A special press mould for a pipe dedicated to the House of Orange

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

Een bijzondere persvorm voor een Oranjepijp

Année de publication:

1993

Éditeur:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description :

Depiction and discussion of a brass press mold with the portraits of Stadtholder William V and his consort Princess Willemijntje of Prussia and the history behind this object.

Most of the press moulds used in the pipe-making industry were intended for the conventional pipe shapes that were part of the regular assortment. Such press moulds did not last long: the abrasive clay wears out the brass material. After they were taken into use, they became worn within a few years, often being renewed without any change or replaced by a more fashionable shape. However, when it comes to producing press moulds with a engraved decoration dedicated to a special occasion, the number of clay pipes produced is much smaller. Some engraved pipe moulds with a somewhat general decoration could stay in use significantly longer, the pipe being an addition to the assortment. An interesting example of this is a press mould in the Pijpenkabinet collection, which has served almost a century and a half for production, obviously at intervals. This press mould was previously the subject of publication, but in this article its history is completed.[1]

The original decorated pipe

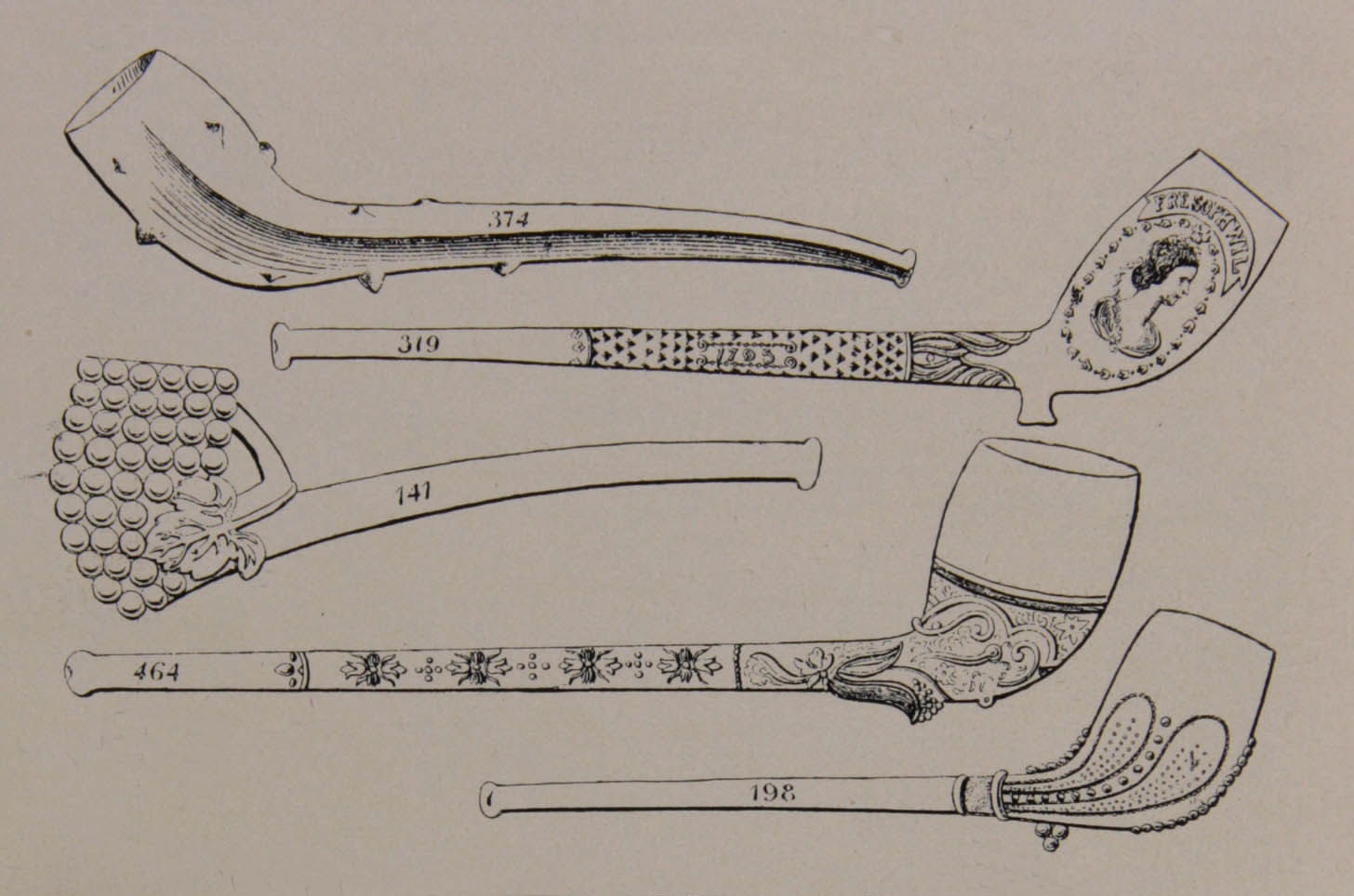

The press mould in question is dedicated to the Dutch royal family, the House of Orange and was engraved in 1767 or shortly afterwards on the occasion of a stadholder's marriage (Fig. 1). The clay pipe from this press mould shows on the bowl the profile portraits of Prince William V and his consort Princess Frederica Sophia Wilhelmina of Prussia. Both portraits are framed by a kind of oval branches with fantasy leaves that most closely resemble the acanthus. Text ribbons with cut ends swirl along the bowl opening. On the left we read “WILLEM V. P.V.O”, the abbreviation for Prince Van Orange and on the right her abbreviated name “FRE. SOPH. WIL”.

The production date of this press mould is uncertain. The marriage of Prince William V and Princess Wilhelmina of Prussia took place in 1767, that is the oldest possible date of the engraving. However, the question is whether this pipe was made on that occasion or later as a commemorative piece. A few years later seems more likely, which is supported by the decoration of the stem that I will come back to later. A date of the engraving between 1770 and 1775 is therefore the most plausible. The first production period of this pipe runs until the year 1795, the moment of departure of the Stadtholder to England to stay out of reach of the Napoleonic troupes.

The bowl shape of the pipe is not oval as is the case with most embossed pipes, but more cylindrical and has a round bottom without heel. Such pipe models are called casjotte or cajotte pipes. The name is derived from the long narrow pocket in the trousers of the French farmer, who let the pipe slip into that pocket to carry it with him. Since the French were major customers of this pipe shape, the French name was also taken over in Holland. The original Gouda name for this decorated version is a gewerkte casjotte, the first word means literally worked indicating engravings in relief. The tobacco pipe is therefore not of the usual type but can be seen as special shape, in this case basic model 5. The pipe has a relatively short stem of about 21 centimetres, shorter than usual in Gouda.

Not only the bowl is decorated, also the stem of this pipe is adorned with an embossed fish with opened mouth near the pipe bowl and a scaly, rather unshaped body. At the end the decoration is closed with a simple band with a few leaves. The rest of the stem is undecorated up to the mouthpiece. In the eighteenth century these pipes were called snoeckebek, to be translated as mouth of a pike.[2] Originally, the fish motive is mainly known from clay pipes made in the German Westerwald where this decoration is conceived. In the province of Holland this decoration was imitated by pipe makers in Schoonhoven and Gorinchem. In Gouda the fish was hardly popular.[3] The reason is that the design was applied to the better types of short pipes; Gouda had its focus on the long clay pipes and produced the short pipes only to a very limited extent. Nevertheless, the pipe mould of this article is of Gouda origin.

At the time of introduction, this clay pipe had a clear propaganda value. Although Stadtholder William V was not known as a capable ruler, the House of Oranges still had the support of a large part of the middle and lower class Dutch population. It is therefore understandable that the choice for this decoration did not fall on a stately long pipe, but rather on a somewhat shorter, more convenient model for a broad target group. However, since poverty prevailed in the Gouda pipe making industry, saving on the costs for a new press mould was welcome. For this reason the choice was made to reuse an old casjotte mould, a product between fine and coarse and therefore suitable for a variety of customers.

The choice for this shape was not a very logical one. The casjotte pipe was simply not a prevalent nor favourite shape in our country and therefore not in line with any common sense. Perhaps the maker opted for a sale of this product to Prussia, Princess Wilhelmina being the daughter of the Prussian king. Both in terms of the shape of the bowl and the stem decoration, this wish would have matched well with the prevailing taste. However, there is no evidence of such a sales channel in the form of archival documents, accounts or archaeological finds.

On the bottom of the bowl the pipe is provided with a stamped maker's mark, the number 666. Thanks to this brand stamp, we know the maker named Gijsbert van der Spelt from Gouda. Van der Spelt became master pipe maker in the Gouda guild in 1745, but left for Aarlanderveen five year later, in 1750.[4] He worked there for half a year in a local pipe factory, but he quickly returned to pick up his old profession in Gouda. His marriage must not have been very happy, he lived separated from his wife, which was certainly not common habit at that time. It was not until she had died that he remarried. From that moment on his career took a favourable turn and he worked himself into a more prestigious independent pipe maker. His second marriage in 1769 almost coincided with the engraving of this press mould.

Returning from Aarlanderveen Van der Spelt was probably seen as a kind of deserter from the Gouda pipe makers' guild. He had worked for the competitors of the Gouda industry in the area around Alphen, no more than 20 kilometres away. There is no re-entry of him as a master pipe maker in the Gouda guild ; he was probably not allowed any more to become a guild member again. Van der Spelt remained a somewhat shadowy person because, due to the lack of his name in the guild registers, it seems that he practiced his profession unofficially. Likewise he no longer appears as a paying member in the guild members book and possibly he was so ignored by his colleagues that nobody cared about him. Yet he apparently was not impeded from practicing his profession.

In short, his career remains vague and nothing is known about the end of it. When his second wife Marrigje Marté was buried in 1795, Van der Spelt himself appears to have died already. From the fact that she dies as a poor person, we have to conclude that the pipe making did not really bring the couple good fortune.

It is unknown whether the pipe makers’ mark 666 is the only mark stamped on this decorated casjotte pipe. It is possible that Van der Spelt possessed the press mould for a short time only and other makers have worked with it as well. It is even feasible that he had the press mould on loan to make an order and the mould was later used by other makers as well. The right to ownership of the 666 mark transfers in any case to Hendrik Schoon in 1783, although it is most unlikely that this press mould also changed hands on that occasion.

For sure the marketability of this decorated pipe must have been excellent in the 1770s. The political situation around Stadtholder William V was still relatively stable. There were enough Orange adhered smokers for such a pipe. In the 1780s the sales decreased, with the year 1784 as the lowest point of interest. In that period, most Gouda pipe makers become Patriots. For the Orangists however, the victory comes in 1787 when on so-called Dolle Maandag changes came. Until 1795 there must have been a wider market for this embossed pipe to finish definitive with the French domination.

The press mould

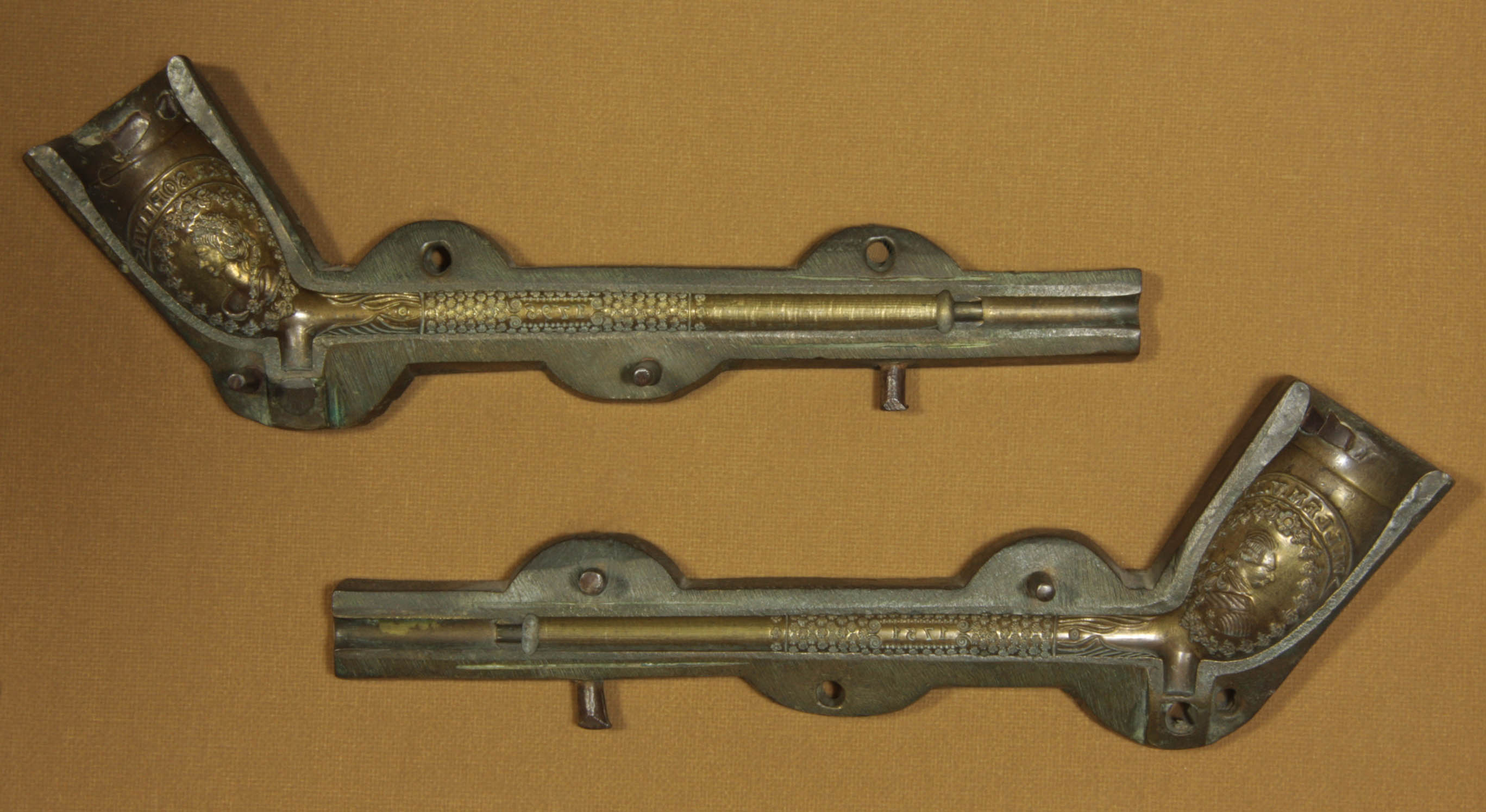

The brass mould for this clay pipe is of the usual Gouda type in two parts, that are identical but mirror-like mould halves (Fig. 2). Along the top and bottom of the pipe stem the mould is provided with cams holding the closing connection in the form of slightly conical iron pins and corresponding holes. These locking pins fall unperturbed in the opposite holes. The most important part of the mould makers profession was, of course, the perfect closing of the press mould which was done with the aid of a lead model, a solid pipe.[5]

Presumably four cams with pinhole connections sat on both sides along the stem of the press mould , ensuring smooth closing. It was customary to place the locking pins in such a way that they had a minimal chance of coming into contact with the newly pressed, yet wet pipe when opening the mould. Before removing the pipe, the right half was pushed forward by a right-handed man, after which the newly pressed pipe was removed from the left half of the mould. The pins of the halves were thus always kept as far as possible from the still wet pipe, so that there was a minimal risk of damage.

It is almost certain that the engraving in this press mould was not applied in a pristine (Fig. 3). It was customary that a pipe maker brought a decorated pipe on the market on a special occasion, using an older press mould. This had an economic reason and had to do with the expected sale of the decorated pipe. With a time-bound decoration, the value of the pipe is of limited duration, so the production is limited and it was economically more sound to sacrifice a used press mould instead of a new one. Each manufacturer can estimate approximately how many pipes will be sold. Once the mould was engraved, it was irrevocable and no other decoration could be applied, although it is possible to make adjustments within certain limits.

In the so-called crown of the press mould, the space above the pipe bowl, two steering pins are set on both sides (Fig. 4). These loose-laid iron pins serve to guide the stopper in the pipe bowl and keep it as much as possible centred. These steering pins allow the clay surplus to exit the mould between the iron pins. Moreover, the iron is significantly more wear-resistant than the brass crown of the press mould itself so that the punched-in pins protect the mould from wear.

This press mould has been in intensive use, which can be seen not only in worn steering pins but also because the object exhibits numerous other wear marks. For example, the bowl has been worn down on the top. Especially directly under the rim of the bowl, where the relief has the strongest wear by the abrasion of the clay the decoration is rather weakened. That is why it was necessary to re-engrave the text ribbon again which is done just a little too strong by means of a burin. The locking pin under the bowl became so worn that a new repositioned one was made to get a better bond (Fig. 5). To ensure proper closing of the stem, the stem edge has also been raised, proved by longitudinal grooves.

The strong wear of the press mould is also reflected in the decrease in weight.[6] The mould now weighs almost one kilogram, but originally this will have been about one kilo and four ounces. During use, the mould edges wear due to the abrasive action of the clay. At regular intervals it is necessary to bring the press mould back in the right condition, in Dutch named ophalen. At that moment the iron locking pins are removed from the mould, after which the two mould halves are sharpened on a large sharpening stone. Due to the frequent sharpening of the mould, the bowl and the stem of the pipe gradually become oval. At some point it is necessary to deepen the bowl and stem, for which special files are in use. With embossed pipes, the engraving has to be updated again. In the end, the pipe will gradually being cut through the brass. Since in our case the original engraving is still in reasonably good condition, this indicates that the bowl engraving has hardly been sharpened after being engraved. On this basis it can be concluded that this press mould had previously been used without decoration.

The modernization of the press mould

We don’t know the exact moment, but undoubtedly due to change in fashion this engraved press mould was put out of use at a certain moment, but not discarded. Evidently the portraits of Prince and Princess were still valued, at least regarded as more important than the value of the brass if melted down. The mould even survived French domination, a period in which depictions of the House of Orange were forbidden.[7] Somewhere in the nineteenth century, this outdated press mould was rediscovered . In order to produce a new edition of the pipe, it was seen necessary to give the product a fresh appearance, which means adjusting the mould. After many decades, the casjotte shape was out of fashion so the challenge was to adjust the shape as much as possible . The actual bowl shape remained unchanged because apparently the original engraving was respected. By adding a heel, however, the pipe got a completely different look. Because of the heel, which clearly distinguishes bowl and stem part, the bowl shape tends more towards the curved pipe bowls although the typical casjotte shape remains visible.

At the same time the stem of the pipe was drastically shortened, even reduced to 11.5 centimetres in length. There are two reasons for shortening the stem. The weary press mould closed particularly bad at the stem end, which often caused a frayed mouthpiece . By shortening the stem this problem could be solved. In addition, the short-stemmed pipe was more in fashion at that time. Completely unusual for this pipe shape, but again according to the period, the stem was provided with a knob mouthpiece, while the thickness of the stem was increased by a fraction. By all these changes we can conclude that the refashioning of the mould would have been done somewhere in the 1850s.

It was also necessary to adjust the dated fish decoration that gave the pipe an unsympathetic appearance. By concealing the head of the animal with stylized sequins and applying years on both sides of the stem, the pike seemed to disappear and the stem became ornamental (Fig. 6). The original fish has now become a repetitive ornament with a rectangular shield showing the dates 1751 on the left and 1795 on the right. Those two dates indicate the formal of Stadtholder William V and his departure to England. This altered the once topical bowl decoration into a commemorative item.

When changing the stem decoration from figurative to ornamental, inevitably a style difference was caused between the bowl and the stem decoration. While the smooth lines of the bowl had lost its sharpness, the newly punched stem decoration was extraordinary clear-cut. The pipe also got a hybrid character due to the difference in nature between the artistic, fluent bowl decoration and the mechanical stem decoration. The original decoration, even though worn now, was extremely elegant , while the added punched decoration was sharp and rigid.

Shortening the stem of the clay pipe by cutting of half of the mould, caused a technical problem. The press mould was no longer sitting parallel in the screw during pressing, since the supporting last cams was now missing. To solve this problem, the mould maker inserted two iron support pins underneath the mould (Fig. 7). If the press mould would not lie horizontally in the vice, the handle of the iron wire would get stuck, inhibiting the piercing of the connection to the pipe bowl. Furthermore, a brass cylinder was placed directly behind the knob mouthpiece for narrowing (Fig. 7). This narrowing had to prevent the clay from being pressed out of the mould on that side when the stopper pressed the bowl opening with considerable force.

Presumably the change of this press mould took place around the year 1855 in order of Hendrik van der Pool, who established himself as an independent pipe maker in 1839 in Gouda. Van der Pool is not a member of one of the traditional pipe making families, but he was a newcomer, even though his father died young as a pipe maker's assistant. Despite the economically unfavourable times, he succeeded in securing a worthy place among the existing companies. Already after ten years of independence, he employs nine workmen, a few years later his business has even grown to twelve adults and eight children.[8]

His assortment contains the customary so called maatpijpen, traditional long Gouda pipes, but he also had a miscellaneous selection of odd/unusual short pipes. With this, Van der Pool is responding accurately to the new fashion that has arisen since 1840 when the consumer developed a growing interest in short stemmed pipes with a new, more alternative bowl line. This development is still in an experimental phase and in many cases new pipes are shaped by the conversion of old press moulds into new creations. Starting point is an unexpectedly looking product that cannot always pass the test of aesthetics.

During his career, we see Van der Pool looking for suitable tools at virtually every public auction in Gouda. In the course of the years, he will have expanded his assortment with an incoherent variety of unconventional pipe shapes. Unfortunately, little more is known about this than some pipes that have come to us as archaeological finds. By chance, an excavated pipe bowl is known from his company, produced in the press mould discussed here (Fig. 8). On the heel this pipe bowl shows his makers’ mark WL crowned. The experimental character of Van der Pool's product assortment is also evident from the fact that this find is black-baked, so a special finish.

Due to the size of his factory and the unexpected assortment, Van der Pool positions himself as a special pipe manufacturer, no doubt someone with merit. Perhaps the fact that he had not grown up in the Gouda pipe-making tradition was the reason why he concentrated on a new and a-typical range of pipes, more than other manufacturers. His progressive way of working is also evident by the mare fact that he participates in the General National Exhibition in Haarlem in 1861. The later years of his career continue quietly. In 1873 he became ill and decided to sell his business, after which the company was dissolved in 1874. A year later he dies in the Catharina Gasthuis, the hospital in Gouda.

It is unknown who took over his production material. Often, there were several buyers in such liquidations because almost none of the companies had the ability to invest seriously . The auctioning of tools among colleagues was a much followed way of selling out. Presumably, after public sale countless press moulds will have begun to roam from maker to maker till they finally end up in the melting pot. Different from many other failing companies at that time, no auction information on the closure of Van der Pool’s factory was recovered. However, there are two companies that qualify as successive owners of the Willem V press mould: Jan de Gidts and Gerardus Johannes Wagenaar. It is waiting for a hallmarked pipe find to prove the missing link in the chain of ownership, if we assume that the press mould has been taken back into production. In or shortly before 1895, the press form finds a new owner again.

Reuse with a new maker

Around 1894, the press mould changed ownership. Buyers are Pieter and Aart Goedewaagen who together run P. Goedewaagen & Sons.[9] For Gouda standards this company was exceptionally wealthy in those days. As far as possible, this firm bought press moulds and other tools for reuse in their own company from small independent workshops that liquidated. The purchase by Goedewaagen often aim to obtain a monopoly position, with the underlying goal not to give other makers the chance to expand their assortment. Incidentally, several competitors were also active in this field, such as Jan Prince & Cie, who succeeded as well in building up a considerable collection of press moulds.

At the Goedewaagen firm, the production with this press mould was continued without any change in design. The pipes are now stamped with both the marks IWI and ES with a crown (Fig. 9).[10] In both cases, the modern design of the mark stamp that Goedewaagen had adopted around 1890 is used. There is no deeper reason to use of two marks, they seem to be randomly alternated. Production continues until the year 1910.

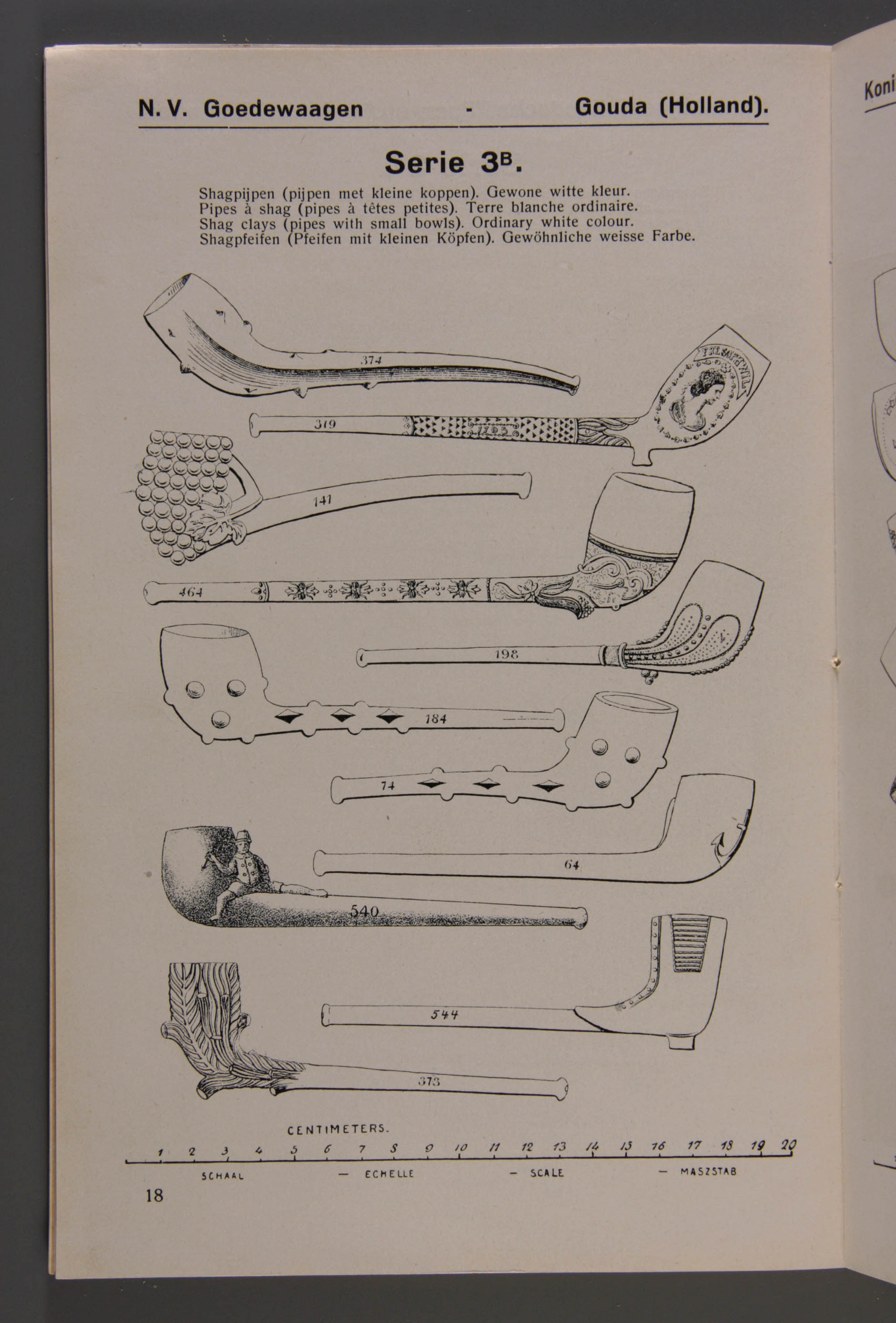

As early as 1880, Goedewaagen had a decent standardization of production. For example, a number list off all pipe shapes was introduced. For the customer the shape number functioned as the order number of the clay pipe, but it was also used in the factory to carry out the production and stock administration. This number was hammered on the outside of the press mould, normally on the front edge of the bowl part . In the workshop the production is divided into series, pipes from the same series are characterized by an equal degree of labour needed. The degree of manufacturability determines the wages that are paid per gross.

From 1890, the Goedewaagen firm publishes catalogues to show their assortment. In order to create a structured pricing, the pipes are shown per series. As said before, series group pipes with similar look and the same price. The Goedewaagen company illustrates the pipe discussed here under number 319 and gives the description Willem V and Willemijntje shag.[11] The name shag refers to the bowl size. Due to the increase in tobacco varieties and flavours, pipes with smaller bowls are renamed shag pipes. In that period the small bowl was common for smoking the so-called fine cut tobacco.

There was no question of a large production of this model at Goedewaagen. This small tobacco pipe was not a product to be sold per gross because the old-fashioned eighteenth-century look had little sympathy with the smoker around 1900. That is why this model only served as a supplement to the range, in particular to make the factory catalogue more impressive. It is not impossible that specimens of this pipe were added to a gross of miscellaneous pipe shapes. In the meantime, the embossment on the bowl was no longer sharp, especially on the top of the pipe bowl, it showed a lot of wear and tear.

Before the First World War, production was discontinued for good. Although, some of these pipe bowls have been found along the Jaagpad in Gouda at the former factory building, that was built in 1908 and taken into use somewhat later.[12] It could be that this concerns breakage of old stock taken from the earlier factory address on the Raam and not production waste. This is most probable since the oxidation in the press mould suggests that no production of this model took place in the twentieth century.

To emphasize the extensive assortment of the factory, this pipe model will remain in the catalogue. Even with the new edition of the catalogue in 1912, this shag pipe is shown again (Fig. 10).[13] That this model 139 still appears in the 1924 reprint is understandable, because for this catalogue the printing blocks from 1912 were used unchanged.[14] As far as to verify, however, the pipe itself was no longer supplied, as was the case with countless other pipes in that edition of the catalogue.

It is interesting to know the price of this pipe shape. In 1903, this pipe is mentioned as a specimen in an assorted gross in the price list intended for sale to New York for $ 3.25 per quantity of five gross.[15] Purchasing costs paid by the wholesaler for such a pipe is less than half a cent. The reported price quotation is an indication for quantities with different models, but it is questionable whether this specific model was also supplied. The already reported poor condition of the engraving could be a reason for not releasing this shag pipe any more.

This House of Orange pipe shows up once more in the price list of 1921. Again, this shape is sold along with various other pipes for the price of ƒ 18 per three gross. The retailer is recommended a retail price of six cents each.[16] It is a somewhat misleading price information, because we know that the product has long since out of production and its stock has been exhausted for a long time. The considerable price difference between 1903 and 1921 is also related to the sharp rise in wages, especially in the period around the First World War.

In conclusion

Only a few press moulds have been preserved from the eighteenth century. Moulds were seen as production material and disappeared in the crucible/melting pot as soon as no more use could be expected. The intrinsic value of the brass was more important than an outdated and unused tool. It is therefore remarkable and probably only due to the commemorative engraving, that this pipe mould survived. The decoration is dedicated to a special, time-bound event, in principle intended for a short period of production. Nevertheless, the mould has belonged for almost a century and a half to the assortment of various Gouda pipe factories.

Studying this press mould in conjunction with the pipes produced in this mould, we can reconstruct the history of a tool and the products made therein. The press mould in question initially served for ordinary casjotte pipes. When the mould was worn and apparently no longer useful for production of the finest pipes, it has been given a time-bound engraving. That happened after the wedding of Stadtholder William V and his consort. The maker is known thanks to the stamped mark on an accidental archaeological find; we can not be sure of the production period, nor do we know much about the producer who appears to be an exceptionally shadowy figure, although we know his name: Gijsbert van der Spelt.

After a long period of disuse, the press mould underwent a drastic modernization around 1855 to be been taken into production again. Result is a somewhat hybrid pipe because of the vague bowl decoration in contrast to the sharp-cut decoration on the stem. It is a pipe with a decoration that was only of interest to the discerned consumer with knowledge of its historical background. Whether the pipe smoker at that time was really sensitive to this decoration remains the question. When a transfer of the mould takes place again around 1894, the last manufacturer-owner sees this pipe model as an unimportant addition to his vast assortment. The model did not yield an economic impulse but only served as an assortment supplement.

The fact that this press mould has been preserved for nearly two centuries to this day is certainly special. For the last century it is thanks to the conservative nature of the firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, which has always cherished their archive of press moulds. Undistinguished among many hundreds of other press moulds, this object survived the time, gradually changing from production material to a curiosity item . In 1976 I was allowed to remove this press mould from the factory inventory to add it to the collection of the Pijpenkabinet together with a few other historical press moulds. The director saw its relevance as an historical object to be preserved. There they went for a future no longer as production material but as a museum object. After Royal Goedewaagen bankrupted, the other press moulds followed to our museum. Even there this very pipe mould remains the oldest mould known.

© Don Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Leiden – the Netherlands, 1993.

Illustrations

- Fragment of a clay pipe with beaker shaped bowl, round bottom and straight stem. Bowl on both sides between branches with leaves the profile portraits of Stadtholder William V and his wife princess Frederica Sophia Wilhelmina of Prussia. Stamped makers' mark on the bottom 666. Gouda, Gijsbert van der Spelt, 1770-1780.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.469a

- The press mould of the House of Orange pipe in open position.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 5.716

- The press mould in open position showing the engraved pipe bowls.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 5.716

- The crown part of the press mould with the worn pins to guide the stopper.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 5.716

- One of the pins for closing the pipe mould replaced.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 5.716

- The renewed stem decoration with the dates 1751 and 1795.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 5.716

- The iron pins in the stem end of the mould to keep the instrument horizontal in the vice.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 5.716

- Black backed pipe bowl from the mould discussed here. Gouda, Hendrik van der Pool, 1855-1875.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 9.280

- The shag pipe from its last period of production. Gouda, firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, 1895-1910.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 6.251c

- Page from catalogue 6 illustrating the decorated shag pipe. Gouda, Koninklijke (Royal) Goedewaagen, 1924.

Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.053

Notes

[1] Don Duco, 'Oranje pijpen', Pijpelijntjes, VI-1, 1980, p 6, ill. 11. D.H. Duco, Clay Pipe Manufacturing Processes in Gouda, Holland, A Technical and Historical Review, Oxford 1980, p 163 and 204, photo 1. D.H. Duco, De tabakspijp als Oranjepropaganda, Leiden, 1992, p 48, photo 45. D.H. Duco, Vorstelijke pijpen, Inventarisatie van kleipijpen gewijd aan Nederland en Oranje, Leiden, 1992, p 51, no. 156.

[2] Don Duco, ‘De stadspijpenfabriek te Gouda’, Pijpelijntjes, V-4, 1979, p. 5. The decoration is placed on the stem, sometimes also on the base of the bowl.

[3] Duco, (Oranjepropaganda), 1992, pp 47-49, figs 47-48.

[4] SAHM, Left persons from Gouda. “Gijsbert van der Spelt en Johanna van der Veer, egteluijden met haer dogter Teuntje, oudt 6 jaeren met acte. Aarlanderveen, 21-09-1750. Gerestitueert 18-10-1751”.

[5] Don Duco, ‘Vervaardiging en onderhoud van de persvorm’, Leiden, 1989.

[6] 0,97 kilogram.

[7] Duco, (Oranje), 1992, pp. 53-54

[8] Don Duco, Biografische gegevens van pijpenmakers in Gouda, Amsterdam, 1976 e.v. Hendrik van der Pool.

[9] Cat. 3, p 17, series 3. Also in catalogue 4A, p 17, series 3B and catalogue 6, p 18, series 3B. This dating is quite sure because the pipe lacks in earlier catalogues than number 3.

[10] Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 6.251c white, heel mark ES under crown (modern version); Pk 6.251a white, heel mark ES under crown (modern version) (archaeological find); Pk 6.251b white, heel mark IWI (modern version) (archaeological find).

[11] Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.199 cahier “Nummers van pijpvormen” (Numbers of pipe moulds).

[12] Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 6.251a.

[13] Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.052 catalogue 6, 1912.

[14] Leiden, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 10.053 catalogue 6, 1924 (second edition).

[15] 1903 New York per box of 5 gross $ 3,25.

[16] Don Duco, Modellenbestand Goedewaagen, Amsterdam, 1978, shape 319 (refers to shape 26).