Book review: Forgotten glory: The economic development of the Dutch clay pipe industry in the 17th and 18th centuries

Author:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Boekbespreking: Vergeten glorie: De economische ontwikkeling van de Nederlandse kleipijpennijverheid in de 17e en 18e eeuw.

Publication Year:

2019

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Description:

Critical book review of the thesis of R.D. Stam, Utrecht University, 2019 on the Dutch clay pipe industry.

As a museum curator, you are extremely curious when a dissertation in your field is published, especially knowing that it is the result of almost twenty years of research. That raises high expectations. It is also the first dissertation on the clay pipe to be defended in the Netherlands, after various promotions in Germany and England. In such a case, a size of 526 pages is by no means intimidating, but rather nourishing my reading appetite. Well, at first glance this thesis is exemplary because it has exactly the right form: research objective, method of elaboration, justification and conclusion, including a word of thanks (fig. 1). What is striking about the table of contents is that the set-up looks more like a docile school assignment, with an endless numerical paragraph division. Furthermore, an index is missing.

It must be stated that it is commendable to approach the subject of clay pipe from an economic perspective. No one has dared to do this so far and it certainly does not appear to be easy. Stam explains this in his first chapter. It is also certainly worth a compliment for someone who is over seventy, as is apparent from the PhD student's year of birth.

It goes without saying that the aim of the research (p. 19) and the research question (p. 19-22) are of primary importance. After reading these two paragraphs, with too many repetitions, you as a reader are left with an uneasy feeling. According to Stam, the aim of the research is: “to map the how and why of economic development, with special attention to exports” (p. 19). That why doesn't seem interesting to me in economic terms. A product is made and sold and the producer by definition strives for profit – that is his livelihood. The question of whereby would be more relevant, in other words: as a result of what. Then you will find out what the underlying economic and other factors are that make a company or industry successful. Later it appears that just this is Stam's intention, so why not immediately formulate the right question? Almost casually he states that the outline of the economic development of the pipe industry is not the goal (p. 19 ). It turns out that Stam spends more than 170 pages on this topic!

Completely unexpectedly one learns from the justification of the sources that the author excludes a primary part of his sources. It seems to me that writing economic history should be primarily conducting archival research, collecting data in order to build up a web of knowledge that is then the engine for scientific reasoning. Here it is stated very explicitly that no new archival research has been done (p. 24); according to Stam, that would yield too little.

The decision not to conduct archival research means to me that you miss many points of view. For example, by using the regulations and ordinances from publications, you do know the rules, but what has led to those regulations can be found in the pipe makers' demands and advice from guild administrators to the government. By reading it you get to know the atmosphere of the industry and you better understand underlying motives. It is precisely this insight that provides a more secure basis for interpretations. This educational process provides more nuance and deeper insights.

In addition, the researcher states that, in the absence of hard figures, the determination of the number of pipe makers and thus the production volume - an important point in his research - is based on estimates by previous authors (p. 22), from which averages are calculated, from which finally conclusions are drawn. He more or less apologizes that large parts of the research are therefore speculative. That sounds far from scientific.

I know that a great deal of literature on clay pipes, that is cited all over, is mainly produced by spare time researchers, amateurs for the most part, but this is all used in the research without weighing their significance. Sometimes you know of a writer that he was very young when the article appeared. In that respect you would expect a somewhat more critical selection. These factors create the risk that the foundation of the research is less solid than it appears.

Finally, Stam reports that the archaeological finds are usable to a limited extent, because the foreign finds are mainly available in drawings only. He rightly states that the determinations made abroad are often incorrect because Dutch specialist literature was not available or could not be read. For this reason, many finds have been re-identified and dated from the drawing by Stam. This so-called re-determination (p. 26, 320) creates a lot of noise on the line. On top of that, only later on in the book it will become clear that the number of finds is very small, for some countries only a handful of fragments. To be honest, Stam does list five reasons that invalidate the archaeological sources even further (p. 27-28). Again, the author is apparently not convinced that there is a solid foundation under the work. Stam coined the new term of re-determination as to explain the updating of obsolete identifications. At Stam, new insights are therefore derived from poorly legible drawings or unclear photos. That sounds fine, but is more a burlesque form of science. Stam himself states (p. 26): “To be able to give a proper identification, one has to hold every pipe in the hand”; something that any expert can confirm. Through ‘redetermination’, the sources are not weighted according to value, but reshaped into usable data. And sometimes, when it suits the argument, they are interpreted differently by not counting some of the material for the sake of the outcome (p. 353, 381).

Chapter 1 (50 pages) contains aspects necessary for a better understanding of what follows: the basic knowledge as an introduction into the matter. For me, the appreciation of this dissertation does not lie in this basic chapter. Here Stam shows that he has all possible literature, including grey literature, and that he has knowledge of all areas, even adjacent areas. However, it turns out to be a complete compilation of what has been written before, with the author citing too many details that are often irrelevant to the research. This detracts from scientific intentions.

As a reader, you lose the thread because the writing jumps from topic to topic, often looking in vain for a logic in the sequence. Many paragraphs contain a sentence at the end starting with “Ook” (Also) to add some additional information, without making it any clearer. An extensive section is, for example, about the introduction of tobacco in Europe. This is admittedly a run-up to the demand for pipes, but since it will then take at least forty years before the pipe industry becomes any size (Stam starts it in 1630, chapter 2), this introduction is hardly important. The same applies to the English pipe makers, who are presented with much ado, but soon no longer play a significant role in the argument.

Halfway through chapter 1, between the enumeration of the professional literature and the production method of the clay pipe, there is a sudden jump to economic theories (p. 35-39). Since these are not introduced, no one wonders what the relation with the subject of the chapter is, although they do create an expectation.

Furthermore, especially in that first chapter, the language is not flexible, so that it seems that the author doesn’t completely master the material. A nice sentence as an example is: “In the local and regional centres the development of the shape of the Gouda pipe was followed, albeit sometimes a little later and sometimes at some distance, as in Maastricht” (p. 48) evokes more confusion than facts. And a second: “In the Netherlands moulds have always been used to shape the pipes, but moulds with a groove for cutting the top have never been used in our country” (p. 56). Besides being false, the sentence is evidently a linguistic flop.

May I mention a few points by way of illustration? Technology transfer (in this case: from England to our country) is a wonderful economic concept, but in the pipe industry it appears to be hardly the case (p. 56-57). Stam comes up with one example of an English shaped kiln on Dutch soil, but easily lists six or seven points that indicate independent technical development. So there is a negative outcome in terms of technology transfer. To your surprise, you do not read that conclusion. It remains unclear why an entire paragraph is devoted to this unique example. It seems that this title was taken from the first German dissertation on clay pipes where this term is used as a chapter title. Wouldn't it have been much more informative here to focus on the evolution in technology in Gouda and contrast it with what I would call the cottage industry in England? No transfer but crystal clear the differences between the two industries. Then it would have become very clear what special merits the Gouda pipe makers had and how the product there reached the highest imaginable level.

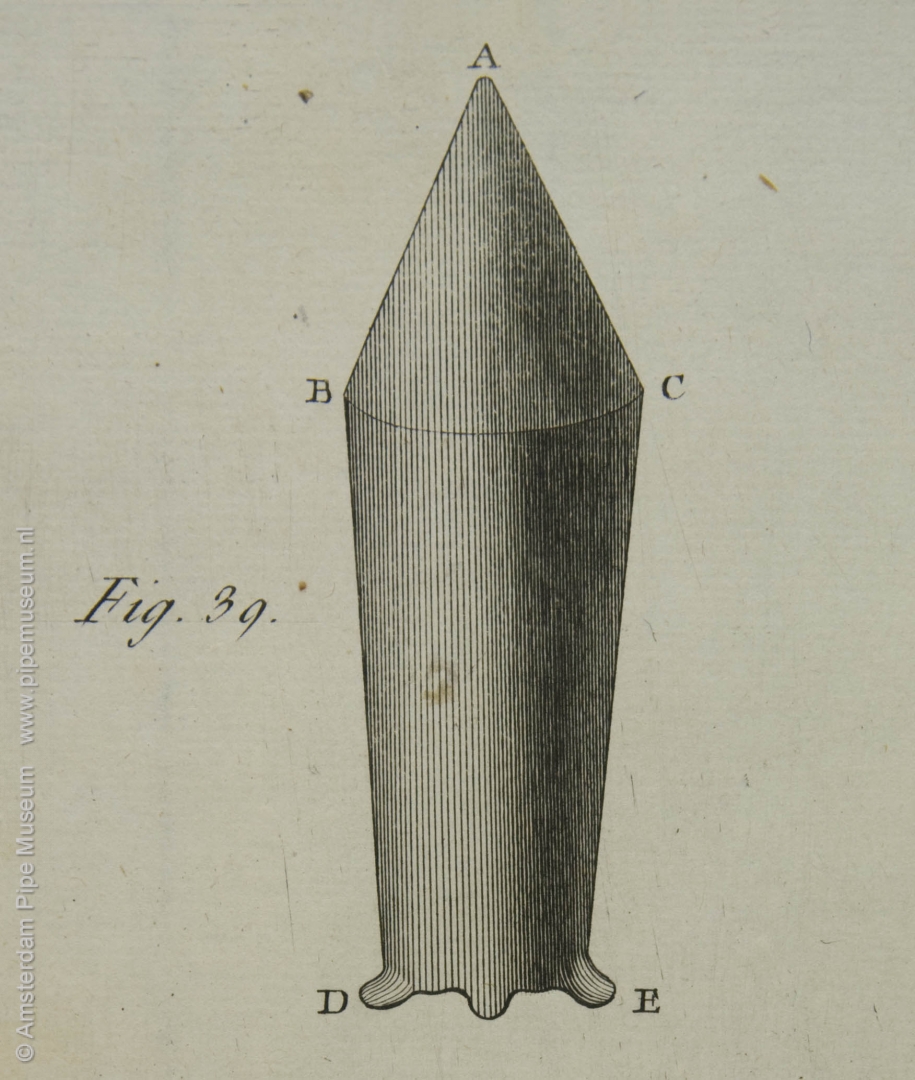

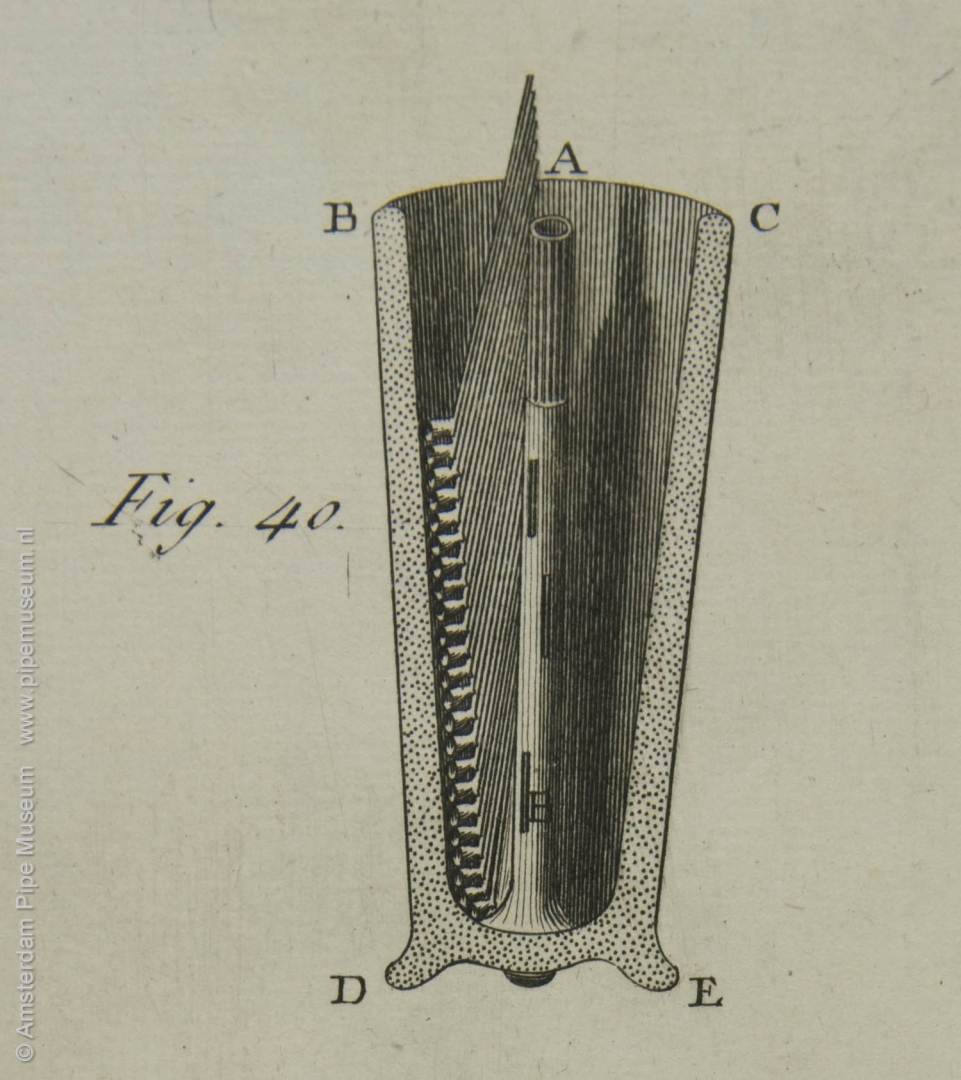

Accents in technology are also laid differently than you would expect. For example, a wooden pipe mould found in London (p. 56), the agate stone (p. 43) and the pipe pot lid (p. 44-45) are discussed in detail, while other more unique aspects for Gouda remain almost unmentioned. For example, how the use of the trumpet and the scrubbing (p. 44) actually works as the most important secret of the Gouda industry (fig. 2). The only plausible explanation for Stam's digressions here is that specific articles he wants to refer to were written by himself or by his closest friends. This kind of obvious display of knowledge cannot be the intention of a dissertation.

The shape development or typology of the clay pipe is not presented very clearly (p. 47-48). The word basic shape, a concept I introduced in 1987, has been renounced, but nothing distinctive has replaced it. Although the development of the pipe shape is discussed step by step, it is just as diffuse as the treatment of the first generation pipe (that word is retained in this work). Also showing the chronology upside down (p. 47, figs. 1.3.1 and 1.3.3) creates confusion rather than clarifies. Why, by the way, the earliest clay pipe (§ 1.1.4.2.) is treated in a later section than the rest of the shapes (§ 1.1.3.) is a total mystery to me.

My own hobbyhorse, the phenomenon of the pipe makers’ assortment remains completely out of the picture. When selling, whether it is locally, regionally or at an export level, it is very important to identify which customer group the pipe factory has focused on and from which range a certain segment of the production has been selected. That says a lot about the fashion in the destination region. Stam distinguishes significantly fewer types of pipes than reality offered. In addition to the variation in a few types of coarse pipes, of which the pipes with embossed side mark gets too much attention, he talks about the so-called 'long quality pipes', a concept that implies much more than is suggested. That name doesn’t give credits to the great merit of the Gouda so-called oversized pipe, the above-long quality pipe that does not appear in the book, with the exception as a side note in a price list (p. 365). It is precisely this type of pipe that has mainly been an export item: in the eighteenth century, wealthy Polish women, for example, were fond of these over-sized pipes (fig. 3). It is no coincidence that the reported list refers to the prices of the oversized pipes in Poland. But, of course, it's all about the main text, laid out in chapters 2 to 4.

Chapter 2 (176 pages) gives the detailed economic development of the pipe industry in the Seven Provinces, with logical emphasis on Gouda. Why then does the story begin with smoking and the tobacco polemic (§ 2.2.1.2), that would have been the logic step after the beginning of smoking in chapter 1 (§ 1.1.4.1). Even chewing tobacco, snuff and the cigar (§ 2.2.1.3) including pipes of other materials well into the nineteenth century (§ 2.2.1.4) are themes that may be useful as basic knowledge (Chapter 1), but do not contribute to the outline of clay pipe production in our country. The argument goes on for 176 pages with many deviations from the subject and countless repetitions, which does not encourage reading. It is certainly a pity that a good final editing has been lacking, as a result of which lots of inconsistencies in the punctuation remained, as well as disturbing repetitions and in-between sentences that are irrelevant in the argument.

Really annoying when reading is the profusely used word centre, in this context meaning a production site for clay pipes or an ordinary city or village. This appears to be a choice of Stam as a self-invented definition (p. 141, note 373) to avoid the word village. In § 2.2.5 alone (about the pipe production outside Gouda) this yields the word centre 42 times, while none of these towns qualifies as a centre of production, rather the location of an individual maker.

It is remarkable that such an extensive discourse still raises so many obvious questions, questions to which there is no answer to be found. For example, it is interesting to read what, according to Stam, the preconditions are for a city to successfully develop into a centre of pipe production. That is a) serious tobacco consumption, b) an infrastructure of waterways and c) the presence of potters kilns. Point a) is a chicken-and-egg discussion. Does pipe production follow tobacco consumption or is it the other way around: is smoking stimulated by the availability of a wide range of pipes? You would expect in a scientific work a comparison of cities that also meet these preconditions, or of which it can be assumed, in order to verify the hypothesis. Amsterdam or Gouda could be compared with cities such as Hamburg, Cologne, Koblenz or Rouen.

Other conclusions are so logical that it is questionable whether Stam's substantiation has much to add. In § 2.2.4 dealing with trade relations, he states that successful trade takes place on the basis of personal and even family contacts (p. 137). He proves this, among other things, with finds of pipes by well-known pipe makers far from home, but does not provide any insight into the company nor the personal living circumstances of these producers. It is precisely these data that will provide a picture of the importance of the company within the network of social contacts, from which the commercial contacts can be explained. Merely based on archaeological finds is in this case no convincing evidence.

An extremely interesting theme is dealt with in § 2.2.9: an estimate of the volume of pipe production in Gouda (p. 182-203). Stam provides an extensive and as such useful overview of all secondary sources from two centuries of Gouda historiography. All these examples have their drawbacks. Based on mere estimates and assumptions, he starts making calculations of the numbers of employees in the pipe industry and the assumed production numbers. Despite all the warnings that these are assumptions, he keeps on calculating. Those 20 pages give the impression of a solid scientific work, but the accumulation of estimated data makes the end result fully questionable. In addition to the reservations that Stam has already expressed, one can easily add a number of reasons that make the figures unreliable. Do small bosses work every day in their workshop or are they also on the market for a day a week to sell their product? That differs in weekly production, with huge effect per year. Very often pipemakers' bosses, who were entitled to own a workshop, are employed by large companies so they no longer produce in their own name. How can you ensure that their production is not counted twice? Since there are no unambiguous data from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, nobody can improve nor falsify the figures that Stam calculates, so that he has created a kind of pseudo-truth. Science or attention seeking? I do not know. One thing is certain, the figures cannot be correct, because physically there is simply insufficient baking capacity available in Gouda for the production figures set by him. The production must therefore have been many tens of percent lower! With the (estimated) numbers of pipe makers as a starting point, the size of the contributing occupations is estimated far too high. This creates an impression of a predominant capital industry, but the truth has been seriously violated.

At the end of chapter 2 it gets even more surprising. After 11 pages (§ 2.2.12) Stam himself comes to the disconcerting conclusion that the theoretical models of Porter, Levitt and Vernon, introduced so expectantly in chapter 1, do not apply to the pipe industry! That means that beautiful models, schemes and pages full of theorized haggling have no function other than page filling. Humbug!

Chapters 3 and 4 (102 and 43 pages, respectively) contain very intriguing paragraphs in which historical data are linked with archaeological finds, although the whole is heavily based on Duco 2003 and Van Oostveen/Stam 2011. In a previous book review I extensively pointed out that the latter book is largely taken from a study by Duco already published in Oxford in 1981. The extra-European trade and the role of the VOC and WIC in particular are worth reading and innovative, although, in view of the notes, this piece goes back to research by Van der Lingen. It is not surprising that his work is a key witness, since Van der Lingen did carry out lengthy archival research in contrast with Stam. Stam has clearly been able to find the most (published) data about the export to Germany, significantly less about Belgium and France, for example, which makes them a poor in result. Which doesn’t mean that the export to the south was not important for Gouda. It says something about the published information and shows once again that primary source research is a must. That alone provides historical accuracy.

Chapter 4 talks about the same areas, but using archaeological finds and now it's getting really questionable. The published finds of clay pipes from abroad appear to be very irregularly distributed across Europe, let alone the rest of the world. The chapter is largely dependent on archaeological research and appears to be the work of a handful of amateur archaeologists, mostly acquaintances of Stam. A wish of Stam (§ 4.4.6) is to determine which pipe makers were important in the export. The inability to trace certain brands of Gouda pipes is enough proof for Stam to declare that some of the well-known makers in Gouda are by consequence not that important. However, without including domestic trade in the investigation, this is definitely premature. The importance of a pipe maker depends on his total sales, both domestic and foreign.

When the Amsterdam pipe maker Edward Bird is mentioned, in addition to the gigantic export to New Netherland, his export to Sweden is always added. After countless mentions (p. 82, 84, 89, 204, 294, 310, 317, 352, 399) such an addition becomes annoying, isn't it more about interpretive views? Colleague Åkerhagen did put the pipe finds from Sweden on the map, which is why Sweden is better documented than many other countries. Finding Birds’ pipes among them now awards him this second export country. Whether there are no more export areas for Bird is not even suggested as a possibility. Findings do indicate this (fig. 4). For Poland, the inventory of the pipe finds was done by a few serious collectors and therefore that country is also better represented. Data is missing from many other sites, but that does not mean that the export has been less.

The same problem of using sources selectively is reflected in a most curious internal incongruity in this book. If you go through the 45 pages of appendices, you will find on page 464 a table with export data from the eighteenth century, already published in 1915. It concerns the export of pipes from Amsterdam, expressed in guilders. It is not so much the value as the relationships between the export areas that are interesting. Let us take the year 1753 as an example. The export to Germany is then 2800 plus 1850 for navigation over the Rhine and no less than 25,000 to Hamburg, Bremen and Kleine Oost (Small East), or a total of 29,650 guilders. We must bear in mind that Hamburg was the transhipment or transit port for all trade to the Baltic Sea region: Prussia, especially Poland, but also the Baltic States and even Russia. For the Netherlands, trade in this area, the so-called Mother Trade, was by far the largest in size already for centuries, so because of the vast network it was logical that pipes also went there. In the first place, given the large number of pipe finds in Prussia and Poland, a considerable part of the 25,000 guilders in pipes must have been intended for this area, if not the whole amount refers to the Kleine Oost. That leaves no more than 5,000 to 15,000 guilders for Germany itself. In the same year, more than 7,000 guilders on pipes is exported to France, a maximum of half that of Germany, but certainly considerable. The export over the Rhine and the rest of Germany is together 4,650 guilders or 65% of France! How can this be reconciled with Stam's statement in § 3.3.1.3.2 (p. 267-269): "That France has never become such an important import country for Dutch pipes as, for example, Germany". Finally the researcher does have hard contemporary figures for export and then he ignores the figures of France as an export country without any explanation. Is that perhaps because it is not useful in his argument, which is, after all, built up from data that he was able to find in secondary literature and which, as he claims, are very poor from France?

It becomes even more extreme when Denmark is mentioned (together with Sweden and Norway): almost 20,000 guilders. If we look at Denmark in the main text, this country does not even appear in Stams’ table of contents, but must be searched under other countries (§ 3.3.1.4, p. 274). In addition to high imposts on imported pipes and even an import ban, Stam cites a one-off import of 40 gross of pipes, coincidentally in the same year 1753, as a reason for not considering Scandinavia to be of any importance. However, this is incompatible with an export worth 20,000 guilders, which Stam prefers to conceal. The table in 1791 shows that this was not an exceptional year with large sales: even then the export from Amsterdam was still 17,500 guilders, so comparable to 1753. In that same year 1791, Germany again achieved 17,800 guilders including the Baltic Sea and was therefore barely more important. Without a note to justify, Stam casually mentions in his text that 50% of the pipes in Danish excavations are Dutch (p. 275), which is logical given the size of the export according to the table. Furthermore the importance of exports to Denmark is proven with pipes designed specifically for that market segment (fig. 5), overlooked by Stam. Stam's very succinct text about Denmark in any case contradicts reality. Incidentally, it should be noted that Denmark very oddly is threated after Norway and before Iceland, both Danish territories in the eighteenth century.

Much attention is paid to the major pipe brands, they are made the basis of the calculation model with which the elite from the Gouda industry is identified and linked with sales outside our national borders at the time. Differentiating between large and small companies and determining what the economic cork of a particular company has been is an interesting challenge. Stam sets the criteria for this, but again purely from the accessible secondary sources; he very effectively calls it the assessment framework (p. 379). Calculating and plotting figures in a graph or model does not guarantee a scientifically correct outcome, although the methodology may well be. With too few finds and poor identifications you can hardly get on with it. Yet it is a miracle that all this calculation shows a plausible distribution pattern, although we will never know to what level this is rooted in reality.

An interesting challenge is marking the heyday of the brands. This requires a purely archival study because the prosperity of a brand is primarily related to the efforts of the maker, which in turn is linked to his own stage of life. Is it a young energetic entrepreneur or an elderly person? This very personal situation influences the output and thus the sales, to whatever market. In light of that, all brands have their own heyday that is an exciting interplay between the macro and micro-economy. The specific features of the macro-economy, or the pipe industry viewed from a great distance, indicate the main features, the various companies are active within this framework, though the importance of the brand depends on the personal situation. Marking the heyday of the individual brands is a mega puzzle in details, fun for collectors, but science prefers to limit itself to the main points, where the extremes should not go unmentioned.

The juggling with numbers processed into graphs looks interesting and also gives the impression of higher science. As already indicated, the figures are not as reliable as you would like, so that all those graphs have to be seriously questioned. Stam does that himself, first of all by stating this in the justification and also in the text by interspersing everything with presumably (288x), probably (110x), it may be assumed that (23x), presumed (24x), estimate (35x), plausible (31x) and especially the word possible (343x) or together 854 doubts. The limited number of contemporary sources in which numbers are mentioned, the marginal foreign finds in relation to the assumed export, the unusable determinations in foreign publications in particular, all grounds for doubt have already been mentioned. However, this does not stop Stam from continuing on the chosen path.

Are there really no sources that could provide more solid insight? Yes, of course. The Gouda archives contain a large number of inventories of pipe makers. In the event of death or bankruptcy, a detailed statement of all assets is often drawn up, in which the debts and assets still to be collected are particularly interesting. Then it turns out that large pipe makers, for example, maintain a “Zeeland debt book” with credits on Zeeland traders for supplied pipes. You will also come across simple lists of debts. In other cases, there is a record stating many tens of thousands of pipes in stock in a warehouse, broken down by type. But if the researcher rejects going to an archive as a research method in advance, then these sources are left behind.

As a matter of fact, the greatest certainty about the size of the pipe makers workshop is the number of vices, not the moulds. They are directly related to the number of ’casters’ (men who produce the clay pipe out of the mould), which in turn is crucial to the calculation of the production numbers. Quite a lot of examples of this are known from Gouda from estate inventories. More specific sources are the shipments of several large pipe exporters in the Goudse chamber books (p. 212) and also an interesting ledger by Verzijl (p. 211), known since 1999. These last two sources are mentioned but not elaborated upon. All in all, these archival documents still contain a wealth of valid information, which can clarify the dubious picture that Stam paints.

The same could be true of recent archaeological literature. Following the implementation of the Malta Convention, the ADC has issued a huge number of find reports across the Netherlands, many of which contain useful information about clay pipes. Although they are about the Netherlands, the pipe makers really looked first and foremost for sales in the vicinity of their location and therefore ended up in the Dutch provinces before they focused their sales abroad. For more foreign finds, use could be made of the well-developed databases that can be found on the Internet, for example the Canadian Archaeological Service (archeolab.quebec). The pipe finds in Recife, the capital of the Dutch settlement in Brazil, have been published quite extensively, but I can't find anything back in Stam. These are just a few, rather random examples of untapped opportunities for additional archaeological resources.

Other finds can be found at numerous larger museums holding interesting archaeological collections that provide insight into the finds in a particular region. In the eighties, for example, I learned immensely about the export of Gouda pipes in the depot collection in the National Museum in Copenhagen. Many other city museums and archaeological services manage such finds. One must bear in mind that every find is useful because it is about the frequency of occurrence, not about the coherence of the finds or a special stratigraphy. In addition, the online database of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum contains more than 8,000 archaeological finds, including find sites, of which 6,321 fall within the period studied (fig. 6). This has not been considered either. Stamps on the pipe stem with makers names are another important way to determine the importance of makers. That opportunity was also missed.

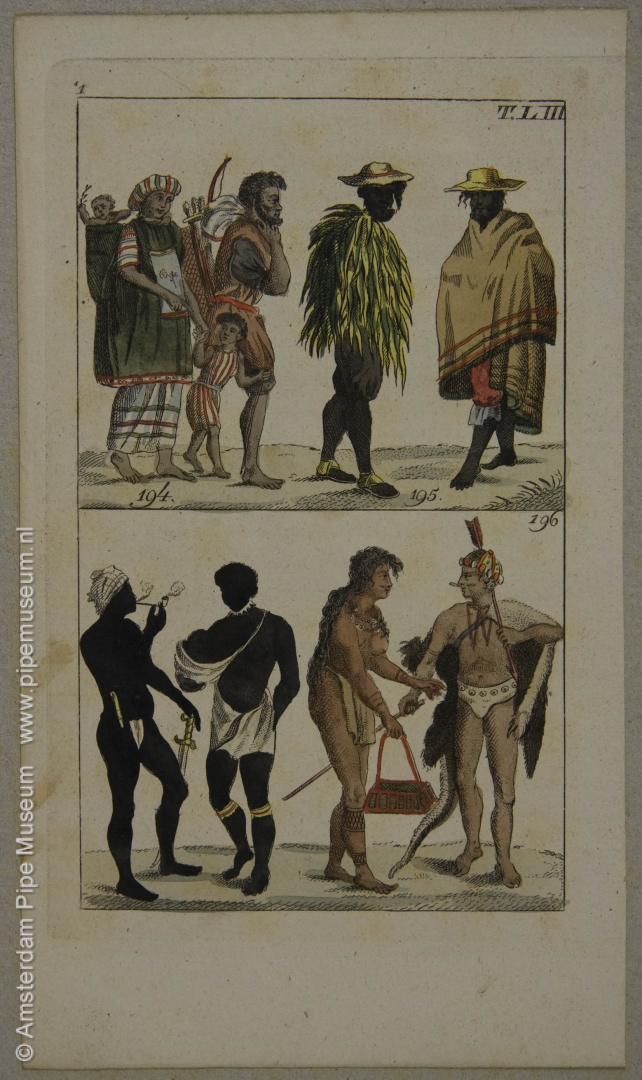

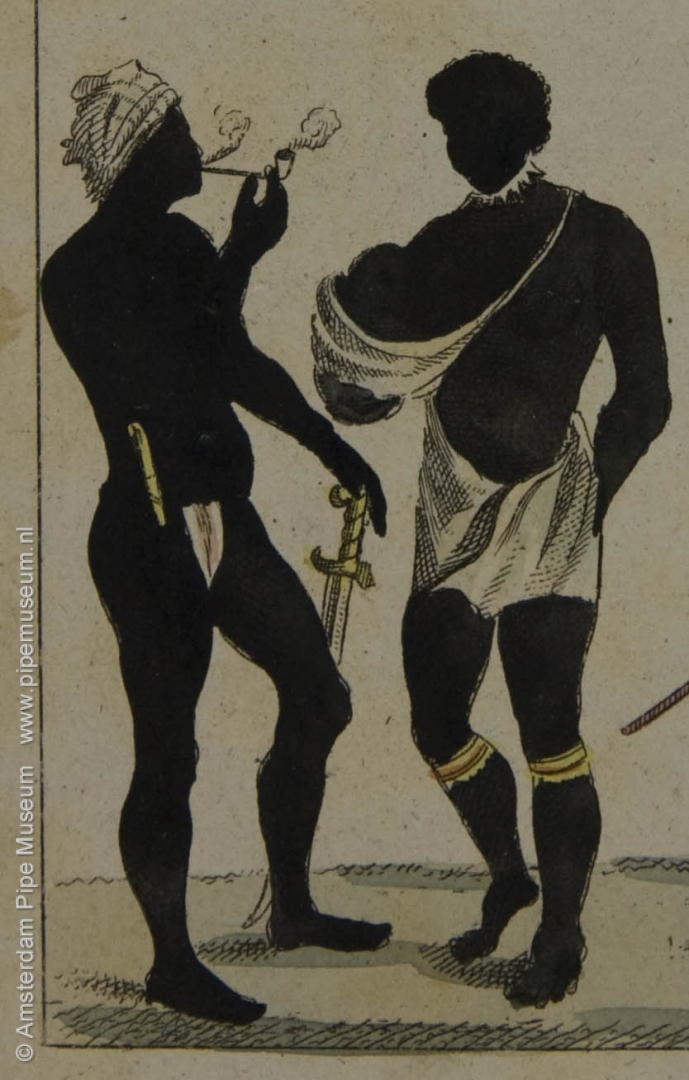

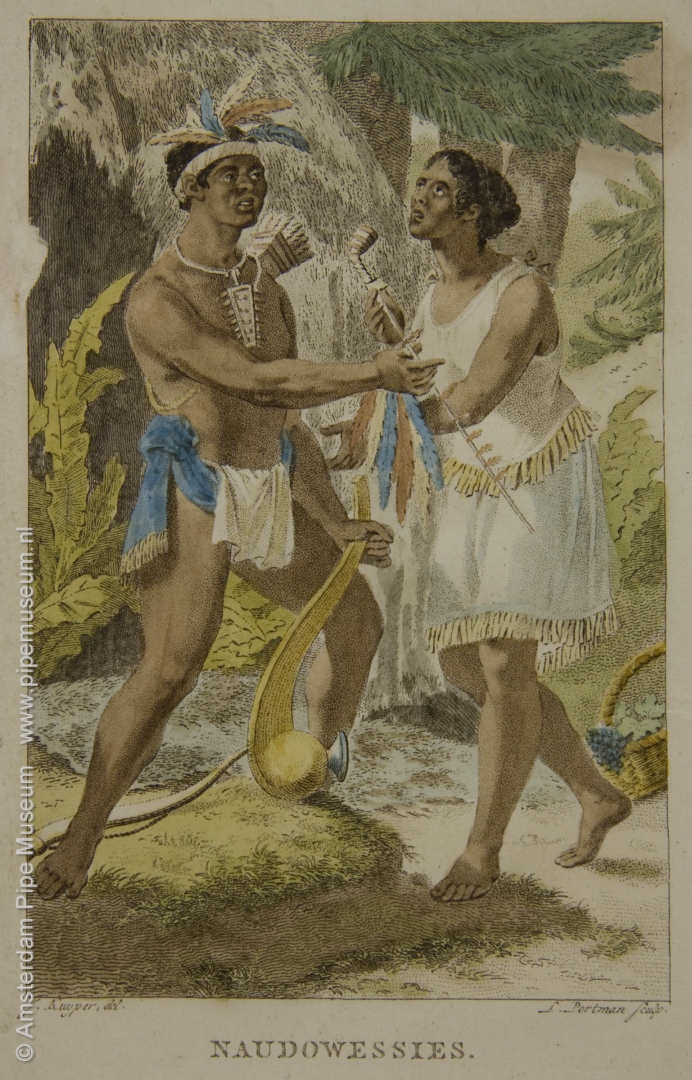

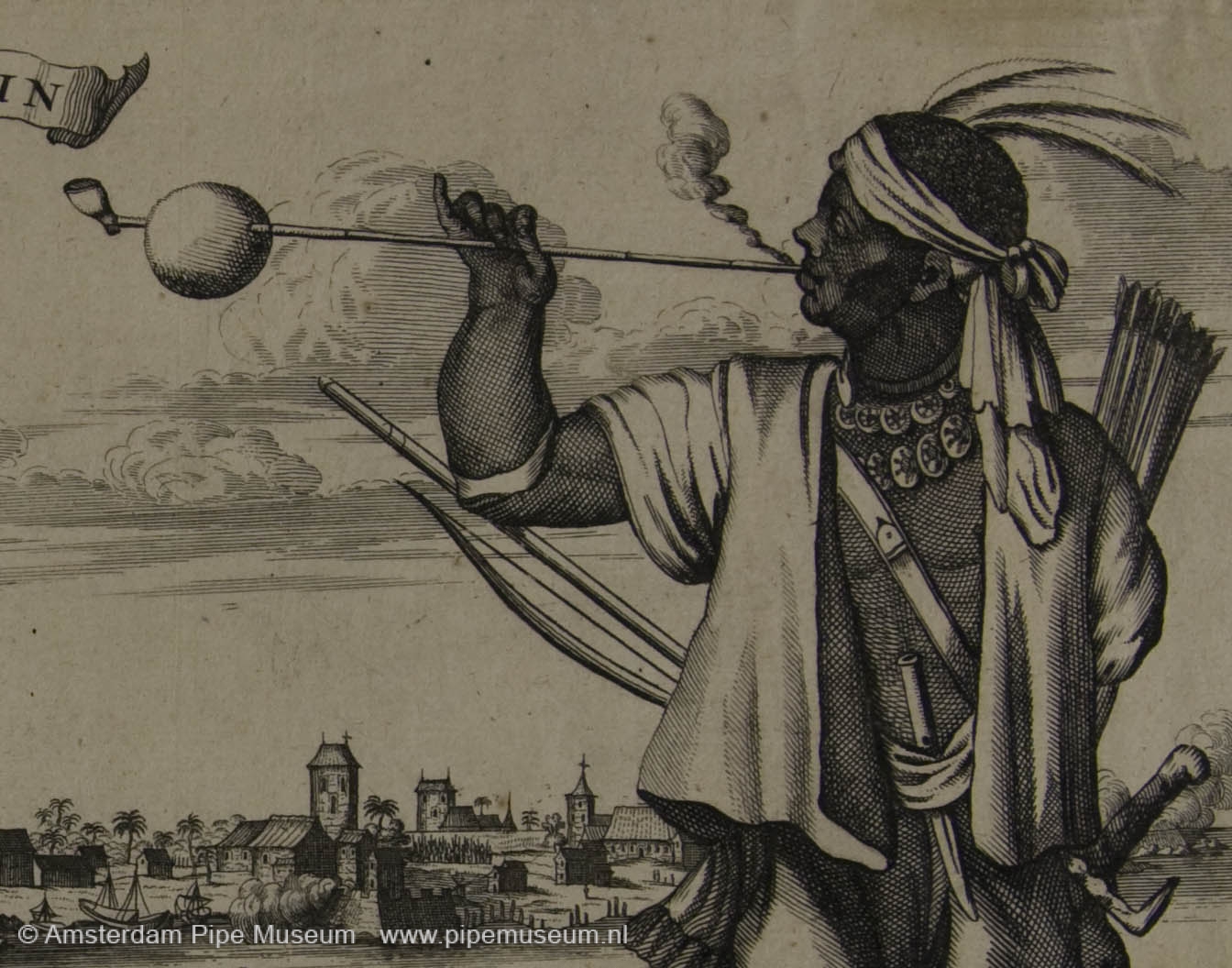

Finally something about the images. Clay pipes are not really photogenic. The strength of the Gouda quality pipe lies in its balanced shape and fragile appearance; that is why the clay pipe arouses admiration when you see and touch it in its full shine. As an archaeological pipe bowl, however, it has become a boring object, especially when it is depicted in two dimensions, and that is a given in publications. Would it not have been better to show a few complete pipes between the images of the pipe bowls, so that the balance in the Gouda quality pipe is shown to its full extend? It is precisely this special product balance – perfectly symmetrical bowl, long straight delicate stem, connected with a modest but yet pronounced heel - that is the reason why the successful export has started. Six depictions of smokers (p. 7, 69, 70, 76, 113 and 180) present the user function of the pipe, but are insufficient to present the image of use and appreciation properly. Moreover, they are not anchored in the text. Pictures of smokers from abroad would also have been a nice illustration of the export, including the mention of who smoked from which pipe (fig. 7-9). Admittedly, an art historian has a different approach than simply presenting the historical line.

Chapter 5 (25 pages) announces the conclusion, but is rather a summary of the book, because there are too many details that should be left in the main text. It is a pity that this chapter contains hardly any references to the main text, so that you can go back to read a further explanation or substantiation if you wish. Stam does that in completely random places, but sometimes you end up completely wrong (p. 414). The summary presents the reader with the same problem as with the main text: you can’t get a grip on the story. You read a lot of facts and details, but it does not come to a coherent unity. Specific dates and figures are also omitted in the conclusion, this could have helped the reader to hold on to known milestones in history. There doesn't seem to be a real conclusion either, it remains obscure what Stam has discovered with his lengthy research. Or is this Stam's thesis that a specific peak of the Gouda pipe industry can be identified: the year 1737 (p. 406). This has never been done before and he put it as a contrast with previous literature. But… then you read (p. 408) that he himself contradicts his evidence for this: the peak of the design and quality lies in the years 1740-1750.

In any case, one thing is somewhat innovative. Stam associates the stagnation and decline of industry with a multitude of largely economic factors: import duties and tolls abroad, competition from abroad, the general decline in living standards, imposts on peat. Although Dirk Goedewaagen already stated this in the 1940s, Stam explains exactly how this all interacted. It is a pity that in the next section (§ 5.5.6) these trade barriers are discussed again and are repeated in detail. That is already disturbing for a summary, but absolutely not done in a conclusion. Incidentally, it turns out that those obstacles did play a role in German areas, but not in Belgium, France and the whole of Scandinavia. So the truth is really more multidimensional.

By deduction we may say that you cannot speak of a conclusion in the thesis, so that the dissertation remains more of a sketch of a Dutch industry with a focus on export. Many of the examples mentioned here of strange order, division of information over different chapters and contradictions within the book, indicate that the researcher is not above the matter. This is also in line with the lament of Stam himself in his word of thanks (p. 524): “… I thought that I should display the discipline of writing a dissertation (after all my spare time studies)”. It is clear that Stam has done a lot of work, had extensive conversations with many fellow collectors, collected an enormous amount of professional literature and then fiddled with all the data. Of course, this dissertation offers new ideas, but they are hidden in a mass of text that is hard to digest with, as noted, too many repetitions. Despite all this diligent work, on the other hand, it must be noted that it doesn’t give credit to the pipe industry. Again, my opinion is that the domestic trade for a product such as the clay pipe cannot be disregarded, in doing so one provides an incomplete and therefore skewed picture. So instead of taking two centuries, it would have been better to take just one century and view it from a domestic and foreign perspective. If the pipe export had also been divided into logical segments – nearby markets such as France and Germany, against the Baltic region, the VOC and WIC trade – then a clear picture would have emerged. Now we have to do with dozens of pin pricks of accidental finds abroad that cannot provide a complete overview.

I would rather have seen in the conclusion only insight into the (economic) process of change per period. This may or may not be in a comparative manner across the various centres or as a common thread through time with regard to production and sales. Of course, all of this explained in relation to the economy of that moment. Here it would also have been appropriate to apply economic theories to the results for a better embedding in Dutch and foreign economic history. Porter, who is already introduced in Chapter 1 (pp. 35-39), has ultimately not been given much function in this argument. There are some nice hypotheses attached to Levitt's thinking. The flywheel that drives industry is such an appropriate invention (p. 235), but economic schematization of decay calls for another illustrative model in which cause and effect become visible. That's missing. Finally, for me as an art historian, the part on the Jonah pipes (p. 236-239) is devoid of any insight into the evolution of the clay pipe by applying a theory.

The question remains whether the book is intended solely as a dissertation, as a test for the PhD student to show that he can work at the highest possible scientific level. Rather, it seems that the author intended to write a book in which the complete industry is treated. Whether that can be done without consulting primary sources is something I highly doubt. If the author seeks to captivate with his book the average pipe researcher - as we saw often an interested amateur - a more transparent work is desired. Such person needs a readable book and unfortunately this isn’t. Reading through the entire 420-page book (up to the English summary and appendices) is already such a task due to the incoherent and poorly edited text. Then you have a kind of picture of the industry, but no certainty about what you have read because Stam himself surrounds everything with so many question marks, spreading probably and presumably. Hopefully in the future there will be diligent students who want to delve into a specific aspect or export channel from which new conclusions can be drawn after studying better sources with more authority.

© Don Duco, Amsterdam Pipe Museum, 2019.

Pictures

- Cover thesis R.D. Stam

Amsterdam Pipe Museum, library - Cut-out with the pipe pot and trumpet from Diderot's encyclopaedia. Paris, Diderot & D'Alembert, 1771-1785.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.532b - Print of a seated pipe smoker with an oversized clay pipe. Paris, Johann Georg Will, 1741.

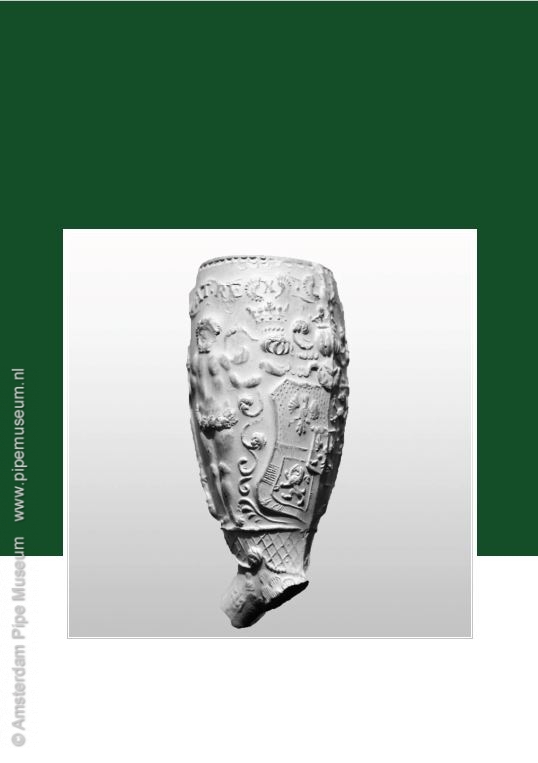

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.130 - Tobacco pipe for export with an image of King Charles II of Spain and the royal coat of arms. Gouda, Adriaan van der Cruis, 1675-1690, heel mark EB.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 12.985 - Pipe bowl with curved bowl on which the coat of arms of Denmark. Gouda, 1735-1750.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.521 - So-called kasjotte, export pipe. Gouda, Pieter Stomman in the name of Geertruij Stomman, 1780-1820.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 7.883d - Print of a smoking Blackman with a kasjotte Germany, 1750-1810.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.141 - Print with two Indians, the woman offers the man a long-stemmed pipe. Netherlands, Jacques Kuijper, 1802-1807.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.219 - Print of clay pipe smoker with added cooling reservoir for the gate of Coichin, India (Cochin, now Kochi). Amsterdam, A. Meijer, 1690-1695.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.261