The corncob pipe, Missouri meerschaum or barnyard briar

Auteur:

Don Duco

Original Title:

De maïskolfpijp, Missouri meerschaum of barnyard briar

Année de publication:

2008

Éditeur:

Pijpenkabinet Foundation

Description :

History of the corncob pipe from its origin to present times, overview of the different types of corncob pipes.

Going through books on pipes the corncob pipe is seldom a subject of serious attention. Not surprising because the corncob is one of the humblest smoking pipes, almost a disposable item. However, the product is interesting enough to dedicate an article to. Firstly, it is a nostalgic item that, despite of its simplicity and material yet has proven its right of existence. Furthermore, it is a product from an industry that has a history of over 130 years. Thanks to smart marketing the corncob gained a worldwide distribution. Finally, the corncob pipe is one of the few typical American pipes that makes an ideal combination with the tobacco, also from American origin. This article deals with the history of the corncob and informs about the manufacturing method, the types, shapes and smoking qualities.

History

Farmers boys in the United States often smoked the silky leaves of the corncob as a surrogate for tobacco and the idea to use the hard cob of the corn to make a pipe is not too farfetched. Nevertheless the name of the man who was the first to produce corncob pipes survived: John Schranke, a farmer from Missouri (Note 1). Like many other farmers in the U.S. his livelihood was the cultivation of corn. One day in 1872 he brought a bag of corncobs to the wood turner Henry Tibbe who lived in his neighbourhood (Note 2). He asked the craftsman whether he could turn the cobs into pipe bowls and add a wooden or reed stem. Tibbe did what he was asked, he even kept some of the pipe bowls for himself and displayed them in his shop window. To his surprise Tibbe sold them rather quickly.

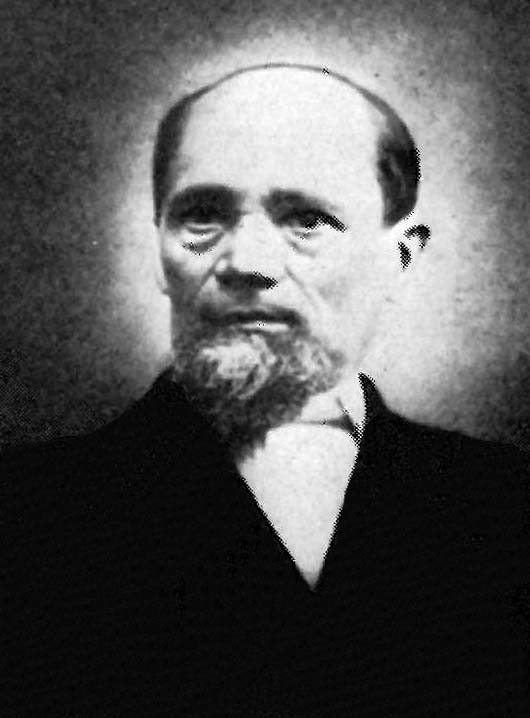

Wood turner Henry Tibbe was officially named Hendrik Tibbe and came over to America some years before from the Dutch town of Enschede (Fig. 1). There in the area called Achterhoek, he ran a company in simple furniture which he sold to the local population employed in the textile industry. An unlucky coincidence in May 1862 lead to a great fire in Enschede, where both the house and the workshop of Tibbe burnt down. This loss made him to leave Enschede, and move to America together with his wife, his eight year old son Anton and his brother Fritz. They settled in Washington, Missouri. In 1869 he founded together with his brother and son a similar workshop as they ran in Enschede. They continued the turning of wood for furniture and other practical purposes.

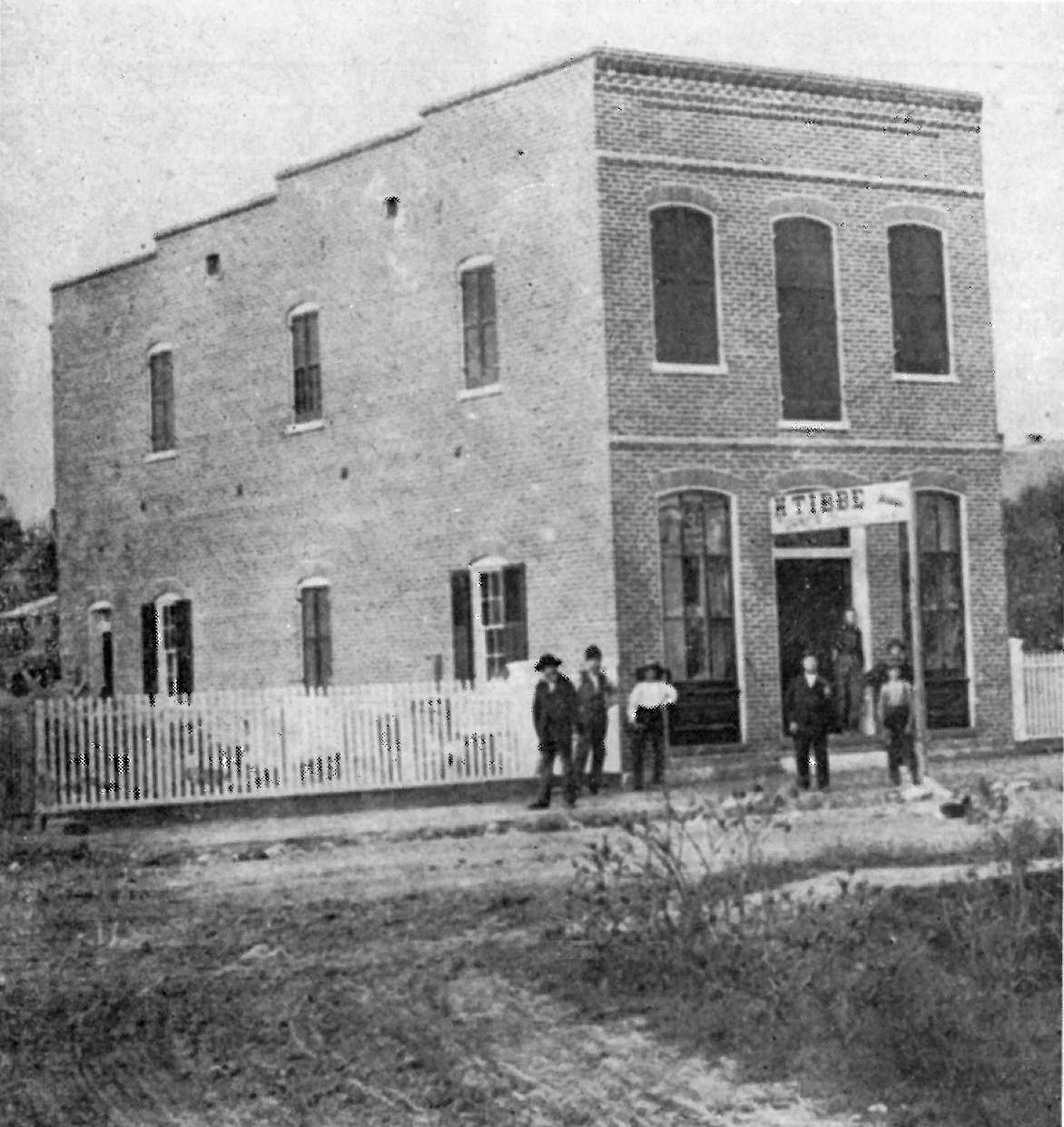

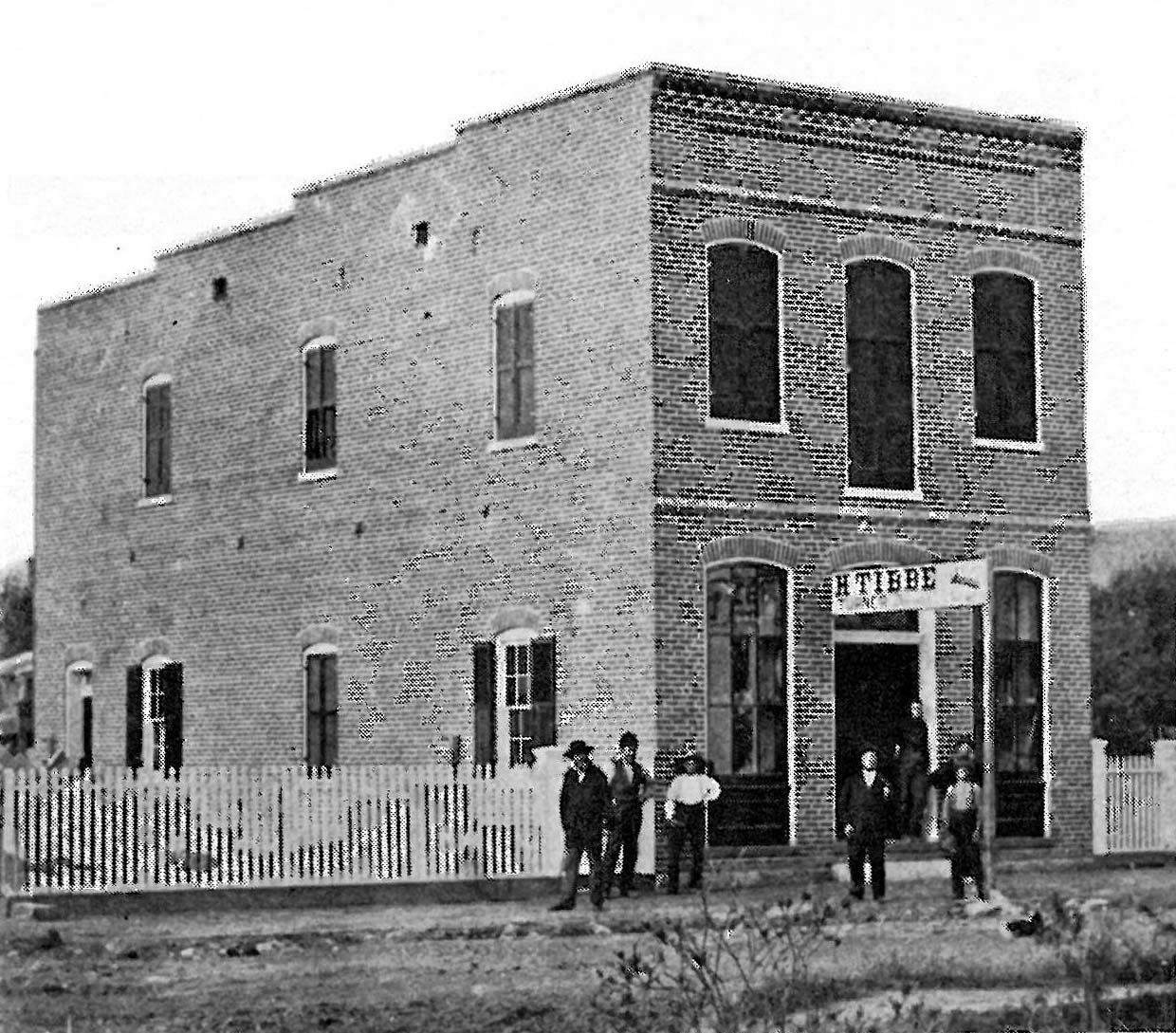

At the time Tibbe turned the first pipe bowl on his workbench, he will not have expected that due to the quick sale a new specialization was born. The sales increased and Tibbe soon streamlined the production. Five years later, in 1877, Tibbe had to move to a larger building (Fig. 2). Since that building originally housed a forge, the existing steam engine enabled him to built up a real factory with machine-made production . Simultaneously son Anton entered the business as a partner and the company was renamed H. Tibbe & Son. Another ten years later, in 1887, father and son exhibited their corncob pipes in Brussels. They advertised as Missouri Meerschaum Company, subtitled as mass producers of barnyard briars (Note 3). The foundation for a successful business was laid.

Materials and production

The material for the corncob pipe is the butt of a special kind of white maize, which is called collier seed and is especially grown in the state of Missouri. With some exaggeration the pipes were named Missouri meerschaum pipes, the addition meerschaum referring to the light weight and high porosity of the material. When the fruit is ripe and the corn is processed, the core of the fruit remains as a residual product. This must be kept for several years in order to dry before it can be processed into a pipe. The production starts by cutting the cob, size wise suitable for one to three pipe bowls. Thereafter, the sawn-off pieces are placed in a turning lathe, to drill the inside. Finally, on the side a small hole is drilled to insert a separate stem.

Initially, the production of corncob pipes is limited because the lathe was powered by hand, being a large flywheel for smooth running. All the employees in Tibbe's factory were obliged to turn the flywheel for an hour each on his turn. The turned pipe bowls had a rough exterior, did not look nice and felt unpleasant. To upgrade them Tibbe needed a filler. Thanks to the help of a good friend, the German Ludwig Münch who owned a drugstore in Washington, Tibbe experimented with plaster. When this was applied and dried, the pipe bowl could be sanded and finally smoothened with shellac. The plaster was not only an aesthetic application, it also stimulated the absorption of the moisture to get a better taste. On July 6, 1878 Tibbe got a patent on this invention.

After turning of the bowls they were scorched with gas burners in order to make the bowls stronger. Especially the sanding of the products made the work in the factory extremely dirty, while the smell of burning gas was not really pleasant either. In short, the corncob pipes works certainly couldn't offer employees pleasant working conditions.

Development of the factory

When in 1883 the pipe works entered a new and again larger building, the sales could also be increased and therefore an advertising campaign was started. Soon the corncob pipe was known across America and the city of Washington, Missouri became the centre of production. The factory was of great importance for the town itself. The activity not only secured a steady income for many workers, it also brought prosperity to the farmers, who were about to plant special corn for the production of these pipes. Son Anton supported the initiative for a power station, which enabled him to speed up the production to meet the growing demand. At the same time the electricity brought more comfort for residents of Washington, especially when lighting of streets and houses was introduced. Moreover, this led to the installation of telephone connections. This switchboard was housed in the pipe factory and proved to be a rewarding stimulus for the sale of the product.

The four children of Tibbe's son Anton, with the names Anton, Henry, Madeline and Jon Tibbe continue the firm, but instead of being directors they became shareholders. In 1912 the ownership goes to Edmund Henry Otto and finally the factory became a limited company under the name Buescher Corn Cob Pipe Company. In 1941 George Buescher was elected chairman of the company. He was a merchant in all sorts of pipes and expanded the production line with the so-called hickory pipes, made out of walnut. To achieve this, he bought the firm Pugh Co. Pipe from Bowling Green, Missouri, a company established in 1894. They initiated the Peerless Hickory Pipe that was famous all over America. During the war years, the harvest of corn was so scarce that Buescher was obliged to make millions of walnut pipes. After the war the production of these pipes continued under the name Ozark Sweet Hickory Pipes. Later Buescher also gained the market with tobacco pipes made out of cherry wood.

In order to secure the raw material for the pipes Buescher asked Dr. Markus Zuber of the University of Missouri in 1946 to supervise the cultivation of corn. The aim was to develop a higher quality cob, better suitable for the production of pipes. This plant breeding improved the quality of the cob in such a way that the structure became more ligneous, and moreover, the diameter increased a little. Simultaneously, the original coloured corn was transformed into white maize that was much in demand, for instance for producing tortillas. From that moment the pipe manufacturer provided the seed to the growers to ensure that the farmers came up with the right quality of cobs. Interesting enough the demand for corn cobs resulted sometimes in a higher price for the cob than for the corn.

In the sixties the Buescher Company is the world's largest producer of corncob pipes, pipes of sweet hickory and cherry wood (Fig. 11). The company produced daily between twelve and seventeen thousand pipes in about seventy different shapes. The production is exported to 57 countries and distributed in no less than 7,000 outlets. Customers were found in Cyprus, Saudi Arabia, Tanzania, and in Tokyo. During that time, the corncob pipe became a kind of anti-status article that was sold alongside the most luxurious products of briar and meerschaum. The factory for corncob pipes is then still owned by the Otto family, father Steve and son Carl Otto.

The success of the corncob pipe is illustrated by the fact that even in 1990 the factory employed 50 men with a daily production that exceeds the seven thousand pipes. This figure might be a little too flattering, as is often the case in promotion brochures. However, the production is at that time fully mechanized so that per employee per day an average of 140 pipes are made, which seems to be a feasible number. The corncobs are still widely sold, although the choice in shapes is greatly reduced.

Appearance and evolution

Quite understandably Missouri was soon named the world's corncob capital. However, the designation Missouri meerschaum pipe is very flattering for a product that is actually made from corn waste. Although the naming of the pipes was an euphemistic nickname, many customers will have chosen this particular pipe because of the attractive name. Its low price and good comfort when smoked characterized by a slightly sweet taste, established its popularity. Another cheerful name for the corncob is barnyard briar, a name that symbolizes the rural America. The local press claims that a Missouri corncob pipe is the best for tasting local Missouri tobacco, giving the smoker a taste that is so mild that all his concerns and issues disappear like snow in the sun. But the positive allegations go further, since the area of the corncob is said to be so healthy that Americans born and raised there are on average bigger and stronger than any other American. In conclusion, local pride goes hand in hand with fierce chauvinism.

For a proper variation in bowl sizes the cobs in the factory were first sorted by size. High bowls were made from a whole cob, sometimes a part is sawn of to be used for a smaller bowl. Subsequently, after the turning of the bowl quality check followed. The most perfect cobs were meant for the best finished pipes, while irregular bowls were used for the cheapest products. From the leftovers miniature pipes and novelties were made. Initially, the pipe bowls were quite high (Figs. 3, 4), named two of a cob pipes. They were fitted with a single piece cane stem, which was popular by other local American pipe makers as well. In the beginning the pipe had no distinct mouth piece.

The appearance of the pipe is greatly depending on the shape of the cob. The most characteristic shape is the Mac, a high cylindrical bowl with a long straight stem. This model is named after General MacArthur, who preferred this pipe style (Fig. 8). Since 1930, many pipe bowls were slightly barrel-shaped, named Legend (Fig. 7). It is a so-called three-in-a-cob pipe, so much smaller and less elegant having a strong resemblance to the conventional briar pipe. Of course, on the lathe also more cylindrical pipe bowls were made, such as the Washington (Fig. 6) or even conical pipe models. As a proof of being able to manufacture non- ordinary styles , a flamboyant corncob pipe with a long s-shaped cane stem was made (Fig. 5). This luxurious pipe has a wonderful regular corncob that is carefully filled in with plaster, afterwards covered with lacquer for a polished finish.

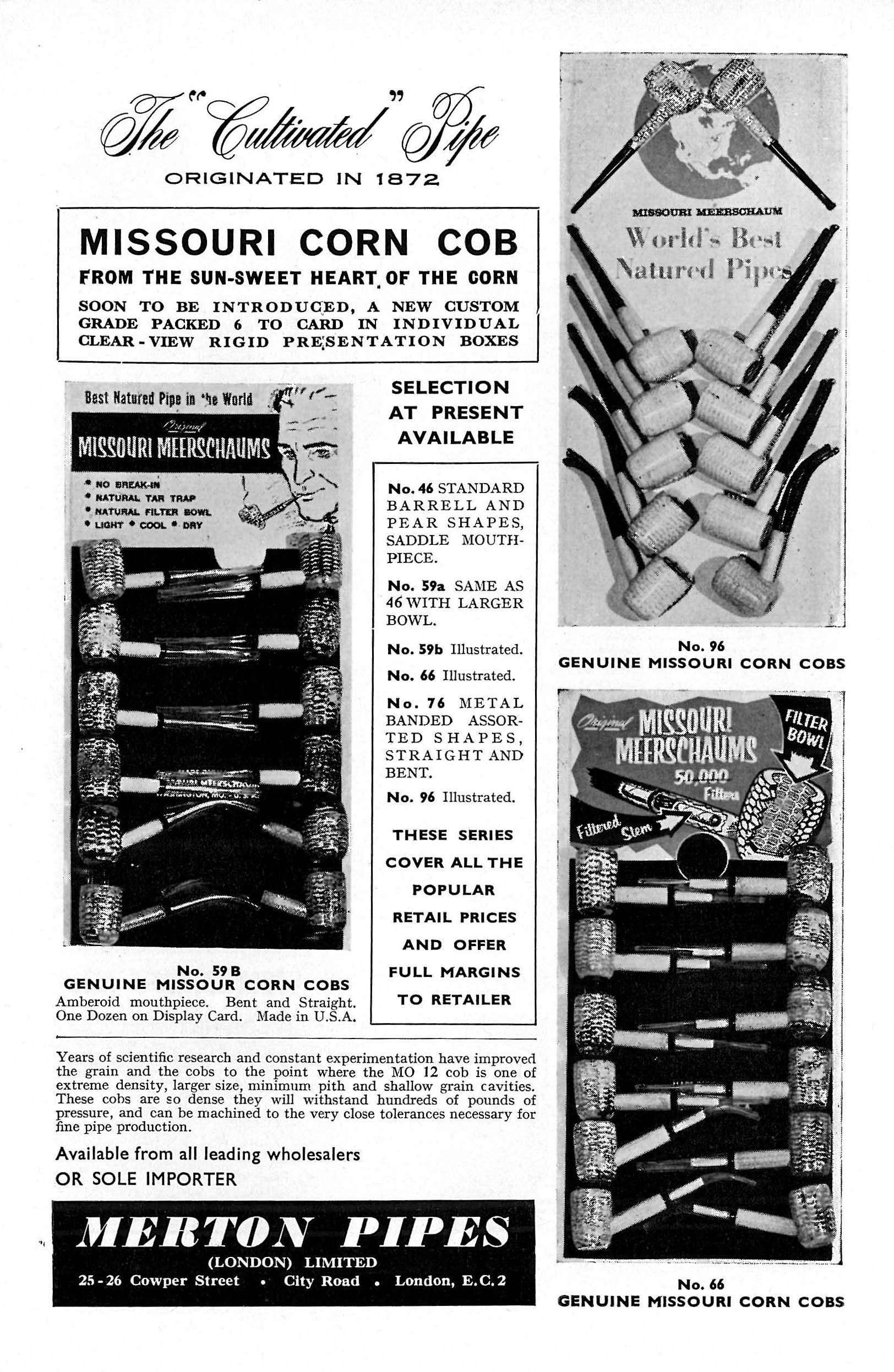

When, however, large series were manufactured, the average quality went down. The cheapest is the nature cob with rough exterior without gypsum finish (Fig. 6). This natural finish provides the best moisture transport. The vast majority of these pipes are sold per dozen, straight and bent shapes alternating, mounted on a cardboard pasteboard with printed advertising as a complete shop display(Fig. 13ab). In the fifties and sixties, the pipes were fixed on pasteboard by the dozen with a drawstring or elastic band, in later times the card was shrink-wrapped in its entirety.

As noted earlier, originally the stem of the corncob pipe was made of reed. A later variety is a stem made in morello wood. Another choice is a stem of corncob timber. This material offers the best esthetical unity with the pipe bowl, but unfortunately this material is not very strong. Later, a light wood was used embellished with a corncob print enhancing the unity between bowl and stem (Fig. 7).

Nowadays, the stem of the corncob pipe gives the best opportunity to date the pipe, eventually in combination with an added fitting. An evolution can clearly be distinguished. The oldest forms of reed are usually straight, though a rare fancy bent stem was already discussed. The contrast between the stout bowl and the thin stem gives the pipe a delicate silhouette and a wonderful balance. In the 1930s, the thicker stem was introduced, sometimes in cob wood, but usually of a light wood type. The mouthpiece could now be turned slimmer with a lip. Fitted in that way the corncob pipe gets to resemble the briar pipe, especially when the stem is finished with a black nylon or plastic mouth piece.

In other cases the black mouthpiece was replaced by a yellowish transparent plastic mouthpiece. Especially the amber coloured mouthpieces do honour to the name Missouri meerschaum, they were copied from the real amber mouthpiece of the expensive genuine meerschaum pipes. A luxurious addition is a small metal band around the stem, being functional as well since it protects the wood from splitting. In this way, the durability of the stem grew to such an extent that it survived the bowl. After a certain period of use the pipe inevitably will burn through at the bottom of the bowl, since maize timber is a soft and burnable material.

Sometimes, the stem is made of bamboo as seen with a fancy model with blackened top and extra shine (Fig. 9). This dark coloured bowl rim is another inspiration taken from the meerschaum pipe in calcined finish. The corncob pipes are products of the prevailing fashion in other materials, as we can see in a rage of the sixties: the introduction of a paper filter in the stem.

A weak point of the corncob pipe is the bottom of the bowl that quickly burns out. Unwillingly the stem can catch a fire that results in an extremely unpleasant taste for the smoker. In some cases, therefore, a bottom of a harder sort of wood is added, so that the pipe burns out less easily. In Germany, the corncob pipe is sold with a special coin with a hole in it, that was placed above the place where the stem is inserted in the bowl. Apart from a longer life this had its negative effect on the taste of the pipe.

Users qualities

The opinions on the quality of the corncob pipe as a smoking pipe varies widely. Two features make the cob corns ideal for a pipe: the material is lightweight and has an absorbent nature. The soft wood adds a pinch of sweet taste to the burning tobacco and therefore results in a pleasant aroma. The slogan used by the promotion of the pipes is: sun-sweet made of the heart of the cob, a qualification that makes a smoker-to-be curious.

The disadvantage however is that the corn does not absorb over a long period of time and when the wood becomes saturated, the pipe starts tasting sour or bitter. When the bitter taste pervades it is time to replace the pipe for a fresh one. Of course its life time depends on the type of tobacco smoked and the way of smoking. Drawing harder from a pipe results in a quicker need for replacement. The interim drying of the pipe overnight remains a requirement. Moreover, the moisture absorption is enhanced by treatment with plaster, which gives a great improvement though the cob partly loses its sweet taste. Other advantages of the corncob pipe is that they do not need to be broken in.

Apart from the use quality pipe the appearance of the cob corn plays an important role. Although the material shows simplicity and limited lifetime, the exclusivity of the model adds to its fame. Though cob corns often have a similar model as wood or meerschaum pipes, the look is still very different, especially since the stem meets the bowl not at the bottom but above it. As noted earlier, the corncob pipe became an anti-status article rather than as a luxury item. The idea that the pipe is made of waste material, already mentioned, is emphasized by the rough surface. On the other hand the high bowls and the long thin stems of the oldest examples give the smoker a special cachet. The corncob pipe started as a pipe for the countryside smoker but soon became known worldwide. It is a pipe with a mid-west look, a country thing but the popularity increased rapidly. Alfred Dunhill signalled the corncob at the beginning of the 1920s in London and New York where it was specially praised among the educated and more affluent smokers.

Because of the positive characteristics it is not surprising that many famous smokers preferred to smoke a corncob, not only by the taste, also because of its special appearance. A special fan is General Douglas MacArthur, who as a Missouri son cultivated his image by life-long smoking the pipe from his native country. The same applies to Mark Twain who lived as a child in Missouri. More unexpected is the French Marshal Foch and much later one of the mayors of New York, La Guardia, was also an avid smoker of corncob pipes. Factory manager Otto senior had a good eye for the publicity of the pipe, a man like MacArthur received periodically a series of new corncobs, even during wartime serving in the Pacific. Some people claim that even Popeye the Sailor man smoked a corncob, which is very well possible with the pipe stem halfway the bowl.

The corncob pipe was available on the Dutch market from the beginning. This is proven by the findings of cast lead pipe bowl bottoms on archaeological sites. This typical Dutch addition secures a longer lifetime of the pipe. As soon as the pipe started leaking at the bottom, some liquid lead was poured into the bowl which solved the problem. A smoker wanted to keep his loved, well-smoked pipe that had a wonderful depth of flavour, even though the lead counteract its weight. Of course this happened at a time when lead was not yet considered to have negative health effects . Whether the sale of cob corns to the Netherlands, where this pipe was widely known, originated in the Dutch roots of the factory, is unclear. Probably not, because publicity printed on the pasteboard was always in English. For the Dutch the smoking of a corncob was probably a welcome change from the clay pipe, especially at a time when the pipe of briar wood was still far too expensive for most of the people.

Today the factory in Missouri is still active. After three generations the Otto family was replaced by a three-headed management of Michael Lechtenberg, Robert Moore and Larry Horton. In accordance to present day practice the production has been further mechanized and simultaneously the number of models drastically reduced to guarantee efficient manufacturability at low price. Almost anything can now be done mechanically. However, the sales price has dramatically risen. In 1948 the consumer could buy a set of three pipes sent home for only a dollar (Fig. 14), thereafter the price continuously increased (Figs. 15, 16). In 1960 a pipe is priced between 25 cents and $ 3.50; shortly before the year 2000 the cost varied from $ 2.20 for the simplest products to twenty dollars for the most expensive examples. In 2008, despite of the continuing mechanisation the price was again higher, the corncob were priced between 4 and 28 dollars.

Moreover, it is worth to mention that the factory for cob corn pipes is not the only one in the world. In the same city of Missouri two competing factories were located, which both are defunct now. In other places in America the corncob pipe production was also started, though no production could compete with the factory founded by Tibbe. For instance in the catalogue of the Akron Smoking Pipe Company in Ohio of 1895 the corncob figured, being produced next to its standard clay tobacco pipes (note 4). In addition to these American examples some Canadian pipes exist of which the most common originating from Huntingdon in the state of Quebec, Canada (Fig. 10).

In conclusion

In 1965 the town of Missouri was elected for the World Championships for pipe smoking. The participant Frank Frankenberg from St. Louis won the race and became world champion in slow smoking. Not coincidentally he smoked from a local pipe, worth only 59 cents. Frankenberg kept his 3.3 grams of Burley tobacco lit for an hour, 33 minutes and 23 seconds (note 5). At the moment that his pipe went out, the bowl fell of the stem, a perfect example of the limited life time of the corncob pipe.

Forty years after this event the corncob pipe still is one of those pipes with nostalgic value such as the Dutch mystery pipe and the traditional clay pipe. Although the sale continues, the use of the corncob is reduced to an experience product. As a serious pipe smoker you want to experience the taste of the cob corn once in your life, to return immediately afterwards to the familiar briar pipe.

© D.H. Duco, Pijpenkabinet Foundation, Amsterdam - the Netherlands, 2008.

Illustrations

- Portrait of Henry Tibbe (Enschede, the Netherlands 1819-Washington, Missouri 1897), wood worker and manufacturer.From: Pfeife und Feuerzeug, 1969, No. 2.

- The factory of Henry Tibbe in Washington, Missouri where the mass production of cob corn pipes was established.

From: Pfeife und Feuerzeug, 1969, No. 2. - Tobacco pipe made from corncob with high narrow light conical bowl, flat bottom, stem on one third of the bowl. Missouri, Washington, 1890-1920.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 18.155a - Tobacco pipe made from corncob with high slightly bulbous narrow bowl, flat bottom, stem from reed on one third of the bowl. Missouri, Washington, 1890-1920.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 18.155b - Tobacco pipe made from corncob with high cylindrical bowl, round bottom, the stem on one third of the bottom, made from thin reed with s-shape with two knots, the third knot is the mouthpiece. The bowl treated with plaster and lacquered on the outside. Missouri, Washington, 1950-1960.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 19.012 - Tobacco pipe made from corncob, shape called Washington with cylindrical bowl without any further treatment, lightwood stem with left a text placed in a ribbon "INDIAN SUMMER", transparent yellow tinted mouthpiece. Base of the bow label with "MISSOURI CORNCOBS MO. PIPE INC.". Missouri, Washington, 1970-1980.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk196c - Tobacco pipe made from corncob, shape called Legend, small size with slight barrel shape, the cob no after treatment, wooden stem with print of cob-design, metal ferrule and plastic mouth piece. Missouri, Washington, 1960-1975.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 196b - High slender corncob pipe, shape called Mac with stem on one third of the bottom, outside treated with plaster and transparent varnish, long upward stem in light wood with metal ferrule and yellow tinted transparent curved plastic mouth piece. Missouri, Washington, 1990-1995.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 196d - Tobacco pipe made from corncob with cylindrical bowl and rounded bowl opening, outside with plaster and lacquered, the bowl opening burnt blackish brown. Bottom bowl intaglio stamp filled in with black "MISSOURI ORIGINAL MEERSCHAUM", bamboo stem with black plastic mouthpiece. Missouri, Washington, 1960-1970.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 196e - Tobacco pipe made from corncob with cylindrical bowl and flat bottom, inserted on the side a straight wooden stem. The cob polished after plaster treatment, bowl label in green with "SUNDAY COB PIPE, HUNTINGDON QUEBEC, CANADA". Black plastic mouthpiece with flattened end. Canada, Huntingdon, 1960-1975.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 196a - Cherry wood pipe from the assortment of Buescher, here styled after the shape of a corncob pipe, at the bottom marked with a label of Buesscher, the stem contains a paper filter in plastic cover. Missouri, Washington, 1960-1970.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet collections Pk 196f - Advertisement for Buescher's corncob pipes, Pfeife und Feuerzeug, 1969, No. 11.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet documentation - Advertisement for corncob pipes showing a display card for a dozen of corncob pipes, from Tobacco, July 1965.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet documentation - Two advertisements from the sales catalogue of a post order business showing the standard corncob and the Mac. New York, Wally Frank, 1948.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet documentation - Advertisement for the standard corncob pipe in a sales catalogue. New York, Wally Frank, c. 1977.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet documentation - Letter from the factory on the forthcoming price changes. Missouri, Washington, December 1996.

Amsterdam, Pijpenkabinet documentation

1. Anonymous, 'Zur Geschichte der Maiskolben-Pfeife', Pfeife und Feuerzeug, 1969, No. 2, p 10.

Notes

2. 'No Shortage of corn cobs', Tobacco, July 1965, p 51. Sets the beginning in 1872, the factory Tibbe would have been founded in 1869.

3. Carl Ehwa, The Book of Pipes & Tobacco, New York, 1974, opposite p 60.

4. Alfred Dunhill, The Pipe Book, London, 1969, p 193.

5. Byron Sudbury, 'An Illustrated 1895 catalogue of the Akron Smoking Pipe Co. ', Historic Clay Tobacco Pipe Studies, 1986, Vol. 3, p 31.

6. Paul Terstraeten, 'Steek ´ns op', Nieuwsblad voor pijprokers (Newspaper for pipe smokers), VI-1, p 2.