Tobacco pipes from the Xhosa, from traditional utensil to souvenir item

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

De Xhosa-pijp, van traditioneel voorwerp naar reissouvenir

Année de publication:

2013

Éditeur:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Description :

The story behind the characteristic wooden Xhosa tobacco pipe based on objects from the Amsterdam Pipe Museum.

In the Eastern Cape of South-Africa, the Xhosa people have found their homeland there after wandering around. Travellers who visited this area in the past were confronted with smoking men and women, often sitting in a circle. It is not surprising that such meetings had a sacred aura and spoke to the imagination of Europeans. Travellers became intrigued and bought a Xhosa pipe as a souvenir. The Xhosa tribe soon discovered the economic benefits of their tobacco pipes and gradually created specimens with a tourist design or with colourful beadwork. So the simple Xhosa pipe with its straight wooden stem and metal inner bowl turned into a product adapted to the taste of the European for whom a pipe became an original gift item for the homeland. The people themselves continued to use simple wooden pipes, although in addition a culture of luxury smoking pipes developed. This article presents the variation within this typical Xhosa pipe using examples from the collection from the Amsterdam Pipe Museum.

Briefly about the people

The Xhosa, who call themselves Amaxhosa, are part of the Bantu people who jointly populate the southern half of the African continent. Already before 1500 the Xhosa wandered from East Africa to South Africa and penetrated far into the area that was traditionally inhabited by the San and the Khoikhoi. The latter two tribes were previously known to us as Bushmen and Hottentots, while the widely used word Kaffer was used for all tribes. The homeland of the Xhosa then became the area north and east of the Cape, roughly between Cape Town and current Lesotho. Although the three peoples retained their own identity, the Xhosa took over the typical click and sucking sounds from the Khoikhian language. Both peoples lived from livestock farming, in contrast to the San who were hunters and collectors.

After incidental visits by the Portuguese, the Cape became an important post for the VOC from 1652 onwards. Dutch VOC ships stayed in the Tafelbaai (Table Bay) for a few weeks to take in water and fresh food before continuing to the Indies or back to the homeland. Gradually, the land behind Tafelberg (Table Mountain) was taken into use by a growing group of Dutch settlers for horticulture and arable farming. This included the cultivation of tobacco. Unlike in the other VOC offices, civil servants and farmers were allowed to settle with their families in the Cape as so-called free citizens. This created a prosperous agricultural area. However, the Western Cape was not a formal colony.

Gradually the original inhabitants were driven further north and east with their cattle, but not so far that they could continue to sell their cattle to the colonists. In practice at the end of the eighteenth century some 6,000 Dutch, about the same number of Germans and 2,500 French lived relatively peacefully together with slaves from India and West Africa and with the original tribes: the Khoikhoi and the Xhosa. A large proportion of the Khoikhoi, however, was killed in the smallpox epidemic of 1712; the survivors gradually lost their tribal bond and with it their own culture. The Xhosa moved eastwards, as more European farmers settled in the Cape area.

When the British took over the Cape around 1800, they introduced colonial rule over all tribes, including the whites. The non-English settlers, also called Afrikaners or Boeren, wished to avoid the British authority and withdrew from 1830 to the east and north. They are known as the trekboers (Voortrekkers). The British mainly extended their colony to the east. This led to as many as nine border wars in the Eastern Cape, also known as the Xhosa wars. During these disputes, the Xhosa tribe was pushed further and further eastward over the river Kei, the so-called Transkei. This Transkei eventually became the Xhosa area and remained almost entirely in the hands of the Xhosa until well after 1900. Even now there are few white people. In the Ciskei, the area west of the Kei river, most English settlers did not want to live as solitary farmers but grouped in a few cities. To exploit the area anyway, the British administration attracted German colonists from 1850 onwards.

Tobacco and smoking at the Xhosa

Following the history of the people, here some information about the role of tobacco and smoking in South Africa. It is generally claimed that from 1652 the Dutch settlers imported tobacco into the Western Cape and smoked from imported clay pipes. More likely, however, is that the Portuguese have already brought the tobacco around 1600, though the evidence is lacking. It is certain that the Dutch settlers immediately started growing tobacco as one of their crops and use this as a means of exchange with the Khoikhoi. This group is soon known as dedicated smokers. A travel report from 1673 reports that both men, women and children smoke.

In addition to tobacco smoking, consumption of hemp is known throughout the South African region. This has been spread by Arab traders via the African East Coast. Initially hemp is pulverized and drunk mixed with water. Smoking is only done when the pipe smoking becomes known. First hemp is added as an addition of tobacco, later pure hemp is smoked. The hemp smoking is generally known under the name dagga, mainly in water pipes because the water cools the much hotter smoke, improving the taste.

When tobacco smoking is introduced at the Xhosa, it is not known. The oldest mention of smoking Xhosa dates from 1727 and it appears male and female, young and old smoke. The use of the Xhosa to circulate the tobacco pipe comes from dagga smoking. So there is a mix of local customs and influences from the Arab world, while Dutch tobacco smoking culture has penetrated only to a limited extent. Little is known about the development of the tobacco pipes. Alternatively, there is also the sniffing of powdered tobacco leaves.

Among the Xhosa smoking tobacco became a social affair and takes an almost ritual place. When men smoke together, the pipe goes round the circle. That may be in the corral for the own hut with some tribesmen, but also in the market place where they sit in a large circle, leaning on their own club, passing the burning pipe. Surprisingly, every smoker has his own, usually wooden mouthpiece that is placed on the pipe. That use is not rooted in the sense of hygiene but is against bewitching. For the Xhosa the mouthpiece contains something of the mind of the smoker and it is undesirable if this would end up with a malicious one.

Besides men, the women of the Xhosa smoke equally intensively. For women, owning a pipe is even more common, while the stems of the women's pipes are usually longer. Travel reports from the beginning of the twentieth century tell how women feed their babies while smoking a long-stemmed pipe. Nothing has changed here since the eighteenth century. They share the daily news with others while smoking. Smoking gives them energy and when the children are about six months old, they sometimes let them suck on the pipe stem to get them to rest. The long stems have been chosen from a sense of status rather than a practical consideration. The idea that these long stems keep the smoke away from the babies is typically European.

The Xhosa smoke the local tobacco grown in the Transkei. Tobacco is generally available here, although most smokers choose to grow it themselves. The men take care of this and maintain a small tobacco field behind their hut. The harvest has traditionally been dried and then preserved as spun tobacco. It is also used to exchange goods. The mixing of tobacco with marijuana is common to the Zulu people but hardly occurs with the Xhosa. Some authors strongly emphasize this, but that is not right.

Lighting of the pipe is done with glowing coal. Female smokers often pick up these coals with their fingers and shaking in the palm of the hand the fire is transferred to the bowl of the pipe on which the coal is then placed. Burning in the glowing coal sometimes leaves traces on the top of the pipe bowl. In alternative cases, the pipe is lit with a piece of smouldering wood.

Remarkably, Xhosa smokers also consume the black oily nicotine deposit from the stem of the pipe. This is removed with a grass blade which is then licked off. The Xhosa call this concentrated tobacco juice intshongo. Of course, this tar-like substance gives a violent nicotine kick, which is never achieved with normal pipe smoking. In addition, the tobacco is used as a medicine, for example as an antidote to snake bites

After the smoke ceremony, the best pipes will be stored in a leather pipe bag decorated with beads. Strangely enough, these accessories are now extremely rare and they are barely depicted in literature. In addition to smoking, in the middle of the twentieth century the smoking of brown paper cigarettes comes into use, the so-called zoll. This quickly becomes the cheapest way of tobacco consumption, the most smoked by young boys. Gradually, cigarette smoking becomes more general and causes a strong decline of traditional pipe smokers.

The choice of pipe

Among the Xhosa there is a strong relationship between the position and status of the smoker and the choice of the tobacco pipe. There is also a clear distinction between the two sexes in the smoking equipment. The tobacco pipes of the men are more varied and usually shorter in stem length. The practicality of the smoking instrument is the starting point for the working class. The choice is further determined by the type of wood and the design, although the smoke quality of the pipe is of course of the first importance. In one of the following chapters I will discuss the typical shape of the pipe.

When women choose a pipe, the stem length is the determining factor. This stem length counts as a status indicator in which older women smoke from the longest pipes. The standard length is 44 centimetres, excluding the mouthpiece. In the twentieth century, one or two centimetres are added. Girls are considered not to smoke until they become mothers and then they start with a short tobacco pipe. In practice many girls smoke and then they use a pipe with a really short stem, which they can easily hide by sticking it between their clothing folds. This is practical because they should not be seen with a tobacco pipe by the elderly.

The Khoikhoi living between the Xhosa smoke different kind of pipes, made of stone. Favourite there is serpentine stone that can be beautifully coloured, which strangely enough has never been used by the Xhosa. In terms of shape these stone Khoikhoi pipes are derived from the Gouda clay pipes and wooden pipes from the region around Ulm in Germany. Both shapes are therefore directly copied from the settlers. It is the absence of white baking pipe clay or burr walnut wood, that the Khoikhoi use serpentine stone. Such pipes are mounted with a reed or wooden stem. In addition, the Khoikhoi also use the water pipe with a stone bowl, in which they smoke a mixture of dagga and tobacco. A source from 1719 mentions that the Khoikhoi women also smoke when feeding their babies.

It is astonishing that the Xhosa and the Khoikhoi live side by side, but both have their own culture of smoking and their choice in pipes. As noted, this is reflected in the material used, in the shape of the pipe and also in the rites surrounding the smoking. Although the Xhosa only started smoking tobacco relatively late, it quickly becomes popular. The tobacco pipe is soon fully embedded in the lifestyle and gets a high standard. It is unclear where the distinctive wooden Xhosa pipe is inspired, certain is however that it takes an explicit place in their culture. For example, an unwritten law shows that in a traditional outfit one can never use a pipe other than the typical Xhosa design. The tobacco pipe has apparently become an integral part of its own tradition.

The habit of pipe smoking is so important in Xhosa culture, that when someone is deceased one uses the expression that he has laid down his pipe. In many cases the tobacco pipe was buried with the deceased. Smoking is also seen as a means to keep the spiritual world well-tuned. Some rituals are aimed at this and confirm the sacred appearance of tobacco use. In addition to the standard tobacco pipe, the Xhosa uses water pipes, the reservoir usually made of ox horns. Only when it concerns pipes for old women, a calabash is used more often as a water reservoir because it is lighter and more pleasant on the mouth.

Manufacture of pipes

The raw material for the Xhosa pipes is the hardwood of the acacia caffra. In the native language this type of wood is called umtholo, in Afrikaans gewone haakdoring. It concerns fairly hard tree wood with a specific, regular vein and a light brown colour. The most suitable is the root wood of this tree, which is harder and also slightly darker in colour. Pipes made of this root wood are more durable but also more expensive because the root wood is more difficult to shape. In addition, a second type of wood is used, the dracaena, in the local language designated umnyamanzi. This type of wood varies more in colour and is more lively with ribbing with lighter zones and a more expressive grain. It is the wood species for the more modern Xhosa pipes.

The manufacture of Xhosa pipes is male work, the Xhosa does not know female pipe makers. The production starts with picking out the tree for cutting which is already a ritual in itself. The tree is not simply cut down but it is waited until the moon sets, just before sunrise. There is another superstition when cutting. For example, if the moon shows itself during the daytime, the wood will be too moist and therefore unusable because it will split. If there is no moon to be seen during the day, it is believed that the wood will be dry.

The tree wood is first sawn into pieces suitable for pipe production, the stem length of the end product determining the length of the wood block. Then the blocks are laid to dry for about two weeks. This could be at a shelter in the forest, in other cases in the hut of the pipe maker. Each log is suitable for four pipes, two aside and two on top of each other. In this way, the log has enough thickness to prevent warping during drying. Only after drying the block is split into two planks for each two pipes. In such a plank of wood the stems run parallel, the bowls enclose the stem ends. The grain is always along with the stems as a guarantee of sufficient strength of the pipe. In this way one can deal with the wood as economically as possible.

After sawing the rough shape of the pipe, the smoke tube is made in the stem, with a diameter of three to four millimetres. Initially this flue was burned with a hot piece of iron wire, later drilling came into practice. The pipe maker has a set of drills that increase in length as the work progresses. An extra thick, conical drill is used last for the insertion of the stem end in order to be able to insert a pointed nozzle later. During drilling the pipe is clamped between the knees, later better equipped pipe makers use a vice. Usually the whole piece of wood is pierced, the hole that is formed at the lower side of the bowl wall is later closed with a piece of wood. That choice has a time-economic reason. When a pipe maker does not want to drill through the bowl, he has to be cautious and always test whether the drill has reached the right spot. That amounts to the frequent extraction of the drill to see how far one has progressed.

Then it is time to open up the bowl. For this, an ordinary chisel is used, initially homemade, later purchased from English traders. To keep the chisel sharp, a sharpening stone is always within reach. The desired bowl volume is controlled with a wooden stopper, which must fit exactly in the pipe bowl after the hollowing out. This plug or mould is called isikhonkwane and emphasizes the serial production of the Xhosa pipe.

Because the wood is fragile, it must be protected against burning. Xhosa pipes therefore have an inner shell of sheet metal. The application of the metal inner bowl is done by means of the wooden plug, where the metal is folded around. Initially tin has been used for this because it is easy to form, but soon it was switched to zinc or galvanized iron. Even canned tin can be used, sometimes the imprint on this metal can still be seen on the inside of the pipe bowl. We do not see copper as a covering for the bowl because it gives an unpleasant taste. The metal is cut and then flanged, the craftsmanship speaks mainly from the folded bowl opening of the pipe, which fits seamlessly with the wood. The new pipe has an attractive appearance with its matt brown wood colour and shiny blank metal inner bowl. In use, the wood quickly darkens as the metal oxidizes and strikes black, causing the colour contrast to disappear in a short time.

If the metal is too stiff, the bowl edge cannot be flanged, but it is cut in so that bare triangles inevitably arise on the edge. These triangles are often a reason of burn in the pipe bowl, which means that the lifespan will soon come to an end. The bowl interior always has an overlap and for this a fixed method has even been developed. The overlap is left or right of the pipe bowl, depending on whether the smoker is left or right handed. Apart from the fact that the sharp metal tip will never touch the hand of the smoker, the double piece of metal functions when lighting the pipe as a guarantee against the burning of the wood. The sheet metal does not necessarily extend to the bottom, that is to prevent the flue channel becoming blocked so that the draft in the pipe disappears. Moreover, the danger of burning the pipe at the bottom is not so great because the moisture of the tobacco is collected there.

When the pipe is ready, it will be finished. First the continuous borehole is closed, with pipes with a bent stem this is sometimes necessary in several places. For this purpose one uses plugs of the same pipe wood that fit so precisely that these boreholes become virtually invisible. Then the surface is smoothed. This is done with a knife or a piece of glass with which the saw and file traces disappear. Sandpaper is used in later times. Decorations were applied in different ways and will be discussed later.

Finally, the finished product is rubbed with animal fat that must protect the pipe against cracks by moisture and heat. That fat also turns the surface from light to medium brown, a colour that is desired for many smokers. In later times, when the majority of the pipes are produced for sale as a souvenir, this post-treatment is omitted. The pipe does not have to become stronger because it will rarely be used as a smoking instrument.

The serial, almost standardized, production process in which there is hardly any change, indicates how industrially the manufacture of Xhosa pipes has taken place. The enormous production of these tobacco pipes is also apparent from the fixed wages and prices that this industry knew. In the heyday, the prices of the pipes were directly related to the raw material and the amount of labour. The price was calculated according to stem length in whole and half fists. An old source speaks of 10 cents per fist length. When the English domination gets stronger, the price is calculated per inch, although this is the same. To a length of ten inches the pipe costs three cents per inch, after that the pipe becomes more exclusive and the price is 5 cents per inch. With the cutting and drilling of the mouthpiece, 2 cents was earned.

Many pipe makers work for their own village or region. Their products are sold as barter for a chicken or a young goat. Because the pipe maker often knows his customers, a personal element can be fitted in the pipe on request. The surplus of pipes is given to travelling traders who receive commission, including a pipe to use for themselves. Often they earn a little extra when they sell the pipes in other areas for an additional price. Information about the profit margin by the middlemen is also available. They charged 7 to 9 cents per inch, the double of the production price.

The three characteristic Xhosa pipe shapes

It is clear that the Xhosa pipes are produced in large series with a fixed design. The oldest examples handed down date from the nineteenth century and have a slightly conical bowl characterized by a slightly tapered opening (Figs. 1, 2). These bowls are called imbhiza or ipheko. The bottom is rounded and often has a heel shape or inkaba. The stem, indicated with intungo, is straight and ascending with a stem angle of about sixty degrees. This traditional pipe is known as inqawa yamadoda.

In many African countries it is customary that the pipe shape differs between men and women. This is also the case with the Xhosa where the bowl of the women's pipe is higher and narrower than that for men. The male pipe has a larger diameter so that it can contain more tobacco. The height of the traditional pipe bowl is around six centimetres. The length of the stem of the pipes has already been discussed and measures a maximum of 44 centimetres, excluding the insertion nozzle. As stated, on average female pipes are slightly longer in stem.

This standard tobacco pipe with ascending stem is the earliest Xhosa type that remains in use until the twentieth century. This develops into a bowl version with a cylindrical bowl that is almost at right angles to the straight stem and has a bowl height of up to eight centimetres (Fig. 4). The stem length here varies from fifteen to a little over 45 centimetres. It is a pipe with a more convincing silhouette although part of the former elegance has disappeared. This standard longer Xhosa pipe is indicated with umlolombela or umngcongo. When it comes to a woman's pipe one speaks of inqawa and the yabafazi. The short woman pipe is called inqawa yabantu abancinci and has a stem length between 18 and 25 centimetres; the male counterpart with the same length is called inqawa yamadoda. These more clumsy pipes become popular after 1900 and quickly dominate over the finer, most nineteenth century specimen. The rather sudden change in form cannot be explained properly.

A large number of pipes have a somewhat rounded heel that, according to European authors is a reminiscence of the Dutch clay pipe with oval bowl and heel or the English equivalent. The Xhosa, however, see the heel, indicated with inkaba, as the belly button of the pipe and with that they make a distinction with European smoking equipment. It must be said that the heel is also a feature of pipes of many other African tribes. In addition, the shape of the Xhosa pipe is not so convincingly derived from the European clay pipe as most authors believe. The heel, that is clearly not so square shaped as the Dutch, later shifts to the stem set but remains present. Even with figural pipes, this heel shape is often used as a transition marker between the bowl and the stem, but is no longer knob-shaped.

The stem end of the Xhosa pipe has a slight trumpet shape. This widening provides the desired firmness to clamp the separate insertion nozzle, a solution that has no comparison with Western European smoking equipment either. However, many African peoples use a separate nozzle from a different material because it is more durable than the pipe wood. Buffalo horn is popular with the oldest pipes, is durable and feels good. In the twentieth century, the buffalo horn is exchanged for soft wood for unclear reasons. Since 1940, the insertion nozzle has been made of clear natural wood from which the bark is scraped off, it is called umthathi. Reed is also used as a mouthpiece. The length of the mouthpiece is a personal choice of the smoker. We distinguish four lengths: ingcaphe, inxindeba, iximheya and inximbheya. The existence of four words for such a simple object as a pipe mouthpiece indicates the importance of this part in the Xhosa culture.

A new adaptation in the Xhosa pipe arises around 1920. Then both the bowl shape and the stem change. This new pipe type is called umbhekaphesheya, a name that refers to the slightly backwards leaning bowl, which is still slender and high. At the same time, the pipe stem is also modernized. It used to be provided with a trumpet-shaped cuff to clamp the separate mouthpiece, but under the influence of the European briar pipe the tip becomes an integrated part of the pipe. Without doubt, this pipe type has been copied from the European tobacco pipes, the upexe or oopexe. The target group is very specific: it is smoked by Xhosa men who work in the urban area so they come into contact with foreigners more often. Following the example of Europeans, they are looking for a more contemporary pipe shape, but are dissatisfied with European products because they tend to burn too quickly and are significantly more expensive. Equipped with a metal inner bowl, the local product is less affected by the burning tobacco. Incidentally, burning out is mainly a problem for smokers in the open air, which is often the case with the Xhosa.

Characteristic of this more modern type of pipe is also the new marking between stem and mouthpiece, in which a colourful zone of slices of shell and other material is inserted. That finish, named ünkcaza is glued with the stem. Buffalo horn is used for the mouthpiece, when the pipes are cheaper it is blackened wood. In an early type, which we can consider to be an intermediate form, the bowl is still perpendicular to the stem and the heel shape under the bowl has been extended to a rail with perforations (Fig. 6). The sturdy appearance of the pipe was retained. A somewhat later version has the characteristic inclined bowl, although it is extremely high (Fig. 7). In European pipes that was never usual, except for a short Danish vogue. This pipe has a silhouette that cannot be reconciled with any previous creation, except for a certain type of American Aztec pipe.

The evolution of the traditional Xhosa pipe of course shows more details. For example, there are changes to the design and finish with the main characteristic that the pipes almost unnoticeably lose their original characteristic of fineness, gradually becoming larger and coarser. Influenced by the flourishing trade of souvenirs, the requirements for use are reduced and the pipes become more and more a gift item, no longer meant to be smoked.

From prototype to curiosity

After explaining the three basic shapes of the traditional Xhosa pipe, a separate category deserves attention. This concerns the more artificial pipes with decorations or quirky designs, often in free geometric forms, both in the decoration of the bowl and in the course of the stem. The figural pipes also fit in this outdoor category. Although it is not inconceivable that these exceptional pipes were initially intended for personal use within the Xhosa tribe, the majority was sold as a souvenir pipe. They come to the market from 1850 onwards with increasing numbers.

Decorations on pipes are applied in two ways. The most common is engraving or cutting out simple, usually geometric patterns. These are then filled in with lead, by laying the tobacco pipe in the sand and pouring the cut out pieces with liquid tin or lead. The surplus is then cut away and rubbed with a cotton cloth. The result is a beautiful light dark effect. Geometric patterns are popular, with solar and other circular shapes dominating (Figs. 1, 2). Zigzag bands on both bowl sides are also gaining popularity (Fig. 8). Rare are representations of, for example, a hunting scene or human figures. A single decoration is provided with a year or inscription (Fig. 2).

In exceptional cases, pieces of copper or ivory are inserted. Sometimes nails are hammered, again in a geometric pattern (Fig. 9). Another effect is the use of metal bands around the bowl or stem, which are soldered or have a flange seam as is customary in several African cultures. Most of these decorations, for that matter, have a technical reason to conceal uneven areas in the surface or to strengthen thin, fragile pieces in the bowl wall or stem.

Less common is the use of metal wire in iron, brass or copper (Fig. 3) as decoration, sometimes even in an attractive colour combination. This is also meant to obscure the surface, while the braid gives the pipe a luxurious appearance at the same time. Metal braiding gives new pipes a flashy look. At the time they were equal to the beaded braid, although the durability is significantly larger. Not impossible this wicker-work was not made by the Xhosa but by the Zulu, where this technique is very general. The application of beads around the stem and bowl is a more general way of refining. This decoration is discussed in more detail later.

Especially for the tourist and traveller, the tobacco pipe is made even more beautiful than a serious smoker would require. Already in the nineteenth century a variety of wondrous and artfully cut shapes are available that underline the craftsmanship of the pipe maker and are suitable to sell as a remarkable souvenir. Very popular are pipes whose stem makes a kink, giving them a striking geometric silhouette (Figs. 8, 9). Such zigzagging stems are especially admired because one is wondering how the smoke runs. This category also includes a joyous pipe with a bowl placed backward (Fig. 10), which is however referred to as a normal use pipe for a male smoker. Another joke is carving the pipe bowl within an open circle. Sometimes they testify to skilled cutting art (Fig. 11), in other cases a less neat result is obtained by working in a hurry or in a sloppy manner (Fig. 12).

The tourist market mainly stimulates the sale of figural pipes, in which the pipe maker can fully express himself. The most coveted version shows a seated woman, sometimes also a man, with the head of the person as a stop on the bowl. Often a modest beading has been applied to such pipes, to emphasize Xhosa's love for bead dressing. By adding dark glass eyes and some paint accents, the expression of the suggested figure is stronger (Fig. 13). Even the colour of the grain of the wood plays a role in the illustrated specimen. Less general but with a greater diversity animal figures are depicted, such as a buffalo or horse. Special is a standing rooster, where the bowl of the pipe is hidden in the hull of the animal (Fig. 14).

Another category consists of figural pipes in the form of trains, a locomotive or another means of transport. They are less old and only emerge from the end of the nineteenth century. They embody elements of the modern European world. More humble and a bit bizarre are pipes with for example the image of a pocket watch or compass. All in all, the variation in figural pipes is so large that the importance of the souvenir function clearly prevails. Whether the people also smoked these pipes themselves is an unanswered question.

Original but no longer worthy of use are the multi-bowled pipes, ideally suited for tourists who do not look for a common object. A Xhosa pipe with two bowls on a single stem comes from the former collection of Alfred Dunhill (Fig. 15). This product manifest the pure Xhosa characteristics, but there is no question of true smoking comfort. It is said that one of the bowls is closed with a stop during smoking. Extremer is an example with four pipe bowls (Fig. 16), a prestige piece we acquired from the same Dunhill collection. The fact that this last pipe has not yet been finished with stoppers in the drill holes and does not have metal bowl lining, already indicates that it is not a smoking instrument. Yet this pipe is functional, proven by the smoke tube that is connected to all pipe bowls. In the tradition of the Xhosa, a pipe without metal lining is often presented as a gift to Europeans. Whether the Xhosa want to prevent the pipe from being smoked by non-tribesmen is a hypothesis.

Decorations with glass beads

Characteristic for the later period and the most luxurious appearance are tobacco pipes with braided glass beads. Strangely enough, the pipes decorated with glass beads are attributed to the Dutch. The fact that the beads have been obtained from trade relations with our country is very likely, but the adornment of pipes with glass beads is certainly not a habit that can possibly be taken over from Europe. Beadwork is rooted in African cultures, although it is an expression in itself for the tobacco pipes. The pipes decorated with beads are considerably more expensive, not only because of the material costs but mainly because of the labour involved. The women and girls who did this work were paid per inch, just like the pipe maker, and received two cents for that. The braiding of the stem decoration is quite labour-intensive. For the stringing of the beads of one fifteen-inch pipe, a full day was needed. The adornment of such a pipe eventually yielded thirty cents of wages.

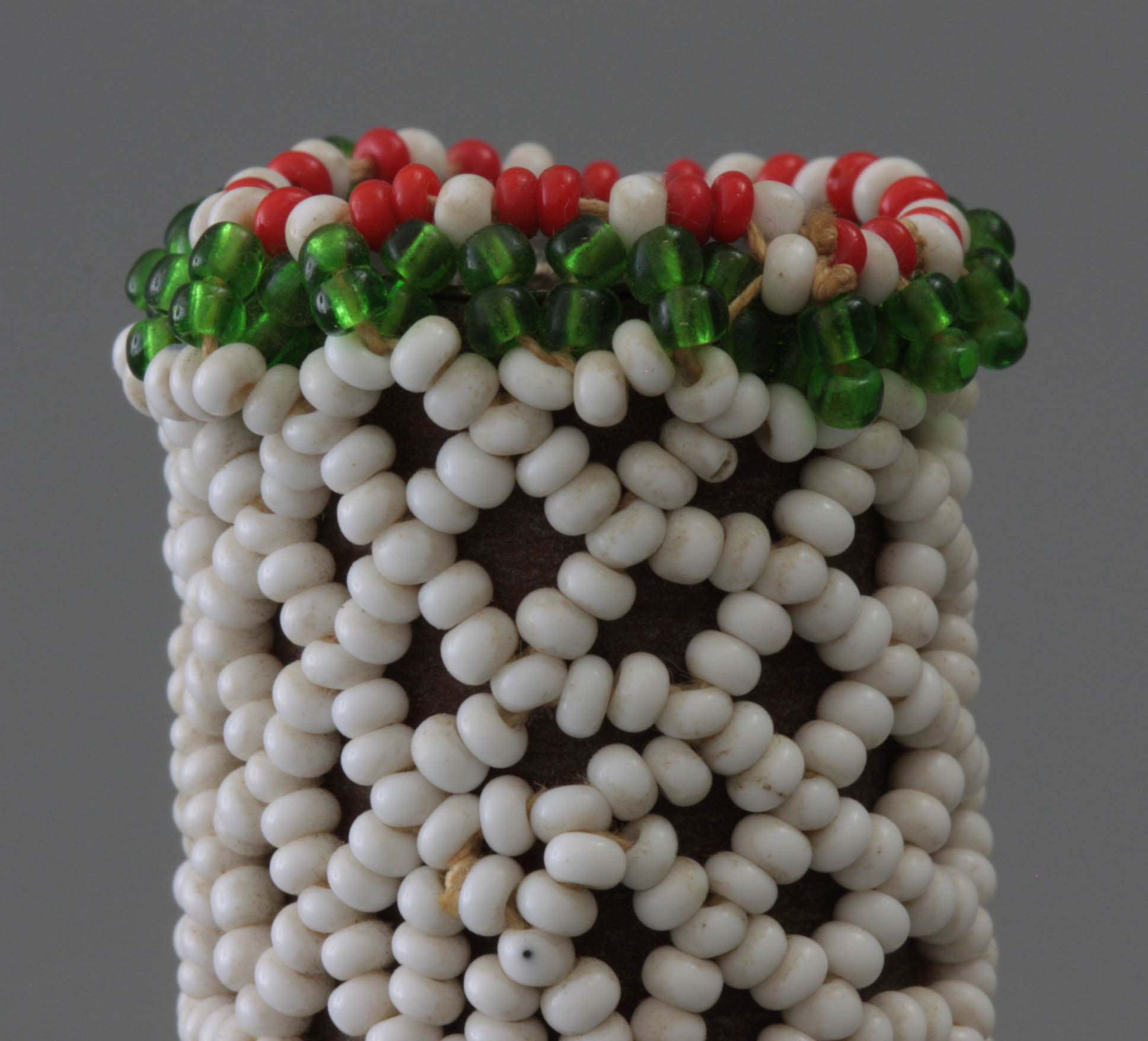

The beading is mainly focused on the stem, but more luxurious pipes are also provided with a network of glass beads around the bowl. Some pipes decorated with beads have special uses. For example, the wise man and the lady fortune teller, the isangoma, possesses a pipe decorated with beads in white on the stem. Such bead dressing stands above the status reflected by the stem length. Derived from the pipes for fortune tellers, copies intended for a headman are decorated in white beads as well, though colour accents have been added as a distinction for the status of the user (Fig. 17). To make an impression, this decoration is also arranged around the entire pipe bowl. With such a product, the carrying strap along the stem is also made more explicit.

The summit of a bead pipe is the gift of a wealthy man to his wife. He purchases a umlolombela pipe decorated with a lot of beadwork and pays the exchange value of a female goat. Such long-stemmed, expensive pipes are carried in a goatskin bag, the ingxowa yebhokhwe. A goat must also be sacrificed for the pipe bag so that such a smoke set symbolizes ultimate wealth. In this gift we can see with some imagination the equivalent of the Dutch bridegroom pipe.

Tobacco pipes decorated with beads often show a dominant colour, with three or four other colours in addition. The colours white (mohlope), turquoise (twetshe), blue (ivusi) and red (koloko) are the most common. In addition, there is a second colour blue (ibotile). Black or mnyana is of more recent date. Other colours are characteristic for the period after 1950. As far as we know, the geometric bead patterns does not have a deeper meaning. However, the method of decorating with beadwork underlines the rank and status of the user by letting wealth and prosperity come from the decoration. Those who do not live in prosperity are smoking in the circle and only have their own mouthpieces.

A bead chain to carry the tobacco pipe is often included in the braid, sometimes even supplemented with a strap to prevent the separate mouthpiece from getting lost. A nice example of two later products from the former Douwe Egberts collection are equipped with such long support cords that underline the souvenir function of the tobacco pipe (Figs. 19, 20). They were purchased before 1975 from the Ndebele tribe of the Xhosa. Incidentally, at the same time as an undecorated copy (Fig. 5), which shows the contrast with the ordinary pipe. Witnessing the lack of oil treatment, none of these three pipes were intended for use, a fact that has not changed ever since.

As far as the beading is concerned, the length of the pipe expresses the age of the smoker, the wealth and status can be concluded from the added characteristics. The morality of the people ensures that the unwritten laws are strictly observed. Smokers always certify that their pipe matches their personal status. It was considered inappropriate and inadmissible to violate these rules.

Epilogue

Nowadays, the Xhosa pipe is far from extinct. As a souvenir item it has become so well known that the pipe is still being produced to be offered to travellers. In this process, only the sturdy straight model maintained, now provided with time-specific features. So nowadays there are even very short pipes, never used in the past. They are ideally suited for the luggage of the foreign tourist.

As has happened in the past two centuries, the traditional pipe production of the Xhosa is still changing. Inevitably, the products gradually lose their own characteristics, incorporating new features. Since the modern West European briar pipe is also popular with the pipe smoker in South Africa, especially with the city dweller, that design is gradually taken over. Some established Xhosa pipe makers produce pipes in the briar shape, but then according to local tradition (Fig. 21). The pipe wood is unchanged, including the metal inner bowl. You can call them a bad copy, but on the other hand they are also a unique expressions of the meeting of two cultures. A South African pipe in a Western form or a Western-looking pipe made in a South African tradition. Shared heritage of the late twentieth and twenty-first century. We will see how this trend will develop in the future.

With this article, the Xhosa pipe has been mapped in outline. The smoking habit, the tobacco pipe including the production method, the shape change and the adornment were discussed. Presenting a chronology in form and decoration was no easy task. We must admit, this is a typical wish for the art historian who works within Western European museum discipline. Problem in presenting such fine-meshed patterns is the lack of fixed knowledge. A characteristic feature of Western collections is that the purchase information of preserved objects has been lost at many museums. In other cases it has even never been documented. Material that circulates in trade is usually without any further information at all. As a result, they have become isolated objects that are now attributed to a certain tribe or region and are given a date without having absolute certainty.

As with the majority of the ethnographic objects, we are therefore lacking hard data of time and place, with comparable benchmarks, whereby products can be linked to maker, location and date. Perhaps this is less opportune in the more cyclical world of thought common in Africa than in the linear, development-oriented Western world. In addition, the distribution area of the Xhosa is too wide, the migration and assimilation with other tribes too large to arrive at a well-defined typology. There are dozens of sub tribes with their own characteristics and merits that are reflected in the tobacco pipe and that could thus be interpreted. This requires more objects and additional research. For the time being, we have to do with this preliminary inventory.

© Don Duco, Amsterdam Pipe Museum, Amsterdam – the Netherlands, 2013.

Illustrations

- Tobacco pipe with traditional shape with heel and up going stem. Bowl with lead decoration. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 2.339 - Tobacco pipe with traditional shape with heel and up going stem, stem end reinforced with lead. Lead inlays around the bowl. South Africa, Xhosa, 1870-1910.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.320 - Tobacco pipe with short stem, bowl and stem decorated with wire braiding. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1900.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.372 - Tobacco pipe with cylindrical bowl and long stem. South Africa, Xhosa, 1880-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.345 - Tobacco pipe in modern version. South Africa, Xhosa-Ndebele, 1960-1975.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 10.386 - Tobacco pipe with high bowl and stem with railing along the base, shell decoration. South Africa, Xhosa, 1930-1960.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.446 - Tobacco pipe with high bowl and rejuvenating stem with shell decoration. South Africa, Xhosa, 1940-1950.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.077 - Tobacco pipe with zigzag stem and geometric lead inlay on the bowl. South Africa, Xhosa, 1880-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.960 - Tobacco pipe with zigzag stem and steel nails on the bowl. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1910.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 16.713 - Tobacco pipe with a more complicated shape with a bowl that sits backward. South Africa, Xhosa, 1900-1930.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 20.430 - Tobacco pipe with short stem, the bowl with finely worked circular ring. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1900.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.836 - Tobacco pipe, the bowl encircled with a coarse cut circular ring. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1900.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.979 - Tobacco pipe, the bowl in the shape of a sitting female figure. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.716 - Tobacco pipe, the bowl shaped like a standing chicken or rooster. South Africa, Xhosa-Sotho, 1860-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.140 - Tobacco pipe with two bowls placed behind each other at the same stem. South Africa, Xhosa, 1880 – 1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.075 - Tobacco pipe with four bowls. South Africa, Xhosa, 1860-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.074 - Tobacco pipe for a tribal chief with exuberant bead decoration and with a strap. South Africa, Xhosa, 1930-1940.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.076 - Tobacco pipe with bead decoration on the stem and carrying strap. South Africa, Xhosa, 1940-1950.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 19.737 - Tobacco pipe for the souvenir trade with exuberant bead decoration and with a long chain. South Africa, Xhosa-Ndebele, 1960-1975.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 3.788 - Tobacco pipe for the souvenir trade with exuberant bead decoration and with a long chain. South Africa, Xhosa-Ndebele, 1960-1975.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.384 - Tobacco pipe with shape copied from the European briar pipe. South Africa, Xhosa, 1955-1965.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.887

Literature

Trevor Barton, 'Ethnographia described: The Xhosa Pipes of the Transkei - Cape Province - South Africa', Le Livre de la Pipe 1995 , 1994, pp 26-30.

Vinc. Zanozolo Gitywa, 'The Making of Pipes', Fort Hare Papers, 5 (2), 1971, pp 130-137.

Hooper, 'Some Nguni crafts: wood-carving', Annals of the South African Museum, LXX/3, 1981, pp 185-192

Shaw, 'Native Pipes and Smoking in South-Africa', Annals of the South African Museum, 24, 1938, pp 277-302.