Interesting invoices from a sold-out factory stock

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Interessante rekeningen van een uitverkochte fabrieksvoorraad

Année de publication:

2013

Éditeur:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Description :

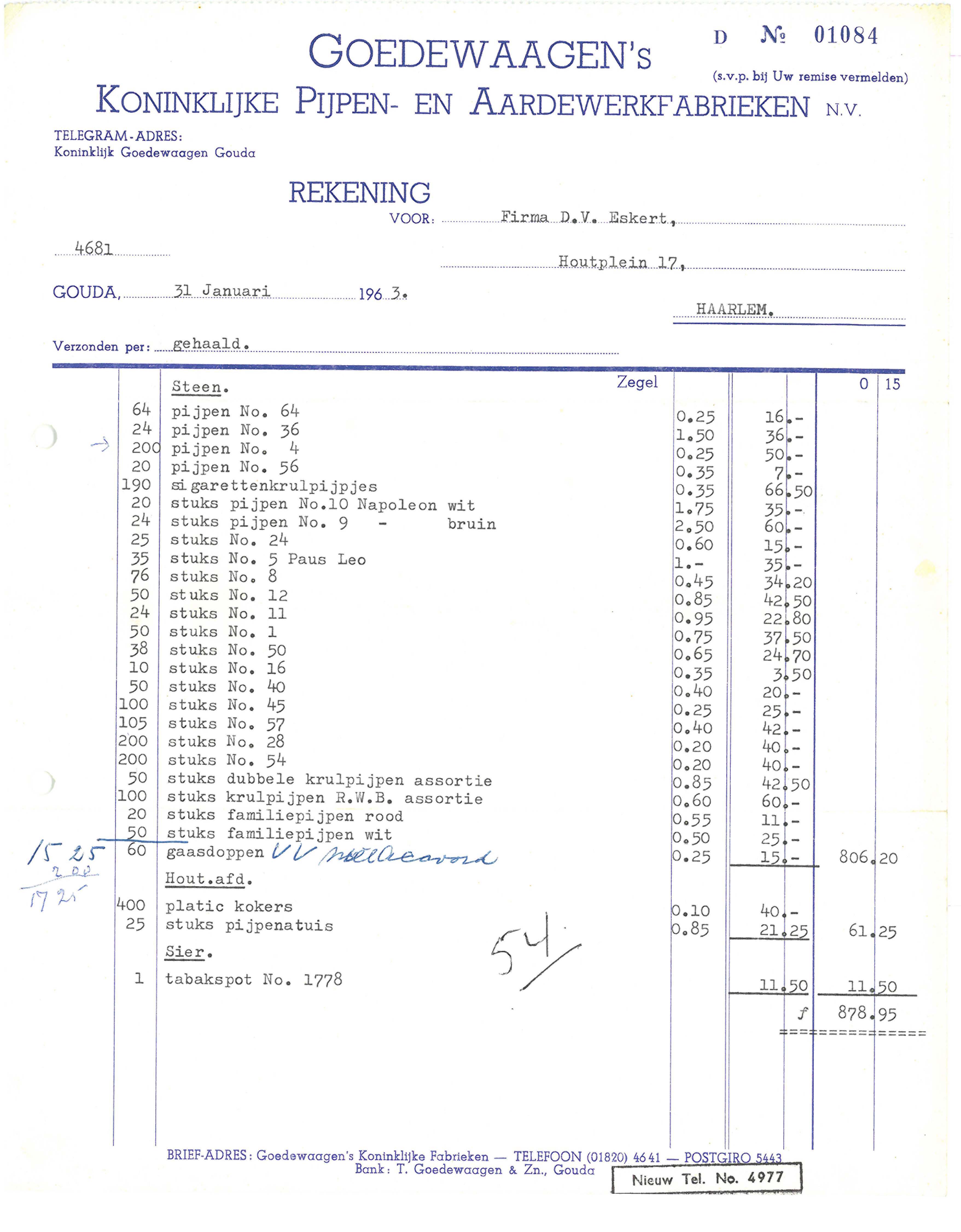

Invoices from the Royal Goedewaagen issued to the Van Eskert firm in Haarlem reveal information about the stock of clay pipes in 1963.

This year it is exactly fifty years ago that Koninklijke Goedewaagen cleaned up the attic with their stock of obsolete clay tobacco pipes. That happened during the big innovation and transition to mechanized production. The Gouda factory would no longer be a trade company for manual work, but a factory focused on large-scale mechanical production. At the same time, the clay pipe was pushed away by the ceramic tableware at Goedewaagen, and logically the pipe section was therefore reduced for the purpose of serial production. This article is about the sale of this old stock of clay pipes. Crown witness is a set of invoices from the most important customer, who bought more than six thousand historical clay pipes (Fig. 1). These invoices give us insight into the old stock and what ultimately happened to sell this out. A wonderful story about the passage of objects through time.

The phenomenon of stock

In the nineteenth century the assortment of the Gouda pipe factories grew because the clay pipe became gradually a fashion item. It was wise to keep a large stock so that quick delivery was always possible. When stock of pipes was insufficient, as many employees as possible switched immediately over to the ordered shapes. It was possible, but less profitable when this work had to be outsourced to another workshop. With the assignment to a so-called buitenbaas (outside boss), the profit was obviously skimmed off. Not surprisingly, therefore, the established companies had substantial stocks. That choice was partly justified because the product was eternally sustainable and little changeable. Moreover, the product was not very investment intensive.

The stock in the warehouse consisted of current trading and less marketable goods. These obsolete stocks even included pipes that were left over for generations. In many cases, it was about quantities of less than one gross per type, which, given the scale of the trade, were difficult to sell. The gross unit was in fact the starting point for sales from the factory. Among the older stocks were pipes that had fallen out of favour and that could not easily be sold anymore, this could involve many gross. The maintenance of obsolete stocks was illustrative of the common thrift and economy among manufacturers at the time. Taking a loss was not in their habit, they rather waited their chance for a favourable sale. In addition, the manufacturer was also a trader and often bought up obsolete material from other producers to prevent price decay with the hope of making a good profit one day.

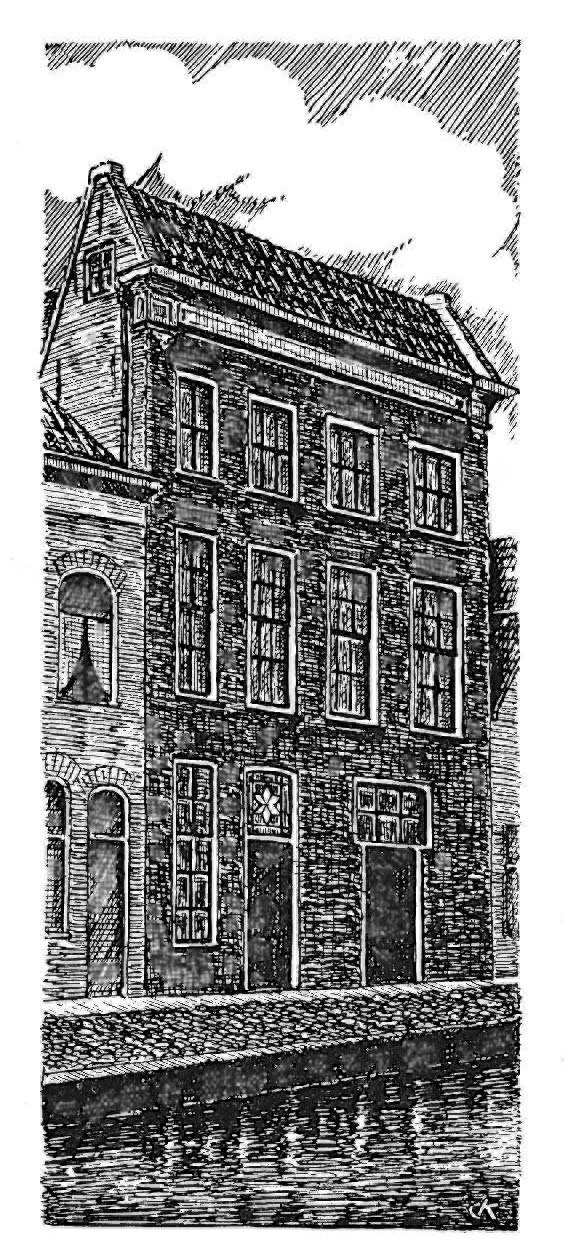

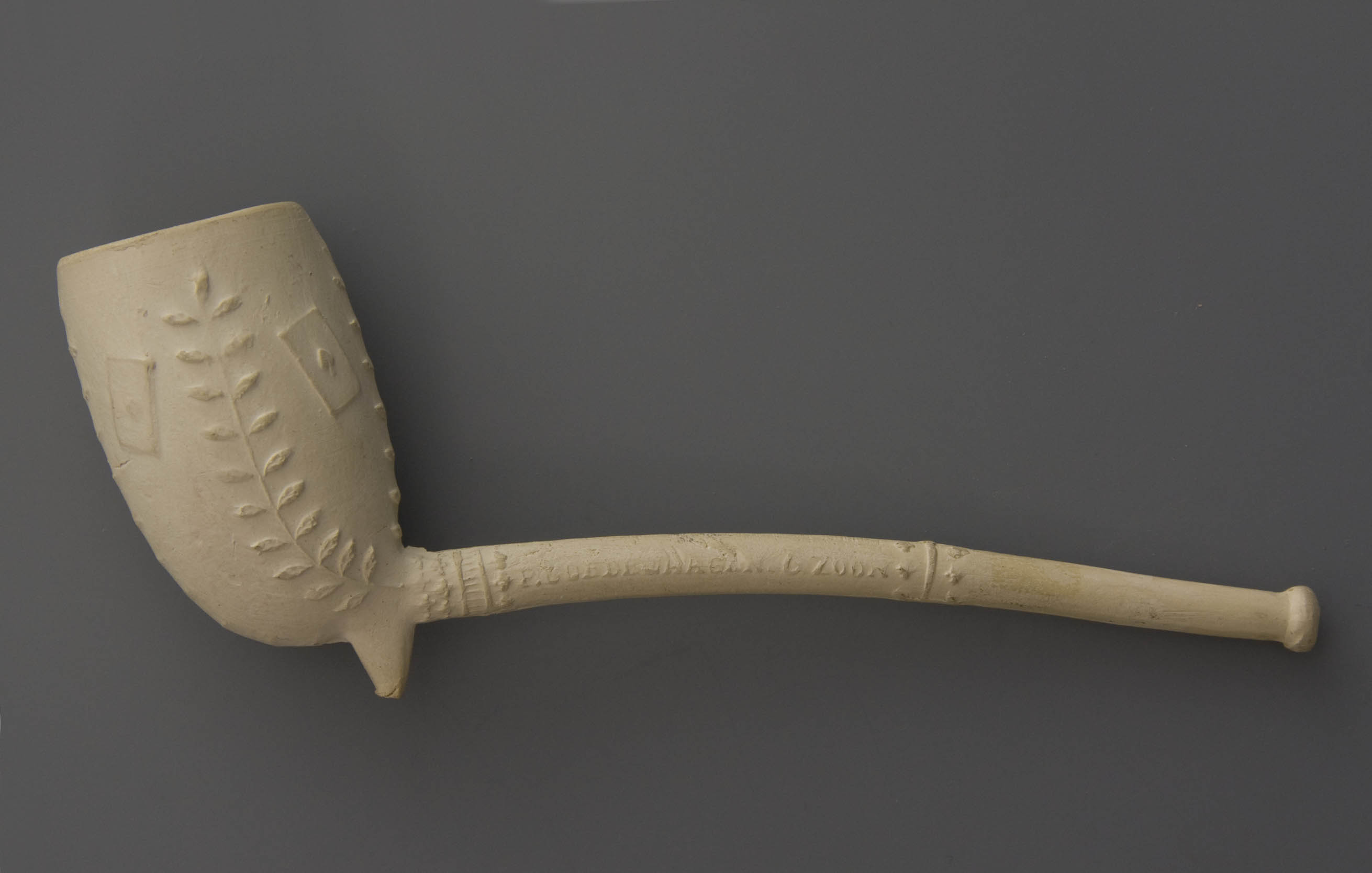

At the end of the nineteenth century, the firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons (Fig. 2) had attics filled with clay pipes that are neatly described in their yearly inventory. Here too a distinction was made between current and obsolete. The latter category included dated articles but also remnants of other factories such as Bartholomeus van der Maas or the French firm Duméril (Fig. 3). Those dated stocks accounted for a significant part of the company's assets, although their returns were small. For example, the factory inventory reports more than 5,900 gross current pipes in 1885, compared to more than 2,400 grosses of irregular stuff. Two years later, more than 2,700 gross current ware against more than 3,700 gross unsalable pipes. These figures illustrate the sharp fluctuations per year and it becomes clear that the pipe trade was driven in the light of these stocks.

The twentieth century changed a lot in the attitude towards the stock. Scarcity of labourers reduced the current stock. In addition, the introduction of the ceramic tobacco pipe around 1910 made the pipe more fashionable, while decorations were more often tied to current events. Working for the stock was no longer an option. In addition, the preservation of ceramic pipes always has a risk for hair cracks, oxidation in the metal ferrules and even in the durance of the rubber and plastic mouthpieces. Besides, the consumer was also more focused on changes in the pipe. Finally, the production price of the ceramic pipe was significantly higher and the investment therefore much larger. Stock holding became out of use but given the large number of pipe shapes and the desire to deliver quickly there was always a balance between stock and turnover.

The pipe warehouse

In 1909, a new factory complex was built by P. Goedewaagen & Sons, located on the Nieuwe Vaart just outside the Singelgracht of Gouda. In addition to the main building for the production of pipes, a large pipe warehouse was put down (Fig. 4). That building covered two floors each with an area of more than four hundred square meters. The stocks of finished products were stored on the main floor of this warehouse. The common pipes were stacked in standard cases, so called nulletjes (nulls) on the ground floor. The old stocks and leftovers are placed on the first floor in timbered wooden racks. In the current merchandise there was a lot of circulation, but with the stock of obsolete pipes there was only selling on special demand. It is quite unexpected that the factory worked so limited with the real old stocks. It seems that it was easier just to keep them than to promote them in order to sell them out. The management feared that following orders could not be delivered at the same price because of the change of production costs.

The warehouse supervisor kept office downstairs. He managed the stocks of incoming and outgoing cases and supervised the shipments. Numerous cases with pipes in current production were within reach to be handed out as samples to prospective customers, or sent out. It was customary to write the shape number with pencil in the pipe bowl as a reference so that orders could never cause confusion (Fig. 5).

Between 1909 and the 1950s, much changed in this pipe warehouse. With the introduction of the ceramic pipe as early as 1909, a modest workspace was set up on the ground floor of the warehouse. There was even a kiln built for glazing, so gradually more and more storage space was taken into use for production. In a factory building, it is simply irresponsible to keep storage space if production can take place at the same spot. Eventually the stock of finished product was all stored on the first floor.

During the interwar period, we see the stock of pipes alternately decreasing and increasing again, just as the production and sales ratio is. Overall, the stock of press moulded pipes shrinks due to a lack of workers. We are not informed about the extent of this obsolete stock between the two world wars. The stocks of ceramic pipes (doorrokers) and the more luxurious hollow-walled, so-called baronite pipes were added respectively from 1910 and 1921onwards and never became excessively large. In 1934, for example, almost 7,500 colouring pipes (simple glazed ceramic pipes) and nearly 2,300 baronite pipes are in stock. In 1940 this was 4,500 and just over 1,100.

It was not until the 1950s that the layout of the buildings of Koninklijke Goedewaagen changed drastically. The envisioned reorganization of pottery production necessitates rearranging in larger spaces for, for example, mechanical turning of plates. The old pipe warehouse is definitely getting a function in production. Much of the old, mostly unsalable stock had to be cleared, to make space for new activities but also to generate money for investments. The pijpenmagazijn designation disappears and the obsolete stocks are stowed away at random places in the attics of the main building.

Reorganization and clearance

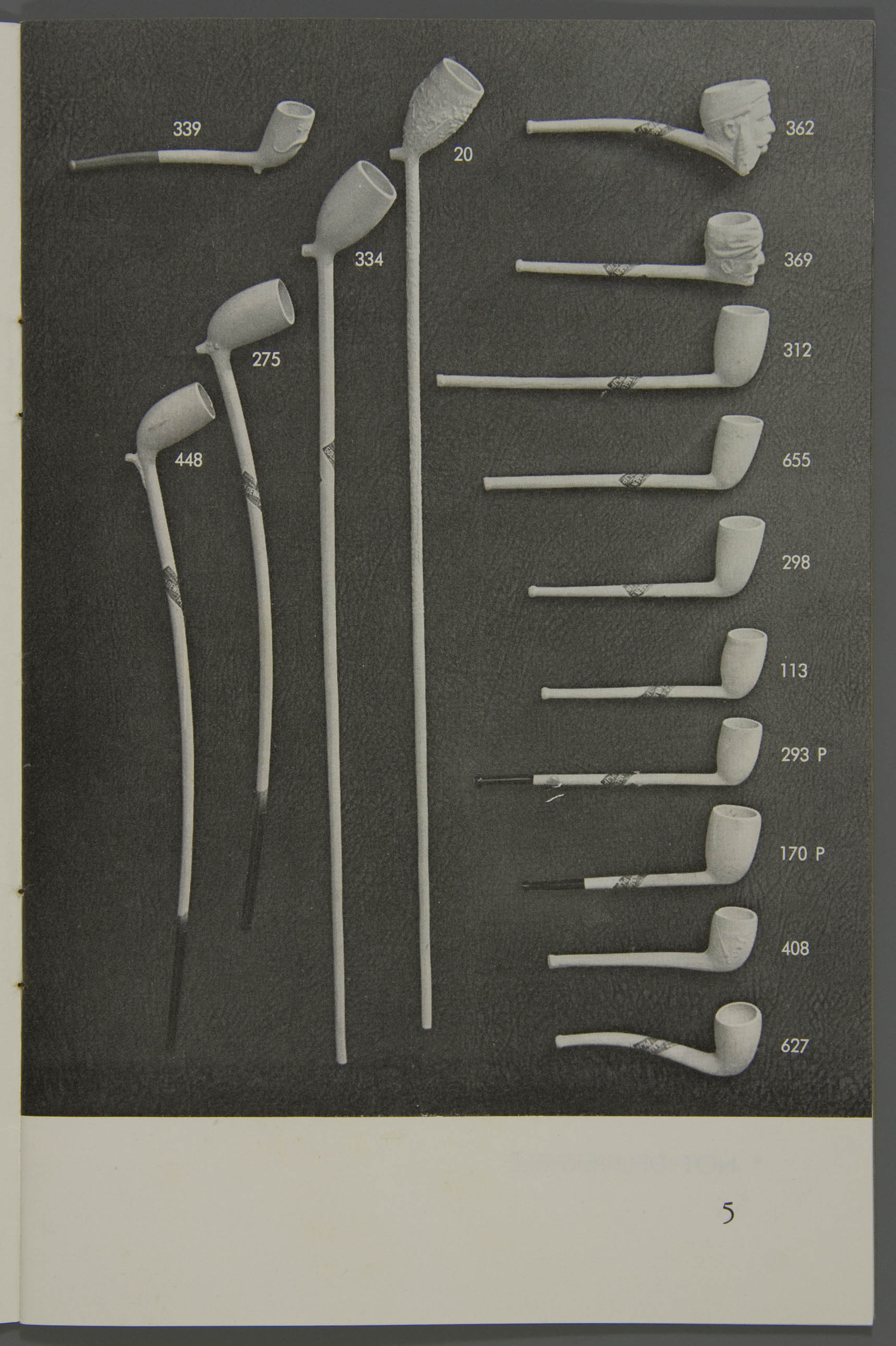

It is clear, Koninklijke Goedewaagen sets a new course in the fifties. In order to survive, the factory has to switch from hand labour to mechanization. In addition, the future lies in the ceramics such as dinner services, not in the pipes. This decision means a major change in the assortment as well. The line with press moulded pipes is drastically reduced to only fifteen shapes (Fig. 6). A decorated and a smooth standard long pipe, two shapes with lacquered stem ends with different bowl size and further some short stemmed pipes in different shapes. For the last smokers from clay pipes, this limited choice should be sufficient.

At that time also the range of slip casted ceramic pipes is slimmed down. Only seven shapes of "colouring pipes" are kept in production, along with a few baronite pipe shapes, including the calabash design. As a curiosity also three baronite portrait pipes of American presidents are maintained, as well as a horse's head. The category souvenir includes some classic shapes sold under the name Old Dutch: a German stummel and a so-called wine pipe. From this slimmed-down range, a new catalogue will be published that is supplemented with briar pipes purchased elsewhere and some smoking accessories. With this expansion, Goedewaagen hoped to be able to continue delivery to the tobacco retailer.

Meanwhile the old showroom for pipes was dismantled in 1958. This decisive step can be seen as the end of a characteristic era in the factory history. The transition from the clay pipe factory to a modern ceramic company was definitive. The material archive of the showroom carelessly disappeared into a large chest in an attic, heading an unclear future. In the renovated showroom, a select number of smoking pipes was on view, rather subordinated to the ceramics, a conscious marketing strategy. Had it always been customary to keep stocks, in the 1950s stock was seen as obstructive.

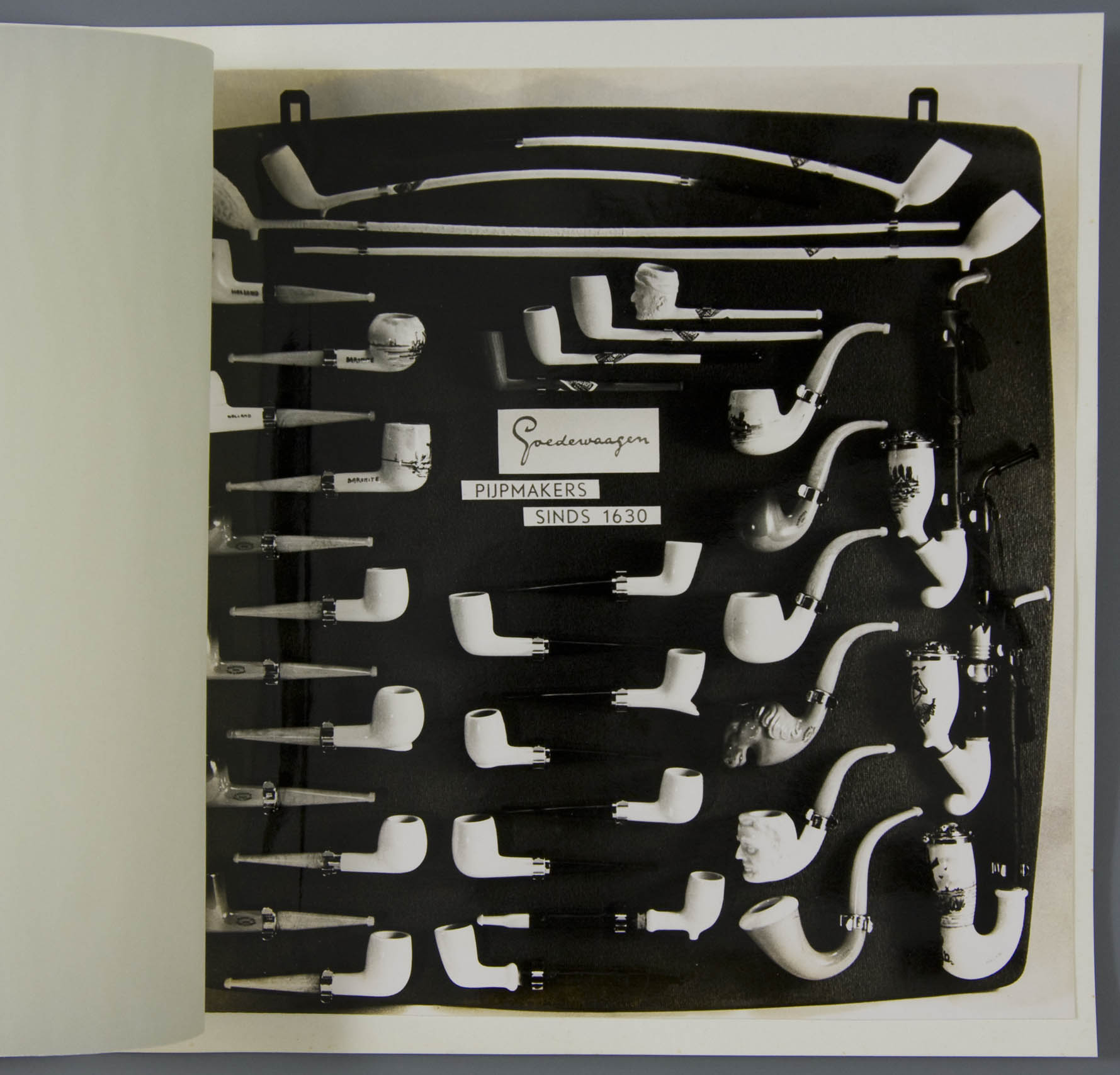

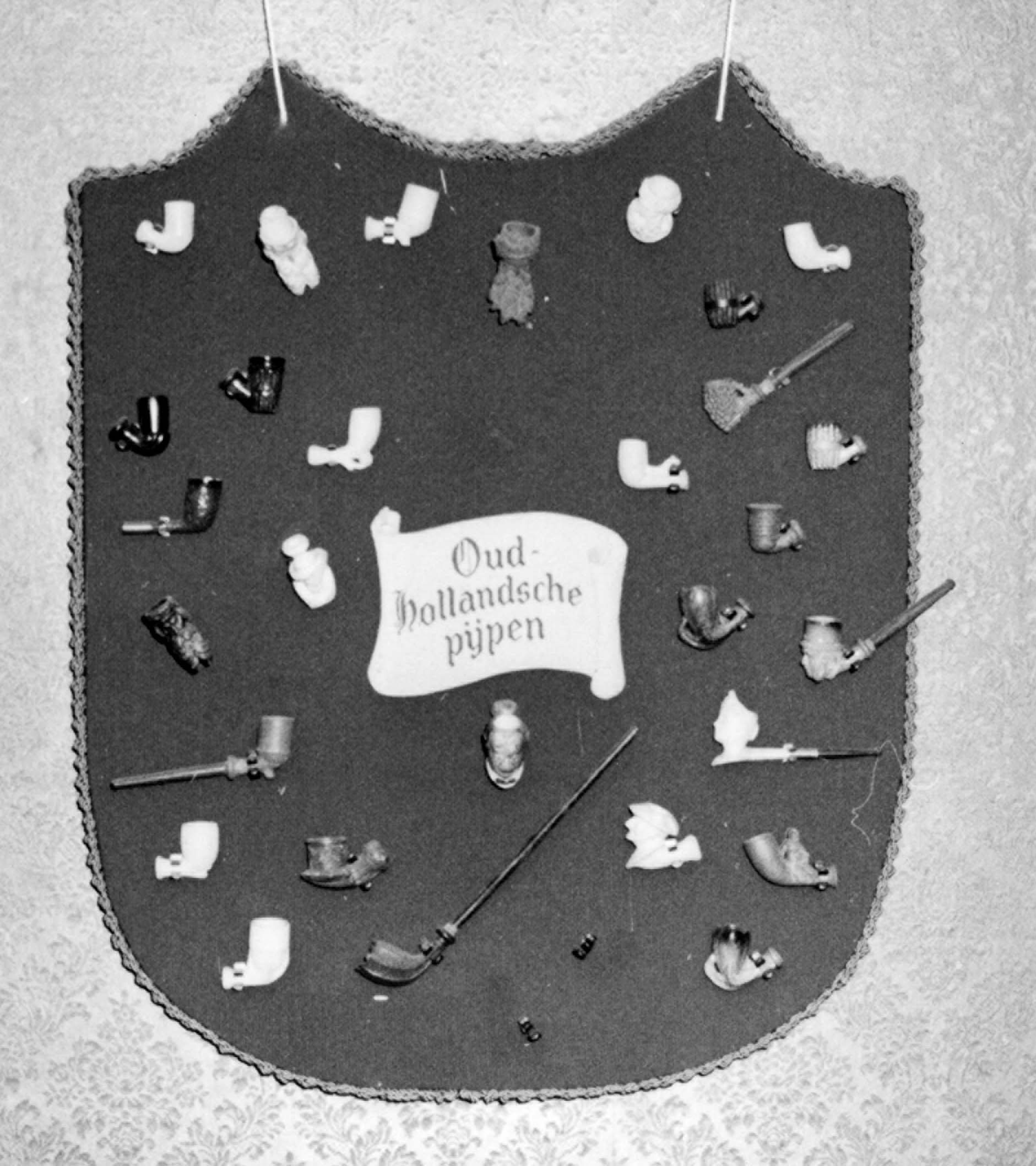

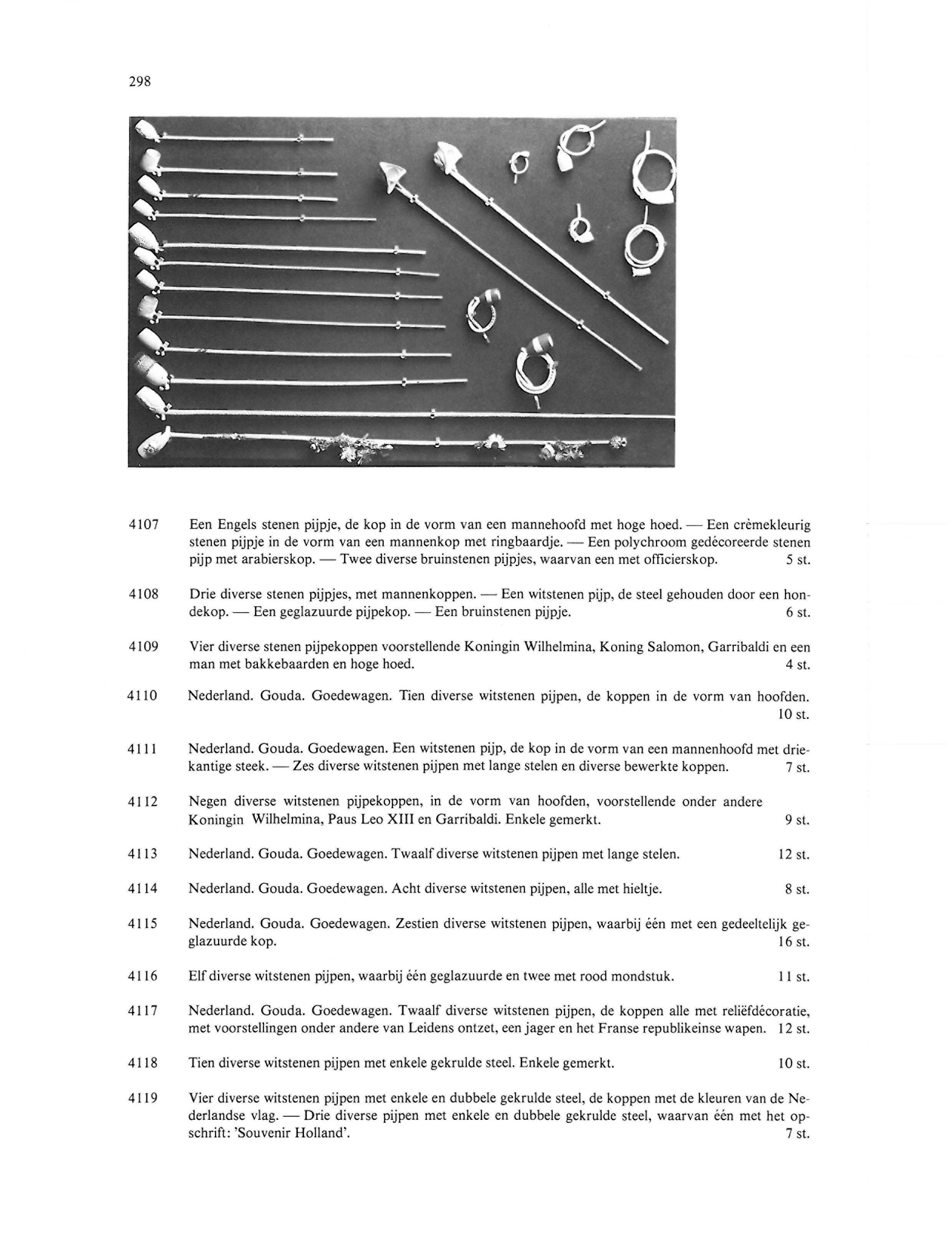

The clearance of the pijpenmagazijn, the warehouse started from 1955 when as noted both space and resources were needed for the mechanization in the pottery. The sale of the old stocks was stimulated by the factory representatives. Head of sales Cornelis Römer was commissioned to offer specific groups of pipes at an attractive price to existing customers. An important asset in the sale of the stock was the pijpenpaneel (pipe panel) devised by Römer (Fig. 7). On a square plate covered with gray-blue plastic, an attractive-looking range of pipes was attached with pipes from the stock, in addition to common stuff. The pipe panel was a great success and came to hang in many tobacco shops. It seemed like the return of the Dutch clay pipe and its ceramic counterpart.

Yet the sale of the obsolete clay pipes did not go smoothly. Assorted groups of old pipes were sold but the market was limited. Most tobacco shops had a nice presentation object with the pipe panel, but it only came to sale little by little, let alone to follow-up orders. Situation was better in a handful of stores that could focus on old, obsolete objects at a higher sales price. Gouda tobacco stores were important customers for Goedewaagen because they were able to sell to tourists. The cigar shop De Herder, Jaske and Van Vreumingen turned out to be the kind of souvenir shops that actually sold the clay pipes. Similar stores could also be found in other tourist places: Hoorn, Enkhuizen, Volendam, Delft and Scheveningen. These shops were personally approached for the takeover of tail ends. Even in the 1970s, some of these stores still had residual stocks, which say something about the slow circulation of old-fashioned smoking pipes.

The most important customer

An unexpected turn in the sale of the stocks from the former pipe warehouse is made by the Van Eskert couple from Haarlem. They ran a store at the Houtplein 17 which dated from 1907 and was set up by the father D.H.J. van Eskert (Fig. 8). Son H.J. van Eskert joined the business in the 1930s and continued the store. After the Second World War he became the owner together with his wife. They continued their old-fashioned cigar store where craft and tradition were an important element. All in all a neat shop with a solid interior and optimal service.

H.J. van Eskert and his wife became acquainted with Pelser, the new representative of Koninklijke Goedewaagen, during a visit to a souvenir fair in January 1963. At their booth at this fair, Goedewaagen decorated a corner with traditional clay pipes from the old factory stock. Mrs. Van Eskert did see trade there. They bought a batch of no less than eleven hundred pieces in only six varieties. It was an offer of the simplest clay pipes for less than two dimes each. On January 21, 1963, the representative delivered the order personally.

In anticipation of successful sales, the couple went to Gouda ten days later on a Tuesday afternoon when their store was closed, to visit the lofts of the pipe factory to inspect the stocks of clay pipes. There they found, quite disorderly stacked, an immense storage, despite the fact that the sale already started years before. The couple Van Eskert brought five follow-up visits to the factory within four months. During those visits they bought all the better types of clay pipes from the attic. With this buy they acquired a monopoly position in old clay pipes from Koninklijke Goedewaagen.

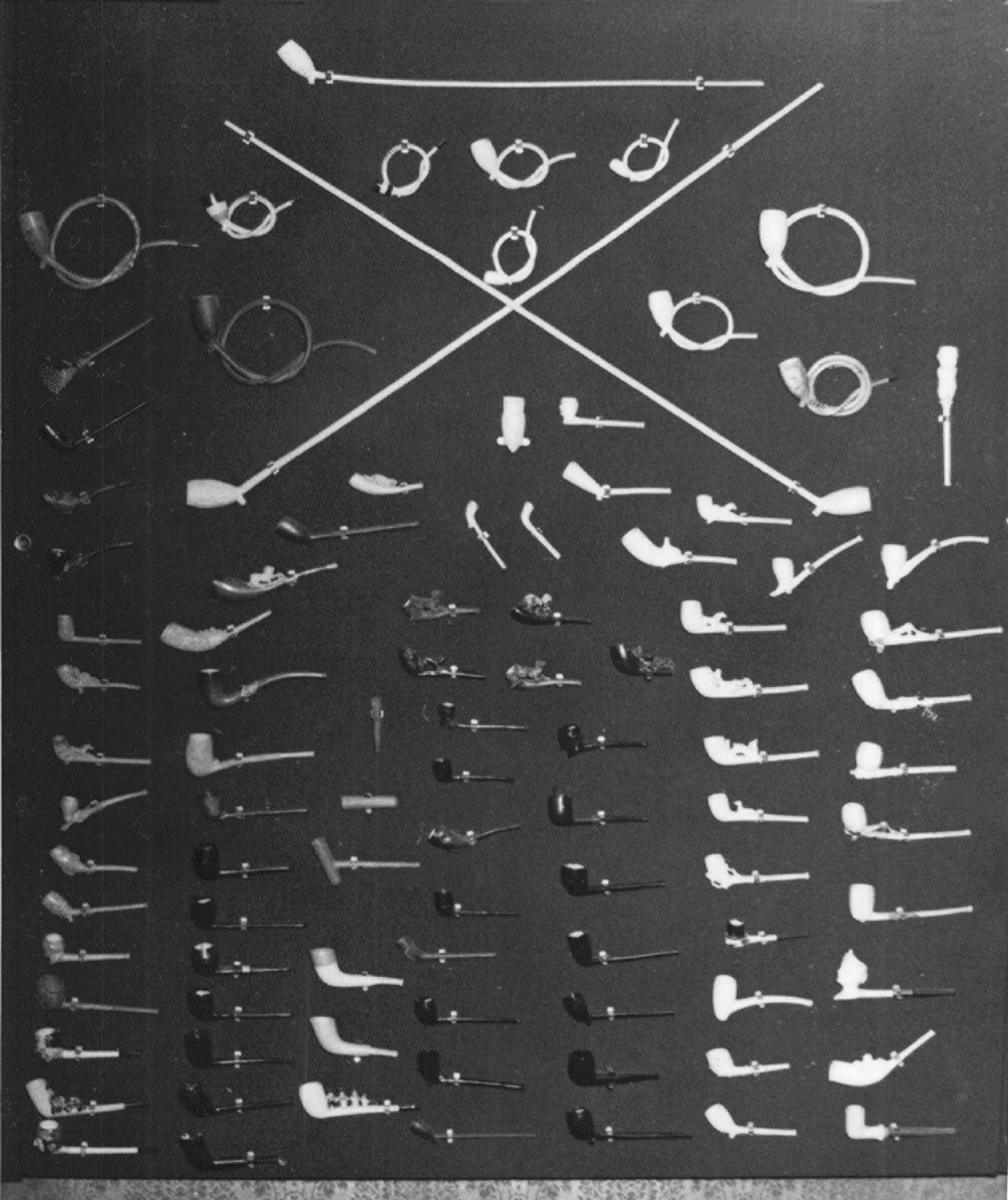

Initially their purchase was aimed at resale in their own shop but soon they got a deeper interest and the couple started to collect themselves. A copy of each pipe shape was kept separate for their own collection. This collection was exhibited on four large panels in a room behind their store at the Houtplein (Fig. 9). After these factory visits the variety was well over three hundred pieces and resembled the original showroom collection of Koninklijke Goedewaagen.

The enthusiasm of the vendors, especially from Mrs. Van Eskert, ensured that countless customers started collecting these traditional Gouda pipes. These enthusiasts came from various ranks and from all over the country. Some were mere collectors and started a collection of old pipes by buying something new at Van Eskert every time. The Italian Ivo Tribioli, for example, was one of the more specific customers, which showed particular interest in smooth, traditional Dutch pipe shapes. In one sale he purchased a group of eighty stemmed clay pipes of different kind. His characteristic view on models and shapes made him choose pipes that the Dutch enthusiast would never go for. Stan Konings worked in Tilburg as a tobacconist and bought a collection of Goedewaagen pipes via Van Eskert as decoration for his shop. Collectors with a certain commercial activity also showed interest. In the Netherlands it was Fred Tymstra, in Germany Rainer Immensack. American pipe collector Benjamin Rapaport recorded the pipes of Goedewaagen in his sales catalogue that was circulated in the United States.

The couple Van Eskert was convinced of the uniqueness of their offer and corresponded all over the world to market their clay pipes. The trump of it all was the so-called grand collection, the panel with three hundred pipes hanging behind the store. For this special group an asking price of ten thousand guilders was devised, simply because it was the largest collection of Goedewaagen pipes. A collection of one hundred pipes was priced at four thousand guilders. Smaller collections of thirty pipes on a panel was offered for one thousand guilders, which the Van Eskerts considered as a bargain. With a price of thirty to forty guilders per pipe this was experienced as extremely expensive by the Dutch collectors. At a random cigar store that still had some old stock, a similar clay pipe from Goedewaagen would cost a few guilders at most. The pricing was based on the idea: the more variety, the rarer and therefore the higher the unit price.

Incidentally, the sales were not only about the money, also the game and the unexpected contacts around the pipe trade were important. Van Eskert enjoyed the visitors with interest in their pipe collection. By showing the large collection in the room behind the store, she enjoyed telling stories, showing her enthusiasm for the material and owner's pride. As an extra, the two brass press moulds always appeared and the original catalogue they possessed, but not for sale. Those objects were unique in the Netherlands at that time.

The total purchase

Thanks to an envelope with seven invoices that the son of the couple Van Eskert gave me years ago, we know exactly what Van Eskert has purchased at Goedewaagen (cf. Fig. 1). Seven specified invoices, written out over four months, give us insight into what was bought, in what quantities and at what price. In total, more than 6,500 clay pipes were purchased at a total price of 2,378 guilders. On average that amounts to just over 35 cents per clay pipe. In doing so, Van Eskerts interest quickly focused on the better qualities with a preference for long pipes, well finished materials or decorated products.

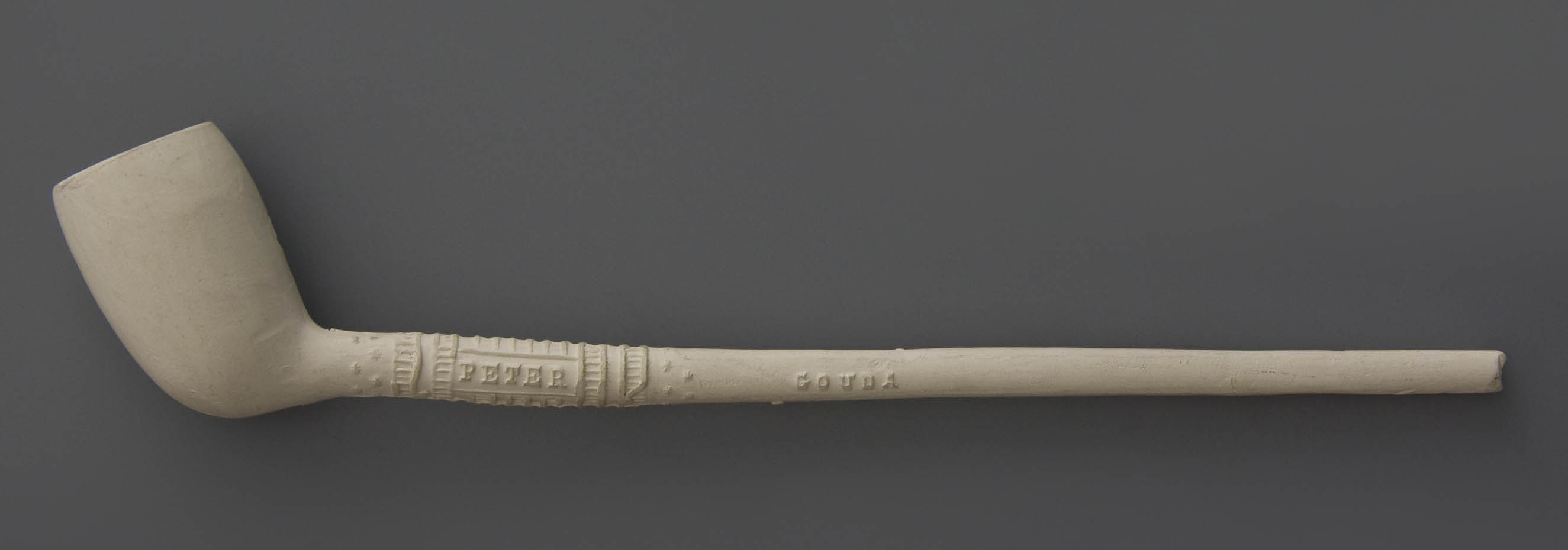

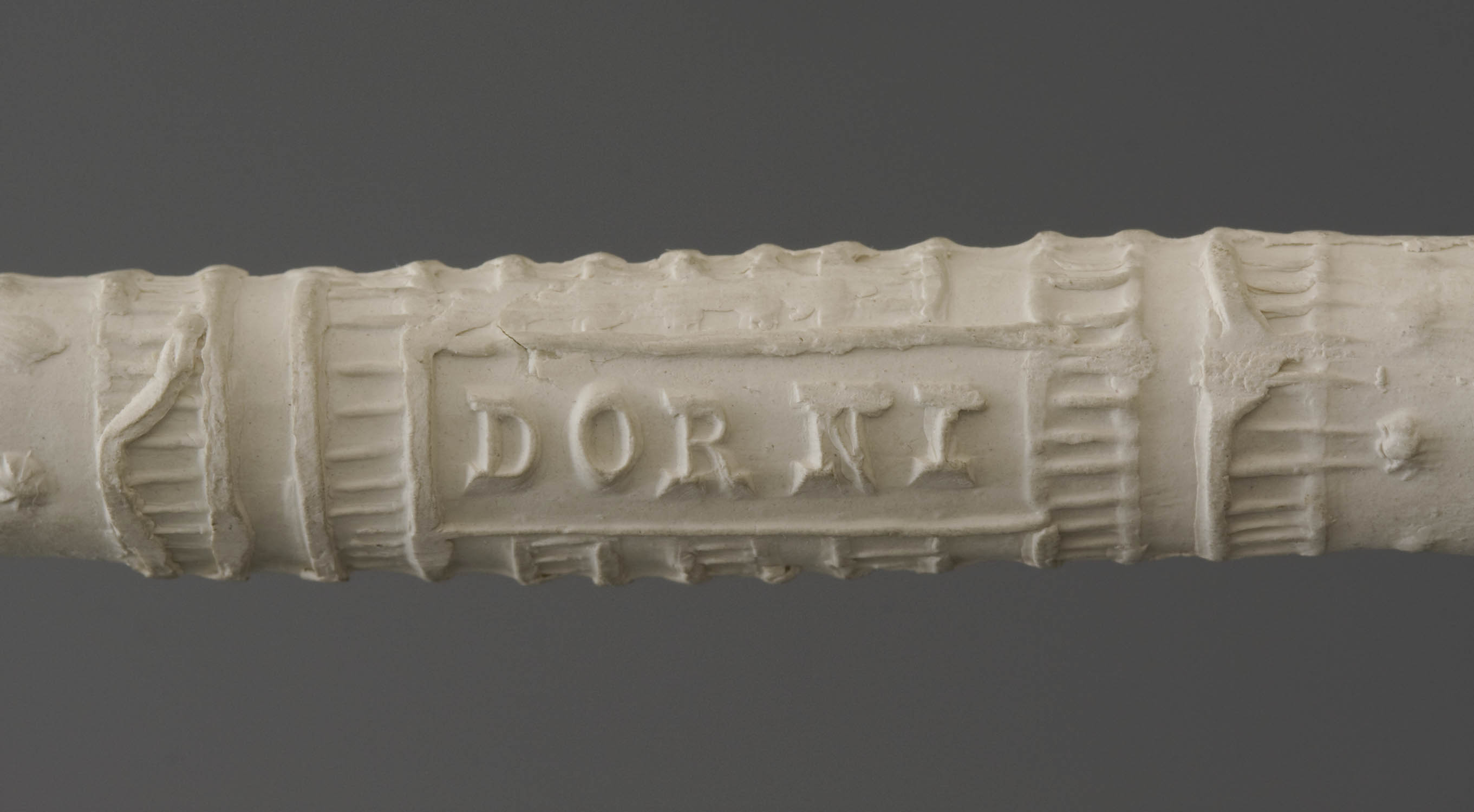

As said, the invoices provide insight into the prices. These prices varied in 1963 at the factory from ten cents each for the humblest pipes to a rijksdaalder (2,50 guilders) for the most expensive varieties. Standard clay pipes with a short stem are between ten and forty cents. Among the general shapes are the Van Balma beaker, the smooth Isabé and the Peter Dorni (Fig. 10), three simple pipe models that have been in stock for more than half a century. Stub stemmed pipe bowls go for 25 cents. In the category fifty cents to a guilder we find the more special species. For example, the family pipe at a price of fifty cents in white, in red 55. The famous shoe polisher (Fig. 11) and other products in glazed version cost sixty cents. Of these, no less than 470 were taken over! For the pipes with single twisted stem 60 or 65 cents had to be paid, the double twisted stem is 85 cents.

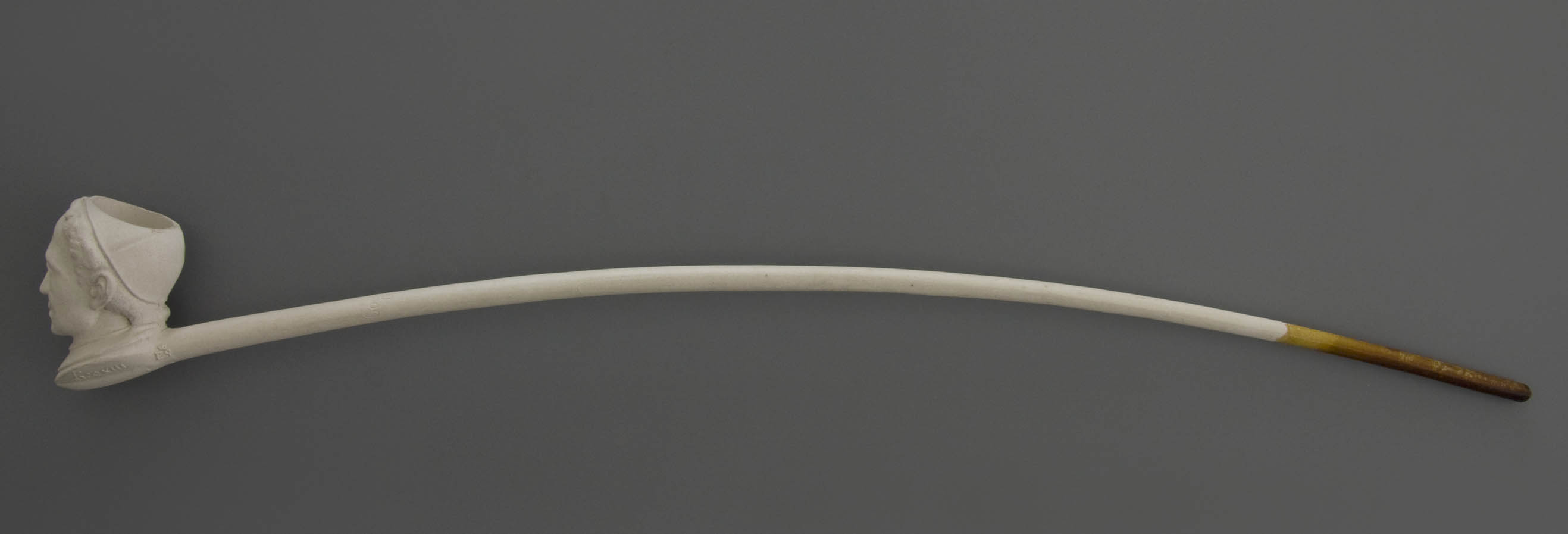

Above the guilder we find the more prestigious material, of which no large numbers were available anymore. The special Pope Leo lacquered stem end cost a guilder, 35 copies of this specimen were purchased (Fig. 12). The meter pipe, at the time the factory's flagship pipe, was one and a half guilders and the total stock of 25 was purchased. Noteworthy is the entry of a pipe with the name Napoleon, a design that was never delivered by Goedewaagen. This is where the administrator of the factory was mistaken, because it concerns the long pipe with the portrait of Peter Stuijvesant (Fig. 13). That mistake illustrates of how far the knowledge about the clay pipes got lost at that time. There was still a nice remaining part of that shape. In white they cost NLG 1,75, on another occasion two Dutch guilders. However, the brown-coloured copies cost a rijksdaalder and that is quite an amount of money for that time. In total, 69 of these shapes were purchased.

A phenomenal buy concerns two large batches of stub stemmed pipes, of which no less than two thousand were purchased for 25 cents each. Among them were larger figural bowls produced in press moulds from Belgium acquired in 1880. Also stub stemmed pipes with the portrayal of Lou Caddetou, a stock bought by Goedewaagen already in the years 1910 from a bankruptcy in southern France and which had not given them any economic gain (Fig. 14). They were left untouched in the warehouse for more than forty years. Also at Van Eskert it was not a bestseller.

Most intriguing are the entries on the invoices of the assorted groups, leftovers of irregular nature. This involved various rare shapes that provided for the variation in Van Eskert's own collection. Very probably some of the pipes shown on the panels in the showroom were among them. One of Van Eskert's customers who collected pipes had four such pipes complete with the brass wires for attachment, which indicates that Van Eskert bought pipes from the former showroom indeed.

In addition to pipes in numbers - and sometimes it is really a good number – some unsorted stocks of various rarities have also been taken up. Mrs. Van Eskert herself later told how she occasionally packed some unregulated objects at the bottom of the boxes, filling it up with bulk goods on top. When you had the account drawn up by Jan Koemans at five o'clock, there was not enough time to check everything and the specified number she mentioned was written down. It is clear that we know a lot about the purchase, but not all of it.

The question remains as to how well the Goedewaagen factory sold out its obsolete stock. A good businessman must have felt that with customers like Van Eskert a certain greed has developed that leads to price drifting. That seems gratefully used. We see the clay pipes gradually becoming more expensive over the seven invoices. That may have led to the fact that Van Eskert stops buying after seven visits. More of the same did not offer a supplement for their stock that was already large, so large that it would last for two generations.

Finally, we can compare the prices that Van Eskert paid with the current prices for new clay pipes at that time. Then it appears that the short pipes cost between thirteen and thirty cents at factory price and that is almost equal to the prices of the simple old pipes. The long work goes for around fifty cents and surprisingly with the old pipes the price was even higher. Of course we must remember that the finishing of the old material was significantly better than the product from the beginning of the 1960s. Assuming that these are obsolete stocks, the sale for Goedewaagen has been very favourable.

How it was sold

In a series of visits to Goedewaagen the clay pipes were quickly bought, but the sales ran little by little. This was of course partly caused by the hefty prices that Van Eskert asked. From a souvenir item the product was suddenly elevated to an antiquity and for the customer it certainly took some time to getting used. The sale of the considerable stocks became a task in itself. In the store at the Houtplein, two shields with clay pipes were on display, one as a complete collection, the other to be sold by the piece (Fig. 15). The clay pipes also had a permanent place in the shop window. But the stock was much too large to sell via a regular tobacco shop. Other steps to new contacts had to be made. Personal approach, visit to trade fairs, correspondence with collectors and all other possibilities.

We do not know anything about the prices at the start, although it is certain that they were raised regularly to get an optimal profit. Ten years after purchase the clay pipes were already offered for thirty guilders each, the rarer ones being more expensive. So a profit of about a thousand percent was taken as a rule! Compared with the ordinary tobacconist who charged about one or two guilders for a clay pipe, the Haarlem shop asked a phenomenal price.

Van Eskert had great pleasure in selling out. Because the couple knew the average cost price, each transaction could immediately be translated into the exact profit. But it was also a game in another way. Especially Mrs. Van Eskert was a natural talent in advertising and selling. She knew exactly how to show an object to a customer, at what height and with what look. Then followed the right pep talk knowing very well how to receive full attention. That the content of the story was not always correct, did not matter and was not invalidated by most customers. A black-baked pipe made said to be made of slate, warped pipes - unmistakably second choice - was praised as being deformed by the old age and that was extra special. A nice story was also told about the painted reed stems.

The sale of the clay pipes was certainly not entirely free of snobbery. In the factory business was done with clerk Jan Koemans, thereafter the payment was settled in the office. In the shop on the Houtplein they had to deal with the representative of Koninklijke Goedewaagen and it is even the question whether this was always Pelser himself. But, of course, to the customers the couple spoke about Mr. Goedewaagen as if it was their privilege to be friends and to be able to buy from the director himself. I still hear Mrs. Van Eskert speak about the comments and compliments director Aart Goedewaagen gave her about their clay pipe collection. It almost seemed as if Goedewaagen was a personal friend at their home and had made a stupid deal, as a result of which the Van Eskerts now triumphed with their unique trade. Years later Aart Goedewaagen would tell me otherwise. The sale of the remaining stock went completely by for the management of the factory. They were occupied with more serious matters.

The size of Van Eskert's pipe stock remained a big secret until many decades after their death. In itself, of course, it is logical to never release anything about stocks. The stock records were kept in a diary booklet from the year 1963. During sales that was sometimes shown to prove the rarity of a particular model, but often by first covering the information of the other pipes on that same page. In fact, there was usually the impression that it was the last piece which made collectors faster in a decision. The figures from the preserved invoices now tell us that at the time the serious collectors were much rarer than the clay pipes!

In 1974 the couple withdrew from the business, son Dick van Eskert took over the shop. He had little interest in the pipe stock so the pipes moved with the elderly couple to Nijmegen. The so-called large collection was given a place in one of the larger bedrooms in the single-family house in the Weezenhof. About this large collection the story was told over and over that a rich American had the photos in his pocket, but apparently had no time to buy. In Nijmegen the couple continued their sales unabated in the circuit of collectors and pipe enthusiasts and now their home was welcoming those who wanted to buy a pipe. Again pipes were sold and exchanged, the stock became smaller but never ran out.

From March 1984 a new course was taken. Mrs. van Eskert had passed away and the spirit behind the Goedewaagen pipes was gone. Son Dick van Eskert found a suitable salesman in collector Leen van den Berg who continued the sale of the clay pipes on consignment basis. He proved very successful in doing so. Van den Berg took over the standard clay pipes for the price of fifteen Dutch guilders each, for the more special pipes he had to pay forty guilders each. The collectors paid the double. In 1986 he even sold the large collection to a private individual in Zandvoort and even realized the original asking price of ten thousand guilders. The two special brass press moulds were sold to the Pijpenkabinet (Fig 16).

After a number of years the results of the sales were declining, the collectors were saturated and new customers didn’t came up. What was left remained as a unmarketable stock for about ten years in the attic of Dick van Eskert and was finally taken over in the year 2000 by the Pijpenkabinet. The stub stemmed pipes of Lou Caddetou were still available in abundance, alongside all kinds of short stemmed pipes. Yet there were also some special specimen. A marvellous find, for example, was a series of twenty long black pipes of beautiful quality, that were very much appreciated by Mrs Van Eskert, so that she never stimulated the sale. They were to be exhibited in a pipe stand in one of the showcases of the Amsterdam museum.

Final word

We do not know from many Gouda pipe factories how the final clearing out took place. Most factories sold their stocks to colleagues, but when the industry was almost extinct, this was no longer a possiblity. The Goedewaagen company always had money to invest, so stocks never had to be sold under pressure. When, in the 1950s, it became apparent that liquidation of the stock of clay pipes was a sensible decision, in this case more out of a need for space than the end of operations, this was done. The representatives have made a start with the sale through regular cigar stores. Remaining stocks of clay pipes were sold as curiosities among the tobacconists and souvenir shops until the couple Van Eskert appeared and took over the bulk.

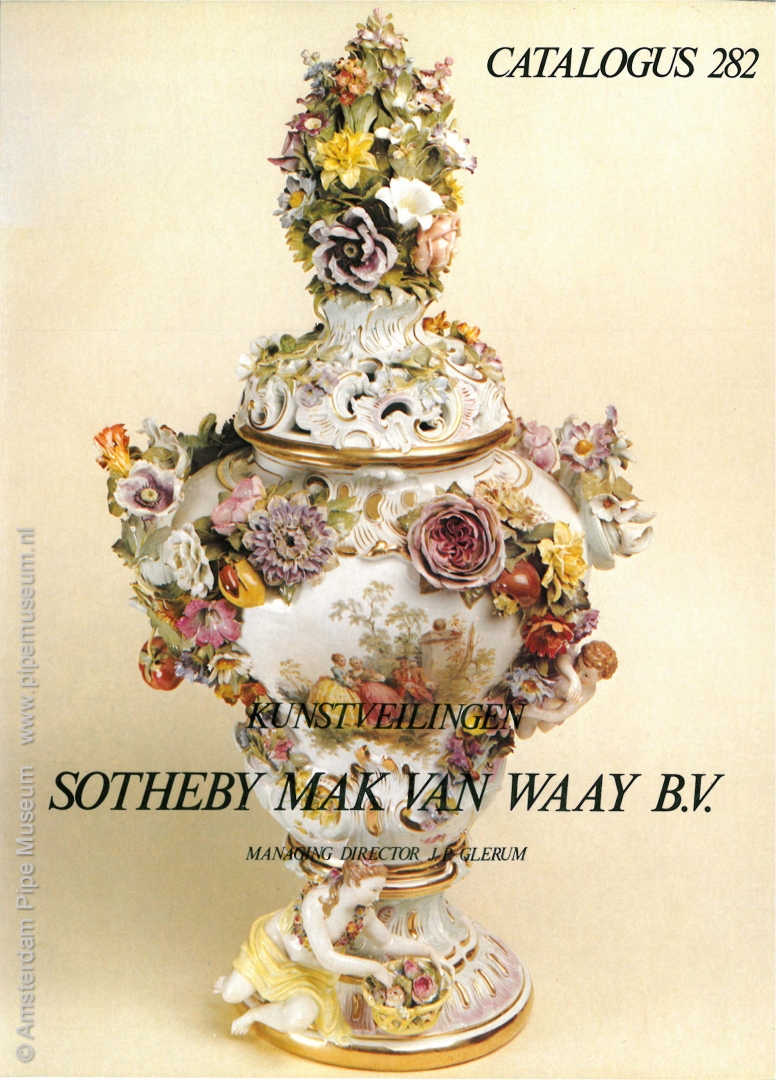

The initiative of one single tobacco merchant created a very unconventional pattern of clearance. They introduced the clay pipe into the collectors' circuit which resulted in a significant impact on the historical image of this product. As a souvenir, a clay pipe does not have a long life expectance, but when it is sold to a collector at a serious price that is different. A high price and an exclusive approach create another appreciation and this way of acting ensured that the Goedewaagen pipes were valued and handled with care. For example, they were sold privately on to new aficionados or even ended up at the auction with Mak van Waay (Fig. 17). In the end they were kept for posterity and that is actually the merit of the pipe trade of Van Eskert.

When we look at the purchase and especially the stock of Van Eskert in the light of the trade, we can conclude even more. The investment that the couple made was considerable and certainly daring for the time. Only with a certain monopoly they could make this investment profitable. Admittedly, collecting was popular in the 1960s and 1970s and nostalgia was in vogue, while the material was difficult to find. On the other hand, opening up the market was the problem back then, both in terms of purchasing and sales. Internet and auctions via EBay did not exist yet, it was not easy to find out what was available and where. There were few fairs for collectors, a closed circuit where the antique and curio trade conducted the monopoly. That trade did not yet see the clay pipe as worthwhile.

Son Dick van Eskert brought the pipe imperium to an end in the year 2000. In that year he sold the last part of the stock of his parents to our museum. Ironically, he received more money for it than what was paid in 1963 for the complete stock. Of course that is a misleading comparison, because inflation is not taken into account. On that special occasion Van Eskert was kind enough to hand over the original invoices of the pipes. These seven rare payment receipts made it possible, together with my personal experiences of the Mrs. Van Eskert era, to put the sale of the pipe warehouse in writing. These accounts are the most recent source in the price distinction at Goedewaagen at the time of the clearance sale. They also make it possible to calculate the tremendous profits realized by Van Eskert with their pipe trade. In 27 years trading with an investment of less than 2,400 guilders, a turnover of more than 45 thousand guilders was realized!

More important is that the purchase meant a lot for the appreciation of the Goedewaagen pipe. You can say that the couple Van Eskert experienced a well-paid hobby at the clay pipes, that gave them a lot of pleasure. It is thanks to their activity that the clay pipe by Goedewaagen has gained so much appreciation, only possible since they are still available for collectors and enthusiasts. This in full contrast to all other Gouda pipe factories.

© Don Duco, Amsterdam Pipe Museum, Amsterdam – the Netherlands, 2013

Illustrations

- Invoice for clay pipes from Koninklijke Goedewaagen to the firm Van Eskert in Haarlem. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, 1963.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - Factory building of the firm P. Goedewaagen on Raam in Gouda before 1909.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - Clay pipe with portrait of the sultan of Zanzibar from the stock of P. Goedewaagen & Sons. Production Saint-Omer, Firm E. Duméril E. Bouveur, 1865-1880.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 14.292 - Ware house for pipes of the firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons on Jaagpad in Gouda, c. 1912.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - Clay pipe with handwritten shape number in the bowl. Gouda, firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 192, 1890-1910.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 14.175 - Selected range of clay pipes by Koninklijke Goedewaagen. Gouda, 1958-1961

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 6.223b - Photo of the pipe panel by Cornelis Römer. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, c. 1958.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.253 - Facade of the tobacco shop Van Eskert on Houtplein. Haarlem, c. 1960.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - The so-called large collection of clay pipes in the tobacco shop Van Eskert in Haarlem.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - Clay pipe with on the stem embossed Peter Dorni. Gouda, firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 304, 1890-1910.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 3.954d - Clay pipe "shoe polisher" with multi coloured glaze, one of the more luxurious pipes from the purchase of Van Eskert. Koninklijke Goedewaagen, shape 756, 1914-1918.

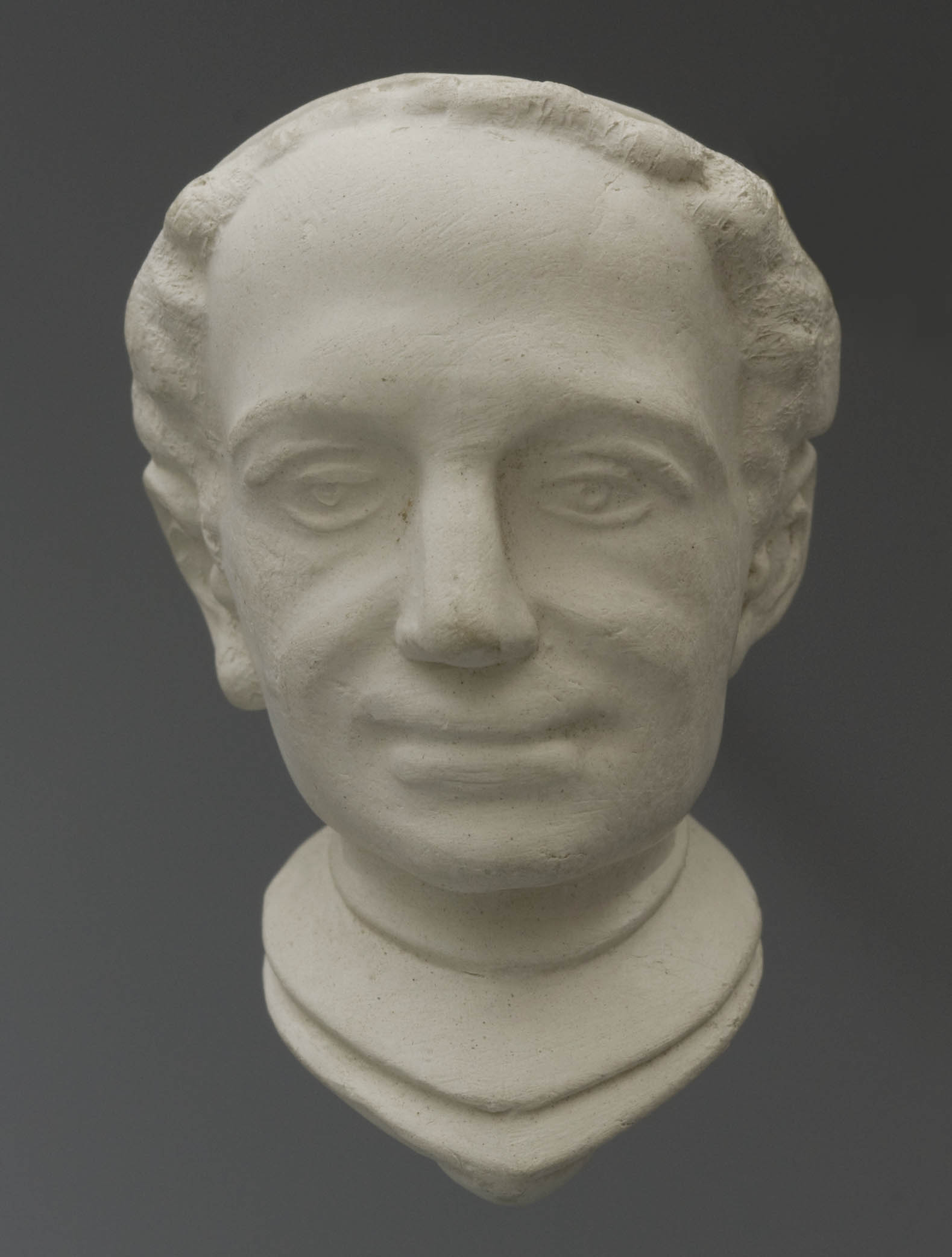

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 5.263b - Clay pipe with bust of Pope Leo XIII. Gouda, firm P. Goedewaagen & Zoon, shape 320, 1895-1905.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 8.167a - Clay pipe with the portrait of Peter Stuijvesant. Gouda, firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 617, 1900-1915.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 8.658 - Clay pipe with portrait of Lou Caddetou. Southern France, c. 1910, later sold by P. Goedewaagen & Sons, Gouda, 1910-1940.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 5.379b - Shield with a collection of clay pipes as sold by Van Eskert. Haarlem, 1977.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - Picture of a collection of clay pipes auctioned at Mak van Waay in Amsterdam, 1978.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum documentation - Press mould for overlong clay pipe with Mercury and Neptune as decoration on the bowl. Gouda, Pieter Goedewaagen and successors, 1867-1963.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 9.467

Literature

Don Duco, Verzamelaars en hun passie, chapter: Een fabrieksvoorraad als verzameling, Amsterdam, 2010.

D.H. Duco, Bronnen tot de geschiedenis van de pijpennijverheid in Nederland, Amsterdam, 1976 a.f., 29-07-2000.