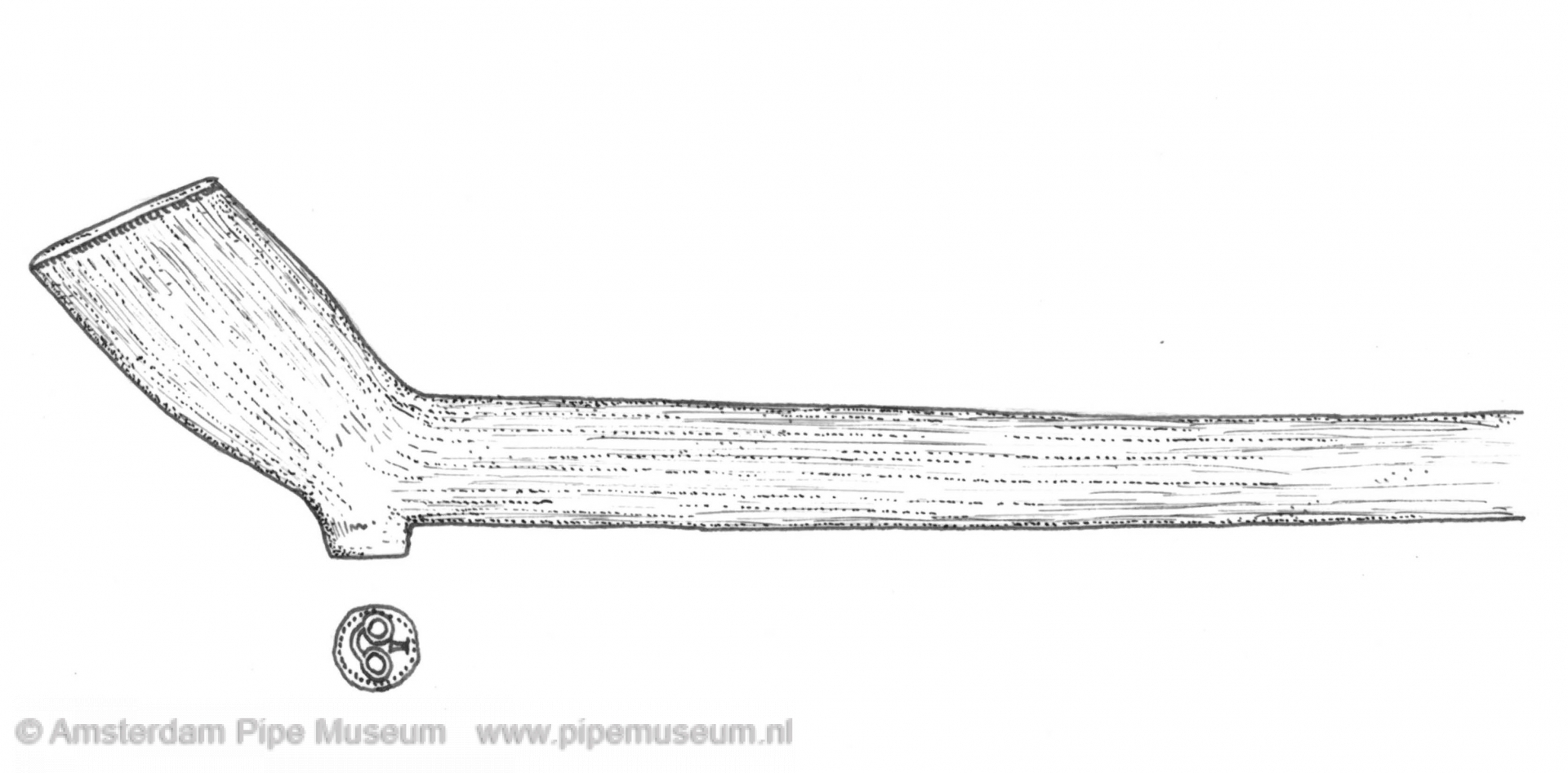

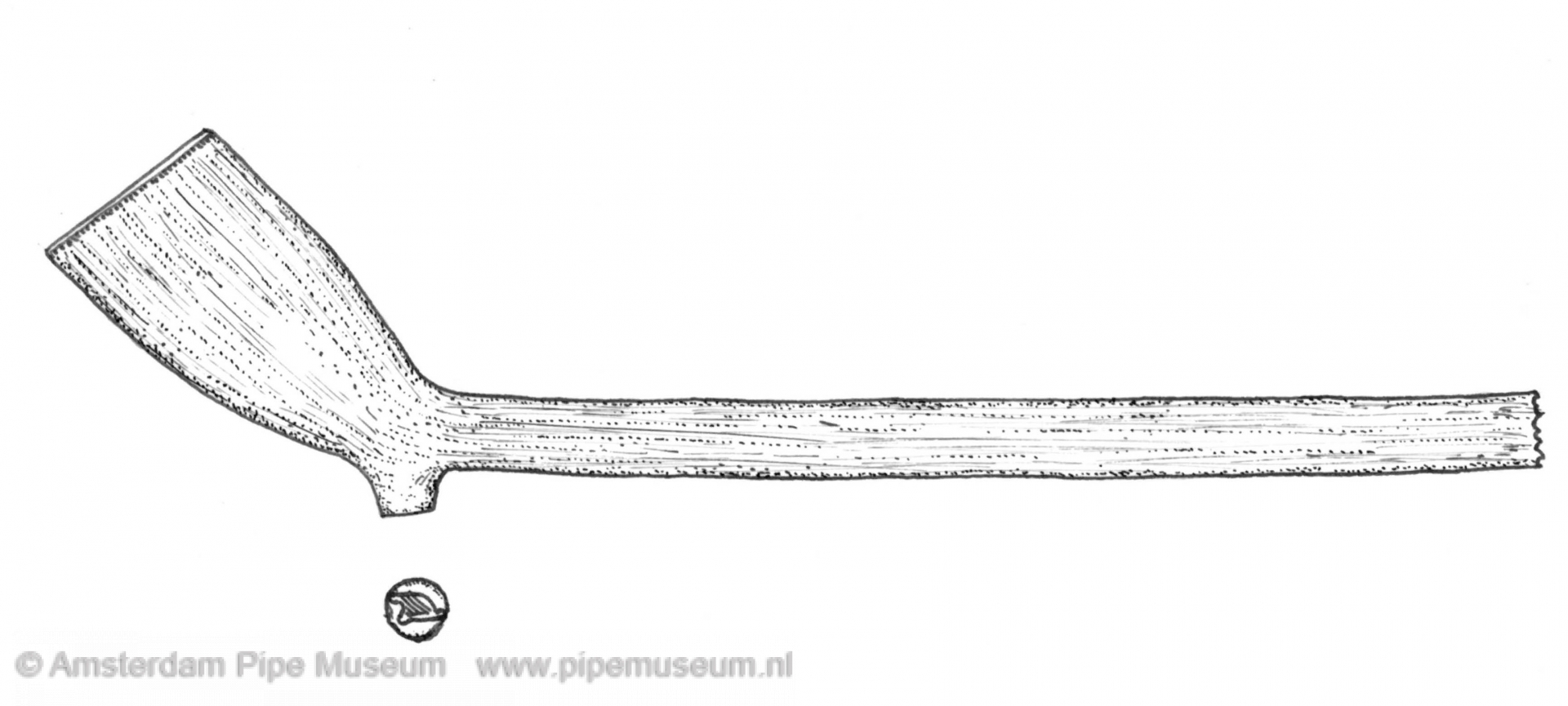

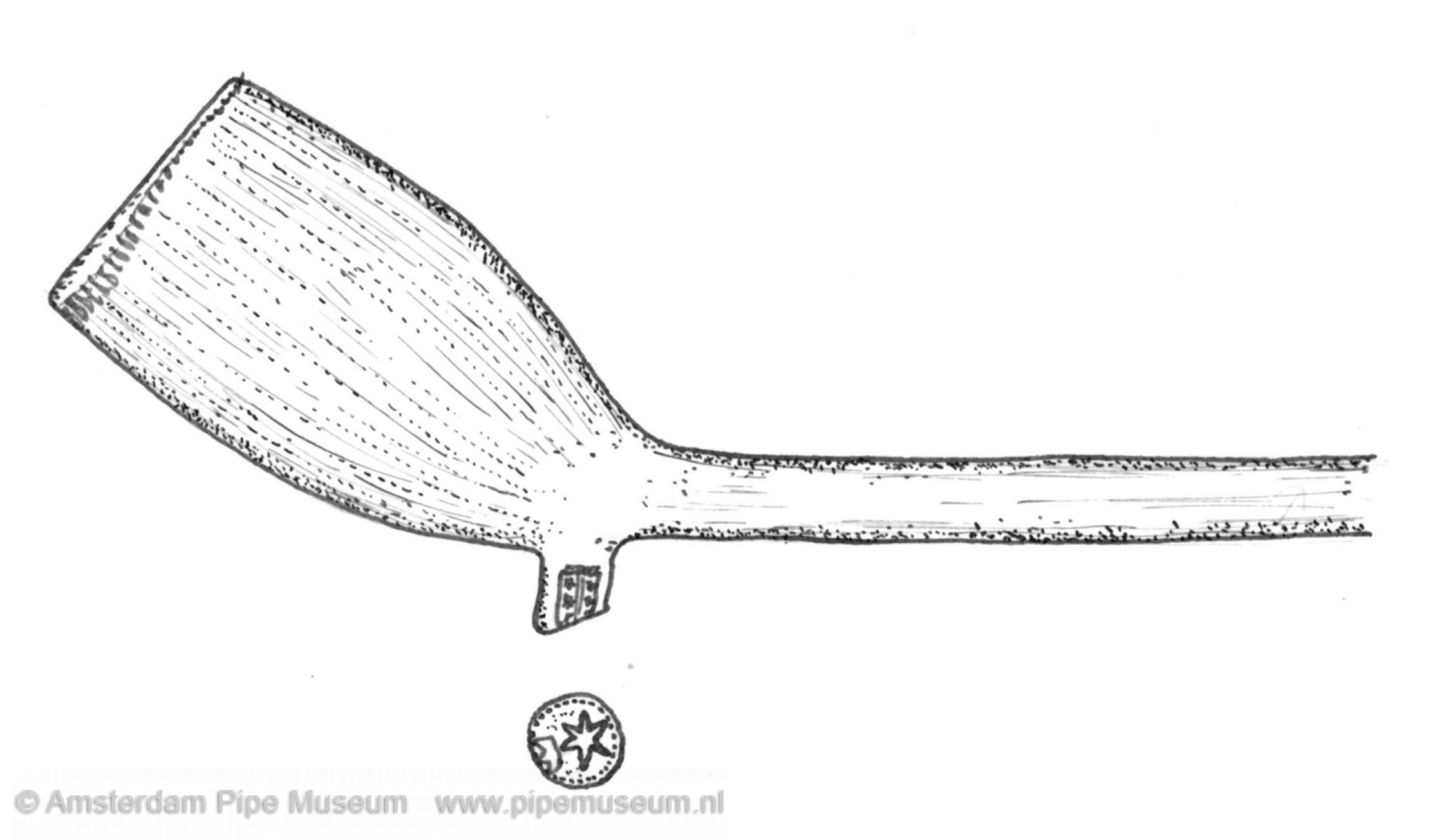

Between 1720 and 1740 the pipe bowl is enlarged again. This time by making the outline symmetrical. With this the perfect oval bowl type is born, basic type 3 (Figs. 6-7) and with this shape the Gouda pipe reaches its maximum elegance. At first the shape is not so strong being a slender oval. About 1740 the bowl becomes the full-grown oval shape, after which there are only changes in detail. When completely outbalanced, changes take place in minute detail only. This style is produced in various sizes, from large bowled, long stemmed up to one metre, to the miniature dolls-house version. Dating the pipe therefore must not take place on the basis of size, but on the slight variations in shape. Basic type 3 was popular until the mid-twentieth century.

The shape of the Gouda pipe together with the finish is so characteristic and standardized, especially after 1675, that it is hardly a problem to decide whether it relates to a Gouda product or a pipe from another centre. Careful attention paid to the characteristics that indicate a large scale production is one of the main starting points. In Gouda the complete handling during the manufacturing process reflects the same routine-like way. Certainly the eye of the researcher needs a certain amount of experience and the quality of the identification grows with the expertise of the researcher.

Basic types 1 - 3 can be fully credited to the merits of the Gouda pipe makers. In addition to these three styles several transitional shapes were made. This was partly in search of a new style but unfortunately today these intermediate forms make the dating of clay pipes more complicated. Shapes made for export were also manufactured in Gouda. These products were imitated or adapted to regional styles and examples of these will be mentioned in section 4 of this article.

Step 2: the Gouda imitation

When it is clear that the item to be identified was not made in Gouda we then proceed to the second step and see whether the clay pipe was made as a direct imitation of a Gouda pipe. The local pipe maker often tried to profit from the known quality of the Gouda makers by imitating their products. This maker could have worked in the area of Gouda but also in other parts of the Netherlands as well as in other countries.

For the experienced eye a lot of imitations are easy to recognize. In Gouda the production was carried out with the maximum discipline. Every product was made with the most accurate tools, by extremely skilled hands, and according to the strict guidelines that the various qualities had. The general appearance of the clay pipes shows harmony and balance, something which is very difficult to imitate by non-Gouda makers, not working on standardized mass production base.

Not being fully aware of the Gouda technique, lack of the right tools, and especially the lack of streamlined discipline, resulted in all imitations of Gouda pipes showing inaccuracies. Examples are a mould in which the correct cut-out design is not sharp, or the mould does not fit perfectly, an ill-working tool, or another problem which shows the lack of technical expertise.

As well as the pipe and the way it is made, it is useful to note all imaginable details. The local workshops imitate the Gouda pipe as a product of optimum quality, but they have not analysed the various aspects which make this quality. For instance, the engraving of the maker's mark is done differently. The engraving of the imitations often show a clumsy style, and does not have the same elegance of the Gouda engraving. In Gouda pipes, the heel-mark, side-mark, and mould mark are placed in a logic yet unobtrusive way. On imitation pipes, maker's marks are more prominent and less subtle. Also the spelling of the text on stems is not always correct. The name of the maker, and the town Gouda, are written with spelling mistakes or are on occasion phonetically. Letters in reverse prove that it is an imitation, and finally the word "fabricirt" (made by) or any variation of this was never used in Gouda.

Another important indication which uncovers an imitation is when the finish is not relevant to the quality of the pipe. The clear divisions in the quality of Gouda pipes has already been discussed. This is often neglected by imitators when they try to make one of comparative quality but miss out part of the process. In general products which follow the Gouda style are less delicate when they are produced further away from the town of Gouda. An important reason is that centres in the province of Holland and Utrecht could call upon tools and skilled labour from Gouda, when further away this is not possible. However the economic factor oversides all others. The further away from Gouda the higher the transport costs hence the more expensive the pipes. The regional imitation may be of lower quality but it is also cheaper because of low transport costs and lack of eventual duties.

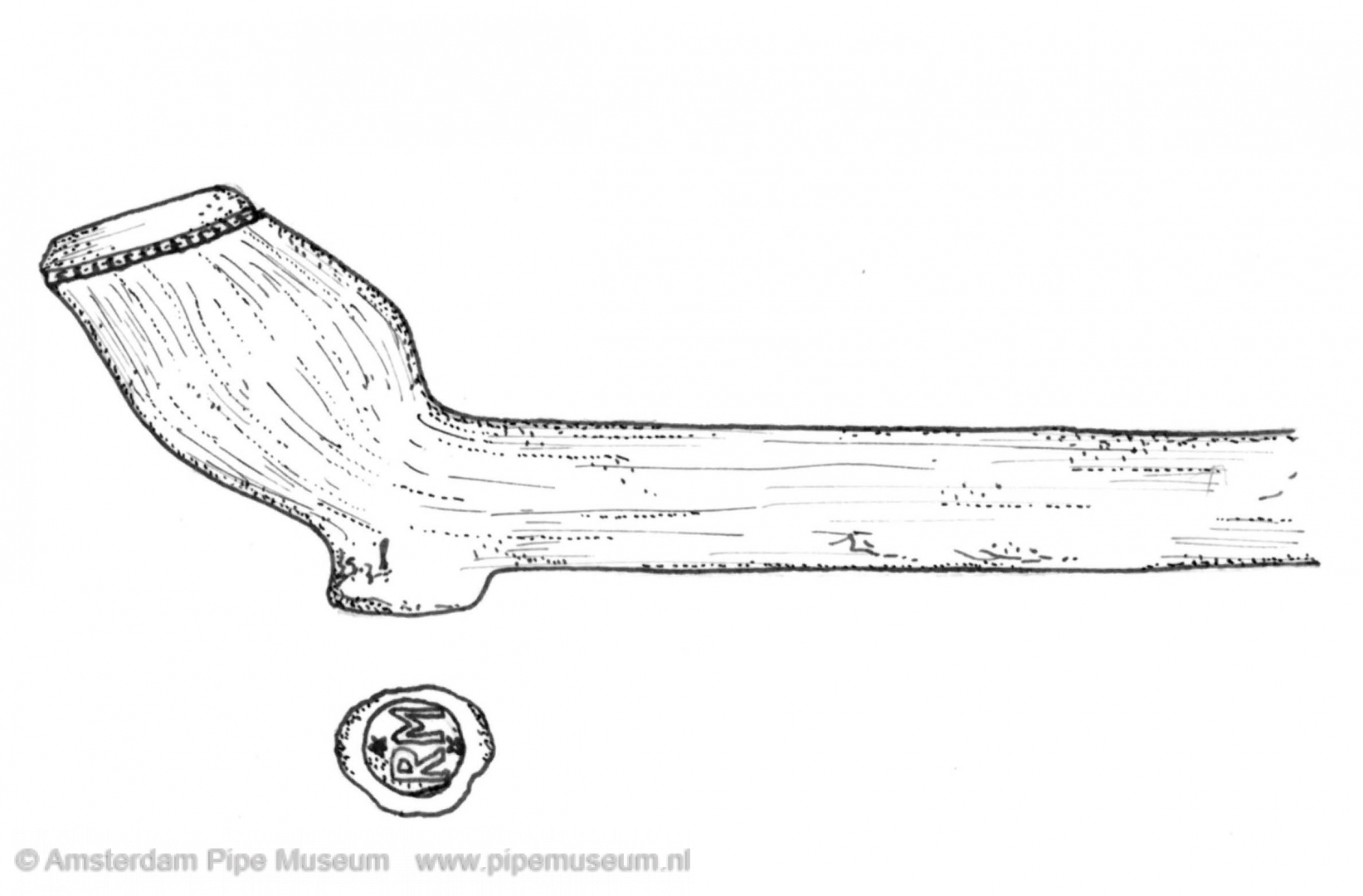

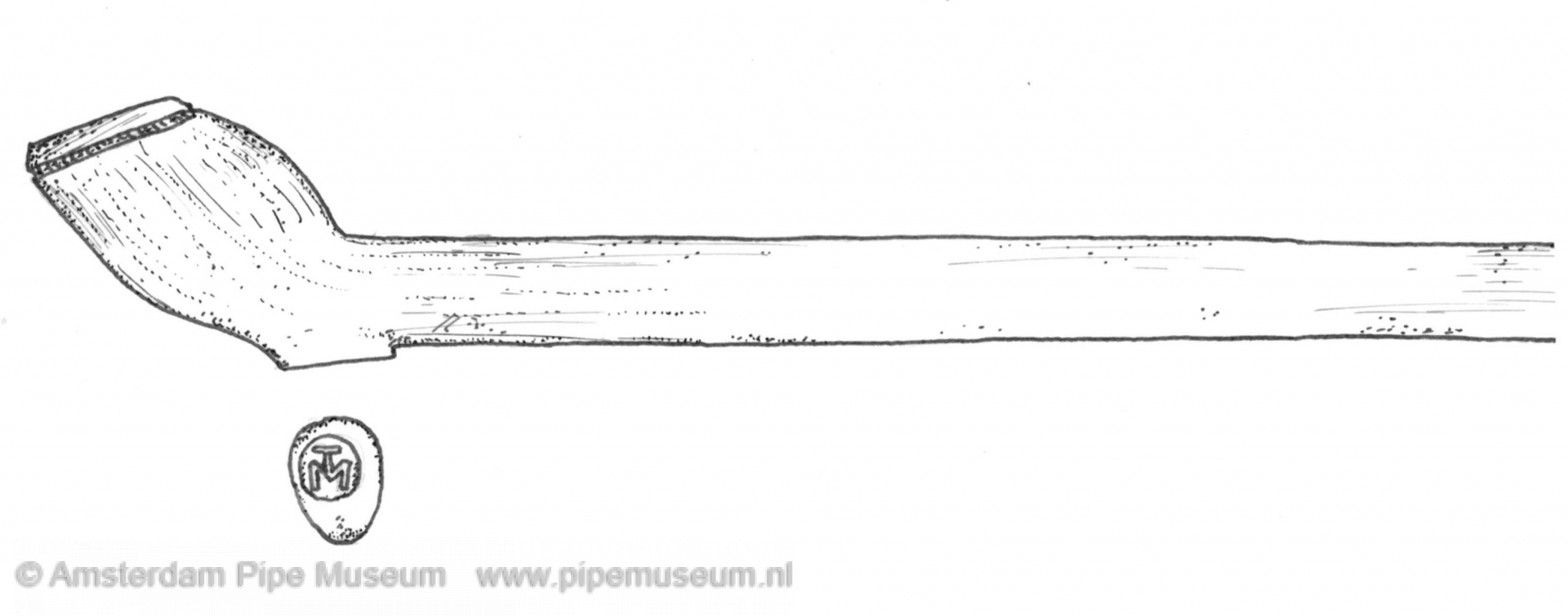

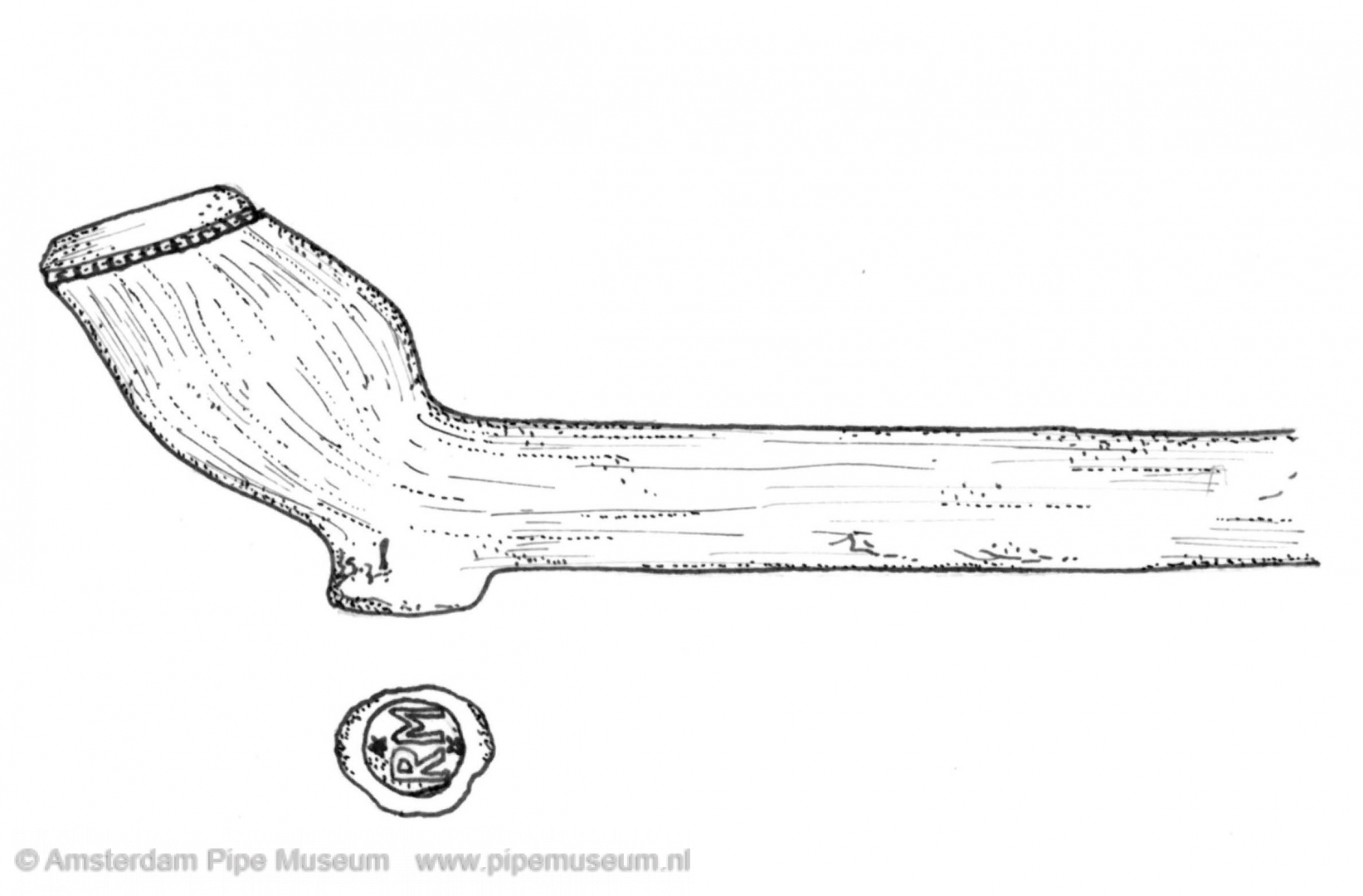

Imitations of Gouda pipes are known including examples from all three basic types. Basic type 1 has the most variety of shapes, and it is questionable whether these pipes should be classed as imitations or interpretations. Some examples are illustrated here. A clay pipe from Amsterdam (Fig. 8) has the Gouda pipe characteristics which apply to that period, except the polished finish and the gravity decoration. The maker's mark is typical of the workshop, that is not imitated but showing the initials of the Amsterdam maker.

The Alkmaar pipe (Fig. 9) shows more local characteristics, i.e. a stronger bi-conical bowl shape, but still is a copy of the Gouda style. Again the maker individualized its product. The Breda version (Fig. 10) more closely resembles the Gouda examples, including the gravity decoration and the polishing, still this pipe is less fine than its Gouda counterparts.

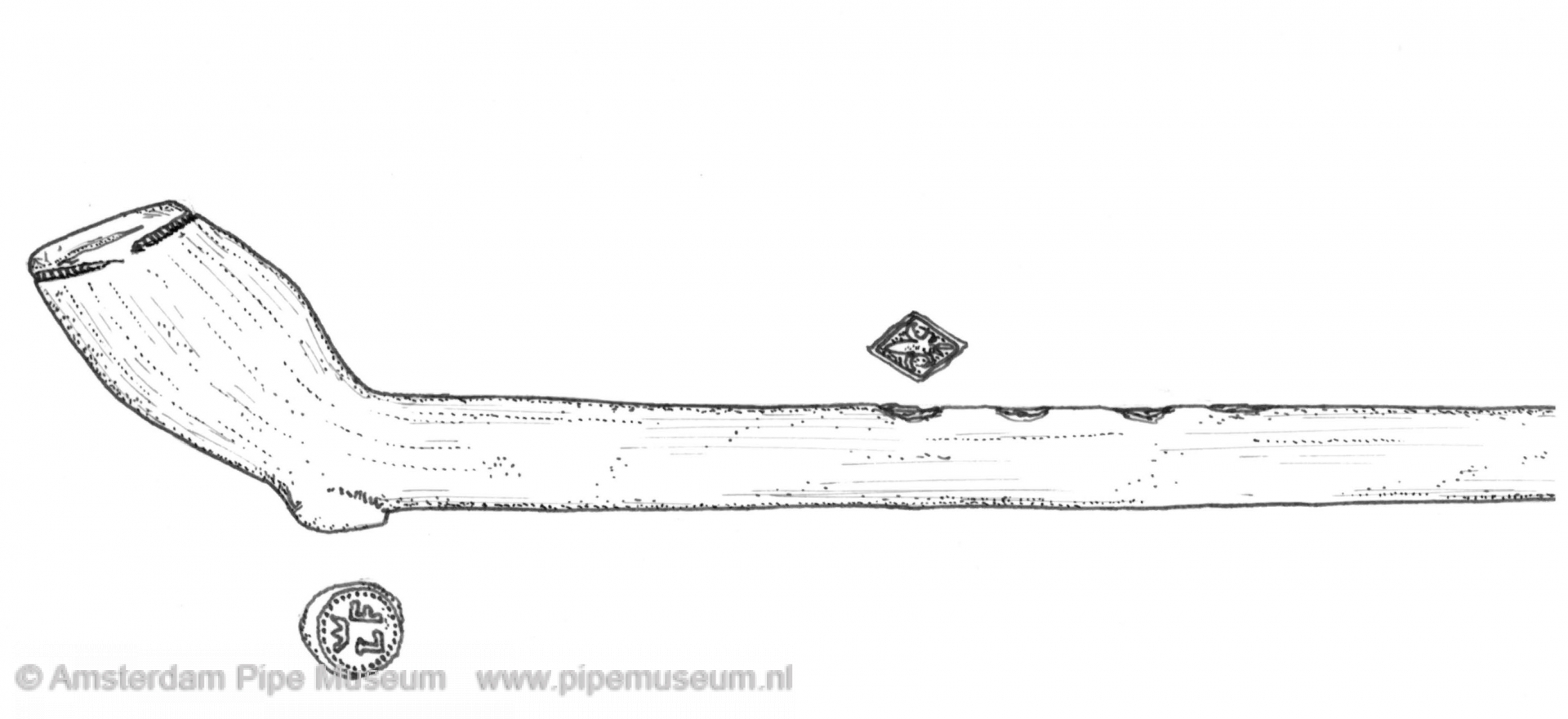

For basic type 2 an imitation from Gorinchem is illustrated (Fig. 11). Here the Gorinchem pipe maker has carefully copied the Gouda example. The heel-mark however gives away the fact that it is an imitation because the engraving is not as fine as that known in Gouda.

Especially of basic type 3 there are a large number of imitations. With this shape the Gouda pipe reached its greatest perfection, and this pipe is used all over the world. One of the most interesting imitators of the Gouda pipe is Philip Hogenboom from Alphen aan den Rijn, a village only 15 kilometres to the north of Gouda. His workshop flourished between 1745 and his death in 1764, and Hogenboom not only bought his tools in Gouda, but also obtained his labour from there (note 2). Therefore his clay pipes are very difficult to distinguish from original Gouda ones (Fig. 12). Only a minor variation in the Gouda coat of arms can be seen. This emblem was protected in the province of Holland and therefore could not be used without incurring punishment. Hence Hogenboom put one or two extra dots in the centre band of the arms to escape legal issues.

When we compare this pipe with one from Groningen from the same period (Fig. 13), we note that the shape is less sharp and the finish is not as fine. The heel-mark shows the crowned star, a mark not in use in Gouda in that period.

Basic type 3 was also copied in many other parts of Europe: French, German, Polish, Russian and others are known. An example from Zborowskie in Poland is illustrated here (Fig. 14). Here copies of Gouda pipes were made but again some of the characteristics are different. Firstly the bowl-shape is a little higher and more mechanically round in addition to which a completely different way of marking the pipe is used.

The production of basic type 3 continues in the nineteenth century. Again the oval Gouda pipe is subject to imitation. Because of the declining quality of the pipe it is no longer the fineness of the material and the finish which is a guarantee of a Gouda pipe. It is the unified style of the Gouda workshops which mark out these pipes and those who are familiar with the style will always recognize this and identify imitations from elsewhere. As already stated, this section will not be included in this article.

Step 3: the local style

Besides a desire to imitate the Gouda shapes the interest exists to design pipes according to the local style or fashion. As soon as a local maker adds his own peculiarity to the pipe shape we no longer speak of it as an interpretation or imitation but as a creation. Many particular shapes however are not designed by pipe makers but are the work of a mould-maker. When they make a mould they always use the same basic style, which automatically meant the birth of a local or regional style.

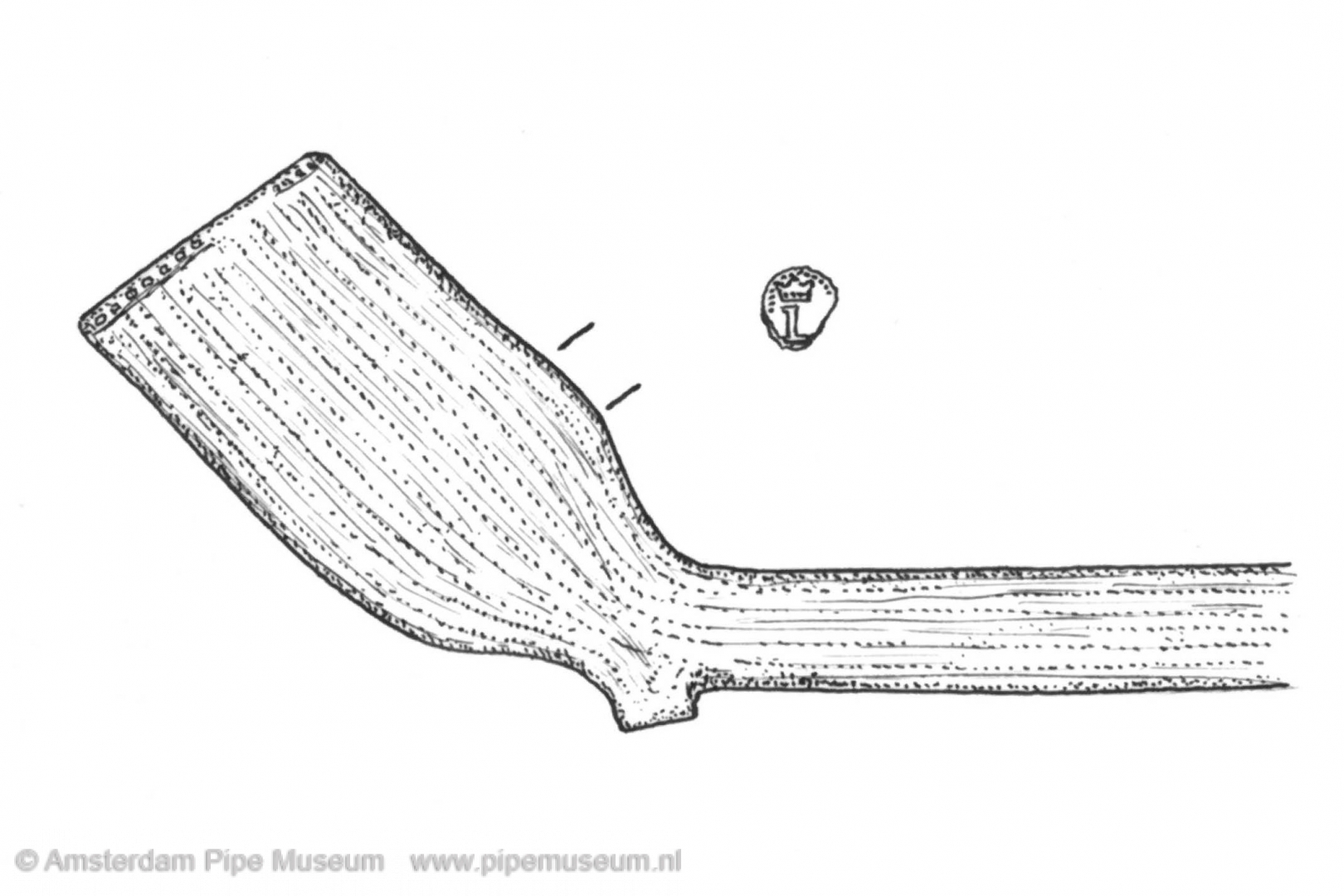

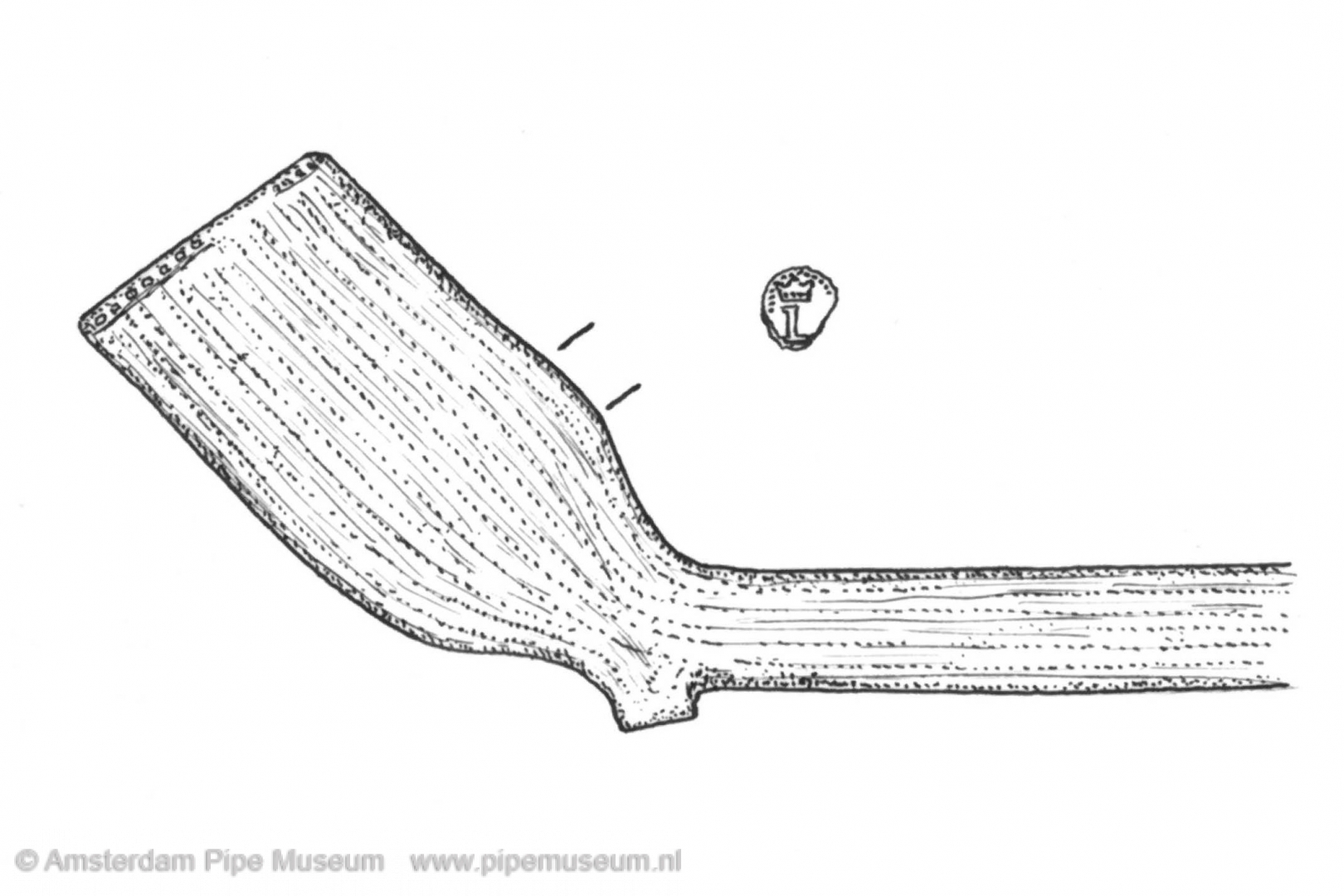

In a great many cities a local style exists. A representative example from the area of Gouda is the Leiden pipe shape (Fig. 15) which was made between 1650 and 1675 by pipe makers in that town, 30 kilometres away from Gouda. The main characteristic here is the strongly bulbous profile of the bowl at the stem side combined with the slightly flattened bowl sides. The Leiden style we can fully credit to the local working mould-maker and this model has not been copied in other cities.

Workshops in Groningen, in the northern part of Holland also show their own characteristics (Fig. 16). Here the profile of the bowl of the bi-conical Gouda shape changes into a rounder, less elegant shape. Also the angle from the bowl to the stem is smaller. Again this change was brought about by the mould-maker who made moulds for various Groningen pipe makers. Another reason for this rather crude local style is of course the poor quality of the pipeclay in this part of the Netherlands.

Local styles may either be creations of slightly different pipe styles as well as completely new inventions. The latter originates from local recipe of the tobacco, relating as well to the blend as the cut of the tobacco in a particular place. Since a certain blend or cut has a specific taste a particular type of pipe is designed to support that taste. Spread over Europe we find a great many different local styles, originating from local fashion and local tobacco recipes. This together with the local level of manufacturing techniques influences the local shapes.

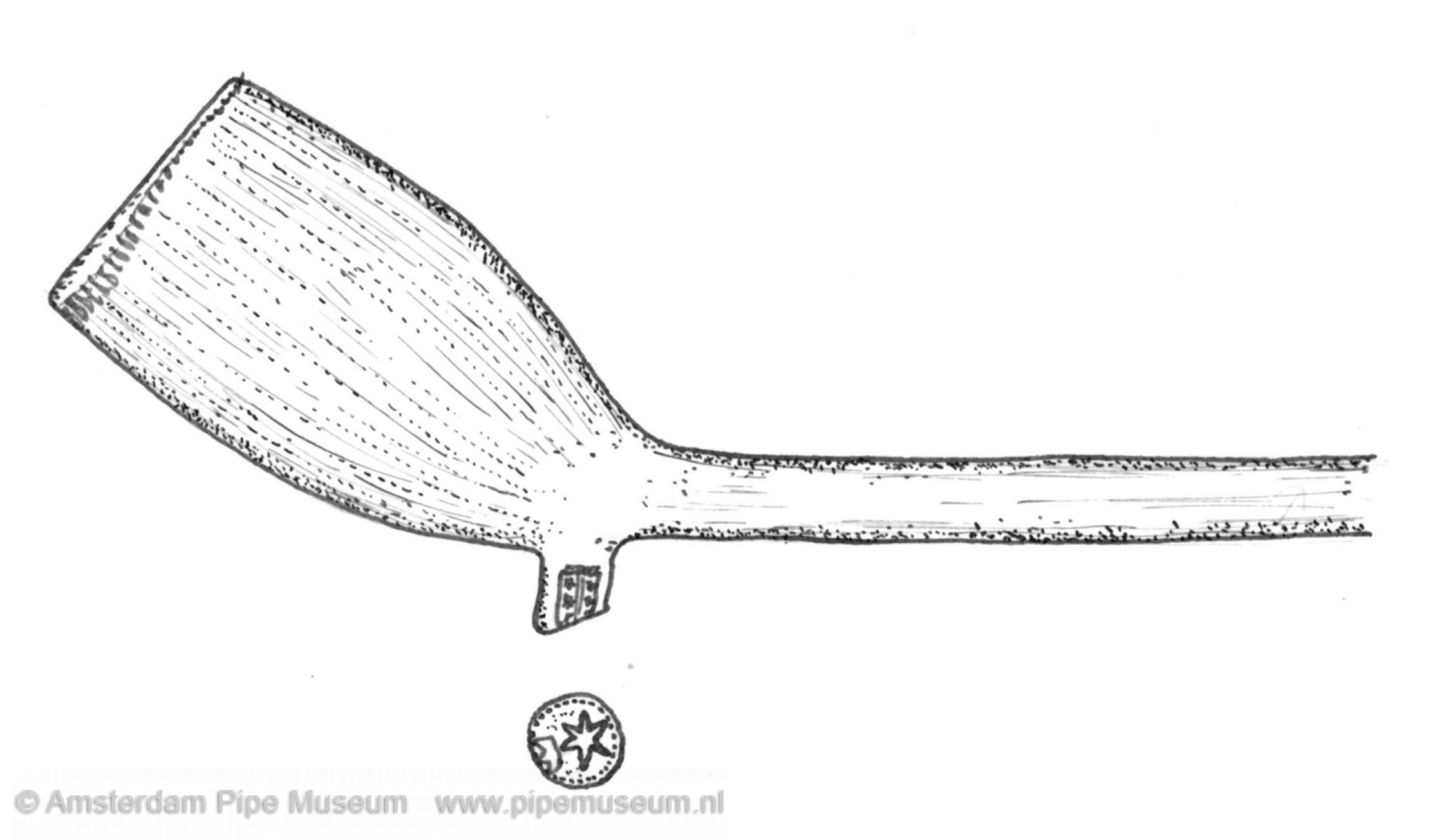

In Germany at Westerwald for instance pipes with a specific beaker shape come in production (Fig. 17). However it is still undiscovered whether this style originates from this part of Germany, the beaker becomes the popular shape during the period 1750 to 1900. As export pipe it reached an international popularity.

The English styles of clay pipes (Figs. 18-21) seem to develop separate from the European styles. The most remarkable is the Salisbury style (Fig. 18), showing an s-shape in the bowl. More general bowl styles are the so called spur type (Fig. 19), the straight sided bowl (Fig. 20) and the south-eastern bowl (Fig. 21). These bowl styles have been produced in large quantities in many parts of Great-Britain.

When a local design is successful this new style is then reflected in other areas. Of course, the maker encourages this and good promotion of his particular style may generate a demand for his products beyond that of the pipes in general use. In this way the basis for a flourishing workshop is founded. The next that happens is that in other regions this style is copied.

Sometimes a pipe maker or potter designed a pipe which was completely free from previous conventions. One of the best examples of this is the sub-stemmed pipe which was developed in eastern European countries (note 3). This shape was produced in an area lacking in technology. Not having the right kind of raw material it was impossible to make a full clay stem. This type has remained popular over the ages being produced by several European pipe makers and also some potters in the West-European countries.

Step 4: influences from other centres

When a pipe is not from Gouda, and it is not an imitation Gouda pipe, or a local invention it will either be influenced by other regions or a combination of influences from several other regions. The mixture of influences we name cross-pollination. These shapes vary between precise imitations of local styles till the following of styles that in some cases lead to new merits. There is no sharp division between clay pipes from categories 3 and 4. What is important is to point out the level of local input and merits from other regions. A debate on who is the inventor is not really of any use, simply because often in many areas the same types were developed in the same time.

The copying of a local style in another place is the most simple in this category and many examples are known of this kind of imitation. In fact this is the imitation on the same level as the Gouda imitation in step 2. Sometimes the imitation of the pipe style is slightly altered so that a new style emerges. Rarer are interpretations showing elements of various regions.

An early and interesting example of an interpretation is the so-called elbow-pipe (Fig. 22), a specific shape which was produced in Amsterdam as a trade item to the American state of Virginia and the surrounding areas. The profile of the bowl is based completely on the local Indian pipe, however the material and finish are Dutch inspired. Therefore this pipe is a Dutch interpretation of the local American style.

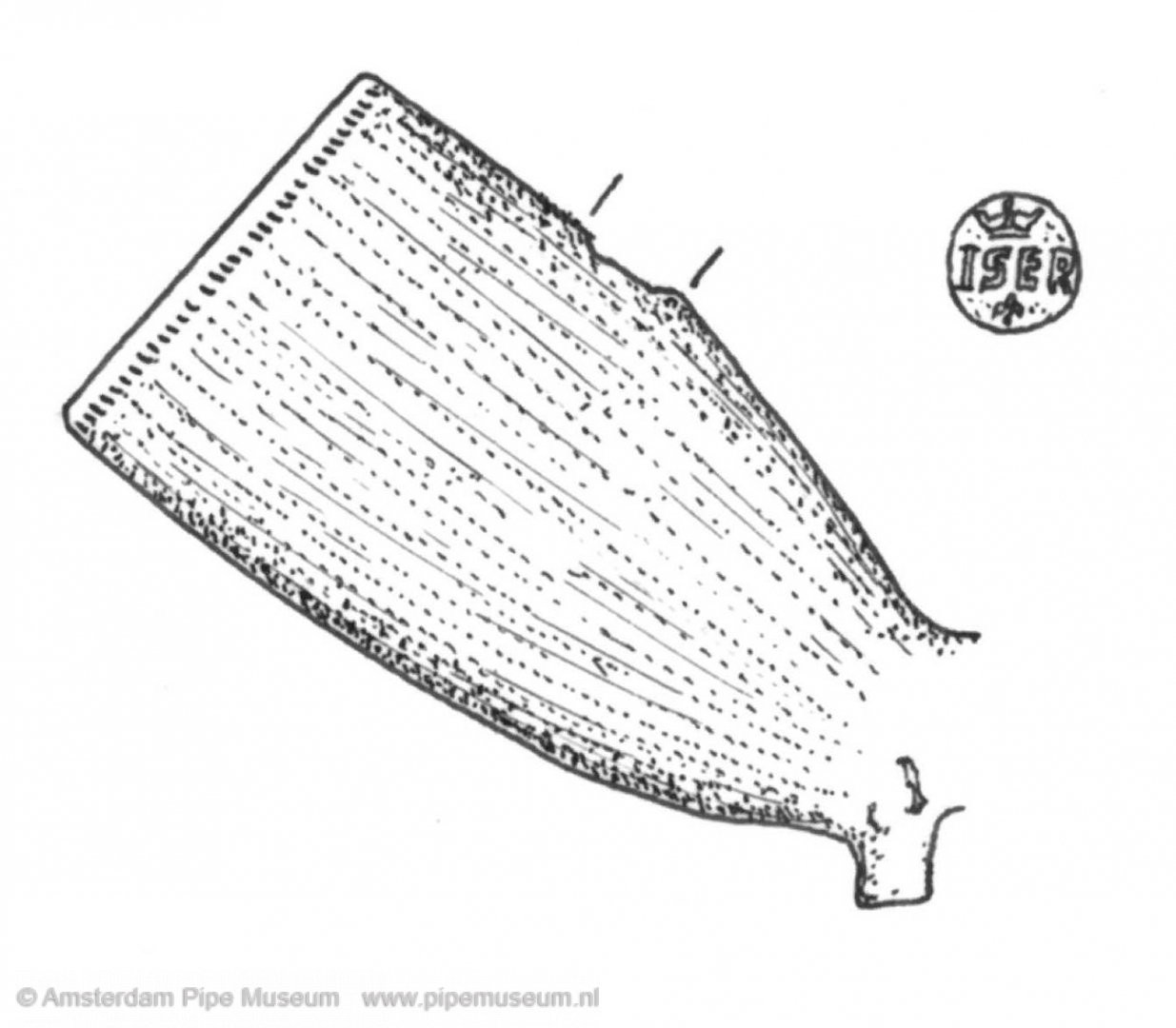

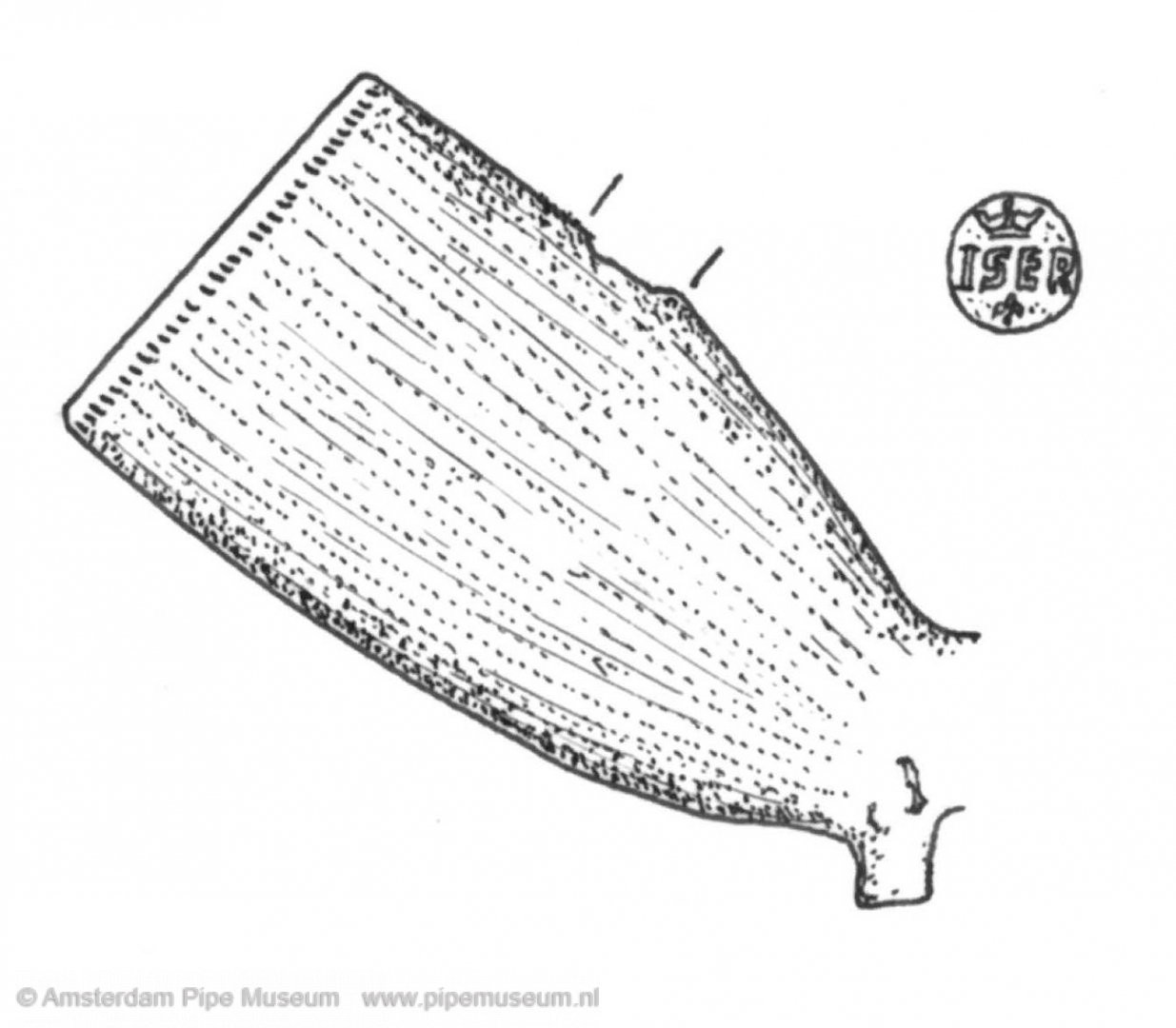

An interesting example of an exact copy is a pipe from the Hildesheim maker Johan Iser, the copy being made by the before mentioned Philip Hogenboom in Alphen aan den Rijn (Fig. 23). Shape, finish and marking are from the same discipline as applied in Hildesheim. If this pipe had not been found on the factory dump the imitation would never have been discovered.

Another copy of a German pipe originates from the workshop of Pieter van Wijngaarden again working in Alphen aan den Rijn (Fig. 24). The beaker shaped bowl and also the fish decoration resemble the German counter products, but the makers mark demasks Van Wijngaarden as imitator of the German style.

A production area which deals in exports, the so-called supra-regional centre often produced several styles side by side. Alongside the local market, makers also produced pipes for the export market where they made styles suitable for the customer in that region.

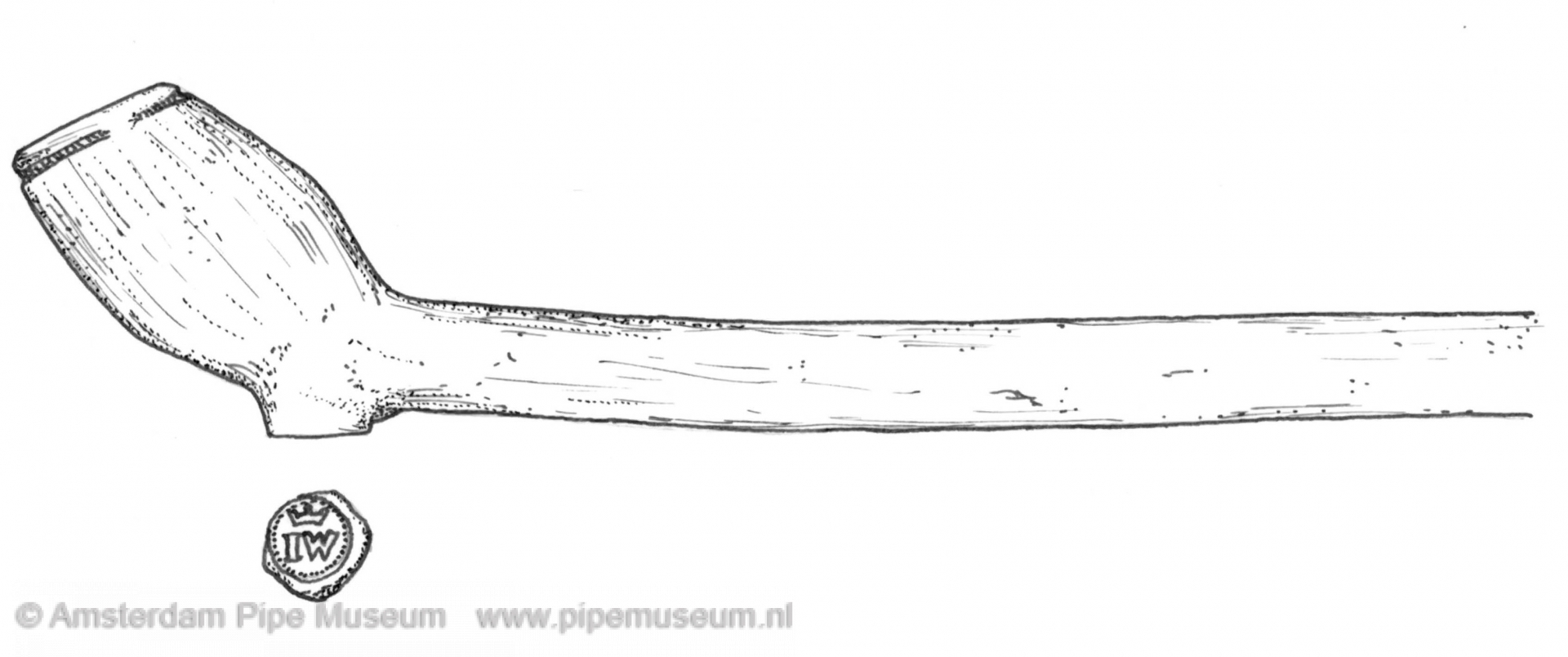

Certainly Gouda can be placed among thosAfb.e cities which made pipe shapes for the export market. In fact, basic types 4 and 5, the curved bowl and the round-bottomed bowl (note 4), are shapes of which the origin lies in other areas, namely England and Germany. The style of these bowls has however been slightly changed so that we can credit them to Gouda, although the basic shapes come from elsewhere. For exportation to the north German states an elongated bowl is produced (Fig. 25) of which the style is introduced in the Hamburg area by local makers. The production of these shapes became of supra-regional importance and often Gouda makers offered these styles to merchants in other countries as well. Hence these export pipes influenced pipes in other regions.

Among others, some so-called south-eastern shapes from England are copied in Gouda (Figs. 26-27). These shapes are an interpretation of the English counterparts and the change in shape caters for the taste of the region to which the pipes are meant to be exported. The disciplined way of finishing in the Gouda workshops resulted that the pipes were finished in the typical Gouda way. They have a heel mark, a side mark, milling and also a glazed surface. A finishing that is not generally applied in England, however common in Holland.

An example of an export pipe from Gouda, after the English type, but destinated for Poland is one with a curved bowl (Fig. 27) showing on the stem-side of the bowl the mark WM crowned in relief. The shape of the pipe is obviously English of origin, however the finish is in the Gouda tradition. This is clearly expressed by the engraving of the mark, the heel-side mark, and the glazing of the pipe, also the milling.

Finally the style of the English clay pipe was copied in about 1770 by Adolf Forsberg in Stockholm (Fig. 28). His products however show some personal characteristics but the basic type is definitely copied from the English pipe.

Because of the growing pattern of trade routes and the larger variation of shapes the influences become more complicated during the course of the eighteenth century. After the three Gouda basic shapes have spread their influence worldwide, there is a counter-reaction. Some of the reactions from English workshops, the Westerwald region and various French places have been indicated in this article. Moreover there are still many undiscovered lines of influences. Even Asiatic, African and native-American clay pipes play their role in the influencing and spreading of shapes.

In the nineteenth century the types for export become more important. From the many influences an immense variety of styles and shapes of pipes emerges, which often makes it difficult to discover the origins of them. We can therefore certainly speak of an international style, while some types can be traced back to the eighteenth century origins. The famous Dorni-pipe for instance, of which the origin lies in Germany, is such an example. This clay pipe is produced during the entire nineteenth century in Gouda, but also in the Belgian town of Andenne, while production in Germany at Westerwald also continued (note 5). The main export destination is the United States, but these pipes are also smoked in various European countries.

Many pipes that have various influences on their style are made especially for an export order. This specific order sometimes lasts for only a short time simply because a trade contact is temporary blocked or because production becomes more economic in another area. Under the influence of open or closed routes and affected by monetary changes the export orders change from one region to another. They are placed where the proportion of the industry is sufficient, and the price is competitive.

Conclusion

Clay tobacco pipes can be the main source of dating for other finds. They can also be used for additional information. To identify a pipe requires a lot of knowledge, insight, and above all care. This article poses a major question: to which style does the pipe being identified belong. The answer lies in a typology of four groups: the original Gouda style, the Gouda imitation, the local style and influences from other centres. However it is not the discussion to which group a pipe belongs, but mainly the careful analysis which leads to a wellfounded identification.

This article tries to place the pipes in the context of their shape. During the analysis of the pipe shape a well founded opinion on the influences of various production centres is obtained and a division in groups emerges. This information leads to a better understanding of the pipe in question.

When in the future the study of clay pipes continues, and systematic research is carried out we will certainly have more insight into the history of the European clay pipe. It is then time for a final publication on the development of the bowl shape from the various European workshops.

This future phase wil certainly not be the final phase of pipe research. This will be followed by study to gain more interpretative information. How fashionable is the pipe or does it concern a conservative example. What is the significance of a particular makers mark or decoration. How was the clientele built up. What can we tell about the trade relations and the pattern of market-supply, etc. Answering this new series of questions will increase the quality of information which a clay pipe can offer making it an even more valuable tool for interpretation.

Don Duco (Amsterdam, 1953) studied history of art and museology in Leiden, Holland. Since 1969 he collected and studied clay pipes resulting in various publications on this subject. His book De Nederlandse kleipijp, the handbook for Dutch clay tobacco pipes is till now his main publication. Duco is curator of the Pijpenkabinet, the national pipe museum, since 1995 housed in Amsterdam (Prinsengracht 488, NL-1017 KH).

© Don Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Amsterdam – the Netherlands, 1999.

Description of illustrations

The original Gouda style

- Holland, Gouda, IC-maker, 1630-1640.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 1.525

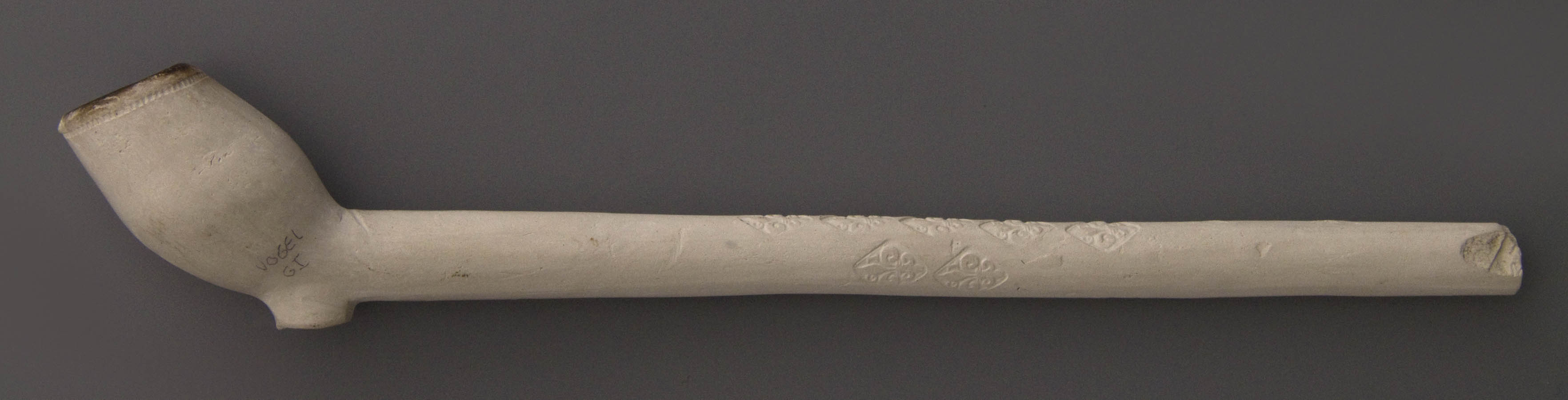

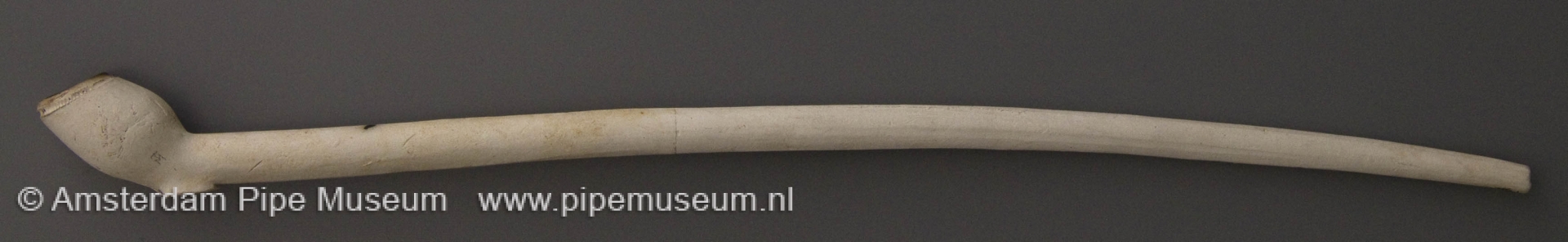

Fig. 2. APM 1.440 - Holland, Gouda, GI-maker, 1635-1650.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 1.440

Fig. 3. APM 19.567a - Holland, Gouda, 1660-1675.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 19.567a

Fig. 4. APM 3.471a - Holland, Gouda, 1670-1680.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 3.471a

Fig. 5. APM 4.581 - Holland, Gouda, Jan Sodaen, 1720-1730.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 4.581

Fig. 6. APM 2.642c - Holland, Gouda, Albertus Damman, 1740-1760.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 6.242c (Pk 2.013 fout)

- Holland, Gouda, 1770-1790.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 915a

The Gouda imitation

- Holland, Amsterdam, TM-maker, 1630-1640.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 7.669b

Fig. 9. APM 15.035a - Holland, Alkmaar, Robert Morijs, 1635-1655.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 15.035a

Fig. 10. APM 15.354a - Holland, Breda, Louis Fieliep (Philips), 1660-1680.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 15.354a - Holland, Gorinchem, 1700-1720.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.408a

Fig. 12. APM 10.277 - Holland, Alphen aan den Rijn, Philip Hogenboom, 1745-1770.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk b.96 - Holland, Groningen, 1750-1780.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.27 - Polen, Zborowsky, Fabrike in Silesia, 1740-1780.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 14.066h

The local style

- Holland, Leiden, Joris Wright, 1655-1670.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 13.549

Fig. 16. APM 7.448a - Holland, Groningen, David van Hoornbeek, 1670-1690.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 2.464 - Germany, W.H. Remy, 1780-1810.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk b.118 - England, Salisbury, 1650-1670.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 7.273 - England, 1660-1680.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 4.519 - England, 1690-1715.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 4.757a - England, 1710-1740.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 4.784

Influences from other centres

- Holland, Amsterdam, 1655-1680.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 9.568a

Fig. 23. APM 8.691 - Holland, Alphen aan den Rijn, Philip Hogenboom, 1745-1770.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 8.691 - Holland, Alphen aan den Rijn, Pieter van Wijngaarden, 1780-1800.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 16.337

Fig. 25a. APM 9.568a - Holland, Gouda, Cornelis/Jacob de Licht, 1730-1750.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 1.099a

Fig. 26. APM 1.099a - Holland, Gouda, Frans Verzijl, 1750-1770.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk b.117 - Holland, Gouda, Frans Verzijl, 1760-1775.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk b.130 - Sweden, Stockholm, Olaf Forsberg, 1760-1775.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 8.847a

Notes

- H. Duco, De Nederlandse kleipijp, handboek voor dateren en determineren, Leiden 1987, pp. 26-28.

- Don Duco, "Alphen als concurrent van de Goudse pijpmakers", Pijpelijntjes, X-4, 1984, pp. 3-6.

- Don Duco, "Turkije als centrum van de Oost-Europese pijpenfabricage", Pijpelijntjes, X-3, 1984, pp. 1-8.

- Duco, op. cit, 1987, p. 27.

- Don Duco, "Veertig jaar speculaties rond Peter Dorni pijpen", Pijpelijntjes, VII-4, 1981, pp. 1-8.