Highlights of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Hoogtepunten uit het Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Année de publication:

2020

Éditeur:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

The agate stone as a quality symbol

Few tools have a baffling aesthetic value. Logical because they are not made as an ornament, but as a means for production. This agate stone is an exception to this rule. It was used in Gouda to smooth the clay pipes. The so-called geglaasde pijpen, stroke burnished pipes had already been invented by the first generation of pipe makers dating back to before 1600. In Gouda, this use developed to the highest level. The agate stone became the symbol of the most beautiful and expensive pipes, the so-called porceleyne, porcelain quality.

The stroke burnishing was done by women, who were usually older, because the burnishing was not a heavy job but a task that had to be done very cautiously. These so-called glaasters stroke with the agate pin along the leather dry clay and forced the clay plates in one direction. After the pipe was baked, a beautiful shine was obtained. For the best specimen that shine was enhanced by rubbing the product with some white wax.

In the pipe making workshop the agate stones were issued to the female workers by name. A glaaster signed for receipt and the manufacturer knew exactly how many stones were in circulation at his workshop. The purchase price was high, they were the most expensive piece of hand tools. The care for the stones was therefore well-founded. Rumour has it that the tools were called glaassteen, literally glass stone, in order to keep the employees in the dark about the preciousness of the stone.

What makes the tool shown here so special is the beautiful layering that is at right angles to the stone and thus shows an attractive pattern of stripes. Furthermore, the handle is striking, not turned out of the usual wood but out of bone. Usually murky stones are used, ultimately it was about the use and not about the beauty. The handles were made of ordinary roughly finished wood. With the help of a brass or iron ferrule, the stone was attached to the handle. What has inspired the maker to deviate from this custom and to make such a luxurious tool is still the question.

Due to its careful execution, this tool certainly gives the impression that it is intended to be exhibited. That is very possible. From the beginning of the nineteenth century the Gouda pipe makers exhibited at national and even international exhibitions. In addition to their product, the tools were also displayed to show visitors how the manufacture of pipes worked. This stone could very well be made for such a presentation. The fact that the wear and tear is minimal might be a sign in this direction.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 5.261

The mark panel of the Gouda pipe makers

From 1660 onwards, the Gouda pipe makers were united in a guild. This guild stimulates the economic possibilities of its members and the result is that the Gouda pipe industry is growing tremendously. With the increase in the number of independent bosses, the number of pipe marks is also increasing. For the guild it is becoming more and more difficult to register it. It is not surprising that the board decides to make a mark card, on which all marks are depicted.

This card is not a paper or cardboard administration but a wooden panel on which the marks are painted. That panel soon becomes the symbol of the mark protection that the guild tried to guarantee. The servant of the guild would be able to visit the workplaces with the board in hand if there was reason to believe that a certain boss did not follow the correct use of the mark. At meetings, it also served as proof of supposed similarity of brands or other service in disputes.

When the guild continues to grow in size, a much larger mark board comes into use next to this carrier board, which decorated the walls of the guild room. A clearer painting was then made of the pipe brands in use. Figure marks, letter marks and number marks each get their own section. From that moment on, it was also customary to paint over the banned trademarks and those that had fallen out of use. That never happened with this carrier board. Occasionally, however, a brand has been removed and replaced by another. We do not know how long this sign has been in use. It probably fell into disuse as early as the eighteenth century.

In 1908 the guild records and insignia of the Gouda pipe makers were handed over to the municipality of Gouda, this mark panel was not there. According to say it had been left at a meeting during a quarrel and was taken home by one of the manufacturers. That was in a period when people did not take it too seriously with the historical material of the pipe makers guild. Eventually the panel came in the possession of Pieter Jacobus van der Want, a manufacturer and director of one of the oldest companies, having a serious interest in the history of the pipe industry. For years, this sign hung over the canapé at the family's home, next to a pamphlet about alcohol abuse, another toppic of the manufacturer. The next generation was less committed to history and stored it in a cabinet. So it survived the time until it was given on loan at the opening of the Museum De Moriaan in Gouda. That was in 1938. In 1953 this sign was retrieved. The manufacturer did not agree with the one-sided presentation in the museum of the Gouda pipe industry and he was right.

The sign would no longer return to Gouda. Not long after the appearance of the standard work on the Gouda marks by Don Duco, the mark panel was granted to the Amsterdam Pipe Museum. Since then, it has been a permanent exhibit as a symbol of the long-lasting endeavour of the Gouda pipe makers for mark protection, but also as an silent opposition to the lack of interest shown by the Gouda museums for their local pipe history.

Literature: D.H. Duco, Merken en merkenrecht van de pijpenmakers in Gouda (The pipe-makers in Gouda, their marks and ordinances), Amsterdam, 2003.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.424

Printing block of allure

In the eighteenth century it was fashionable among the Gouda pipe makers when bringing their pipes on the market, to provide these with a brand paper or velletje. These long and narrow paper sheets were printed with a central mark of the manufacturer usually in an appropriate frame. The brand paper was glued around the baskets or barrels with pipes and served as a seal for the merchandise. It was also custom to write an address on it when the pipes were shipped.

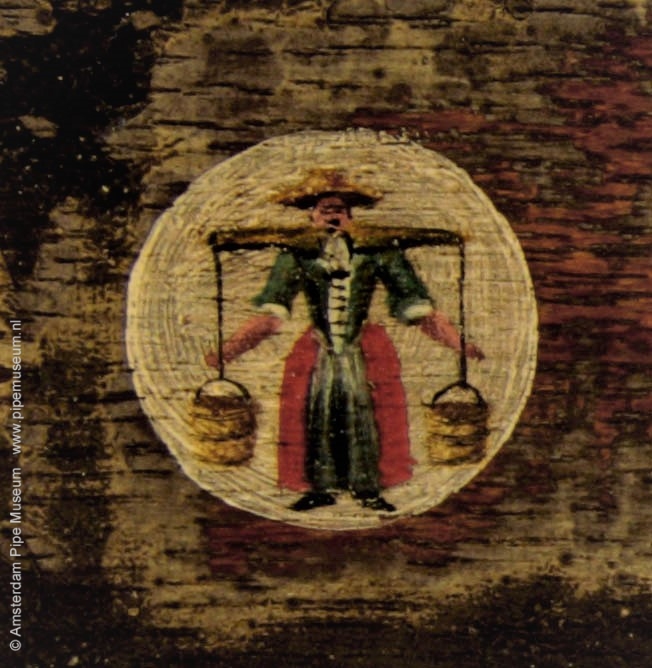

Already in the first half of the eighteenth century, beautiful mark frames were created with the name of the supplier, the arms of Gouda flanked by bunches of clay pipes and additional ornaments. Most pipe makers used a standard mark vignette. A very appropriate example of exceptional design is the printing block shown here: two pipe carriers walking with a barrel and a basket filled with pipes between poles on a cobbled street, accompanied by a jumping dog. It is a daily scene from life in the city of Gouda, when there were still around four hundred independent pipe maker workshops. Above the scene, an oval shield holds the pipe maker mark crowned A, surrounded by a ribbon with the maker's name. On top of all this we see the Gouda coat of arms, flanked by bundles of clay pipes and the text "PER ASPERA ADASTRA". A wavy text ribbon reads "OPREGTE GOUDZE PYPE VAN DE GEKR. A" (genuine Gouda pipes marked crowned A).

This elaborate printing plate is made of rolled brass, in which first the contours of the image have been cut out. Then the scene and texts were carved out with the burin very accurately with steady hand. That must have been done between 1735 and 1745. Engraver is Dillis van Oyen, at that moment the most gifted silversmith in Gouda. Incidentally, the image is not a conception of that moment but this was taken from the silver funeral shields that the Gouda pipe makers had orderd at a Rotterdam silversmith a few years earlier.

Such a merkplaat (brand printing plate) as it was named were rather expensive. They symbolized the commercial value of the pipe mark and the engraving was not cheap at all. That is why most smaller manufacturers used a printing block of wood. Not surprising, therefore, that if the brand was transferred to a new owner, the plate was sold with it and the text was adjusted. That has happened here as well, even several times. In the end, the entire mark insert was replaced with copper. That change was executed between 1795 and 1820 when the last owner Cornelis Brem started to use this printing plate. This mark printing plate is not the only one that stayed in use over a period of almost a century. The Gouda pipe industry was thoroughly traditional and many habits continued for generations, surprisingly enough also those of the advertisement of the pipe mark.

Literature: D.H. Duco, Merken en merkenrecht van de pijpenmakers in Gouda (The pipe-makers in Gouda, their marks and ordinances), Amsterdam, 2003.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 2.047

An oversized press mould

The highly developed Gouda pipe industry had classified its products into categories. The maatpijp was the pipe with a certain standard length. All pipes longer than that type were indicated with bovenmaats or oversized. They were products with a stem length of over 21 inches or longer than 55 centimetres. The longer pipes went up in four steps, each with its individual name. They were made only by the best manufacturers, who were able to attract work force capable of doing this difficult job.

Such a manufacturer was Willem Begeer, since 1792 master pipe maker in Gouda. In his company he focused on the higher quality category, not surprisingly including the oversized pipes. A really well equipped manufacturer even delivered every stem length in two versions. The smooth one as standard pipe, obviously the most commonly sold. In addition, a worked version was made, a high-decorated pipe that was donated as a gift to a gross of ordinary pipes. Of course, these pipes were also available separately, usually in quantities of a quarter of a gross because the higher price kept their sales limited.

This so-called 33 inch press mould was engraved around 1815 at the request of Willem Begeer. The press mould consists of two parts that close with pin-hole connections. The bowl of the pipe is engraved with the coat of arms of the city of Gouda, framed by a ribbon saying "PER ASPERA ADASTRA" in other words along wayless roads to the stars. The shield is held by climbing lions, the heads turned away of the shield, standing on a simple lambrequin. Interesting is the reverse of the bowl. Here the coat of arms of the city of Bremen is shown, consisting of a slanting key.

Even the stem of this pipe has been extensively decorated. It starts with a band of shells and continues with a swaying floral tendril with bunches of grapes. In the windings of this tendril, minute jumping dogs are punched as decoration. At the centre of gravity of the pipe this branch is interrupted by a band with an oblique twist. On the stem Begeer mentions his name as a signature. The last piece of the stem is undecorated.

With a stem length of almost ninety centimetres you wonder who has been the target group for these pipes. This question is explained by the coat of arms on the reverse of the pipe bowl. In the German Hanseatic cities the oversized pipes were extremely popular. They were smoked in coffee houses, but also at private homes. Both men and women eagerly used them. It is therefore not surprising that Begeer put the Bremer coat of arms on the pipe bowl to satisfy his German customers. By doing so, the pipes matched the consumer demand in that region optimally.

How long the press mould has remained in use is unknown. A complete pipe from this mould was not retained. Supposedly the production stopped already with the death of Willem Begeer in the year 1844. Two other manufacturers have then had this press mould in their possession, but it is not clear whether they actually made production. From a functional point of view, this was certainly possible because the press mould doesn’t show excessive wear. It was the changing fashion that caused that these extremely long clay pipes were no longer in demand. Waiting for new production, the press mould survived its time and shifted in relevance from production material to museum object.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 10.000

Press mould for a royal pipe

The quality of clay pipes largely depends on the tools that the pipe manufacturer uses. If he succeeds in finding a good mould maker, he will have access to accurate tools for moulding pipes with mimimal finishing work. If that mould maker is able to create figurated designs, new opportunities will arise. Then the pipe maker can offer decorated goods, which should arouse desire in the prospective customer. An example of a cleverly made, but also very rare figural press mould will be discussed here.

It concerns a brass mould in three parts intended for the production of a so-called stub stemmed pipe or pipe with a truncated stem for insertion of a detachable stem. The bowl of the pipe shows the bust of the Dutch King William II, imposingly represented complete with epaulettes on the shoulders and decorations on the chest. On the stem, the sitter is identified by a text: on the right "WILLEM II KONING" and on the left "DER NEDERLANDEN". The stem also carries the shape number 61, an indication of the size of the assortment at the time the mould was made.

The press mould itself is one of the most massively executed specimens in our museum collection. It has an extraordinary thickness caused by the bust widened by the protruding epaulettes. Hence, the thickness almost exceeds the length of the mould, something never occuring. It is also surprising that there are no locking pins as usual. The locking pins were used to clamp the mold firmly in the vice, without the three mould parts being able to shift, so that the end product is flawless. With this exceptional mould, the locking pins can be missed because the three parts fit together so perfectly that they lock together without any movement or friction. However, a round ridge has been fitted on the underside of the mould for a correct position when standing in the vice.

There is some uncertainty about the origin of this press mould. The shape itself does not show any indication of the producer, nor the brass fouder, nor the pipe maker. Only one pipe is known from this mould, marked JK of the pipe maker Jean Jacques Knoedgen. This maker first worked in Liège and Maastricht before he decided, after the Belgian secession in 1830, to settle in Brée, Belgium in 1846. Since William II became king in 1840, it is certain that this mould must have been made sometime in the late 1840s. He reigned until 1849, so that leaves only a few potential years for production. But whether Jean Jacques Knoedgen commissioned this press mould remains to be seen. His company was only modest in size in the 1840s. It is possible that he took over this tool from an ancestor's inventory, because Jean Jacques comes from a extended family of pipe makers. Another possibility is that this special press mould entered the Jean Jacques Knoedgen workshop after 1850, for example through a bankrupt factory. Only the discovery of a print from this mould with another, older pipe maker's mark, can solve this mistery.

What we can confirm is that the press mould has not been used intensively. This is evident from the extreme rarity of actual pipes in this shape. Another indication is that hardly any wear can be detected on the tool itself. The early and unexpected death of the king could be the reason for modest production numbers, but also at the location of Knoedgen. In his time, trade from newly founded Belgium to the Netherlands was impeded by import duties. The fact that William was King of the Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg, with no duties in Belgium any longer, only reduced the sales area. These restrictions will have contributed to a modest sales result. It therefore appears that the manufacture of this exclusive mould has not been a profitable action after all.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 23.713

Bomb bowl press mould

For a museum, it is attractive to focus on the exceptions, because that gives you an eye on the extremes of the past. When we talk about size, it is about the miniatures at one end, but as opposite also about the largest, the heaviest and most impressive. Well, this pipe mould is such an extreme, although you wouldn't immediately say that from a picture. However, its length is more than 90 centimeters! The pipe that is pressed from this mould is known as a bomkop, literally bomb head, a Gouda pipe with an oversized or water-head bowl and a long straight stem. It is therefore a giant brass press mould, as usual in two parts and equipped with seven iron locking pins. This mould was used in the production of the bomkop, over-sized clay pipes for special purposes. Not intended as a smoking pipe - a complete package of half an ounce goes into the pipe bowl - but rather as an advertising item. The dimensions prove that these are giant pipes: a bowl height of eleven centimeters and a stem more than seventy centimeters long. The weight of exactly fifteen kilograms makes it a tool that is extremely difficult to handle. Nevertheless, the shape has retained the standard Gouda model with an oval bowl with heel and a long straight stem, so that the article still is recognizable to the customer as a Gouda pipe.

However unusual it may be, the tool has been in service for a long time and that certainly left its mark. The mould has undergone several minor repairs and adjustments. For example, a rectangular piece of lead solder has been installed in the right half of the bowl as a repair. The crown, the zone above the actual pipe bowl, has even been repaired a number of times. It is unexpected to see no less than ten guiding pins around the crown to ensure that the stopper was guided in the correct direction into the mould. We also see a change at the stem end behind the button mouthpiece. At that point, the stem was narrowed with lead solder to better guide the wire. In addition, the stem was shortened around the year 1900 and provided with an additional button knob mouthpiece. From that moment on, the pipe had a stem length of only 49 centimeters. This was done under the last owner, forced to do so because he had no baking facility for pipes over half a meter in length. This maker also stamped the inscription "M.N. V. DUYN".

On the right side of the heel the Gouda coat of arms is applied, on the left of the heel we see a dot as a mould mark. Both markings point to a Gouda tradition that has lasted for generations in which the side mark was the ultimate status of the Gouda product. The mould mark refers to a large-scale production with several moulds of the same shape, each with its own mould mark as a distinction. That is rather ill-conceived in this case, because it is unlikely that a second bomb head mould was in use in Gouda at any time. And would that be the case, certainly not at the same factory. So the mould mark really stands out from the tradition.

The last pipe maker to own this mould was the Van der Want factory, who bought the press mould in 1953 together with a few other specimens from the descendants of the Van Duyn family. That was when Georg Brongers showed interest as curator of the Niemeyer Dutch Tobacco Museum. Manufacturer Dirk van der Want wanted the pipe makers tools to remain among the pipe makers in Gouda. For that reason he bought this mould together with other redundant tools. His plan was successful, although there was no longer any production. A generation later, the mould was given to a well-known Dutch collector who ultimately sold the object on to our museum.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.363a