The presentation of clay pipes in the Gouda museums over seventy years

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Zeventig jaar Goudse pijpen in de Goudse musea

Année de publication:

2008

Éditeur:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description :

The history of the Pipe and Pottery Museum "De Moriaan" from before the start to this century.

Abstract: At the occasion of the sixth centenary of Gouda as town in 1874 an exhibition was held that lead to the founding of a city museum. In the presentation also attention was paid to the history of the local pipe industry, famous in Holland and the world. Among the first items the former Gouda guild possessions were exhibited. This article describes the attention being paid to the history of the pipe industry including the forming of the collection, the move from the Arti Legi building to the beautiful Moriaan Museum on Westhaven. It deals with its respective directors and curators such as Bert Helbers, Jan Schouten, Josine de Bruyn Kops and Nicolette Sluijter. Also it describes the exhibits in course of the years and the attention that was given to the collection of clay tobacco pipes. As museum De Moriaan was finally transformed into a pharmaceutical museum, the pipes being brought to the city museum on Oosthaven, once a hospital known as Het Catharina Gasthuis, now named museumgoudA.

This year it is seventy years ago that a specialized museum for pipes, pottery and tiles opened in Gouda. The museum was established in 1938 in a beautiful historic building on the Westhaven in Gouda, traditionally named De Moriaan (The Blackamor). In mid-July of the past year, the local Gouda newspaper headlined that the new pipe presentation in Gouda was opened (Fig. 1) (note 1). An exhibition that was no longer housed in the familiar building on the Westhaven, but now in the main city museum Het Catharina Gasthuis. A visit to the new presentation is a reason to look back on seventy years of pipes presentation in Gouda. A reflection over past decades in which changes succeeded one another faster and faster. In this article the collection line is followed and the various presentations are discussed, always in the light of the management and their personal interest. In all; it describes the interest in a main industry in a provincial town and the way in which the museum staff presents this history to the public.

History

Interest in the history of Gouda seems to have been born at the moment the city wanted to celebrate its six hundredth birthday. In 1872, with a view to the celebration of the sixth centenary of their city rights, the plan was created to organize an exhibition of highlights from the history of Gouda. It appears that an man named J.J. Bertelman is the executive force behind this initiative (note 2). The exhibition entitled Goudsche Oudheden proves to be a great success, although critics write that a longer preparation could certainly have led to a better result. However, there is no one to complain about the flow of interested parties. Every day between eighty and two hundred people visited the exhibition which is held in the Gouda drawing school on the Markt (Market), better known as Arti Legi.

A register of this exhibition has been preserved, listing what was exhibited. As far as the pipe industry is concerned, this involves a limited number of objects: printed regulations, a few yearbooks containing name lists of pipe manufacturers, other documents and, of course, a number of pipes. Obviously the insignia of the pipe makers' guild were among the exhibits. The former guild board, which was now called commissioners, had willingly lent the silver guild plates, the guild chest and the wooden board with trademarks (note 3). Although the manufacturers at that time still owned an incredible amount of historical material, for example at the companies Jan Prince & Cie, and especially at P. van der Want Gzn., the presentation is therefore rather limited. However, we must keep in mind that the clay pipe, read Gouda pipe, was still available in a wide range in that period and that is why it was not necessary to show these products.

After the celebration, the exhibition committee concludes that it is time to found a Muzeum van Oudheeden (Museum of Antiquities), This initiative would stimulate interest in local history but should also lead to a better structured collection of artefacts. The Arti Legi building on the Markt in Gouda appears suitable for this purpose (note 4). In the years to follow, the collection gradually expanded into a curiosity cabinet. The acquisitions include all kinds of objects that donors thought to be of historical value, although many items hardly had any relation with the history of the city. In the nineteenth century the collection policy had not yet been developed: the museum commission accepted every donation to the new museum with gratitude.

In the section of the Gouda pipe industry the collection is initially very limited. Among the earliest recorded gifts, a commemorative pipe for the Pacification of Ghent in 1876 was there, produced by the Van der Want factory (note 5). After some wrangling with the commissioners of the former pipe guild, the most important historical objects of the Gouda pipe makers' guild are also housed in the museum, albeit on loan (note 6). However, the trademark board and the guild chest remain in De Harmonie, because the rulers of the former guild still meet there (note 7). These objects were not transferred to the museum until 1911 (note 8).

The start of the Gouda museum was also the work of Mr. Bertelman. This teacher in the drawing school not only traced the objects, but also took care of refurbishing and exhibiting. Thanks to his efforts, the museum opens on 12 May 1874, not coincidentally two days before the silver jubilee of King William III. For the Gouda inhabitants that meant a few days off to celebrate and those who were interested could visit the new museum.

Bertelman remains active for the museum. He was able to keep many loans, among others, the precious silver guild shields. In 1875, a special display cabinet was made at the request of the guild board, in which the collection of old pipes was also placed (note 9). The care and dedication of Bertelman is also apparent from the decision to keep an inventory book, which gives us now a sharp insight in the formation of the collection from that time on (note 10). In the field of the clay pipe industry, only one or a few objects per year are mentioned. Clearly there is no serious collection policy, the museum commission accepted what was offered or what came on their path. Among the regular donators we find pipe manufacturer C.J. C. Prince who, even until his death, has a seat on the committee for the Stedelijk Museum (note 11). Every now and then he supplies objects, sometimes pipes, but also antique glasses and other objects. After his death in 1897, his role was taken over by competitor Pieter Goedewaagen. It often seems that the committee members donated the museum objects which had become redundant in their own home or factory. Incidentally, this applies more to Goedewaagen than to Prince.

The first purchase for the pipe collection will not take place until 1886 with the famous goblet of Bastiaan Overwesel. The price for this piece was NLG 7.50 and was strongly related to the personal interest of advisor and collector Jan Prince, a glass collector himself. Afterwards it took years before another pipe or other historical object related to the pipe industry was purchased. It is clear that the budget of the museum during that period was almost zero which stood in the way of purchases. The fact that it was a part-time job or actually a honorary job for everyone involved, made sure it was not that professional.

Between 1900 and the times of economic crisis, the history of the museum is rather obscure. The inventory book is virtually the only source and it seems that the collection was dormant. The city museum is also hardly praised in the newspapers. In the thirties, this was changed by the decision to open a new museum and to exchange the Arti Legi building for the Catharina Gasthuis.

The Helbers phase

In 1920, the municipality of Gouda purchased De Moriaan building, including a part of the original shop inventory, to transfer this building into a museum in the near future (note 12). This canal house located on the picturesque Westhaven has an enchanting facade from 1617 with sculpture by Gregorius Cool (Fig. 2). Inside, it still has an authentic layout with a beautiful traditional Dutch interior and it is believed that this building would be particularly suitable for the presentation of the industrial history of Gouda. However, the municipality usually acts slow. It was not until 1931 that the restoration of the building started, initially to house the collections of ceramics and pipes - together with the Vereeniging voor Vreemdelingenverkeer (Tourist Board) (note 13). For various reasons, it will take until 1938 before the museum becomes accessible to the public.

The layout of the building is characteristic for the Dutch living culture from the seventeenth century. On the street level we find the high store that served for a long time as tobacco shop. A small room behind the left window, the so-called comptoir was the place where the shopkeeper kept his administration. Behind the store are two rooms, the so-called binnenkamer (interior room) and behind the somewhat larger sael (main room). A corridor runs to the left, in which a kitchen is separated at the back. Halfway the corridor you an oak spiral staircase leads to the first floor that has two levels. The front room above the store can be reached by a few steps, behind this are two lower floors, the upper one being called the kerf zolder (loft for cutting tobacco). The tobacco machine was traditionally used here, a device for cutting fresh tobacco leaves. Finally, there is a beautiful attic hood, under which storage used to take place.

In order to make the building suitable as a museum, all kinds of small and large changes have to be made, which are carried out under the direction of curator Bert Helbers. From his diaries we read the work that was needed before it was possible to open the museum. Those who now visit De Moriaan are immediately impressed by the magnificent layout and historical details of this traditional Dutch house. However, at the moment that Helbers started the situation looked very different. Many architectural details are not as original as you would hope and were carefully reconstructed by carpenter Van Harten. For example, a beautiful but much too conspicuous fireplace in the inner room is being relocated from the former orphanage house. Also the floors are laid new: tiles in one, in the back room a beautiful floor of marble. In the same room, a historic fireplace and beautiful carved doorposts are also installed. Originally, these rich details were not present. The building must have been extremely austere internally.

To make the museum presentation attractive, it is decided to give it the atmosphere of a nineteenth-century tobacco shop, a shop cabinet with shelves is reconstructed against the wall. This is filled with snuff tobacco jars, kegs and a few colourful tea tins. The two rooms in the back were furnished as living rooms and here Helbers covers the walls with different types of showcases. In these cabinets and cupboards collections of pipes of various kind are displayed. It involves meerschaum cigar holders, pipes made of wood, bone and stone, but there is also a display case with smoking equipment from the near and far east. Between the smoking instruments all kinds of curious tobacco related objects are placed.

The theme of the sael is the history of the pipe and the pottery industry in Gouda. Here, too, the atmosphere is between an antiquity room and a cabinet of curiosities. A variety of objects can be seen in the different showcases and cabinets without any system or chronology. The focus lies on the pipes themselves, but we also find objects relating the guild of the Gouda pipe makers. The local pottery production is less extensive. The potters guild chest can be seen here, but there is no more exhibited than a series of miniature pottery made in Gouda and a variety of historical ceramics. What was initially not exhibited is the famous Gouda painted pottery, which was too recent of date to be on display. At that time, the term Gouda pottery refers only to Gouda coarse pottery or consumer goods.

Because there is significantly more space for the pipe presentation in De Moriaan than in Arti, more can be shown. Helbers will therefore look for suitable supplements in the same way as Bertelman did more than sixty years earlier. The most important collection he acquires is the collection of J. de Sonneville from The Hague, which consisted mainly of ethnographic pipes. This collection is donated in 1939. Furthermore, all kinds of objects are taken on loan, such as countless porcelain pipe bowls from the collections of John Brasem and Van Leeuwen (note 14).

During the period of establishment, the existing pipe factories and potteries will be informed of the initiative and encouraged to donate historical objects to the new museum. It is the first time that the museum approaches the industry to make a contribution. The response is above expectations. In February 1938 the companies P. van der Want Gzn., P.J. van der Want Azn. and Goedewaagen donate modest collections of pottery. The companies Zwartjes and Van der Kist also enrich the museum with a number of objects. In the Goudsche Courant the manufacturers are thanked for their contributions (note 15). At the same time, the firm P.J. van der Want Azn. loans the oldest item from the Gouda pipe makers guild, the wooden carrying board with pipe makers marks.

The opening takes place in the late summer of 1938 and the interest is encouraging because in that year 1003 people visit De Moriaan museum (note 16). Once it has been set up, the museum remains as it is, even though Helbers does not reduce the activity of looking for further expansion of the collection. This has the inevitable consequence that acquisitions are placed in the existing presentation and it quickly becomes overloaded. After ten years of collecting, the inventory is over full and plans are made to include the first floor of the house for exhibition.

With the occupation by the Germans in May 1940, the museum temporarily closes. A number of masterpieces are removed due to the war conditions and accommodated in bank vaults. In August 1940 De Moriaan was opened to the public again (note 17). Because the most important objects remain stored, Helbers has made all sorts of changes in the set-up, mainly intended to fill in the empty places. The press extensively writes about the reopening and especially praises the novelties, supplemented by historical backgrounds. Evidently, this information has been recorded from the mouth of the enthusiastic curator, because the knowledge shows in any way of the delighted dilettantism of the curator who knew how to play the press well. For example, we learn that the French only make clay pipes and that, thanks to the retrieval of nineteenth-century moulds in a Gouda estate, it has now been proven that richly decorated pipes have been made in Gouda (note 18).

The same article describes how difficult the task of Helbers is because he should not only show the objects in its historic value but also maintain the homely character of the historic building. However, Helbers was the right man for this commission. Even those who visited him years after his retirement could be amazed by the atmospheric design of his modern care apartment, where eighteenth-century doors and other building elements were effortlessly inserted. In the same period the other city museum remains closed. This mention refers to the Catharina Gasthuis because the Arti Legi building was closed shortly before the war and the city museum would reopen in the former city hospital.

Also from other newspaper articles it appears that Helbers is a hard worker with a broad interest in art and crafts, an enthusiastic man with a great commitment and contacts in all Gouda ranks. But Helbers is not only gathering and setting up. Together with Dirk Goedewaagen he wrote a monograph about the Gouda pipe in those first years of war. Despite the war conditions, this book was published in 1942 and objects from the museum collection form the basis for this. In the years that followed, he continues to interest the press for his work (note 19). When the threat of war is finally over, the museum objects are taken back from vaults and the presentation is once again complete (note 20).

Collection policy from the inventory book

Thanks to the preserved register of incoming and outgoing objects, we know what the collection policy was focused on in the first half of the twentieth century. It is clear that even at that period there was no structured collection, while purchasing was only negotiable with authoritative objects. The wait and see attitude that existed from 1872 is still decisive: people accepted what was brought in and in fact the donators determined the direction of the collection. In other cases, the offer of merchants or private individuals was apparently arbitrary. Yet Helbers looked at it from the existing collection, filling in sub-areas and keeping his eyes open for spectacular expansions. As far as the pipes are concerned, however, there was hardly any score. The old factories had since been closed down and the majority of the material got lost.

However, warm ties with the Koninklijke Goedewaagen factory were maintained, partly due to the friendship between Helbers and Dirk Goedewaagen. The factory often donated money for purchases or brought in historical items from their own property. For example, the firm donated a beautiful sample collection of hundreds of clay pipes from their factory. This group became a wondrous sample in the pipe collection because there was virtually no material available from the other Gouda factories. Because the friendship between the curator and the factory director was visible in the exhibition, the relationship with the two other companies Van der Want was significantly cooler. When company P.J. van der Want Azn. at the beginning of the 1950s donated original pipe packaging to the museum and this purchase were not hung a problem rose. Dirk Goedewaagen, then a member of the museum committee, said he would have been opposed to exhibiting the pipe brands of the competitor. In 1953, this led to a conflict that escalated in the recall of the oldest trademark board of the pipe makers' guild that had been on loan since 1938.

In the Netherlands there was an increasing interest in pipes and tobacco in those years. Especially the folklore and the wide variety of rarities stimulated collectors. Collections were brought together by various individuals, of which the museum hardly knew. In the 1940s, for example, Georg Brongers was already actively gathering. The museum was not present at specialized auctions, such as Van Huffel in Utrecht, and even the special collections such as Van der Hoef in Zeist were not known. When this illustrious collector visited the Gouda museum, he was particularly disappointed about the variety and quality of the municipal collection.

In part, all of these collection problems are due to a lack of money and a too broad collection area both the museums. In the end, the Gouda pipe was only one aspect of De Moriaan, which also included pottery and tiles. In addition, the large Stedelijk Museum Catharina Gasthuis on the other side of the canal focussed on art and history. Because of lack of time and money, they did not take up countless offers, such as the invitation to buy a sign of a merchant in pipe clay (note 21). By the time the display cabinets are full and even the plastered walls are embellished on many spots with remarkable pipes and other curiosities, the collection lust seems to have been killed. Quality improvement is an aspect that hardly ever existed at that time.

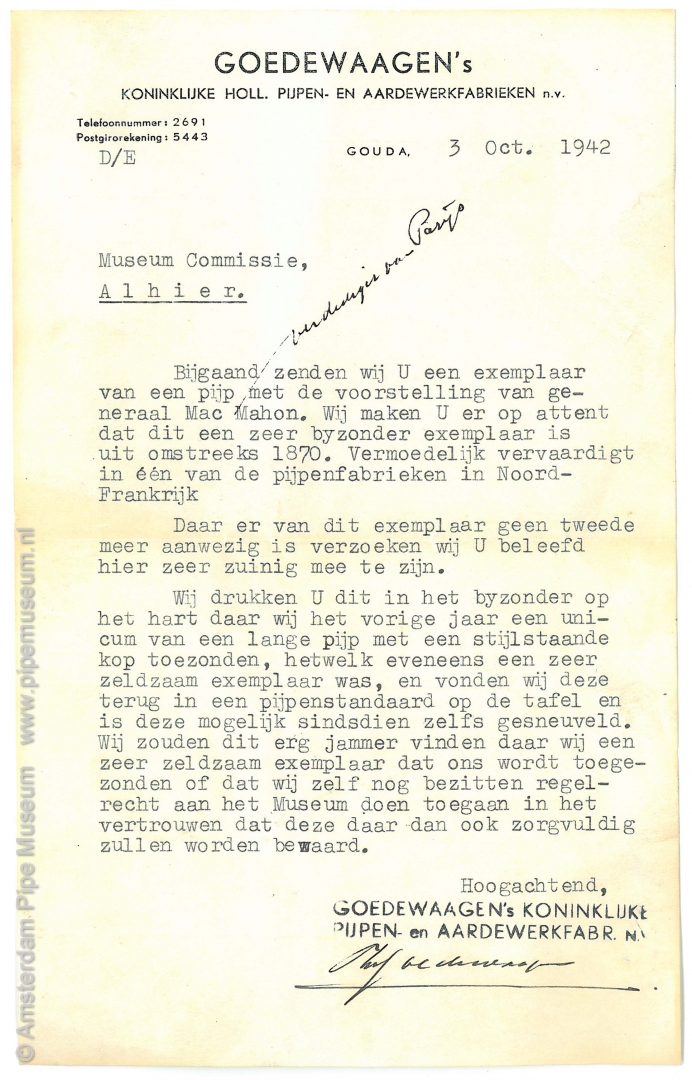

It is clear that in the thirties and forties the museum discipline was by no means established. From my conversations with Helbers, I remember his enthusiasm and his dedication, but from a scientific background the museum was completely devoid. It was about the display and the wonder, the expression "don’t you like " overrun at Helbers the level of knowledge. Even with the management of the objects it was not always so strict, as is evident from a letter from committee member Goedewaagen (Fig. 3). When he donated a special figural pipe, he makes a fierce remark about a previously donated clay pipe that, according to the donor, would not be well managed and might even have been broken.

In 1948 the necessary additional renovation takes place. Then the upper floors of De Moriaan are taken care of. The first educational presentation is on the peat loft. The focus is on the already mentioned immense carving machine, which originally belonged to this building. In one corner a potter's wheel is set up complete with some fresh pots and pans, on the other side the workbench of the pipe maker is placed. Unfortunately, the latter is not original but a poor reconstruction with a work level at completely incorrect height. Not long after that the attic is also finished for exhibition housing an overview of contemporary Gouda pottery. From that moment on the visitor could view the entire building, except for the two rooms that were still occupied by the couple Binnendijk.

Unlike with the pipe collection, there were still opportunities to collect Dutch wall tiles. In 1953, for example, the famous tile tableau with the standing rooster was purchased (note 22). Even more authoritative was the purchase of the impressive tableau of the De Swaen pottery, representing De Eendracht (Unity). These beautiful tableaux get a place in the front room on the first floor.

Helbers remained active until the 1950s, but from 1943 onwards he focused more strongly on the restoration and furnishing of the former Catharina Gasthuis as an city museum. In his diaries we find the story about the renovation and layout and between the lines we read his great enthusiasm and his great physical commitment and involvement in all those changes. He will be the last director to actually roll up his sleeves. In 1953 Helbers exchanges his position for the post of director of the Provinciaal Museum van Drenthe in Assen. In that period De Moriaan attracted more than two thousand visitors a year, which is slightly less than a third of the visit to the city museum Het Catharina Gasthuis (note 23).

A new director

The function of Helbers is taken by Schouten in 1957, doctor Jan Schouten, a versatile person. Mayor James prefers him to countless other candidates including publicist and tobacco collector Georg Brongers. Unlike Helbers, Schouten was not a director with a great stimulus for presentation; he made little change in the museums. Of course that was also part of the time, the fifties were years of reconstruction and economy. For culture and history there was minimal space and certainly hardly any budget. At that time there was still a great difference between the director who was also curator and the museum staff, the so-called bediendes (servants). The scientifically oriented Schouten was not an approachable person for the staff. Schouten manifested himself from behind his desk and there he would wear out his career, especially meritorious for the history of the city and the countless art loves that he cherished.

Director Schouten was not actively involved in expanding the museum collection and if so certainly not objects from the local industry, let alone the pipe-making industry. This is also reflected in the more-cited inventory book, the register of incoming and outgoing objects that was still being kept (note 24). In the field of the pipe industry objects were dealt with when they were offered at the museum counter, but the purchase of something high-profile does not take place. The exhibition in De Moriaan hardly changed and behind the scenes nothing was done with the objects in the reserves. The museum also received little stimulation towards the public. When I wrote a letter to the museum at the beginning of the 1970s to learn more about the pipe collection, I received the answer that the museum had a lot of material, but that it was not accessible to visitors.

In that period the management of the De Moriaan was provided by the Binnendijk couple, who lived on the first floor of the building. Visitors were able to call at set times and Mrs. then opened the door for a tour. I can still remember that first visit that I made there (Fig. 5). Sixteen-year-old boy, just fascinated by the subject, we write summer 1970. A strict lady with dark hair, stately that, and especially inexorable. When I hang up my coat and pull out a little note book to maybe write something down, she absolutely forbid that. Have a look, but do not write! The personal guided tour was an experience, albeit devoid of any historical foundation, even though I did not know much better myself.

The fact that the presentation itself and the objects shown did not have the historical perfection did not matter in that period. De Moriaan was able to pass the test in a comparison with many other Dutch museums and antiquity rooms. The professionalism of the museum as institution had hardly begun in the 1960s and 1970s. At that stage, exhibiting the objects from the past was the most important task. The educational aspect was less important than the scattering recreational character. At most museums, the collection objective had not yet been formulated and a taste focused on the ultimate objects was not yet a goal in those days. They showed the collection and that was enough.

The period of Schouten runs from 1957 to 1976, the year of his retirement. When he leaves, the situation in De Moriaan is not so different from his arrival. The renovations of Helbers and its installations were somewhat silted up, but hardly improved. The aspect of curiosity cabinet had reached its highest level. The educational factor came no further than the few cardboard cards with typed object texts whose content was often debatable. Only in the peat loft was the presentation somewhat more user-friendly. The individual visitor did not exceed the level of wonder, certainly not under the direction of Mrs. or Mr. Binnendijk. Otherwise it was with the group tours, while the visitors were pampered. Cut-to-size talks peppered with anecdotes and proverbs were exiting to experience the past. The departure of Jan Schouten almost coincides with the move of the couple Binnendijk from De Moriaan. They were the last occupants of the building. Shortly thereafter, the entire building will finally become a museum: their living room will be an exhibition, their bedroom depot.

From director to directress

In 1976 Jan Schouten is succeeded by Josine de Bruyn Kops, art historian and excellent organizer, feminist in heart and soul. For example, she is one of the co-founders of Vrouwen in de Beeldende Kunst (women in visual arts). She starts her work in the museum with a lot of enthusiasm. With her arrival the atmosphere is changing instantly. The employees get first names, there is time for consultation and dissatisfaction is negotiable. Josine quickly established her own office in the former regents' room of the hospital and leaves the now-installed curator, Mrs Loohuizen, with the administrator Van Swieten on the overcrowded administration.

From this office she runs the museum with all her charm. Meanwhile, the tasks in the Stedelijke Musea Gouda have been further divided and there are plans for expansion. The staff increases and the different sub-collections receive their own curator. Hans Vogels is the first co-curator for the Gouda pottery that had now been acquired as a historical article of national importance. For the pipes, the first person Gerrit Willems, brought in as a friend of the director, initially as an educational assistant. Thanks to his evening study, he may call himself curator after a few years. He supervised the department of ancient art, but was also assigned with the clay pipes. He did not fulfil that task with love, but it was a topic for which colleague Hans Vogels had neither time nor interest.

In June 1977 I did my first internship in Gouda. The changes were in full swing, a fresh wind blew through the enclosed spaces. Under the guidance of Josine I became acquainted with the dynamic museum company and her guidance was both thorough and versatile. From a museum perspective a grateful practical experience but also instructive to become more familiar with the collections of pipes that Schouten had amply represented. That was a big disappointment. Reading the inventory book provided clarification about the passive attitude of the museum as a collecting institution. In addition to the boxes of Goedewaagen pipes, there were bags with excavated pipes in De Moriaan's basement. There was certainly no general overview of the Gouda pipe.

One of my tasks was to organize the exhibition of visual art in addition to organizing the pipe collection. That was topical because the former bedroom of Binnendijk would be converted into a place for the spare collection of pipes. At that spot the pipes were brought together, which emerged from different attics, spaces from all kinds of cabinets and boxes. It was a first analysis of this collection area that led to the proposal to buy a group of pipes to at least complete the later period. The amount involved, 1700 guilders, however, was not available.

A visit to the Koninklijke Goedewaagen, for which I then also prepared the way and that I travelled with Josine, taught me that the collection policy was not much more structured. The factory wanted to donate a part of its historical material, especially material from the show room and press moulds. Josine only chose a few things in the field of ceramics. Director Aart Goedewaagen was insulted. In the same years, various documents, old pipes and tools came on the market from small pipe-makers and especially from former employees of Goedewaagen, without exception, finding their way to private collectors.

More than five years later, in the spring of 1983, I returned with Benedict Goes, now for two tasks. As part of the re-inventorization project that was initiated at the time, there was the extensive task of numbering and describing objects. As an internship for our study of art history, we set up this inventory and worked with maximum effort through the pipe collection. We quickly described 1,400 objects with which we got to know the collection in all its aspects. Our enthusiasm was visible, no previous trainee or employee produced such a full box with file cards of a sub collection.

As a second task we prepared the first pipe exhibition in Gouda (Fig. 6). The opening took place at the beginning of July 1983 under the title Gouda / was eens een / pijpenstad (Gouda / was once a / pipe city) (note 25). The exhibition was held in the beautifully restored Gasthuiskapelzaal and was opened by manufacturer Dirk van der Want, the seventh generation of pipe makers from father to son. It was a beautiful, transparent exhibition with attention for Gouda's main merits as a pipe city: shape development, product refinement and development of the trademark. In addition, the social aspect was depicted in three portraits of pipe makers. All in all it resulted in a special exhibition (Fig. 7). What bothered Benedict and me was that as initiator, organizers and copywriters, we received an envelope with modest content while the entire budget was wasted by the designer Marijke van de Wijst and the graphic designer Tjaard Jager. Both strived for minimalism and because of our initiative became dormant rich.

The existence of De Moriaan itself is characterized in the period of Josine's directorship by continuous political tug-of-war. As a provincial town, Gouda had too many square meters of museum and an active and therefore expensive policy in the field of contemporary art. Hence, in the treatment of the municipal budget, the plan was constantly to close De Moriaan and to house the collections in the Catharina Gasthuis (Fig. 8). The sale of the building meant the end of an eternal operating deficit and would be a lasting relief for the budget, maintenance and opening up cost a lot of money (note 26). But as is often the case in politics, one debates endlessly about the pros and cons, but the final decision is constantly postponed.

In the 1980s, however, the knowledge level in De Moriaan was still poor. The first part-time curator did not realize anything and that was not just a lack of time. For years letters with questions for answering were forwarded to the Pijpenkabinet in Leiden as a result of the pleasant contacts with Josine. The still unchanged pipe presentation remained the step-like part of De Moriaan, because several presentations of the Gouda pottery were made a few times in the upper rooms. Manufacturer Dirk van der Want, always on the breach for the history of the Gouda pipe, tried repeatedly to arouse the interest of the museum staff. One of his most daring missions was to get a fish basket that had been presented as pipes basket for years with a correct inscription. His mission went to the alderman of Gouda but remained unsuccessful.

In 1985 Josine had to resign from her duties for health reasons. In less than ten years, the museum had been transformed into a dynamic institution with an intensive exhibition policy, a beautiful new Gasthuiskapel as an exhibition space and a new modern office for staff and library. She had not only been a building pastor, but also an engaging director with great stimuli. Only that piece of forgotten history about the Gouda pipe, that had received limited attention. Although the property had been inventoried and the first major summer exhibition devoted to it, it did not become an integrated part of the museum. The incidental attention, enthusiasm and decisiveness for this had come from the Pijpenkabinet and, after completion of the assignment, became silent again.

Innovations during the fiftieth anniversary

The director's rather sudden departure caused a vacuum in continuity. New director was Nicolette Sluijter-Seijffert, in that period the preference was still for a woman as also the vacancy reported. Sluijter was installed in 1986 and was once again art historian and did a doctor’s thesis as Schouten. She came from museum Mauritshuis and saw the Gouda Stedelijke Musea as an intermediate step for returning to The Hague, but then in the role of director. That would not happen. Again the pipe industry does not have the warm interest of the director, it was a field that belonged to the city but the great art she loved had little common ground with the craftsmanship of the pipe makers of yesteryear.

At the half-centenary of the De Moriaan museum in 1988, Nicolette Sluijter is looking for an act to improve this museum. The exhibition on the ground floor of the building was hopelessly outdated and was also clogged with all sorts of irrelevant curiosities: water filters, moulds for earthenware, crates and cupboards and tableware of various plumage. In the meantime, the fresh museum had become the norm, the remainder had to be removed and transparent, educational-friendly presentations were preferred (note 27). In addition, in Gouda politics, the idea was still to abolish the museum and a refurbishment would have to stop these plans.

Nicolette visits the Pijpenkabinet, which had been based in Leiden since 1982, in order to broaden its orientation. With a view to the new plans I am asked to make a presentation of the Gouda pipe, because at that moment Gouda is painfully aware of the lead that Leiden now has. When a first set-up is made, it appears short of the collection to present the history of the Gouda clay pipe. There is a wonderful collection from Goedewaagen, but almost nothing from other companies. In addition, all sorts of excavated pipe finds had been tackled, but truly representative examples from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were virtually absent. In short, making a historical overview could only be done with loans. These gaps were filled in by the Pijpenkabinet.

Again, the new presentation had to be realized with minimal resources. The Sael was chosen as a location, which was completely emptied for the first time in fifty years. Centrally, four so-called Van Beuningen showcases were grouped, discards from museum Boymans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, but tight and neutral enough to be suitable in the historic atmosphere of the Sael (Fig. 9). Even the size and colour scheme accorded well with the space. According to the plan of the Pijpenkabinet, the four centuries of the Gouda pipe industry came in these four showcases. Each cabinet had three shelves, so that every century three facets from the pipe history could be shown: the shapes, stem length, marks, decorations or other aspects. Again the job was done by the Pijpenkabinet, not only the idea development but also the manpower.

The accompanying texts were short but clear. The exhibited objects served as representations for the different movements in the history of the Gouda pipe industry. Because the shelves had chamfered triangles on the end faces of the display cases, an object from pipe history of competing centres was shown and explained there. In short, a well thought-out story based on representative objects with a close relationship between objects and text.

The opening of the renovated room took place on February 19, 1988 and was performed personally by the now-aged senior director Bert Helbers. The break with the past was clear and Helbers almost got a cardiac arrest from the tight business design, because it was fifty years earlier that he stood for the homely atmosphere of De Moriaan. Nevertheless, the transformation was an important step in the process of becoming from an urban antiquity room to an educational museum for the Gouda ceramics industry.

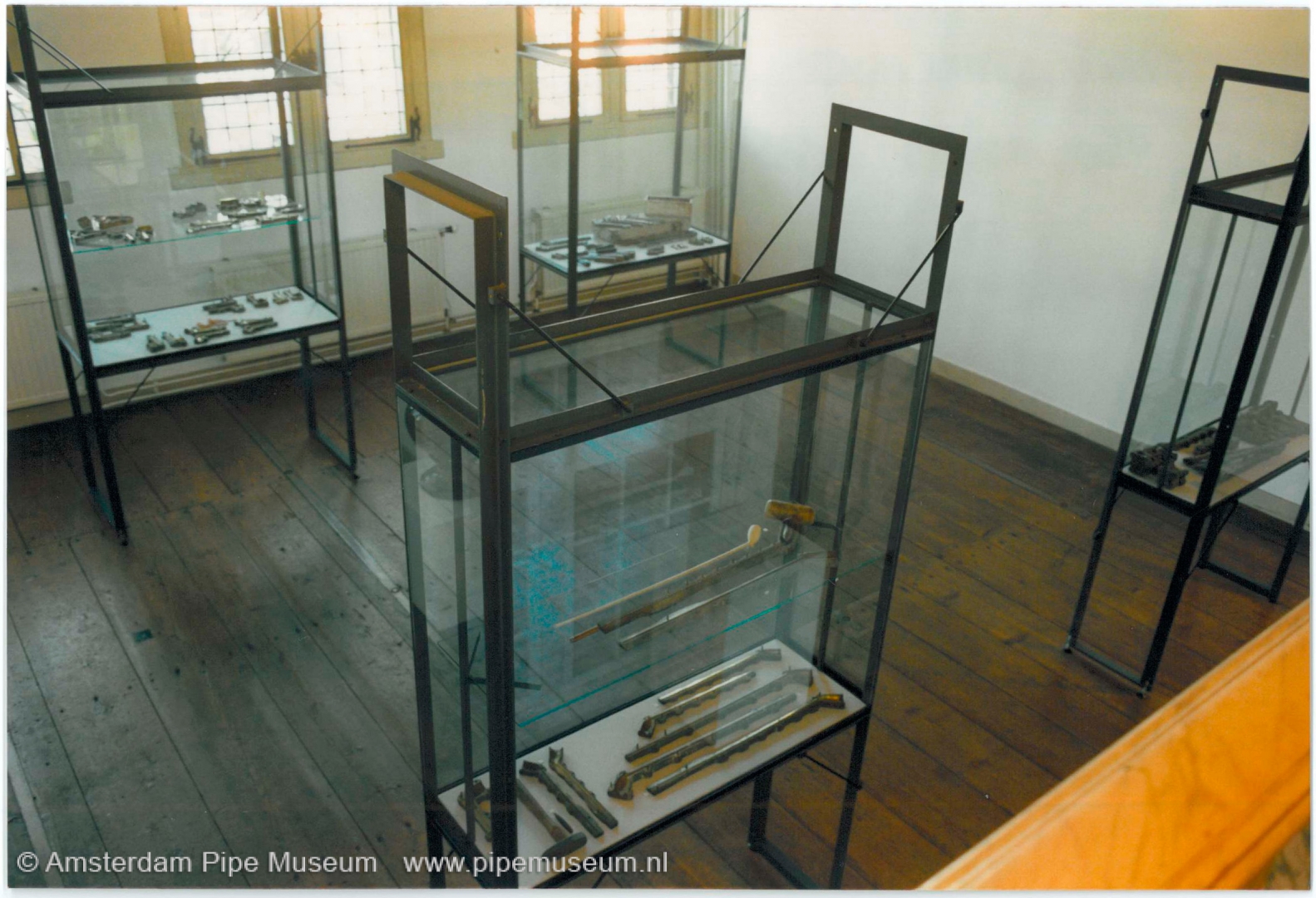

Now that the ties with the Pijpenkabinet had also been placed under the new director, it was time to see to what extent the two subsets could reinforce each other. In October 1989, for example, a double exhibition of pipe moulds from the former Koninklijke Goedewaagen property in both Leiden and Gouda (note 28). The reason was the transfer of this material from Goedewaagen to the Leiden museum, after Josine de Bruyn Kops had refused this collection. In the end it was not a close collaboration: Nicolette did not want any interference in her business and the marriage with the Pijpenkabinet would not last long.

As noted, the redesign took place in 1988, a few years later a new course was set out. Was this an ad hoc policy? Nicolette Sluijter had founded Goudse Catharina Gilde in November 1988 and sponsor money was available to get De Moriaan up. In January 1992 the museum closes for a thorough renovation, but would open again that summer (note 29). Eventually, this was done in August 1993. During this renovation, the building is painted from top to bottom, receives central heating, new electricity and adequate security and all other necessary accessories.

Then it is also time for new showcases, for which a design agency is called in. Josine was so successful with the beautiful switch cases in the Gasthuiskapelzaal. This would be a failure in De Moriaan. There are all-important showcases, too big and too heavy for the small scale of the seventeenth century building. In colossal cabinets that leave a narrow aisle for visitors, the new presentation is set up. De Moriaan gets a new face thanks to the Goudse Catharina Gilde. Provincial cosiness makes way for a design dictated by self-righteous designers who propagate the postmodern design, so completely unsuited for the Dutch simplicity of the building.

The concept of the public presentation, however, remains virtually unchanged. The ground floor is intended for the pipes and the tobacco history, on the floors the Gouda pottery is housed, which is no longer dominated by the typical Gouda pottery, but to which serial ceramics from the later period were added. As far as the pipes are concerned, the content was already established in 1988. The museum is attempting to purchase the loans from the Pijpenkabinet, partly in order to break the ties with Leiden. If that purchase fails, Gouda will contact collector Ab Vrij and his collection was taken over to make the presentation in De Moriaan new style possible (note 30). The loans from the Pijpenkabinet go back to Leiden and the collaboration ends.

For the new fitment, collector Hans van der Meulen is asked. Unfortunately, what he does is by no means deserving: the existing concept is literally recreated in the new showcases, now on the basis of the objects from the Vrij collection. In itself good counterfeiting is not a problem, but the refinement of the original concept was not carefully studied and understood so that the result lacked any coherence. The pipes are shown outside their historical context, with nosy texts, almost like art objects. The captions no longer deal with the specificity of Gouda's pipe history. But ... the Gouda pipe is on view again.

On the initiative of the Pijpenkabinet in 1994 Job van Doorne, who founded the Goudse Catharina Gilde with his organization bureau, scrutinized whether the time was right to establish a joint venture between the pipe and tobacco collections in the Netherlands with the De Moriaan as location. In addition the Pijpenkabinet Foundation, would contribute with its collection and the know-how, while Niemeyer was interested in transferring their museum from Groningen to Gouda as well. With that plan, the ceramics would end up in the attics of the Catharina Gasthuis and De Moriaan would become a pipe and tobacco museum. Director Sluijter is initially in favour of this plan but Niemeyer is finally asking for an unjust financial contribution. When this bounces off Niemeyer, Sluijter does everything possible to counteract the plan for fear of losing control of De Moriaan while the influence from Leiden would become bigger. Despite the positive advice from Gouds Catharina Gilde, the plan does not take place; Sluijter is held accountable by both the Council and the Gouda Rotary through this move. Shortly afterwards the Pijpenkabinet moves to Amsterdam and establishes the national pipe museum there.

In the nineties the interest in the pipes and tobacco decreased, under the influence of the anti-smoking lobby, while the interest in the general craft industry increased. It is time to exhibit more ceramics and more space in De Moriaan is destined for this. With this in mind, the pipes presentation in 1998 is moved to the peat loft in order to have the main floor available for temporary exhibitions. With one display case less, the pipe presentation fits exactly in the new space. In this low room, the design showcases look even more colossal, while the historic line of the exhibited disappears completely by making the pipes fit is less space. Again it is Dirk van der Want who speaks openly about this decline.

In the mid-1990s, curator Gerrit Willems embraces Van der Meulen once again for a publication on the Gouda marks. Van der Meulen believes to have found the missing guild books on pipe makers marks and wants to publish that. The museum then enters into a new marriage with the collectors' circle the Pijpelogische Kring Nederland. This results in a number of initiatives such as an exhibition by the Leiden collector Ruud Stam. From June to September 1999, under the title Pipe and Politics, he presents pipes with a political theme, copied from the successful tour of the commemorative House of Orange pipes from 1992-1996 by the Pijpenkabinet, brought in seven museums (note 31). Perhaps not the right choice, because Stam build up his collection with seconds from the Pijpenkabinet. However, the visitors will not have noticed. The accompanying brochure deals with the theme without much cohesion and without synthesis.

With the departure of Gerrit Willems to Dordrecht, his place is occupied by curator Ewoud Mijnlieff, who takes office in 2001. He continues the line deployed by Willems, a predecessor as inspiration is a safe basis. One of his first pipe acts is the exhibition Gouda had er tabak van in 2003, arranged by members of the Pijpelogische Kring. Then the atmosphere around smoking became even grimmer and activities in this area scored even less. The Gouda pipe received no renewed attention, the step-like presentation on the turf loft was further dusted.

New course

When Ranti Tjan took office as new director in August 2004, a number of old situations broke rigorously (note 32). After two women-directors, it was again time for new ideas with a new positioning of the Gouda museums, partly because of the changed trends in the Dutch museum world. The simplified name of museumgoudA makes its appearance, the capital letter at the end of the word gets used up quickly, although the idea lags far behind the naming of, for example, the Kunsthal. This new name must become illustrative for the changes in the Gouda museums.

In public presentations Tjan unfolds a strong policy for the museum. Collecting does not have to be done anymore, there is sufficient material among collectors that can be used as loan for exhibitions if necessary. The permanent presentation should be about three themes: religion, emancipation and social renewal. This can be expressed in the typical Gouda subjects such as the Reformation, the Gouda pottery industry and the collection of women's art initiated by Josine de Bruyn Kops. The clay pipes could also be given a place here as an example of a craft that developed into an industrial company and eventually came to an art production via the Gouda pottery. For the time being, there is little to discover in the museum itself of this theory. The Gouda ceramics, for example, are shown with a selection as individual art objects. It seems that the curators have not yet mastered the philosophy of their director.

In the meantime, the old storage or archival function of the museum is under discussion, and the upcoming collection is the result. Tjan had already gained experience in his previous position at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht. One of his first shocking actions is an exhibition of objects that, in his opinion, are on the nomination to be removed from the collection. This exhibition takes place in the summer of 2005. MuseumgoudA thus attracts national media attention but also disgust with the population of Gouda. Also the pipe collection can be cleaned up, everything that is not originating of Gouda can in principle be dissolved. Problem however is that nobody in the museum staff can distinguish Gouda and non Gouda pipes. The compromise therefore becomes to keep the Dutch clay pipe. However, the practical execution of the divestment includes a lot of administrative tasks. After a first selection of objects, the staff gives priority to other activities.

A topical theme in the 2000s is the coordination and collaboration among museums. The best example for this is the Dutch ethnological museums. Through mutual consultation and with a joint purchase budget, the collections are expanded and exchanged without competing. In fact, there is one large collection, although the sub-areas are housed in different museums and they are under different managements. The Pijpenkabinet from Amsterdam took the initiative to bring the museums for pipes and tobacco closer together, after this attempt was stranded in 1994. As first action, it published a brochure in 2006 to jointly promote these sub-collections. Because of the individualism of the partners, it was not possible to even discuss any follow-up contact to cooperation, let alone get off the ground, museumgoudA was no exception.

In all the changes of recent years, the change from De Moriaan to National Pharmaceutical Museum is the largest. The ancient pipe and pottery museum will receive a new museum destination; a new construction is putting an end to the endless tug-of-war of the politicians to close the museum and to end the exploitation costs. The pharmacy sector is going to rent De Moriaan building for a pharmaceutical museum to be established, of which the Dutch pharmacists will pay for the exploitation. The building becomes an exponent of this industry and with that the ceramics and pipes become homeless. They are moved to the city museum on the other side of the canal.

In order to make up for the population of Gouda the closure of their accessible museum, it is of course necessary to make a worthy presentation of both fields of collection in the Catharina Gasthuis. After the Gouda pottery the pipe exhibition is scheduled for 2007. Already in 2006 some orientation discussions took place between the Pijpenkabinet Foundation and director Ranti Tjan, from which the wish emerged to obtain a one-off advice from the Pijpenkabinet for a historically responsible pipe presentation. Curator Mijnlieff apparently thought differently about this. In mid-2007, the history of the Gouda pipe was opened in the former Arzenius rooms, completely according to their own insight.

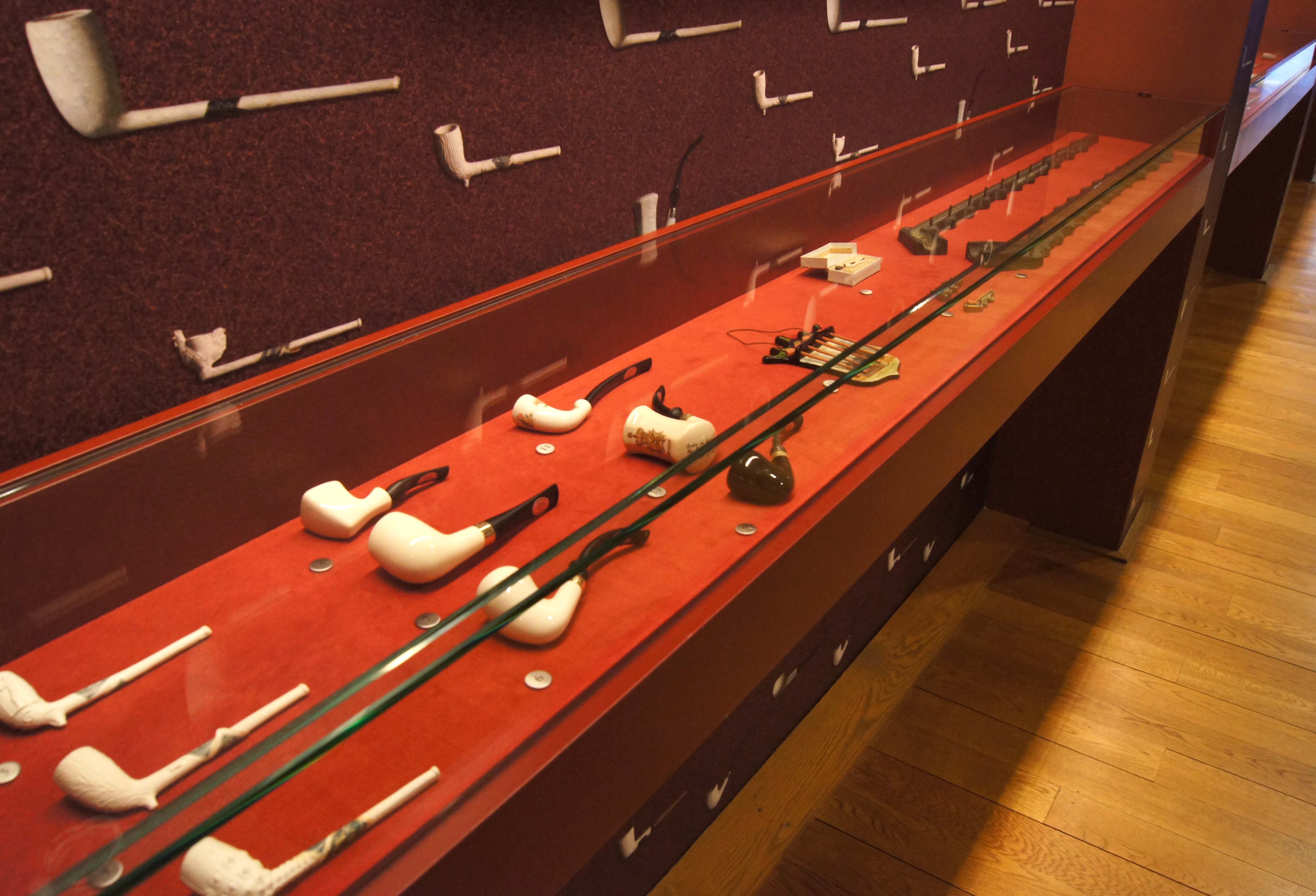

Further consideration of the new permanent presentation, however, gives a little impressive picture, because the design seems to have been made from design and content rather than from design. In that respect, the error of the redesign of De Moriaan is repeated, again under the auspices of Gouds Catharina Gilde. The long narrow space in the ridge of the former Catharina Gasthuis was thoroughly renovated and transformed into a beautiful museum room with shallow niches on both sides with long, narrow, horizontal showcases. The dark space was enormously brightened by applying a wall print in these niches with a warm burgundy colour on which clay pipes can be seen with a certain rhythm. In short, a successful atmosphere for a solid historical story.

Unfortunately, the latter did not come about. Against every museum rule the running direction was made contrarian; even more confusing is the lack of any theme. The criteria of selection of the objects remain completely unclear. The twelve showcases, six on each side, seem to have been arranged without a theme. With the same rhythm as on the wall prints, all kinds of excavated clay pipes are shown whose relationship to the history of the Gouda pipe industry is completely unclear. In short, the major lines of Gouda's pipe history are by no means made clear.

On the two end sides of the hall the showcases with pipes are interspersed with some larger objects. One side shows the unique guild board and the accompanying chest of the pipe makers' guild. As some sort of lost object we also find here an ugly reconstructed pipe saggar from Alphen aan den Rijn, the Gouda counterpart was apparently untraceable. The other side shows two smoking chairs from the time the cigar was in, a pipe stand - not the best in the collection - and the famous goblet with the pipe mark from Bastiaan Overwesel. The visitor must distil a story line from these separate objects. In short, there is no effect, without clear content, the public will not be wiser.

A hall paper seems to offer some hold for the excavated clay pipes in the showcases. Who the compiler is, is unclear, but it is obvious that the pamphlet is printed before the spelling finder and a proof reader has seen it. Language errors are all over. In a somewhat long-winded style the Gouda pipe is discussed, here and there with an abundance of details, evidently intended to showcase historical knowledge, but simply taken from the obvious manuals. The big line remains completely out of sight: nothing is mentioned about the size and expansion of the industry. For the Gouda pipe again a missed opportunity and that in the city that is better known in the world for its pipes than for any other article. The interest of the museum staff and contempt for the subject should be the underlying idea. For the visitor, at least disappointing and little instructive.

It is clear in any case that seven decades after the opening of De Moriaan as a pipe museum there is still no unique presentation of the Gouda clay pipe in Gouda. At the time, Helbers was behind the private collections in our country. Later that position was taken by the Pijpenkabinet. Then Gouda let go of the opportunity to draw a national museum, while at the same time she did not want to use the expertise of the colleagues. It seems that the new presentation in the ridge of museum gold is made to disappear quickly. Too trendy and fashion sensitive in design and minimal content this presentation after a few years and low valuation can be removed silently and thus sweeps Gouda its pipes history under the mat. Everything points to the fact that museumgoudA advocates this policy, a method that curators in Dutch museums are more often accused of. Time will learn what direction this change really has taken.

© Don Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Amsterdam – the Netherlands, 2008.

Illustrations

- Newspaper clipping on the reopening of the pipe exhibition in museumgoudA, Summer 2007.

- The impressive facade of De Moriaan building along Westhaven in Gouda, Holland.

- Interior of the historic tobacco shop.

- Work space of the Gouda pipe maker in the notch attic.

- Letter from D.A. Goedewaagen on a pipe donated to the museum.

- Visit of queen Juliana to museum De Moriaan.

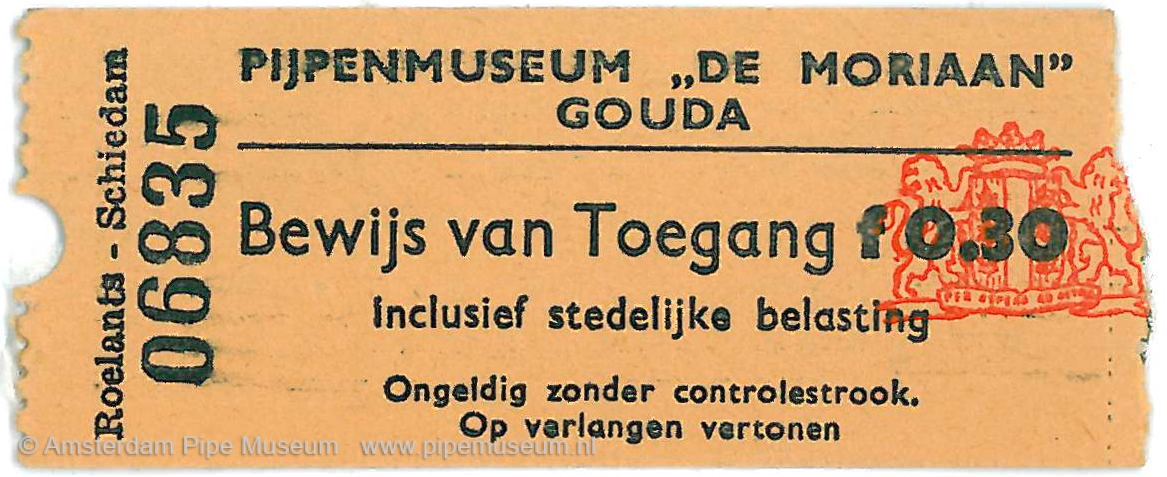

- Admission tickets to museum De Moriaan.

- Poster of the exhibition Gouda / was eens een / pijpenstad, Summer 1983. Design by Tjaard Jager.

- View in the exhibiton Gouda / was eens een / pijpenstad, Summer 1983.

- One of the numerous newspaper clippings on the topic to close or not to close the museum De Moriaan.

- The presentation in De Moriaan showing the Gouda pipe history in a modern way, 1988.

- Double exhibition dedicated to pipe making tools.

- The new pipe presentation in the attics of the Catharina Gasthuis.

All illustrations from Pijpenkabinet documentation, Amsterdam.

Notes

- Krant van Gouda, 13-07-2007.

- Dr. Jan Schouten, Gouda van sluis tot sluis, De geschiedenis van Gouda in de negentiende eeuw, Den Haag, 1977, p 138.

- D.H. Duco, Bronnen tot de geschiedenis van de pijpennijverheid in Gouda, Amsterdam, 1976, G1872-06-03.

- G1911.

- G1876-07-26.

- G1875-02-08.

- G1891-07-06.

- G1911.

- G1875-1877, G1877-02-12, G1877-03-06, G1890 c..

- G1874-1943.

- G1897-04-15, G1897-08-07.

- G1954-05-08.

- G1931-06-23.

- G1934-06.

- G1938-03-08.

- G1939-02-08.

- G1940-08-10.

- The material possibly originate from Ruhla, Thüringen and has never been used for production in Gouda.

- G1941-06-11.

- G1944-06.

- G1934-12-21.

- G1944-1956.

- De Nederkandse Musea, ’s-Gravenhage, 1954, p 119.

- G1957-1976.

- G1983-07-08, Goudsche Courant, 17-08-1983, Rien Wilpert stands for Dr. Jan Schouten.

- Goudsche Courant, 06-03-1984. Rijn en Gouwe, 22-10-1987.

- G1988-02-19.

- Holland Silhouet, 18-10-1989. Leidse Post, 18-10-1989.

- Algemeen Dagblad, 24-01-1992.

- Goudsche Courant, 19-09-1992.

- This exhibition tour started as "Ik rook Oranje" (I smoke Orange) in Palace The Loo and continued as "Vorstelijke pijpen" (Royal pipes) in four Dutch and two foreign museums, was not on view in Gouda to demonstrate the pour interest for the Gouda pipes in the Gouda museums.

- Goudsche Courant, 06-07-2004.