Vincents passion for pipe smoking

Author:

Benedict Goes

Original Title:

Vincents passie voor pijproken

Publication Year:

2015

Publisher:

Amsterdam Pipe Museum (Stichting Pijpenkabinet)

The old fashioned clay pipe

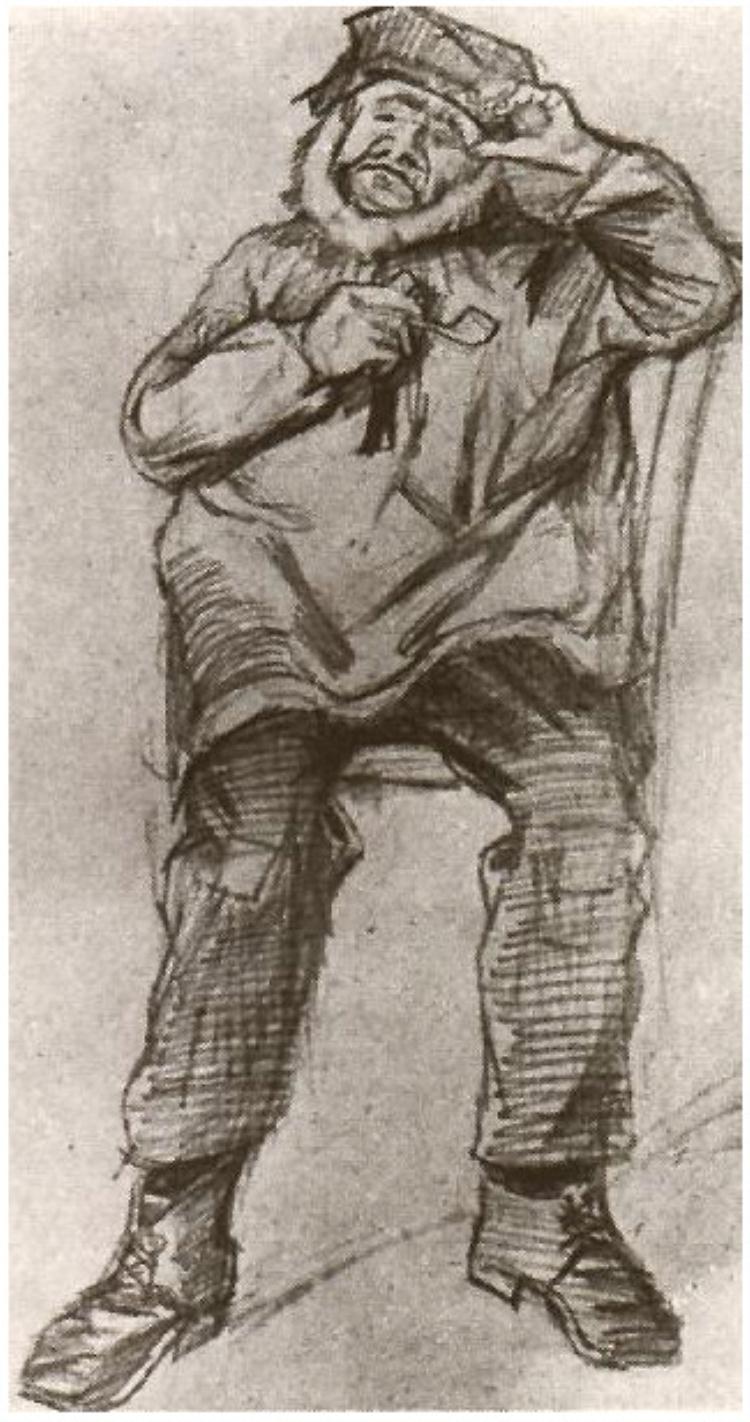

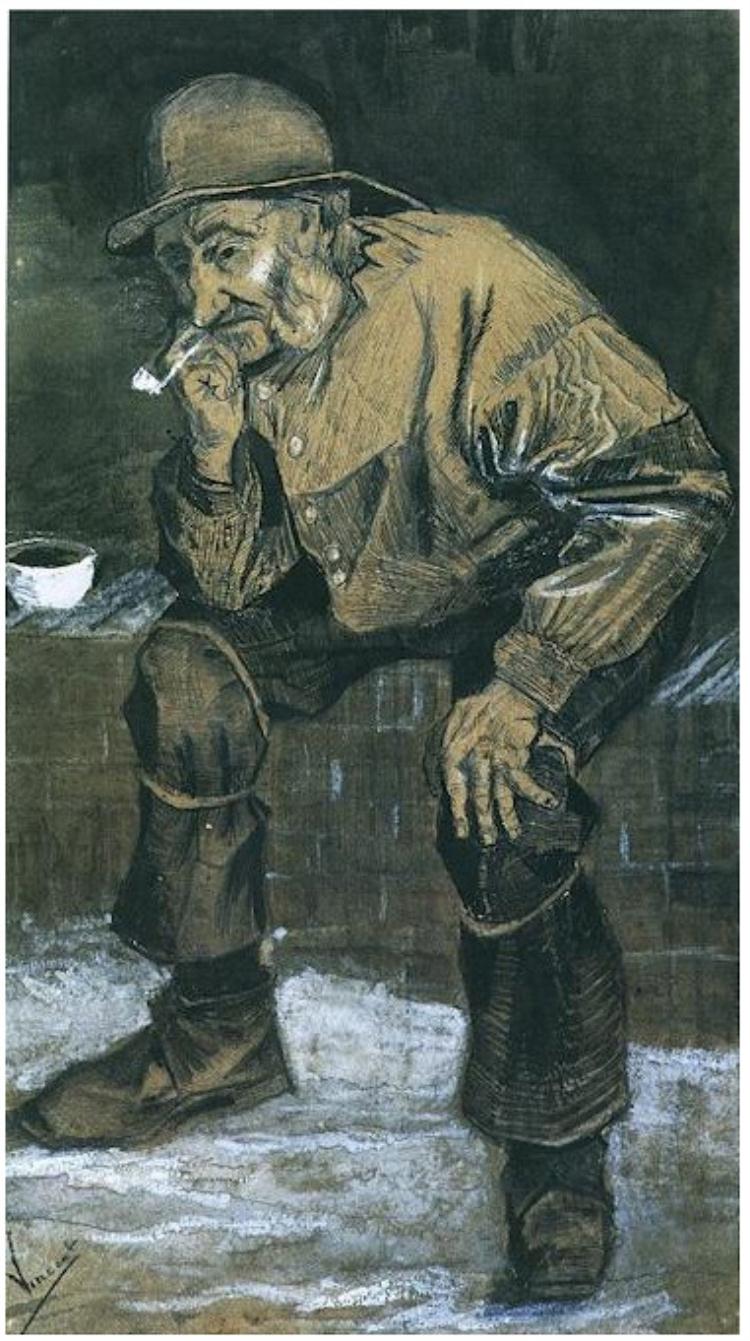

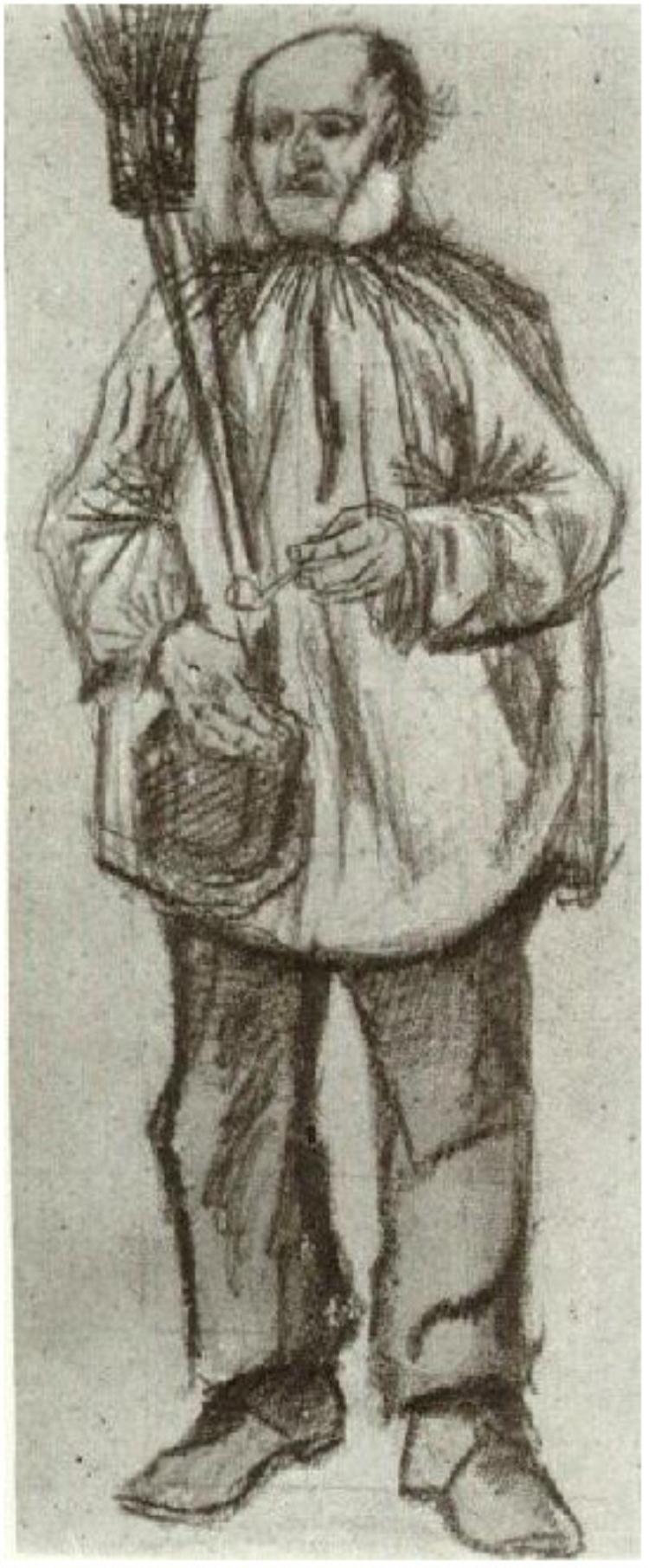

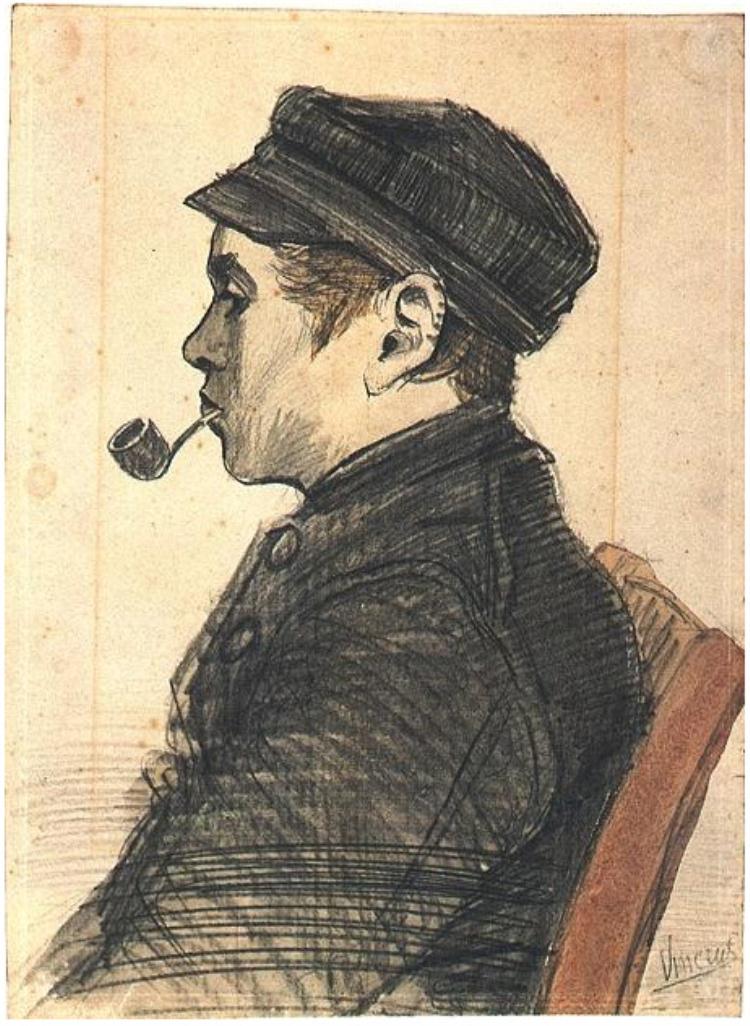

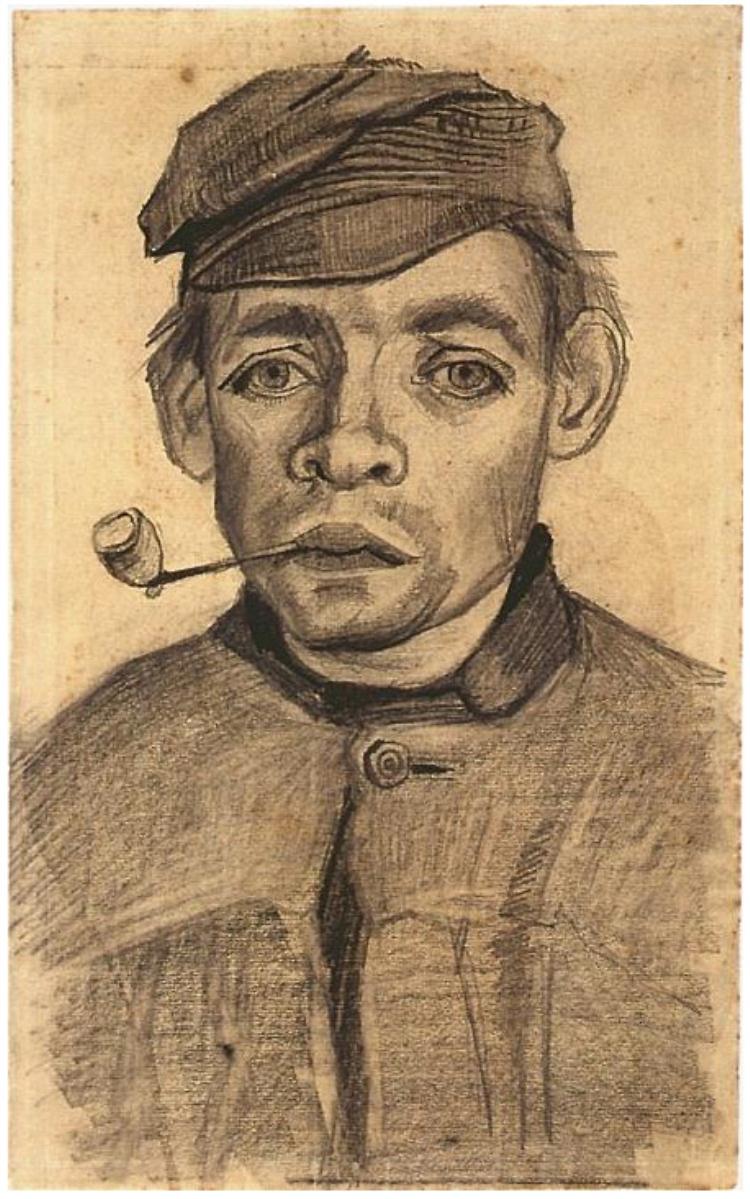

From Vincent's drawings we learn which pipes were smoked in his circles. He practices his art of drawing mainly by capturing the simplicity and poverty of farm life so characteristic of the countryside in the nineteenth century. Fishermen (Fig. 9, 10) and other professions (Fig. 11) were also a popular theme for him, people drawn from life and therefore often including their favourite tobacco pipe. There are countless examples from the years 1883-1885 that Vincent made in Nuenen. He regularly draws the portraits of farm boys and servants, together with their pipe (Fig. 12). Without exception these smokers use simple clay pipes, the well-known cutties. Sometimes you can see from the drawing that the pipe bowl is half white half brown (Fig. 13). This means that the pipe has been smoked for months, so that the white clay gradually became brown at the lower half from the tobacco juices (Fig. 14). It is understandable that the farmers smoked the pipes as long as possible, even if a piece of the stem broke off. This pattern not only came from economy, every smoker knew that a long-smoked pipe tasted better and therefore gave greater pleasure.

Few drawings from that period show the clay pipe with its original stem length. An exception is a pencil drawing made by Vincent in December 1882 of a man with an eye wound (Fig. 15). He writes about this to Theo (letter 297, December 1882):

A second drawing, a head of an injured person with a cloth around his head. The model I used really had a wound in the head and a bandage on the left eye. Just like the head of a soldier of the old guard on his way back from Russia.

The tobacco pipe contrasts so beautifully because Vincent made the drawing even more black with black lithographic chalk. As a matter of fact, not only was the man seventy years old, his pipe was an old-fashioned species as well that had survived time (Fig. 16). The drawing proves that smokers still used the clay pipe at the time.

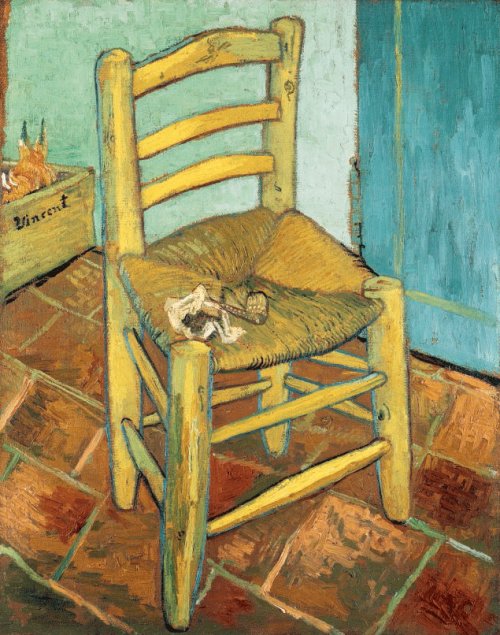

Vincent's chair

One of Vincent van Gogh's most famous paintings is his chair with pipe. He made this work as a counterpart to a painting of the chair of fellow artist Paul Gauguin, for whom he had arranged a guest room in the famous, so-called yellow house (Fig. 17). Gauguin used a rather luxurious chair with armrests, placed on a warm woollen cloth. On the seat is a sconce with a burning candle. For his own chair, Van Gogh chooses a simple wooden chair on a tile floor (Fig. 18). Almost self-evident, but at the same time to show the status difference with his friend Gauguin, Vincent paints a tobacco pipe and a piece of paper with tobacco as a mini-still life on the chair seat.

Vincent describes the painting to Theo (letter 736, January 1889) when he was just released from the hospital in Arles after the incident with his cut off ear:

Today I was working on a pendant - of Gauguin's chair, my own empty chair, a blank wooden chair with a pipe and a packet of tobacco.

Some time later Theo confirms from Paris that he has received a series of paintings by Vincent, including the chair with pipe. The latter suits him very well and Theo writes that from Paris (letter 774, May 1889):

A few days ago, I received your important sending, including great things. Everything arrived well and undamaged. I think the portrait of Roulin, the starry night, the sunflowers and the chair with pipe and tobacco are the best so far.

Even today, Van Gogh's chair is one of his most beloved works. In addition to its artistic quality, this painting is a fine illustration of Vincent's love for pipe and tobacco. Painted in Arles it is not surprising that the tobacco pipe is no longer a Dutch clay pipe. It was exchanged for a more mundane French clay pipe with a wider bowl and a shorter, slightly curved stem. Around the bowl, the pipe is decorated with pearls of enamel, a characteristic of the French pipe makers of the time. When the pipe turned darker due to smoking, the dots stood out like a kind of mille-point enamel against the background. To what extend those pipes were consumable objects, is proven by the fact that a similar one has not yet been found back. Hence two copies are shown here. The first example shows the model of such a clay pipe, but with a decoration in relief, which is also heightened with enamel paint (Fig. 19). The second pipe has a different shape, but shows the same white enamel dots that stand out vigorously against the dark-tinted surface (Fig. 20) as can be seen on the painted chair.

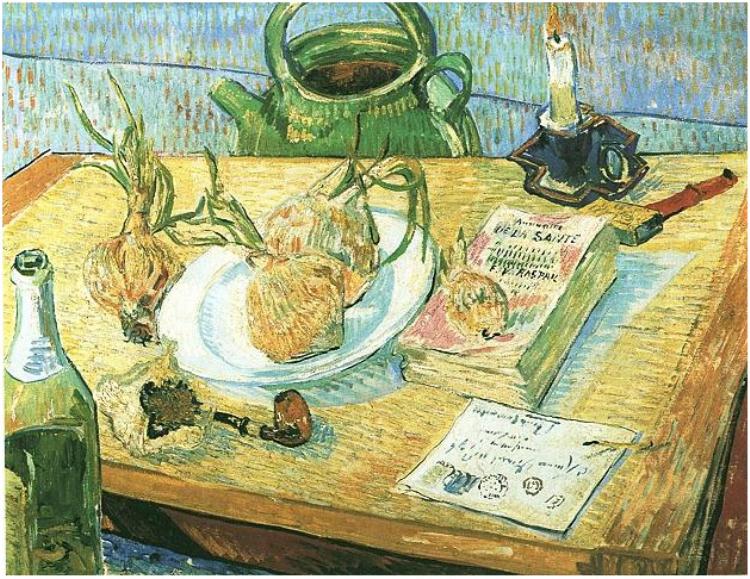

Vincent's still life with straw hat (Fig. 21) again depicts a short clay pipe that has been found as an exact copy (Fig. 22). This elegant clay pipe with a smooth line from bowl opening to mouthpiece is covered with a calcine lacquer. This yellow lacquer makes the pipe remotely resemble smoked meerschaum, which has a beautiful yellow sheen but is much more expensive as material. Hence, these types of tobacco pipes were simulated in the much cheaper clay.

A tobacco pipe appears in another still life (Fig. 23). Again it is a short pipe, now with a separate mouthpiece. Smoking for years caused the pipe to become dark brown. Unfortunately, we cannot find an exact counterpart for this pipe either. It is proof how few consumable daily implements from the past have been preserved.

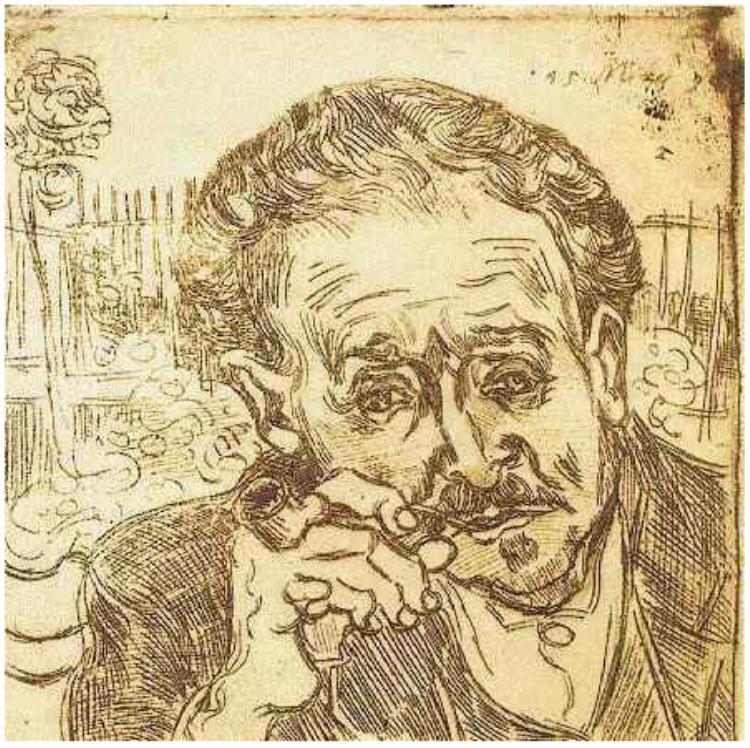

Portrait of Doctor Gachet

A year later, brother Theo van Gogh was delighted again by the etching Vincent made with the portrait of doctor Gachet with pipe (Fig. 24). It is an etching with a very present portrait of the doctor looking intensively at the viewer. Theo applauds this portrait in his letter from Paris (letter 890, June 1890):

I have to tell you something about your etching: I really like this drawing; Bock also liked it.

Vincent had sent a proof of the same portrait to his friend Paul Gauguin, who later wrote back from Le Pouldu that he was also happy with the etching. (letter 892, June 1890, translated)

My dear Vincent, coming back from a short trip, I found your letter and proof of the etching.

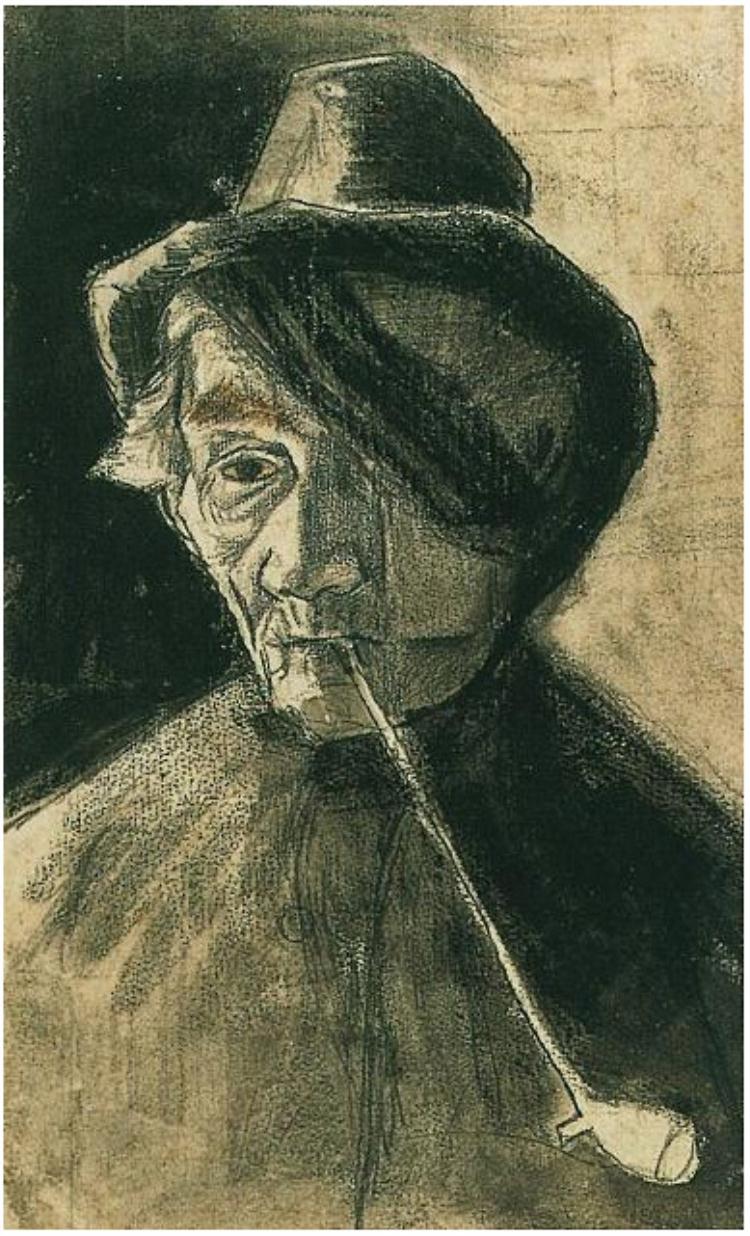

The doctor who looks at the viewer so penetratingly smokes a clay pipe with a so-called cuff. The pipe bowl has a short stem ending in a sturdy stub (Fig. 25). A stem of bamboo, wood or reed was inserted into it. It is a simple pipe, too simple for a doctor. On the other hand, it was the type of pipe that was very popular in France for decades. The French pipe factories have manufactured and sold millions of these cuff pipes, in the most diverse shapes. In addition to pipe bowls sometimes even with portraits, most copies were of course simply unadorned, as with Dr. Gachet. The two-tone etching makes it impossible to see the colour of the pipe. Cuffed bowls were not only supplied in white clay at that time, red and black baked versions were also popular. In general, red, brown or black pipes were smoked more often in the southern France.

Another portrait by Vincent van Gogh shows a unknown man with a pipe (Fig. 26). Here again it is not clear what kind of tobacco pipe is depicted. It appears to be a pipe made of meerschaum rather than clay and it can clearly be seen that a spark catcher has been placed on the pipe bowl, a cap to prevent sparks from falling out of the pipe causing burning holes in the clothing. The relationship between the pipe bowl and stem makes this possibly a meerschaum pipe, mounted on a thin duck leg stem (Fig. 27). A short-lived fashion from those years among the more artistic smokers.