The showroom collection of the Royal Goedewaagen, what is left of it

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

De toonkamercollectie van de Koninklijke Goedewaagen, wat er nog van rest

Année de publication:

2015

Éditeur:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

Description :

Description of the showroom of the Royal Goedewaagen from the year 1890, the functioning of the showroom and its removal, including the destination of the pipes.

It will be every pipe collectors’ dream is to go back in time and step into the showroom of a Gouda pipe factory. Along the walls there is the range of clay pipes of that moment, the shapes that are in fashion. Possibly divided into series, grouped by type and price. Not only a romantic excursion, but above all a very educational experience because the cohesion of the pipes in production reflects the fashion line of the factory, their achievements and specialties but also gives an insight in the consumer behaviour in general at that given time. Unfortunately, it is a dream, the pipe factories in Gouda have ceased a long time ago and their showroom models have been scattered like their regular pipes. A small part ended up in collections, the majority got lost.

The showroom is therefore an important informer about the company and gives a snapshot of the ultimate factory assortment. At the shopkeeper the pipes are just as immaculate as at the factory but they are handed out from a wooden or cardboard box. The coherence of the pipe within its range is than lost, partly because the retailer carries a limited number of shapes. Finally, the clay pipe is a tool that has become detached from the context of its production and will now be part of the consumer's usage habits. Only the showroom collection therefore gives us the complete overview of the assortment.

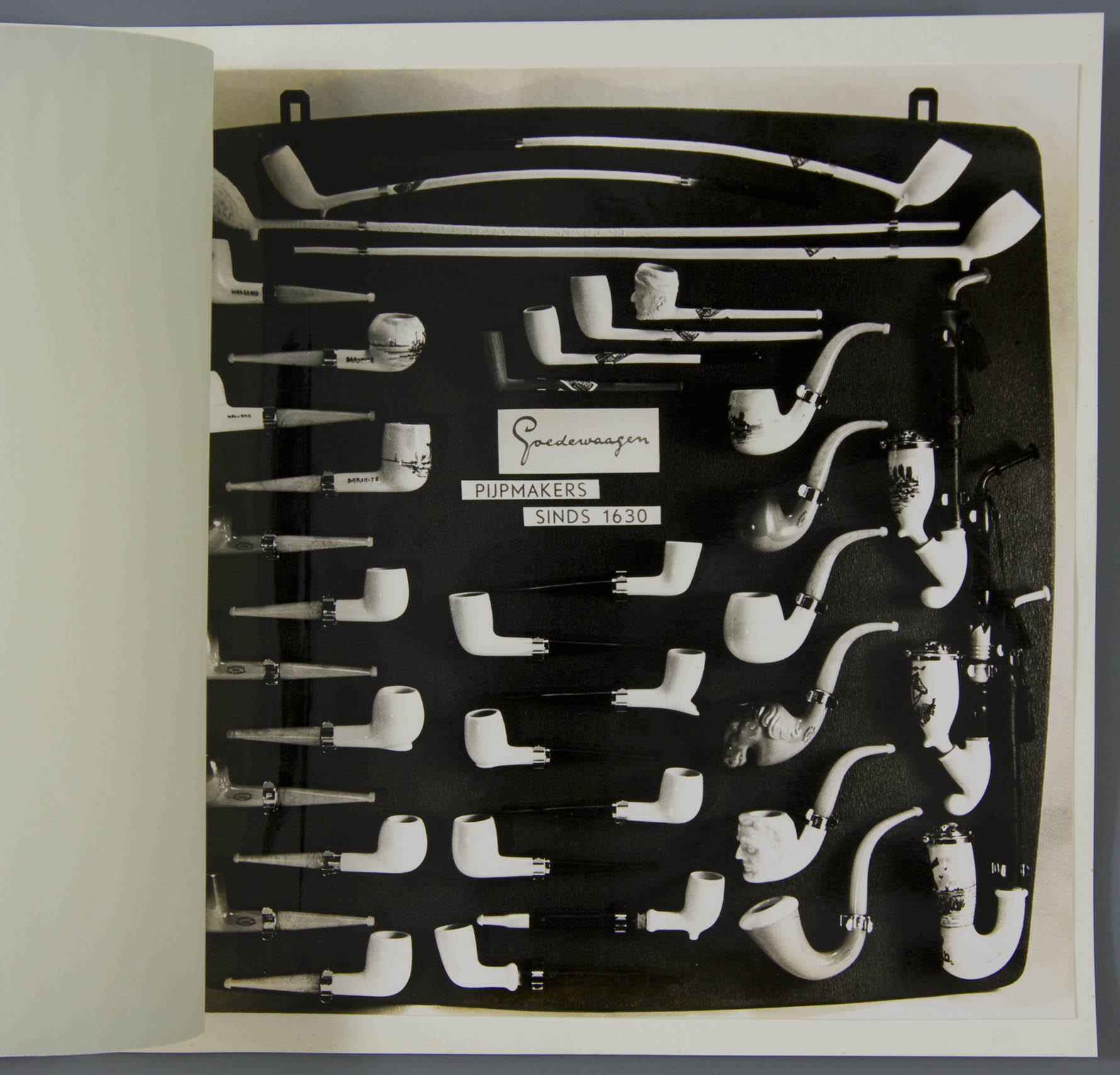

Only from Koninklijke Goedewaagen we have a picture of the showroom also called modellenkamer, shape room. Some photos were kept on which we see the layout of this showroom and can even determine a development through time (Note 1). In addition, some of the pipes from this room have been preserved, albeit exemplary. This article is dedicated to the showroom of Goedewaagen, its functioning and what remains of it.

The nineteenth century forerunner

As mentioned, hardly any information was kept about the showroom of pipe factories, and that certainly applies to the nineteenth century companies. An exception and also the oldest image we have was published by S. Abramsz in the magazine Eigen Haard (Our Fireside) in 1906 (Note 2). It shows two photographs of panels of pipes as found in the former factory of Goedewaagen along the Raam and dating from the last of the nineteenth century. These photos show two large wooden panels on which each clay pipe is stitched on a dark, presumably fabric background.

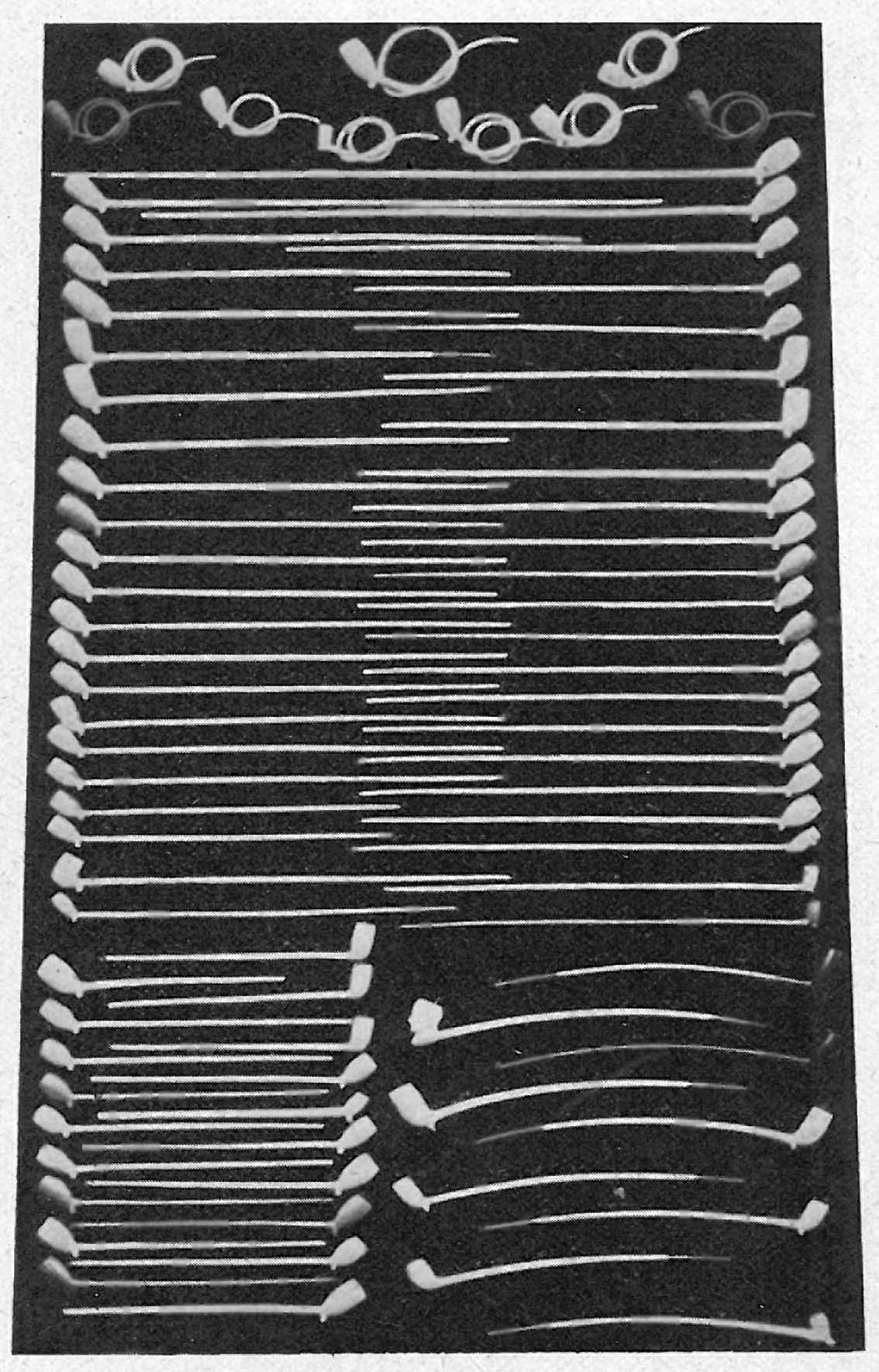

The panel for the longest types of pipes is over one meter wide by one and a half meters high and contains exactly eighty different pipes (Fig. 1). Central to that panel are 43 stemmed clay pipes including a number of oversized specimen, which at that time make up a very important part of the assortment. The pipe bowls are arranged on the outside in an even row, the stems overlapping in the middle. Above the long pipes we see nine clay pipes with coiled stem. At the bottom the panel is divided into two compartments. On the left the half-length species are shown, on the right the more modern pipes with bent stem and lacquered end.

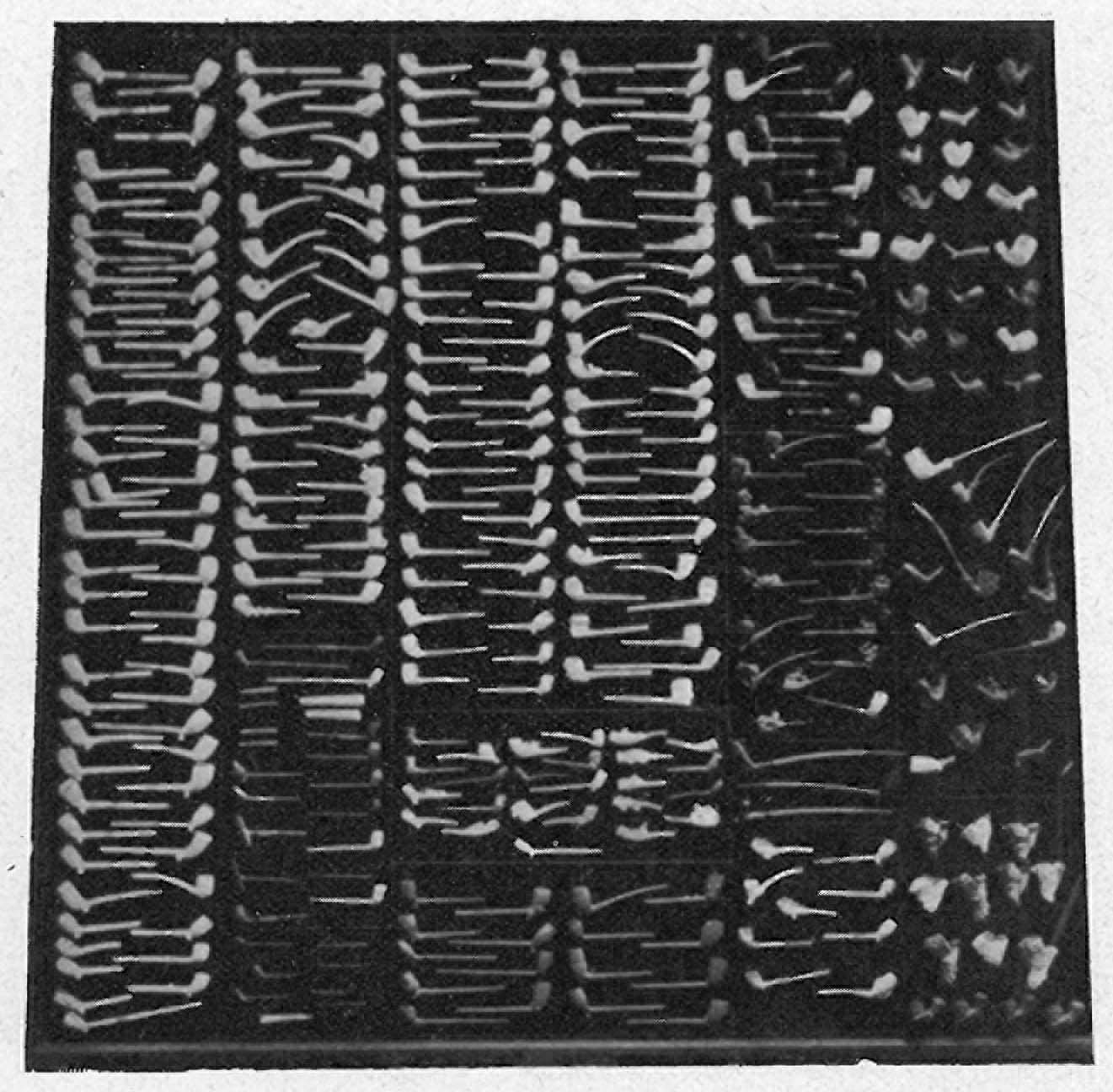

The photo of the panel for the short pipes is square. It is divided vertically into six rows on which the clay pipes are arranged from top to bottom (Fig. 2). These short stemmed pipe have almost the same order as in the factory catalogue and follow the so-called series classification. A series brings together pipes that require the same amount of labour and therefore the same pricing. There are series with almost undecorated pipes, full decorated ones, but also red pipes, cigar pipes, torrified clays or stub stemmed pipes. On this second board a total number of 317 clay pipes can be seen which brings the presented range to 397 shapes.

However, this second picture proves to be misleading. Upon closer inspection certain species, such as the large tobacco pipes with character portraits, appear to be missing. When we carefully check the series of short pipes, we conclude that this panel must have been one third larger in terms of size, but that this did not work out well in the layout of the magazine article. The photo was simply cut off. It is therefore not a square panel but a rectangle with a height of over one and a half meters and a width of almost two and a half meters. Ergo, the total range around the year 1900 was not 397 individual pipe shapes, but about 550 pieces.

Striking on both panels is that they are very compact, the pipes are close together. This is illustrative for the factory at that moment. At the end of the nineteenth century the pipe factory at Goedewaagen was bursting at the seams, which meant that all space needed to be economically exploited. The showroom, together with a small reception room, was located next to the office, right at the entrance of the building De Star along the Raam in Gouda. In that period the assortment was still very transparent. About 550 clay pipes with a very similar appearance that fit on two panels. In addition, the showroom housed a shelf with red earthenware pots, sufficient to show what was produced in the subsidiary sector.

Exhibiting the assortment was important for P. Goedewaagen & Sons. During factory visits, these two clearly arranged panels not only proudly presented the extend of the assortment, but also showed at one glance the options for the customer. At representations elsewhere one had to use a printed catalogue or other advertising material. Of course, that was far less convincing.

Goedewaagen’s showroom new style

When P. Goedewaagen & Sons moved from the Raam to the Jaagpad in 1909, it was time for a larger showroom. Their new factory was set up very spaciously, which applied for the showroom as well. The two product types each got their own room on the first floor of the main building, at the front where the external façade showed only blind niches. The showroom for pipes was on the left, measuring just four by five meters. On the other corner of the façade, looking out over the Nieuwe Vaart, there was a second showroom for the exhibit of the pottery. Between these two rooms was a reception area to greet new customers before a sales pitch was added in front of the assortment.

Now that the size of the showroom had been considerably enlarged, the layout was also revised. Along three walls three large panels were placed with an arrangement of all common pipes (Fig. 3). Since there was more space, the setup became much lighter. Each pipe was provided with a thin brass wire through the stem, with eyelets at the ends in order to be hanged on two corresponding brass nails. Arranged per series, the pipes gave a clear overview of the models, types, qualities and finishes. Thanks to the copper wire, the products could easily be handled and inspected for subsequent return.

The largest panel covered nearly the entire wall of the showroom and was more than two and a half meters wide and almost man-high. On the left side the layout was the same as that of the old panel with long and oversized pipes. Centrally these long pipes were presented from standard size length up to the one meter pipe. On the space above it were the clay pipes with coiled stem, underneath the medium lengths pipes together with the slightly bent pipes with lacquered stem ends. Compared to the old panel on the Raam, the range of long pipes had been drastically reduced, while the board itself had grown larger. The longest species were diminished from 43 to 23 in number, the twisted pipes from nine to four. The same applies to the medium length pipes that decreased from 19 to 8. Even the relatively modern pipes with lacquered stem ends reduced from nine to five. Downsizing the range, the manufacturer aimed at a more transparent production in the factory, but also at simplifying inventory management. Incidentally, around 1900 the long pipe became increasingly obsolete and the variety in marks and minimal bowl differences or stem thicknesses were too diffuse for the customer. Slimming down the assortment solved that problem.

The right part of this large panel was used to show short clay pipes (Fig. 4). These were grouped in a similar way as on the old board, more or less following the catalogue order. Here again six vertical rows were made with the difference that the pipes were placed more spaciously. As a result, a new panel had to be set up for a number of series such as the stub stemmed pipes. In the short pipes, too, we see changes in the supply that are mainly caused by an changing fashion in smoking. For example, cigar holders, now regarded as old-fashioned, had largely disappeared, instead the more modern cigarette pipes were added.

The two other panels on the side walls, opposite each other, were significantly narrower, slightly more than a meter wide. On the panel on the left wall the short pipe shapes continued. Here, for example, we see a nice variety of stub stemmed pipe bowls mounted with cherry wood stem, in white and luxurious gilded brown glaze. The right panel was intended for the slip cast ceramic pipes, a new production line introduced in 1909. The layout of this wall panel was probably renewed by 1920, when the range of ceramic pipes had become mature.

Central to the showroom was a large counter showcase with more recent slip cast ceramic pipes (Fig. 5). These plaster moulded products formed the luxurious part of Koninklijke Goedewaagen assortment. It is an oak cabinet with closed panels with pilasters at the front and a glass showcase on top. In the glass cabinet the exhibition changed from time to time paying attention to the novelties in the field of the ceramic pipe. The back of this display cabinet had doors or drawers to store additional assortment. All in all, the showroom was pretty chic and the manufacturer was proud of it. This is evident from the fact that the largest pipe panel was even screened with a curtain to protect the presentation against dust. In the thirties, when the room was painted over, this curtain disappeared.

A showroom of the same size was in use for the pottery. Here, the material was shown on shelves along three walls. In 1909, pottery consisted predominantly of the so-called Star pottery with a red or yellow-white shard in a limited number of shapes. It was finished with yellow-tinted or green lead glaze. This coarse earthenware was produced because the pipe pots could not be stacked in the kiln so that other material to be fired had to be produced to fill the cupola. After a few years, this range of ceramics will become more luxurious with sgraffito, coloured glaze and slip decorations.

Already at the time of the first arrangement, the pipe showroom gave a reflection of product development over multiple generations. The assortment was a grown ensemble that lived in a certain way and you could clearly see that. The wall panels containing the press moulded clay pipes, no longer changed in layout. The clay pipe pressed in a metal mould is a nineteenth century product, at the Jaagpad innovation to this category was no longer pursued. Not surprisingly, therefore, that these panels remained unchanged. However, until the Second World War, these panels stayed relatively up-to-date because the sale of press moulded clay pipes still formed a substantial part of the turnover. Many deliveries could even be made from stock. However, the range was drastically reduced in the 1930s, with the main reason that it was difficult to find pipe moulders and women to finish the products. Of course, sales were directed towards those products that could easily be made and yield the best profit margin.

Function of the showroom

In the showroom customers were received to present the products and to promote specific shapes. The showroom also served as inspiration for conversations about new designs and special assignments. On occasion, certain pipes were taken out of the showroom by staff to be put back later on. In case a pipe was given to a customer as a service, the same shape was later replaced by a new one. The showroom clearly housed a collection of use to stimulate turnover.

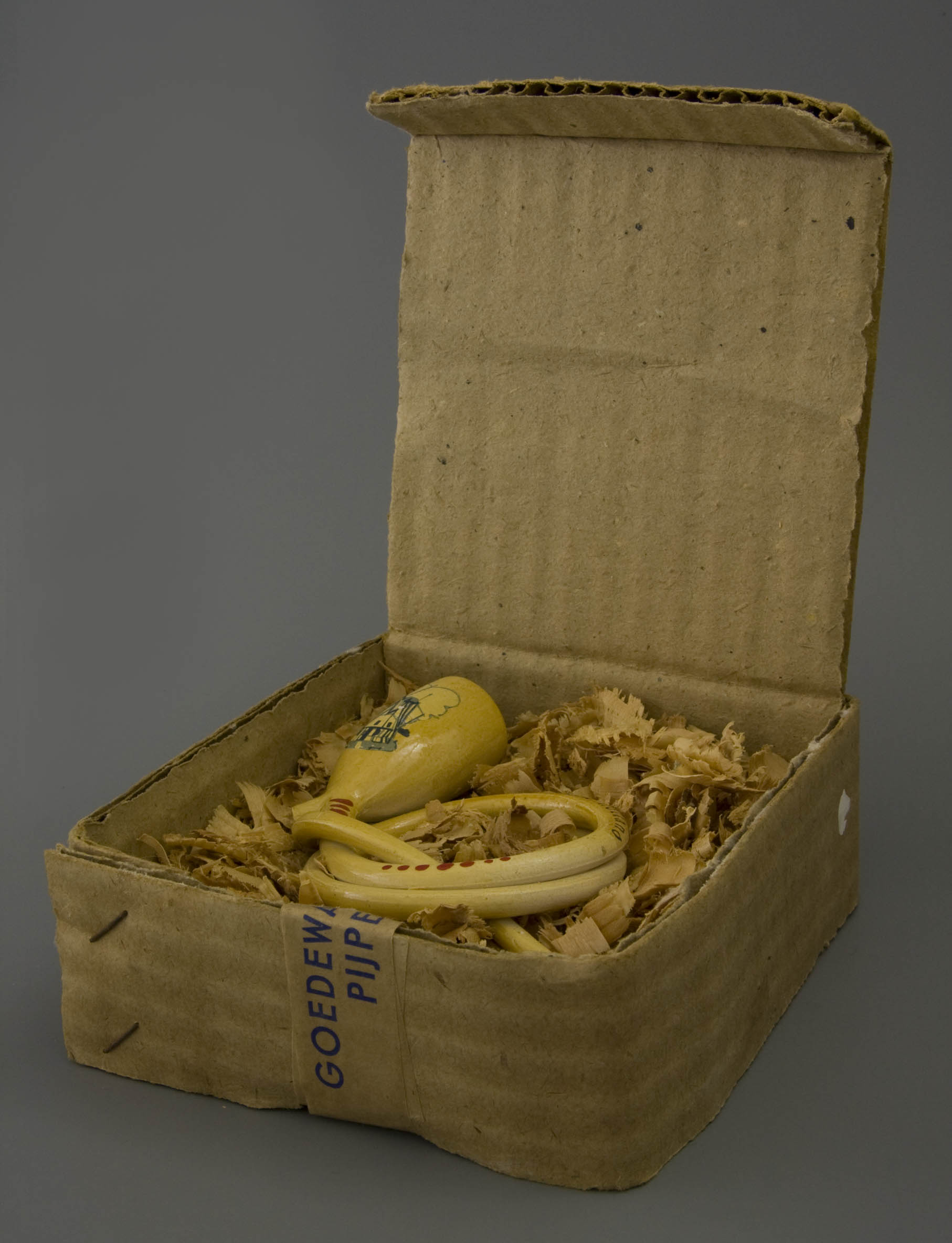

Also during group visits to the factory, the showroom was a rewarding place to welcome guests and convince them of the versatility of the factory product. From newspaper articles and reports from factory visits, we know that the showroom with its hundreds of pipe shapes always deeply impressed the guests. With the reception of groups of housewives and school children this was also the place to do souvenir sales. A table with merchandise displayed of all kinds of appropriate souvenirs items, neatly packed in boxes. Popular products were the coiled clay pipes, easy to carry in a cardboard box filled with wood-wool (Fig. 6). More luxurious were labelled gift boxes containing half a dozen miniature pipes (Fig. 7). A pipe smoker who really wanted something special could even buy a meter pipe in a protective wooden box. Alongside the pipes, souvenirs from the ceramic branch were gradually added, and from 1925 they even got more profitable than the pipes.

As already noted, the counter display cabinet central in the showroom was easy to adjust. In certain periods new merchandise was even put on top of this display case. This cabinet brought the latest production line, the ceramic pipe, to the attention. The mystery pipes and from 1921 also the baronite, were constantly evolving and the presentation in this showcase therefore changed. The luxury of this slip cast production line is also reflected in the packaging and advertising cards that were designed for this product. In this way design and appearance appealed to the critical, self-respecting pipe smoker with more money to spent.

The twentieth-century assortment of ceramic pipes on view in the showroom is for us more interesting and especially more learning than the press moulded clay pipe. This new production line was set up shortly before the year 1900 but only became lucrative from 1910 onwards when a streamlined production unit could be set up in the Nieuwe Fabriek (New Factory). Because of the greater luxury of the slip cast ceramic pipe, which also yielded a better profit margin, this product was really successful. The new product enabled a greater variety in design than the press moulded clay pipe, and moreover to be produced in smaller batches. For the future client, seeing the variation in shape, finish and painting was of great importance and the showroom collection gave this opportunity.

In the 1920s the factory also added a presentation of the new Baronite pipe. Unfortunately, no pictures have been saved from that panel, but this panel is mentioned in a later inventory list. The fact that the showroom was not only about the presentation of its own product proves another wall display cabinet that contains a remarkable collection of smoking pipes from all kinds of areas. A group of more than twenty Cameroon pipes was the most striking (Fig. 8). In the conversation focused on orders and sales these unexpected pipes could divert attention for a while and perpetuate the friendship between customer and manufacturer. Especially director Dirk Goedewaagen loved showing different types of smoking equipment and he was a master in setting up such a fascinating conversation.

After the Second World War, the press moulded pipe had definitively lost its economic importance. Only a few moulders and women finishers were left, who made nothing but the simple clay pipes for regular use. The extensive stock of press moulds was no longer used, so that the vast majority of pipe shapes could no longer be supplied. As a result, the panels in the showroom got more a curiosity value. The display no longer accurately reflected what the factory really produced or even what it was able to sell from old stock. So it no longer could provide an economic stimulus. In the post-war years, two panels with assorted pipes were added on which the well-running models - still partly out of the enormous new old stock - were brought together (Fig. 9). They are the so-called Römer panels, after the sales chef that introduced them. They show a fixed range of current tobacco pipes. With the installation of these two panels, the four old showroom panels actually turned into a kind of museum collection.

Showroom versus factory collection

In addition to the showroom collection that was on display, there was also a ‘factory collection’ of pipes at Koninklijke Goedewaagen. This indication may be misleading because it is not a collection in the current sense of the word: a group of objects, carefully assembled, based on well-considered selection. In fact it concerns a group of miscellaneous pipes in large variation, maybe better describes as obsolete trading goods. This includes residual lots that were no part of the current factory production.

This material included old and even antique pipes that were kept as curiosity, as an example of what existed somewhere in the world. In other cases, samples from competing companies or pipes brought in by customers that had to serve as an example for an order. Even residual stock from other factories could be found among them. For example, several lavishly decorated clay pipes purchased in 1880 at Duméril in Saint-Omer, were still available during the interbellum period. In short, the ‘factory collection’ contained an irregular mix of pipes that had accumulated unnoticed over time.

Such objects could be found all over the factory. The mould maker had some in his workshop. In the office and on the expedition, too, a batch of unregulated pipes could be found. In addition, all sorts of pipes were scattered over the production departments in the factory itself, often sample models and experimental pipes. This was hardly the case when the factory was still located along the Raam. The production of the press moulded clay pipe was much better structured and more systematic. Only when the production of the ceramic pipe starts, there is more time for experiments, production takes place in smaller series, resulting in more variation. None of this irregular material was considered to be the regular serial products fit for sales.

These unregulated items were in cardboard boxes, wooden cases and trays, sometimes without a clear purpose. Lack of time was often the reason that this material was lying around for a long time. The best succeeded specimens sooner or later ended up in the showroom as an example of what one could make. Others remained for years until after a clean-up a new destination was found, usually as an unsorted lot to a befriended customer. The size of these lots changed, so after clearing, this material was thinned out for sure, but growing immediately from that moment on. Sobriety and economy ensured that rigorous clean-up was not practiced.

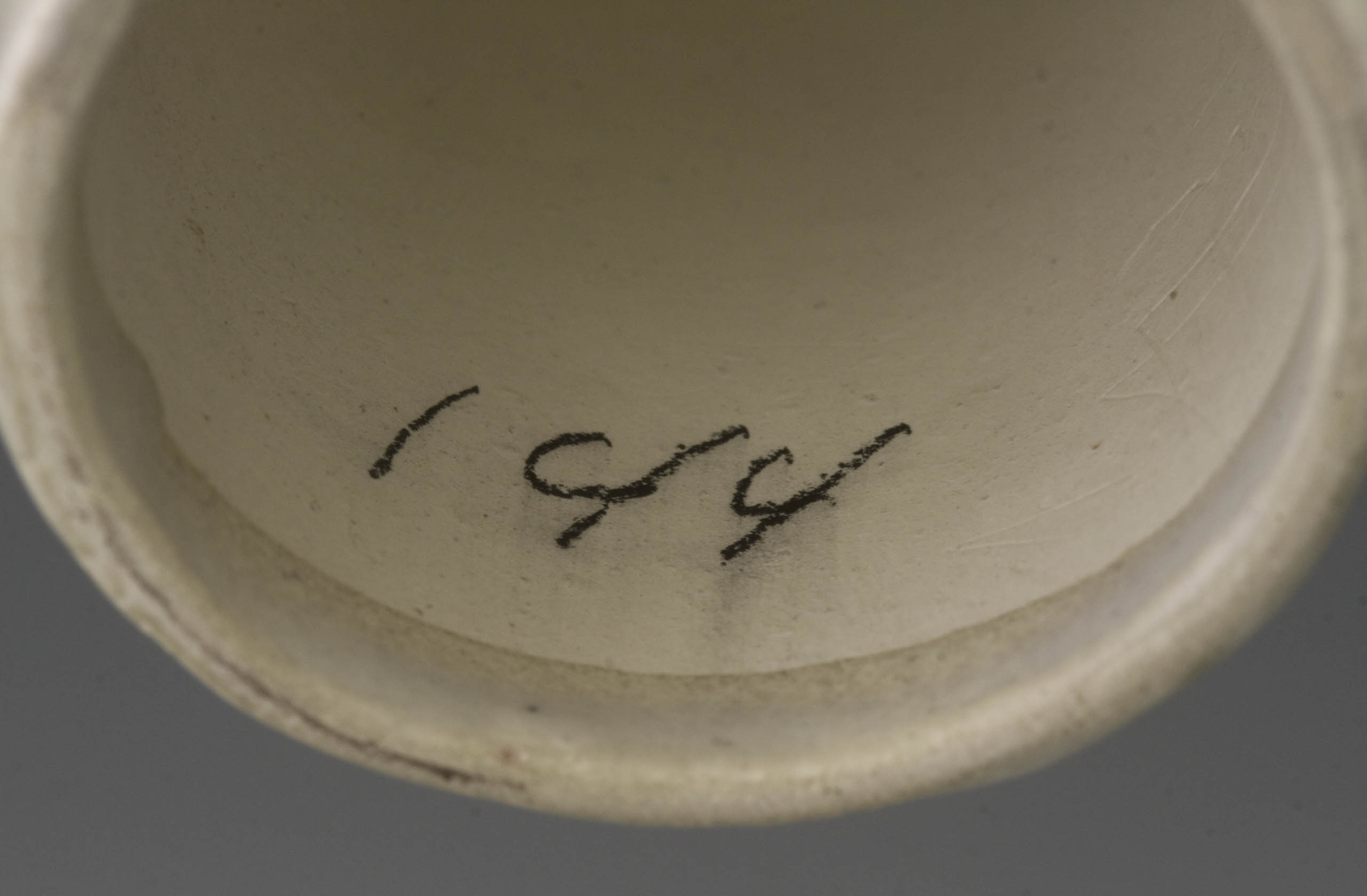

Among the factory collection we could also count the samples, pipes that were not in the showroom but in the warehouse. They were kept by the warehouse manager and handed over when the management or the salesmen asked for it. They were meant as a giveaway to provoke orders. With such pipes a shape number was always written in the bowl as a reference for reordering (Fig. 10). Many monster pipes will eventually end up between the lips of smokers and after a few times smoking the pencil number became invisible. The use at some French pipe factories to tie a string into the stem of samples in order to make smoking impossible is not known from Gouda.

Clearance of the showroom

In 1958 the management of Koninklijke Goedewaagen decides to close the traditional showroom of clay pipes. Curiously, hardly anything had changed in this room in nearly fifty years, and it was clear that the presentation no longer reflected the production of that moment. The reason for the dismantling of the showroom was change of policy, which included diminishing the range of pipes. On the occasion of a new pipe catalogue in 1958, the market supply of smoking equipment was drastically modified. The hundreds of cast pipe shapes from the beginning of that century were downsized to only four long and eleven short pipes or fifteen pieces in total! This change did not happen because of lack of orders, but was necessary because of an acute shortage of labour, especially to men for press moulding. This problem became apparent at the beginning of the 1920s, as a result of which the first downsizing already started at that time. In 1958 it was necessary to rigorously set a new course, changes had been delayed for too long.

When the showroom was closed down, the pipes from the panels were stored in a spacious chest in one of the attics of the factory. The woodwork of the panels was thrown away. A buyer was found for the large counter showcase. In this way the material archive of pipe manufacturing ended up casually in an attic with an uncertain future. Batches of the irregular pipes from the production departments were also added to the chest of showroom pipes. Incidentally, this action was taken in the light of a change from small-scale to massive pottery production that the factory was striving for. That mechanization required ample workrooms so that the reallocation of many production areas was logical.

In the newly decorated showroom, the emphasis was on the dinnerware and the other ceramics. The last fifteen shapes of press moulded pipes were given a modest place, together with a group of slip casted ceramic pipes. Nevertheless, these pipes remained a certain part of the turnover and were especially good for the name recognition of Koninklijke Goedewaagen. Between 1958 and 1963 the pipe warehouse was also sold out to use this space for production, as well as to generate money for machines and other investments.

This stock clearance ended up with the leading retailers in the pipe trade. The first known customer is Miss Plankeel, the last owner of the Wasmann company from Amsterdam. In 1960 she bought all kinds of unregulated goods from the old stocks, which were easily sold in her pipe store. In 1963, thanks to the presentation at a souvenir fair, several other tobacconists followed as customers. The most important customer was Van Eskert from Haarlem, who took over a substantial part of the remaining stock. I wrote a story about this earlier (Note 3).

A third major buyer was the tobacconist and cigar retailer Van Stro at the Bloemenmarkt (Flower Market) in Amsterdam. He bought what Van Eskert had rejected. Later, by experimenting with glaze himself, and adding his own stem mountings, however historically incorrect, he brought more variety in the assortment than ever before. Other Dutch tobacco retailers took over smaller quantities, so these lots left hardly any trace. For example, a cigar shop in Hoorn purchased a batch of pipes with souvenir pictures, that proved to be difficult to sell. Furthermore, material left the factory as a gift to regular buyers, but it also happened quite often that pipes were taken away by workmen. This meant the residual stock gradually thinned out.

The start of a second branch in Nieuw Buinen in 1963 was in line with the new course of Koninklijke Goedewaagen. Due to lack of labour force in Gouda, serial production was relocated to Drenthe. With the so-called grote plan (large project), the management decided to liquidate the Gouda site and in phases the factory buildings at the Jaagpad was cleared. The showroom moved again to be housed with the office in the attic of the old kiln building, furthest from the Nieuwe Vaart. Because there was hardly any room left there, the last curiosities were given to anyone who wanted. When the factory building at the Jaagpad was finally sold, there was nothing left of the old showroom material and the samples of ceramic pipes. In 1977 a new office was set up at the Wachtelstreet, again together with a showroom. Meanwhile, the so-called modern Delft pottery dominated and the tobacco pipe only occupied an ancillary position. At that stage only slip cast ceramic pipes were presented, the press moulded product had finally disappeared. Historical material was no longer to be found at the Wachtelstreet.

What remains of the showroom

It is now almost sixty years ago that the old factory showroom was liquidated. It has become time to make up the balance of the material that has been preserved from this showroom. At the time the inventory consisted of three large wall panels with four hundred press moulded pipes. In addition, we had the flat counter display case with another two hundred slip cast ceramic pipes, supplemented with a few hundred items in later years. In its best days the showroom therefore contained a collection of Goedewaagen pipes of at least eight hundred pieces.

In addition to the showroom models, there are objects from the so-called factory collection, consisting of experimental pipes, curiosities and old objects in a much larger variety. This also involves a batch of many hundreds of items. Furthermore, we are unable to estimate the number of sample pipes that were still in the factory in the 1950s. For sure all that material found a re-use, where possible as merchandise for resale, otherwise as giveaways or in a less favourable case disappeared in the pockets of employees.

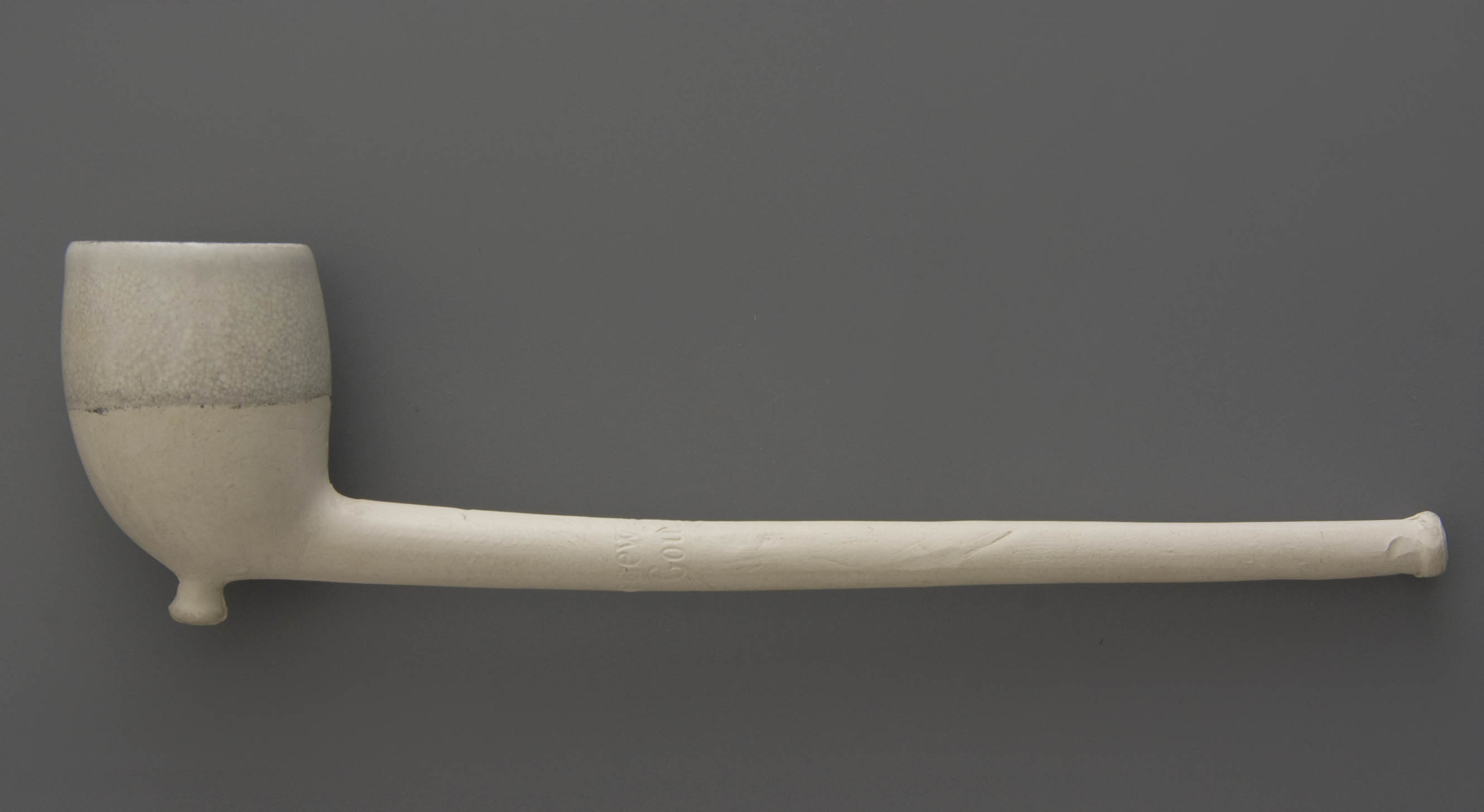

To make a distinction nowadays at the pipes of Goedewaagen between showroom models, the factory collection and sample pipes is not easy. Most of the pipes from the showroom are not recognizable because the brass wires have been cut away. To our knowledge, only four pipes completely survived with the original wire with which they were attached to the panels in the display room (Fig. 11). Four pieces out of four hundred copies means only one percent. Still, there are certainly more pipes from that category preserved, but because the collectors removed the wires, they are now no longer recognizable. For example, the former pipe collection of Douwe Egberts held countless such pipes with brass wires, but they all have been removed.

Especially from the so-called factory collection numerous pipes were taken by employees, sometimes even by people from outside. As already noted, the large chest with showroom shapes and experimental pieces was plundered by many different persons between 1958 and 1963. In retrospective we can form a picture of the people who made their choice. The plumber of the Koninklijke Goedewaagen factory was the first to discover this chest with showroom material in the attic and made a choice after every roof repair. That happened until the year 1963. In doing so he built up his own pipe collection that he sold not much later. An administrative employee from the factory also found this source and took his part. But certainly there were more people who have remained unknown. One employee from Goedewaagen was so keen to take a beautiful set of Duméril pipes. They were samples as part of the large purchase in the year 1880 in Saint-Omer. These special pipes were shown to me in the 1980’s during a determination day in Gouda but the owner did not want to make himself known. They are still lying dormant somewhere in a box. In five years, the testimonies of two generations of product development were dispersed and disappeared from sight.

From the third category, the sample pipes, which left the factory as a free example and carry a shape number in the bowl, quite a lot are left. They are especially important because they indicate the shape numbers with certainty, which can sometimes no longer be determined in any other way. Another characteristic is that they are unused, even though a single specimen could have become discoloured by hanging in a smoky room for years. The recognizable pencil handwriting (see Fig. 8) shows that for years it was the same employee who provided these pipes with a number which gives an extra point of recognition. With a few exceptions.

Koninklijke Goedewaagen made an important donation of these sample pipes to De Moriaan museum in Gouda. That happened already in 1938, the year of opening, at the request of curator Bert Helbers, who wanted to document the last Gouda pipe factories. Even those pipes carry the well-known shape number in the bowl in the old-fashioned pencil writing. The collection donated at that time was selected directly from the warehouse stock, at the moment the pipe warehouse still functioned. Interestingly, they prove what was still in stock at that time. Unfortunately, for an unclear reason, the Gouda museum was barely endowed with long pipes.

The showroom collection in the Amsterdam Pipe Museum

Over the past forty years the Amsterdam Pipe Museum has committed itself to collect an overview of pipes from Koninklijke Goedewaagen firm. This collection is made up of incidental purchases, but due to years of attention, this sub-collection has become the most authoritative. Thanks to sources of different nature, the museum can now give a pretty complete picture of the production of Goedewaagen over the past hundred years. This reference collection consists of showroom models, pipes from the factory collection and samples. This material was subsequently supplemented with pipes from residual stocks from cigar shops and examples from private ownership. The basis for this showroom collection is primarily the diversity, obviously aimed at optimal quality and preferably not discoloured. This cannot be assured with pipes from the antique trade and from the flea market.

Since our collection of Goedewaagen pipes started in 1970, the chest with showroom pipes from the attic proved to be an important source for our museum, albeit indirectly. In the 1970s, Niels Augustin started to sell his Goedewaagen collection, that had derived from Goedewaagen's plumber, already reported. Those pipes came in two stage from the source into our collection. The clay pipes from the museum of Douwe Egberts were purchased from Miss Plankeel around 1960, but only found a place in our collection in 2003 (Fig. 12). With the passage of the years the material came from the third or even the fourth hand, but even then the pedigree is still traceable. In addition, trade and collectors have both been sources.

People who bought from Van Eskert and whose collection later came into our museum are numerous. From larger collections such as those from Niels Augustin and Fred Tymstra, respectively 48 and 79 copies were obtained, a smaller addition being that of the heirs of Ivo Tribioli with 11 pieces (Fig. 13). An unknown collector from Rotterdam, whose pipes were sold out in 1984 through an antique dealer in Brussels, accounted for 44 shapes. Sources from the third hand such as the collection of Stan Konings in the auction at Mak van Waay in Amsterdam yielded 28 acquisitions.

The reconstruction of a factory overview of slip cast ceramic pipes was significantly more difficult. In general, little attention was paid to the ceramic pipe because it was too modern for the collector. In the case of the Goedewaagen donation to museum De Moriaan in 1938, for example, this kind of material was not included. We have been able to make various important purchases for our collection of ceramic pipes. As early as 1976, I encountered all kinds of rare showroom pipes and experimental pipes when the son of an employee brought these to an antique shop in Dordrecht. It was only in 2006 that the bulk of that material was put on the market via a thrift store (Fig. 14).

A few other purchases have ensured that we now have a proper overview collection of ceramic pipes. Straight from the Goedewaagen factory comes a group of pipes, so-called special orders made on request, which served as an example for new orders in the twenties and thirties (Fig. 15). They remained unnoticed in a drawer of an antique cupboard for about forty years. An important addition is the gift of Tobie Goedewaagen in 1977, who donated a current overview of the products then still for sale. This included panaches, the music series and some baronite pipes (Fig. 16). Meanwhile, these pipes are more than a generation old, showing what the latest Goedewaagen products looked like.

In addition to large purchases directly from the source, there are incidental finds. The pipe collector Mommersteeg from 's-Hertogenbosch sold a number of test and showroom pipes in 1976 that he had previously purchased from Niels Augustin (Fig. 17). The Leiden collector Bob Slingeland had all kinds of irregular Goedewaagen pipes through an employee at Goedewaagen that we took over in 1987. These are examples of pipes spread through time and space that were acquired from the umpteenth hand. An unexpected addition to this reference collection were some early samples of Goedewaagen found at a briar factory in Saint-Claude (Fig. 18). These products had remained there in the factory archive for generations, as pipes from other factories were preserved at Goedewaagen.

By doing provenance research and consistently recording the results in the collection database of the Amsterdam Pipe Museum, it has now become clear which part of the showroom or factory collection of Goedewaagen has been preserved as a museum object. The total collection Goedewaagen pipes in our museum is just over two thousand pieces. Ceramic pipes make less than a third of this sub-collection. The role of Van Eskert is very important in the composition of our collection. A total of 420 copies were bought directly and indirectly from their shop in Haarlem, largely press moulded pipes and only 33 slip cast pipes. So this makes up twenty percent of the sub-collection. By other roads, another three hundred pipes came verifiably from the factory collections. This means that the Amsterdam Pipe Museum conserves around 700 objects from the former factory property of Goedewaagen. In 2015, the expansion of the Goedewaagen pipes sub-collection virtually came to a standstill. In the coming years, there may be a pipe a year. The collection has reached its maximum completeness.

In conclusion

This article deals with the showroom of Koninklijke Goedewaagen factory in its development and downturn over time. It shows how the manufacturer presented his product in a showroom and how that changed over the years. It also deals with the shifts in the assortment. Furthermore, the elimination of the showroom and the sale of its content is treated until the remaining material got a new, partly museological destination. It does not define the pipe in form or use, but instead according to origin. It distinguishes between a regular commodity item versus show models or archive copies. Pipes that left the factory as a serial product along the appropriate ways are therefore not included in this article.

Thanks to photographs we know how the showroom of Koninklijke Goedewaagen in Gouda looked like. We know in detail how the factory presented their products. Furthermore, it became clear what the role of this showroom was, until the moment of dismantling in 1958. Subsequently, an inventory was made of what happened to that material and along which ways a part of the factory property was given a new life as a museum object.

From the moment the Goedewaagen pipe has my attention, I have been working to reconstruct the factory history in order to map the development of the pipe. This includes the assembly and documentation of a collection of pipes from specifically this factory. Subsequently, we did provenance research in recent years to record the pedigree of these objects more carefully. This article is the result. In contrast to most of the sub-collections, the pipes of Koninklijke Goedewaagen could still be given an origin with certainty. This established knowledge is the basis for later interpretation of the objects and form a proven reference for all scattered pipes by Goedewaagen.

It may seem unjust that the Koninklijke Goedewaagen pipe factory has received a disproportionate amount of attention in my investigations into Gouda pipes. In addition to book publications, there are multiple articles. There is, however, a clear reason for this. This factory has become exemplary for the operation of the factory company in general because both products and archive material have been preserved. Since there is virtually nothing left of other factories, we can hardly reconstruct the history, let alone write on it.

© Don Duco, Amsterdam Pipe Museum, Amsterdam - the Netherlands, 2015

Illustrations

- Showroom panel with the longest types of pipes, including over lengths, coiled stems and lacquer stem ends. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, 1906 or earlier.

From: Eigen Haard, 1906 - Showroom panel with short clay pipes, the right side of the photo cut off. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, 1906 or earlier.

From: Eigen Haard, 1906 - Photo of the showroom of Koninklijke Goedewaagen at the Jaagpad in Gouda, 1945-1955.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 10.014l - Photo of the section of short pipes in the showroom of Koninklijke Goedewaagen, Gouda, 1925-1940.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum, documentation - Photo showroom Goedewaagen with the large table showcase in the centre, 1930-1940.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum, documentation - Lacquered pipe with coiled stem with picture of a Dutch windmill, in cardboard box. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, 1920-1940.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 5.842b - Miniature gift box with printed label containing long pipes in miniature. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, shape 0000, 1920-1930.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 13.659 - Tobacco pipe with African mask used for animation of sales talks at Koninklijke Goedewaagen. Cameroon, Grasslands, 1900-1930.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 22.160 - Press photo of the so-called Römer panel with assortment of press moulded clays and slip cast ceramic pipes. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, 1958-1962.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.253 - Clay pipe with handwritten shape number in the bowl. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 144, 1910-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.655

- Tobacco pipe still with an original brass wire for attaching on the showroom panel. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, 1900-1915.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 14.295

- Cigar holder with dog, torrified and gilded clay. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 567, 1895-1910.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 4.170c

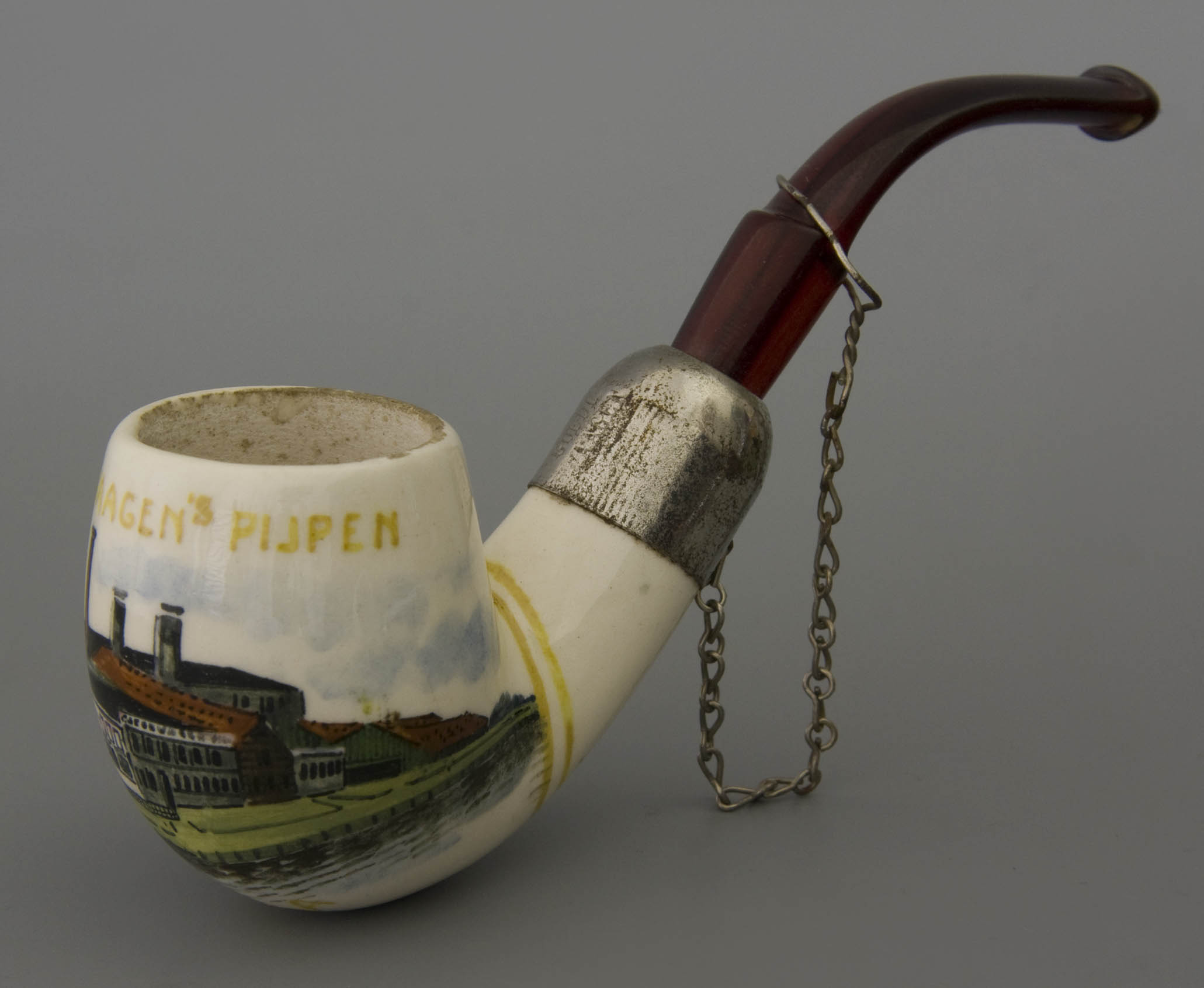

- Clay pipe with glaze band round the bowl opening from the Ivo Triboli collection. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 75, 1900-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 21.657

- Tobacco pipe with full clay stem in slip cast technique, painted winter landscape. Gouda, Firm P. Goedewaagen & Sons, shape 713, 1910-1920.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 17.786

- Tobacco pipe in baronite version with moose and letter word. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, 1925-1935.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 6.524b

- Packaging box with modern slip cast ceramic pipes of the music series. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, 1975.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 10.268bis

- Gouda tobacco pipe with a Gouda pottery painting (plateel) with advertising for the factory of tobacco pipes. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, shape 683, 1912-1918.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 5.769

- Baronite tobacco pipe with souvenir illustrations from the Comoy-David sample collection in Saint-Claude. Gouda, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, shape 762, 1930-1940.

Amsterdam Pipe Museum APM 18.597

Notes

- D.H. Duco, Koninklijke Goedewaagen, een veelzijdig ceramisch bedrijf, Leiden, 1999, p 63, ill. 79 and p. 132, ill. 206.

- S. Abrahams, 'Van Gouwenaars', Eigen Haard, XXXII, 1906, p 412.

- Don Duco, 'Interessante rekeningen van een uitverkochte fabrieksvoorraad', Amsterdam, 2013.